The unusual story of Moses does fit neatly into the deeply obscured story of Hatshepsut. Moses must have fled after the death of his protector and then he returned years later in order to extract his familie's tribe. This led to a serious upheaval in Egypt for which he was certainly blamed.. Yet he also was then an old man already.

Regardless this sets the exodus at 1440 BC., This is an important date to have and any error should be small. I also have 1159 BC for the end of the Atlantean world as well and 1179 BC or the end of Troy in the Baltic. Thera happened around two centuries before the exodus then.

That also suggests that the Jews entered Israel around 1400 BC and had two and one half centuries to establish themselves there before their conflict with the Philistines began. This was clearly a powerful echo of the Atlantean end in 1159 BC.

Has the Biblical Moses Been Identified in Secular Egyptian Records?

8 August, 2019 - 18:59

Annette DuckworthRegardless this sets the exodus at 1440 BC., This is an important date to have and any error should be small. I also have 1159 BC for the end of the Atlantean world as well and 1179 BC or the end of Troy in the Baltic. Thera happened around two centuries before the exodus then.

That also suggests that the Jews entered Israel around 1400 BC and had two and one half centuries to establish themselves there before their conflict with the Philistines began. This was clearly a powerful echo of the Atlantean end in 1159 BC.

Has the Biblical Moses Been Identified in Secular Egyptian Records?

https://www.ancient-origins.net/history-famous-people/moses-0012411

Moses

was a prophet and a leader according to Abrahamic religions, but many

scholars view him as a legendary figure rather than a real historic

person. They do concede that a Moses-like figure could have existed in

history, so is it possible to track this person down through historic

records? It is the view of this writer that this is very possible and

that in fact the Moses figure can be traced as that of the primary

confidant of none other than Egyptian pharaoh Hatshepsut. The trail

begins with Th Exodus.

The Exodus and Moses Birth

What is the date of the Exodus ? To find Moses in the Egyptian records, the first requirement is to fix the date of the Exodus of the Hebrews from Egypt.

If we use the Bible as our primary source, we know that this occurred during the ‘ New Kingdom ’ period of Egypt, when the powerful Egyptian families of the south reasserted themselves and drove out the Hyksos invaders , who had been entrenched in the power centers of northern Egypt for over 100 years.

The Hyksos’ stay in Egypt is known in history as the ‘Second

Intermediate Period’. However, there is a difference of opinion among

biblical scholars as to when, during the New Kingdom, the Exodus

occurred. So, can we find anything to help us pin it down?

If one accepts the biblical dating of Solomon’s time ,

we know that he started building his famous temple in 960 BC, and the

text of 1 Kings 6 v1 states that this was 480 years since the Exodus .

Thus, we can fix a date for the Exodus of 1440 BC, when Moses was 80 years old. This would mean that he was born around 1520 BC and is an adult in the court between 1500 and 1480 BC.

Where Does the Name Moses Come From?

1500 – 1480 BC is the time of the pharaoh Queen Hatshepsut, and she had a close confidant, described by the well-known Egyptologist Joyce Tyldesley in her book on Hatshepsut, as the ‘Greatest of the Great’.

The father of Hatshepsut was Thutmose l ,

and his name means ‘son of Thoth’, the god of wisdom, ‘mose’ meaning

‘son’. This is a common use of the word ‘mose’ as in ‘Ra meeses’, son of

the sun god Ra, etc.

The biblical text tells us that it was the pharaoh’s daughter who

named Moses. Exodus 2 v 10 states that, “she called him Moses because

she said, ‘I drew him out of the water’”.

But we will not find a Prince Moses in the court in Egypt because another bible reference, Hebrews 11 v 24, states that “ Moses, when he had grown up, refused to be known as the son of Pharaoh’s daughter”.

Instead, we find that the close confidant of the queen is a man called ‘ Senenmut’.

This appears to be a unique name, and one of its meanings is ‘mother’s

brother’. Hatshepsut was born in the early 1530s, so they were close in

age, so such a name makes sense.

Why Would the Royal Heiress Adopt a Slave Child?

If Hatshepsut is the woman who rescued and adopted Moses, what would

make a woman of such high standing adopt a slave child? After her

mother, Hatshepsut was the highest woman in the land, and such a woman

would not consider saving the life of a slave child, let alone adopt him

as her son.

But when we look at the past, it is hard for us to

remember that the people we are observing are just like us. They have

thoughts and feelings like us, and Hatshepsut, at the time she found the

abandoned baby in the basket, was a little girl, with the instincts to

protect the helpless that we see so often in children. The text of

Exodus 2 v 6 says “she saw the child, he was crying, and she took pity

on him”.

Hatshepsut knew that he was a Hebrew child, as the rest of the verse

tells us. But she was too young to look ahead and understand the

enormity of her action. Almost immediately she must have formed an

attachment to him, and as he grew the attachment grew, and her loyalty

to him would alter the course of her life.

So, What Do We Know of Hatshepsut?

We know that Hatshepsut married her brother, Thutmose II, becoming

his ‘Great Royal Wife’, his principal queen. She bears him two daughters

but no sons and, following his death after a reign of only 13 years,

his son by a harem woman is made the pharaoh, becoming Thutmose III .

This new pharaoh is an infant and Hatshepsut is made regent. She is

effectively the ruler of the land, holding all the power already, and so

it seems odd to Egyptologists that after just two years she makes

herself pharaoh.

Did she have ambitions to put her adopted son on the throne? This she

could do if she were pharaoh, but not if she were only regent. She

reigns as the senior pharaoh, jointly with Thutmose III for 22

successful years, until her death.

She rules the country well. She sets up trading expeditions with the

lands south of Egypt. She keeps a firm grip on Nubia, Egypt’s southern

neighbor from which vast resources are acquired, including gold, cattle,

slaves, and soldiers. She carries out extensive building works, both in

Waset, the ancient name for Luxor, and around the country.

Life-sized statue of Hatshepsut. She is shown wearing the nemes-headcloth and shendyt-kilt, which are both traditional for an Egyptian king. The statue is more feminine, given the body structure. (Pharos / Public Domain )

She extends the Temple of Amun in Waset, erecting 4 huge obelisks in

his honor, two of which are still there, one still standing. It bears

engravings as clear as they were when it was erected 3,500 years ago,

reading – “Raised for the glory my father Amun that I may be given

life”. She builds a magnificent mortuary temple for herself ,

where the gods are honored, known as the Temple of Deir el Bahri, which

still stands and is visited by thousands of tourists every year.

What Happened to Hatshepsut’s Memory After Her Death?

Hatshepsut ruled her country well and was buried honorably, probably

with her father Thutmose l in tomb KV 20, a tomb she had built for a

double burial.

After the death of his stepmother, Thutmose III continued his long

reign of over 50 years, spending much of that time campaigning in the

Levant, defeating the power of the Hittites to the northwest and the

Mittani to the northeast and bringing the wealthy city states of Canaan

firmly under Egyptian control. He is known as the ‘Napoleon of Egypt’

for his success as a military man.

But 30 years after her death, all records of Hatshepsut

came under attack. Her statues were removed from the temples, smashed

and buried in a pit, and her reliefs were excised from the walls of the

temples. In subsequent years, Hatshepsut’s name was omitted from the King Lists ,

a thing done to no other pharaoh except the great heretic pharaoh

Akenaten but not to the one previous female pharaoh Sobekneferu who

reigned briefly at the end of the 12th Dynasty.

3

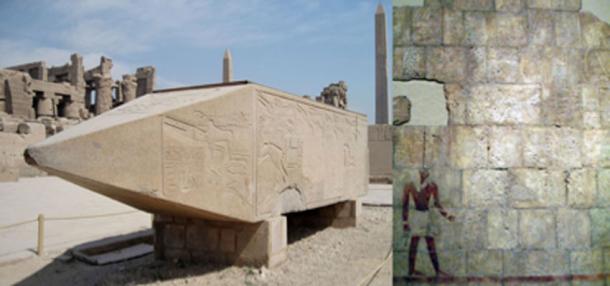

On Left - A fallen obelisk of Hatshepsut. On Right - The image of Hatshepsut has been deliberately chipped away and removed. ( CC BY-SA 3.0 / CC BY-SA 3.0 )3

On Left - A fallen obelisk of Hatshepsut. On Right - The image of Hatshepsut has been deliberately chipped away and removed. ( CC BY-SA 3.0 / CC BY-SA 3.0 )3

Removing all record of Hatshepsut’s name was intended, by the

Egyptians, as the ultimate punishment, known as ‘damnatio memoriae’. All

records of a person removed from history as if they had never lived

resulted in the death of their soul for eternity. This effectively

removed Hatshepsut from Egyptian history until all memory of her and why

she had been so hated was lost.

She was forgotten for over 1,000 years, until vague references to her

were found by the priest Manetho in 300 BC when he was asked by the

Greeks in power at that time to search out and list the pharaohs of

Egyptian history. He found references to a female pharaoh called

Amensis, who was identified by later Egyptologists as Hatshepsut, and

recorded her as the fifth pharaoh of the New Kingdom Dynasty, but

nothing more was known of her.

It was thought that Hatshepsut’s mummy had been lost, but it has

recently been identified lying abandoned in the tomb of her royal nurse

Sitre, tomb KV 60. It was identified by a tooth fragment known to belong

to Hatshepsut, and the mummy appeared to have been left without

ceremony, perhaps in haste to hide it from those who would have

destroyed it. The Egyptians believed that the preservation of the body

was essential to survival in the afterlife, hence the lengths they went

to, to preserve them. It was the ultimate punishment to destroy a

person’s body.

So, Who Would Have Tried to Remove Hatshepsut From History?

The action against Hatshepsut’s (and Senemut’s) memory occurs either

late in the reign of Thutmose III, when his son Amenhotep II was sharing

the throne, or after Thutmose’s death, when Amenhotep II was reigning alone. It seems therefore to be Amenhotep II who is responsible for this destruction.

He would be at the correct time to see the return of Moses demanding

the release of the Hebrew slaves. The story of the Exodus describes

great hardship for Egypt, and one can understand Amenhotep’s fury

against both Hatshepsut and Senenmut and wishing to destroy their

memory. Being wiped out of history for the Egyptians was tantamount to

eternal damnation.

When Were Hatshepsut’s Statues Discovered and What Did They Reveal?

During the 1800s, wealthy gentlemen such as James Breasted went to

Egypt specifically with the hope of finding evidence to prove the biblical record . These men effectively established the science of Egyptology.

But at that time, the statues of Hatshepsut still lay buried in the

pit where they were thrown 30 years after her death. They remained there

undiscovered until found by Herbert Winlock an American Egyptologist

employed by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in Boston, United States in

1927, by which time the world at large was no longer interested in

trying to prove the Bible.

But not only was a hoard of statues of

Hatshepsut discovered just east of the first court of her mortuary

temple at Deir el Bahri. Another pit was found, containing over 20 hard

stone statues of Senenmut, a huge number for a non-royal. In fact, to

date, 26 hard stone statues of Senenmut have been identified which

causes Egyptologists to wonder what was it about this man that he was

given such status.

Kneeling statue of Senenmut, Chief Steward of Queen Hatshepsut. (FA2010 / Public Domain )

What Do We Know About Senenmut?

The first thing to confront us when looking at the records of

Senenmut are the many beautiful statues of him as a young lad holding

Hatshepsut’s elder daughter, the Princess Neferure . She is there wrapped in his cloak as a baby as he sits on the ground.

He is holding her in his arms the way a woman would hold a child. In

some examples he sits on a chair holding her on his lap. Some are of him

standing holding Neferure

as a toddler, but altogether they show a level of intimacy between the

two of them, as we would have in photos taken of our children together.over?

He is said to be the tutor to Neferure, but statues of a royal child

being held like this had never been made before this date. And this is

breaking protocol because a non-royal is not allowed to touch a royal

child in this way.

And we know that Senenmut is not royal because he names his parents

in one of his tombs, and they have no titles at all, showing that they

are of humble origin. But the extraordinary thing about Senenmut is that

he is treated as a royal.

He has two beautiful tombs built for himself, one, TT 353

has the oldest known star chart, a work of great expertise, on the

ceiling. And this tomb is actually within the sacred precinct of

Hatshepsut’s mortuary temple. This is a sacred space and to have

Senenmut’s tomb in such a place, sacred in itself, but also the personal

space of the pharaoh, shows a degree of closeness between them that is

shocking, unless there is an explanation for it.

The other tomb TT 71 has decorations described by the Egyptologist Peter Dorman in the book ‘ Hatshepsut from Queen to Pharaoh’ ,

page 131 as being clearly done “by artists from the royal ateliers”.

Dorman also dismisses the suggestion that Senenmut may have been

Hatshepsut’s lover.

In this tomb TT 71, a sarcophagus belonging to

Senenmut was found. It is made of quartzite, a material only allowed to

be used by the royals.

We know that Moses neither dies nor is buried in Egypt. And Senenmut

is not buried in either of his tombs but disappears from Egyptian

records.

Besides the statues of Senenmut holding the infant princess, there

are many statues made of him making offerings to the gods. These statues

were made to stand in the presence of the gods, and again, it is not

permitted for a non-royal to enter the presence of the gods; having your

statue there was the equivalent of you being there in person.

Here again he is treated as a royal. And all these statues are of a

very young man, so it must be Hatshepsut who ordered these statues to be

made. To be in the presence of the gods was a very favored position,

because you would receive the continual blessings of the gods.

We also find a number of reliefs carved in the most sacred space of

all in the Deir el Bahri Temple, in the sanctuary of Amun itself. One is

even carved in the back wall of the sanctuary, where the ceremonial boat

which carried the idol of Amun was placed overnight before its return

journey to Waset. For the images of a common citizen to be placed in

such a sacred space, breaks every rule in the book, but Hatshepsut must

have done this, and done it because Senenmut was the son she had

adopted, and she was ambitious for him to rise high in Egypt.

During the course of his years at the court of Hatshepsut, Senenmut

is acknowledged by experts in Egyptology, to have held many of the

highest titles in the land, showing that he truly was the ‘Greatest of

the Great’, in Hatshepsut’s court.

Senemut’s high standing in the court during the reign of Hatshepsut,

coupled with him being wiped from the Egyptian historical narrative, and

the correlation between the biblical and Egyptian dating, would suggest

therefore that he was the person we know from the Bible as Moses.

Having discovered the story of Hatshepsut and Senenmut, I decided to

present it as an historical novel. It was published in October 2018 by

Mirador. It is called ‘ The King and her children’ and is available from Waterstones and Amazon.

By A.R. Duckworth

No comments:

Post a Comment