:focal(2808x1872:2809x1873)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/e0/d3/e0d351a9-df01-4f90-bae5-ae224ffbe408/gettyimages-112766116.jpg)

This is a damn good question. The idea of a religion, rather than a local cult evolved with Baal worship and also the Greek Pasnthean as well and did so almost inside historic times. Judeism was the local cult then sponsered by Herod the Great into the Roman Empire and extended Alexandrian proto empire. Both had a common language facilitating this.

At the same time, other cults were also fomented. This is why Christianity expanded so fast on these already established networks that themselves had largely formed almost in living memory. It all turned out to be a sucessful enterprise able to thrive locally anywhere and support other communnities as well. Not least independent of any local strongman.

So religions as such arose or evolved as part of the growth of empires and ultimately found themselves as a form of imperial glue.

Judeism itself does have a long cult history but centered upon the Temple and the Ark of the Covenant but was very much an impressive tribal cult. It reformulated as a religion after expulsion from the holy land and paralel to Christianity. The scriptures themselve were largely written down after the retyurn from Babylon. Substancial portions certainly came from earlier unknown texts,.

In this way the scriptures were secured and then promulgated by the Chritians globally.

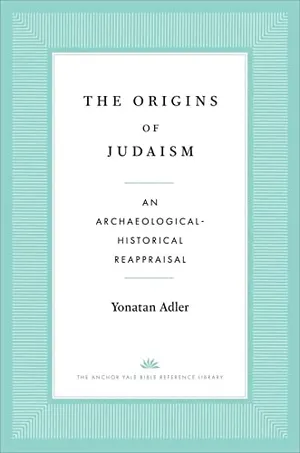

Is Judaism a Younger Religion Than Previously Thought?

A new book by an Israeli archaeologist makes the stunning claim that common Jewish practices emerged only a century or so before Jesus

CorrespondentNovember 15, 2022

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/is-judaism-a-younger-religion-than-previously-thought-180981118/

If Yonatan Adler's theory proves correct, then Judaism is, at best, Christianity’s elder sibling and a younger cousin to the religions of ancient Greece and Rome. Photo by Uriel Sinai / Getty Images

It’s the grandparent of Islam and Christianity and one of the world’s oldest surviving religions, by some counts dating back nearly 4,000 years. This, at least, has long been a common view of Judaism. But now an Israeli archaeologist is challenging those long-held assumptions.

Based on 15 years of studying textual and archaeological evidence, Yonatan Adler of Ariel University, in the West Bank, concludes that ordinary Judeans didn’t consistently celebrate Passover, hold the Sabbath sacred or practice other traditional forms of Jewish ritual until a century or so before the birth of Jesus. If his theory proves correct, then Judaism is, at best, Christianity’s elder sibling and a younger cousin to the religions of ancient Greece and Rome.

Groundbreaking research that utilizes archaeological discoveries and ancient texts to revolutionize our understanding of the beginnings of JudaismBUY

Report an ad

Adler lays out his case in The Origins of Judaism, a new book published Tuesday by Yale University Press. He argues that standard Jewish practices, from ritual bathing to avoiding representational images of humans and animals, didn’t come into widespread use until around 100 B.C.E.

That date is some 900 years after the Israelites settled in Jerusalem, which became the center of a region later known as Judea. It’s also several centuries after most scholars believe that Judean scribes in Jerusalem put together the books of the Hebrew Bible—a document long seen as the basis of Judaism. According to Adler, while some Judeans may have known about the religion’s rules and prohibitions, this “does not imply that anybody was necessarily putting [them] into practice.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/1f/f3/1ff329d6-bc9a-4468-9e53-18cf2f886236/2560px-part_of_dead_sea_scroll_28a_from_qumran_cave_1_the_jordan_museum_in_amman.jpeg)

Fragments from the Dead Sea Scrolls, ancient Jewish and Hebrew religious manuscripts recovered from the Qumran Caves in the mid-1940s Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin via Wikimedia Commons under CC BY-SA 4.0

Adler examined artifacts from dozens of excavations in the Levant, as well as ancient texts, including the Bible, to determine how people behaved in the centuries before the Romans destroyed Jerusalem in 70 C.E. His analysis has won initial praise from some Near Eastern archaeologists and textual scholars who have examined the arguments laid out in the book. “He makes a good case that is certainly worth considering seriously,” says Jodi Magness, an archaeologist at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill with extensive experience excavating in Israel. Harald Samuel, a classical Hebrew expert at the University of Oxford in England, says, “Adler’s work is absolutely solid.”

The new findings challenge conventional wisdom that assumes Jewish practices evolved in the same era as the Hebrew Bible was written—a view that Samuel argues will be hard to alter. They are also likely to raise broader questions of what constitutes Judaism and religion more generally.

Ritual baths, chalk cups and graven images

The Hebrew Bible contains a number of provisions required to maintain ritual purity, which eventually took the form of bathing in distinctive immersion pools known as mikvahs. As Jesus’s disciple Mark says in the biblical book of the same name, Jews returning from the marketplace “do not eat unless they wash.” In the past century, excavators have identified at least 700 of these small baths scattered across ancient Judea. According to Adler, the vast majority of the pools date to the first century B.C.E. and the first century C.E.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/55/b4/55b444ba-792b-41cf-ae5c-a60486f39bd5/adlerfig04.jpg)

Immersion pool filled with groundwater at Magdala Aviad Amitai

Based on a comprehensive analysis of previously discovered vessels, the archaeologist notes that the use of chalk pitchers, bowls and cups for storing food and drink began about the same time. Unlike ceramic pottery, chalk was thought to be impermeable to spiritual impurities, and it became highly favored by many Judean households in the first century B.C.E. The porous and dusty material is more difficult to manufacture than ceramics, and it was not previously used by Judeans or other peoples in the region.

A strict taboo on graven images, expressed in the Bible’s second commandment, also appears to be a late development. Coins made in Judea during the fourth century B.C.E., when the province was part of the Persian Empire, and then after Alexander the Great conquered the region around 331 B.C.E. often include both the names of Judean officials and images of eagles, bearded men, winged lions and even foreign deities, suggesting they were widely used by Judeans despite the biblical prohibition.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/e5/ed/e5ed8744-6d7a-42d1-99a7-953ae9352a38/g71-5_copy.jpg)

Jug featuring likeness of the Egyptian god Bes Israel Antiquities Authority

Nor was this prohibition strictly adhered to even in the shadow of the Temple Mount, the preeminent Judean sanctuary on Jerusalem’s acropolis. During a recent excavation just south of site, Israeli archaeologists uncovered a host of artifacts featuring likenesses, including an image of the Greek goddess Athena and a jug carved with the face of the Egyptian god Bes; the latter was made from local clay and is therefore not an import. Though these objects may have been owned by non-Judeans, the finds suggest that at least some Jerusalem residents did not abide by the graven images taboo.

Jewish holy days

Biblical law also forbids preparing food, riding and drawing water, among other activities, on what is known as the Sabbath. “We do not know how pervasive Sabbath observance was during early biblical times, and when exactly the observance of the Sabbath took hold among the ancient Israelites,” says Rifat Sonsino, a theologist at Boston College. Adler says he found “no evidence predating the second century B.C.E. which suggests that ordinary people regarded any kind of activities as prohibited on that day.”

Adler cites passages in biblical books to back up his assertion: In Nehemiah, for instance, the titular narrator complains about Judeans blatantly ignoring religious leaders’ strictures regarding the Sabbath. “The masses,” says Adler, “were not heeding their call.” He adds, “If anyone would like to argue that the general populace knew of any kind of Sabbath prohibitions, the burden of evidence lies firmly on his or her shoulders to show that this was the case.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/88/ba/88ba646b-0b3a-4c91-8560-14c14ed5b475/david_roberts-israelitesleavingegypt_1828.jpeg)

David Roberts, Israelites Leaving Egypt, 1828 Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

The same holds true for important Jewish holidays such as Passover, which commemorates the ancient Israelites’ escape from Egyptian servitude as described in the Bible. Adler says there is little sign in non-biblical Judean and foreign texts that this event was celebrated widely—if at all—among common people prior to the second century B.C.E. That clearly had changed dramatically by the time of Jesus, when Passover was described in the Christian Gospels and other contemporary texts as a well-established holiday that drew thousands of pilgrims to Jerusalem.

Another major Jewish holiday is the Sabbath of Sabbaths, a sacred day of fasting and prayer that came to be known as the Day of Atonement, or Yom Kippur. According to the Christian Gospels, says Adler, the commemoration “appears to have been universal” among Judeans by the time of Jesus. But the archaeologist found no earlier texts mentioning the widespread commemoration of this holiday. The same proved true for the Feast of Tabernacles, or Sukkot, which harks back to the sheltering of the Israelites in the desert after their escape from Egypt.

Even the iconic seven-branched menorah seemingly dates to long after the Hebrew Bible was written. “Prior to the mid-first century B.C.E., not a single example has been found of [one] depicted in Judean (or Israelite) art,” notes Adler. Synagogues, meanwhile, only appear in significant numbers in the first century C.E., according to the archeological record.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/fd/e3/fde3c907-4926-4670-b13b-3a2067f2a8d9/adlerfig03.jpg)

Catfish vertebrae from Jerusalem’s Givʿati parking lot Abra Spiciarich

Adler’s study of dietary habits, based on an analysis of animal remains, suggests that Judeans avoided eating pork and fish that lacked scales in the centuries directly preceding Jesus’s birth. This appears to be in line with biblical prohibitions, but the presence of scattered pig and catfish bones indicates such restrictions did not have universal support. Adler says these food taboos could predate biblical prohibitions and be linked to non-religious matters. He points out that pigs require water and other resources that make them more demanding domesticated animals than sheep or goats.

Hasmonean nation-building

Before the middle of the second century B.C.E., Adler believes Judeans were governed by “cultural norms and traditions inherited from the Iron Age”—that is, the centuries immediately after the Israelites arrived in Jerusalem. Veneration of the deity Yahweh was clearly part of this tradition, and there are hints of practices that later became common, such as a Passover meal at Elephantine Island in southern Egypt in 419 B.C.E.

In Adler’s view, the rise of what are today common Jewish practices coincided with Judean independence from Hellenistic control. The homegrown Hasmonean dynasty, formed around 140 B.C.E., began to issue coins devoid of animal and human images. As the archaeologist argues, it was during this era that Judeans became more familiar with scripture and began to abide by its lists of rules on a day-to-day basis as they distanced themselves from their former overlords./https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/34/53/34533b9b-1af1-42f7-a1c1-89c88611d543/hasmonean.jpg) Hasmonean coin CNG Coins via Wikimedia Commons under CC BY-SA 3.0

Hasmonean coin CNG Coins via Wikimedia Commons under CC BY-SA 3.0

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/34/53/34533b9b-1af1-42f7-a1c1-89c88611d543/hasmonean.jpg) Hasmonean coin CNG Coins via Wikimedia Commons under CC BY-SA 3.0

Hasmonean coin CNG Coins via Wikimedia Commons under CC BY-SA 3.0By that time, Adler writes, Judeans were already “deeply embedded in a world dominated by Hellenistic culture”—a Greek-speaking milieu of classical learning, entertainment and a highly developed pantheon of deities. He contends that Judaism could therefore be seen as emerging from “the crucible of Hellenism” rather than from the tents of Abraham or Moses.

That emergence, Adler adds, “was the catalyst for setting the course of much of world history over the past 2,000 years—and probably also for centuries if not millennia to come.”

Gad Barnea, a biblical scholar at Israel’s University of Haifa, speculates that “the most likely trigger” for the process that led to the codification of the Torah was the construction of the Library of Alexandria in the third century B.C.E.—an institution that spread learning and drew Judean scholars. Around that same time, the Hebrew Bible was translated into Greek for the first time, making it accessible to foreigners, as well as Judeans who spoke Greek and Aramaic rather than Hebrew. Barnea argues, however, that widespread Judean adoption of specific religious practices only arrived under the relative autonomy of Hasmonean rule.

Konrad Schmid, a biblical scholar at the University of Zurich in Switzerland, agrees that “before the Hellenistic period,” knowledge of the sacred text “was probably limited to small scribal circles centered in Jerusalem.” He speculates that the Hebrew Bible’s rules could have been conceived not as laws but as “a document depicting an ideal community.” He is unsure, however, if the text remained obscure to most Judeans as late as the second century B.C.E.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/f8/8e/f88e5075-2803-4b0d-9846-5a51b6775a55/jerusalem_8141581890.jpeg)

A menorah at the Western Wall in Jerusalem StateofIsrael via Wikimedia Commons under CC BY-SA 2.0

Barnea calls Adler’s book “important” and agrees that before the Hasmonean era, there seems to be “not a shred of awareness” of “any degree of familiarity” with the Hebrew Bible. But Michael Langlois, a biblical expert at the University of Strasbourg in France who has not yet examined Adler’s research, says Judaism existed “centuries before the common era,” albeit in a different form than today’s Judaism of synagogues and rabbis. He dates the origins of Judaism to before the Babylonian destruction of Jerusalem in 586 B.C.E. The faith, he adds, “slowly evolved throughout centuries to give birth to different forms, including rabbinical Judaism.”

Other experts agree. “I would argue that there are previous forms of Judaism” that existed before Hasmonean times, says Jonathan Stökl, a biblical authority at Leiden University in the Netherlands. Stökl deems Adler’s finds “significant” but suggests that Judeans could have been Jews even if they didn’t precisely follow the guidelines laid out in the Hebrew Bible.

Whether scholars accept Adler’s bold thesis will depend in part on how they define the concept of religion. Samuel suspects that many academics will push back against the idea that widespread adoption of biblical law did not occur until later than previously thought.

“I don’t see that this view, even though obvious to me, could claim to be a majority position in the near future,” he says. “I assume the traditional picture is way too influential.”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/71626022/Vox_November_Highlight_Story_3__Composition_3__Final.0.jpg)