The best take home that is good for everyone is to consciously walk briskly for about twenty minutes every day. This can be obviously fitted into our routines and that will also trigger a reminder as well. It may be your daily trip to a store or your walk from a parking spot to your office. Most of those are typically ten minutes.

It all provides a base of physical activity that encourages the whole body to shift up a notch.

Since I have convinced myself that I am in training to do the Camino, I did a real ten mile walk this past weekend in four hours. Doing that, things become possible. Yet once a week allows ample Restoration. Again twenty minutes is not overkill for a brisk walk..

The Case for Walking

It all provides a base of physical activity that encourages the whole body to shift up a notch.

Since I have convinced myself that I am in training to do the Camino, I did a real ten mile walk this past weekend in four hours. Doing that, things become possible. Yet once a week allows ample Restoration. Again twenty minutes is not overkill for a brisk walk..

The Case for Walking

https://elemental.medium.com/the-case-for-walking-431b82f1eaa9

Some people get a little fanatical about their exercise. Take I-Min Lee. She walks routinely instead of driving, and she runs regularly. Lee wears a step counter and is “a little obsessed” with keeping track. “This makes me understand how the little things we do during the day can add up to quite a large total number of steps,” the 59-year-old says. Lee admits she has more motivation than the average person. “After all,” she says, “would you listen to a researcher who does not practice what she studies?”

Lee is an epidemiologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Massachusetts who focuses on how physical activity can promote health and prevent chronic disease. Her latest study is actually about steps. Specifically: How many, or how few, an older person needs to take on a daily basis to reap significant health perks.

Along with several other studies out this year, the results reveal the incredible power of simply doing what humans have done since we stopped swinging from trees. And Lee’s results seem to debunk a myth so common it’s programmed into our lives.

For decades, experts have advised us to take 10,000 steps a day for better health. The number is even coded into fitness trackers as a goal. It’s not entirely clear where it came from, though it seems to have originated in the 1960s with Japanese pedometers called manpo-kei, which translates to “10,000 steps meter,” Lee and others say.

Lee wondered if 10,000 was some magic number.

Figuring things like this out is not easy. Most studies on the long-term value of physical activity, if they occur outside a controlled, laboratory setting, rely on self-reporting, which is often inaccurate. Lee and her colleagues solved that by examining data on 16,741 women, ages 62 to 101, who wore accelerometers to measure their movement for a seven-day period during a multi-year study on other aspects of their health.

During four years of follow-up, 504 of the women in the study died. More than half of that group — 275 — had walked only 2,700 steps a day during their test periods. Those who walked more but still a modest amount — 4,400 steps a day — were at 41 percent lower risk of death. The risk of dying prematurely continue to drop up to 7,500 steps a day, then leveled off.

And here’s a kicker: Among people who took the same number of steps during the day, how slow or fast they walked did not matter.

“For many older people, or inactive persons, 10,000 steps/day can be a very daunting goal,” Lee says in an email. She’s got a prescription, based on the study results: “If you are inactive, just adding a very modest number of steps a day — say, an additional 2,000 steps extra — can be very beneficial for your health… you don’t need to get to 10,000.” And, she adds, don’t think of the steps as “exercise.” Any ol’ ambling will do. For example, she suggests, rather than finding the closest parking spot at the grocery store or at a concert, “park at the first spot you can” and hoof it over.

The results were published May 29 in the journal JAMA Internal Medicine.

Oh, and guys? A bit of walking should be just as good for you, too.

“I believe the findings are applicable to men of similar age,” Lee says, “because previous research into physical activity and its benefits for preventing premature mortality and enhancing longevity (which are primarily studies using self-reported physical activity, rather than the device measured steps we used) have shown that there are no differences between men and women.”

She figures the findings would also apply to people in their fifties.

Novel and meaningful as Lee’s study is, it does not prove cause-and-effect. Steps may improve health, or healthier people may take more steps. But Lee and her colleagues say the findings are “more likely causal than not,” given that they excluded from the study women with heart disease, cancer, diabetes, plus anyone who rated their health as less than good.

“This study is a great contribution” to the literature showing the value of moderate physical activity, says Tom Yates, who studies the health aspects of physical activity at the University of Leicester.

“I think over the next couple of years we will see a change in the ‘more is better’ mentality that has currently dominated, at least in terms of all-cause mortality,” says Yates, who was not involved in Lee’s work. “At the opposite end of the spectrum, there is also mounting evidence that exercising to excess can be damaging for the heart and course long term damage.”

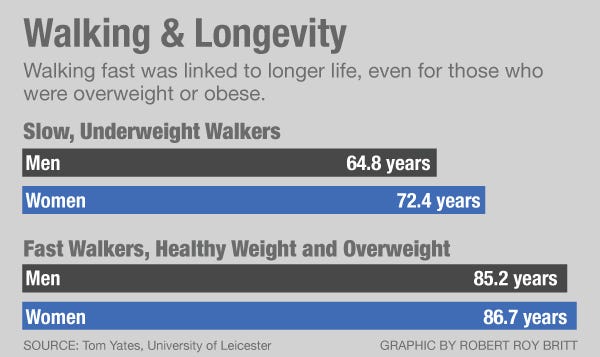

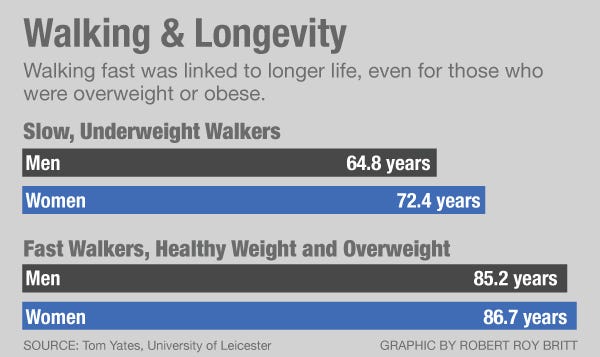

In May, Yates and his colleagues learned something about walking that is a little different than the results of Lee’s study. People who described themselves as brisk walkers (versus steady or slow) live notably longer, the researchers reported in the journal Mayo Clinic Proceedings. The study involved 474,919 people with data across seven years. And while the data relied on self-reporting of activity, the results were surprising in one respect: They held regardless of body mass index (BMI), body fat percentage or waist size.

“Fast walkers have a long life expectancy across all categories of obesity status, regardless of how obesity status is measured,” Yates says.

The study establishes a link, but doesn’t prove a cause. Perhaps naturally healthier people are just apt to walk faster. Yates is currently involved in research that will mirror Lee’s study, using objective data, he says.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention defines a brisk pace as being able to talk but not sing while you walk. That’s about 100 steps per minute for most people, according to one recent study. Based on Lee’s research above, that means 44 minutes per day of shuffling along—around the house, at work, or on an evening stroll—to get the health benefits seen at 4,400 steps.

Federal health officials say adults should get at least 2.5 hours weekly (21 minutes a day) of moderate physical activity, such as brisk walking, or 75 minutes of vigorous exercise, plus do some muscle-strengthening exercises. Children and adolescents should get at least one hour of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity daily. Such activity improves everything from mood and energy level to sleep and cognitive abilities, along with blood pressure and other physical health measures, according to the American Heart Association.

Problem is, the vast majority of Americans, young and old, don’t achieve the minimum standards.

Health officials recognize this problem and are beginning to emphasize physical activity over the torture of exercise. In fact, in the latest federal guidelines from the Department of Health & Human Services, the word “exercise” appears once, versus 40 instances of “physical activity.”

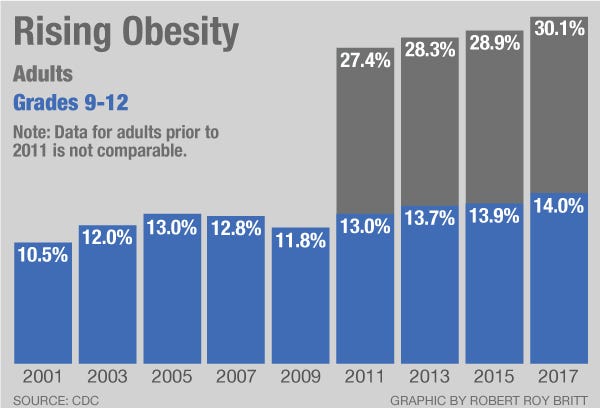

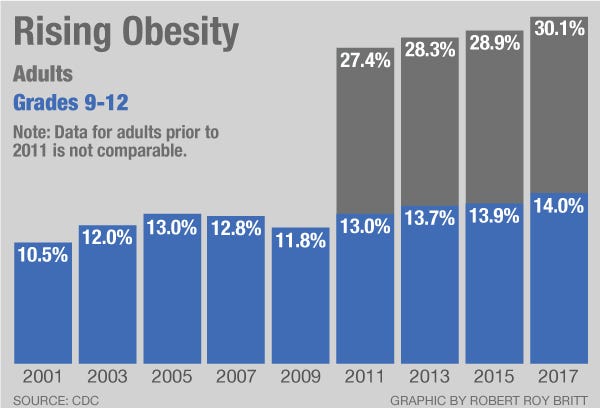

And despite a dearth of research on walking and childhood health, the federal government now targets youth with the “walking is good” message, too. As video games replace outdoor play and PE classes get canceled across the country, inactivity has become the norm and obesity rates continue to rise. Nearly half of youth age 12 to 21 are not vigorously active on a regular basis, according to the Surgeon General, and by high school only a quarter of students meet the minimum threshold of recommended activity.

So now, the Surgeon General has this message for kids and adolescents (and their parents):

“Physical activity need not be strenuous to be beneficial. Moderate amounts of daily physical activity are recommended for people of all ages. This amount can be obtained in longer sessions of moderately intense activities, such as brisk walking for 30 minutes, or in shorter sessions of more intense activities, such as jogging or playing basketball for 15–20 minutes.”

The Surgeon General’s Step it Up! program even calls for schools to create programs and policies that promote walking to school and walking throughout the school day.

While research suggests inactivity in youth sets a pattern liable to persist for life, other research finds it’s never too late to become active and enjoy at least a good chunk of the benefits: While a lifetime of physical activity is most beneficial at extending life, one study finds, sedentary people who become active in midlife can see their mortality risk drop by 30 to 35%.

Walking and other forms of moderate physical activity aren’t just good for the body but can also boost brain power, many studies have shown.

Columbia University researcher Yaakov Stern took 132 people who were not exercising, ranging in age from 20 to 67, and split them into two groups. One did stretching and toning for six months. The other group engaged in moderate aerobic exercise four times a week, including walking on a treadmill or pedaling a stationary bike. Then everyone took a test to measure executive function, the ability to pay attention, organize and achieve goals.

“The people who exercised were testing as if they were about 10 years younger at age 40 and about 20 years younger at age 60,” Stern says. The results were presented in January in the online version of the journal Neurology.

Scientists don’t know exactly how physical activity benefits the brain, but it has been shown to boost mood, reduce stress and help improve sleep — things that are in turn known to improve brain power. When we exercise, chemicals are released in the brain that keep brain cells healthy and grow new blood vessels, according to Harvard Medical School.

When one group of researchers reviewed 14 controlled trials that examined the effects of aerobic exercise on the hippocampus, a brain region involved in verbal memory and learning, they found “significant positive effects on left hippocampal volume” compared to those who didn’t exercise. More brain, more brain power.

Moderate physical activity can also combat depression and even fuel happiness.

Research published in the journal JAMA Psychiatry in January used accelerometers to measure activity, along with DNA analysis. “Using genetic data, we found evidence that higher levels of physical activity may causally reduce risk for depression,” says Massachusetts General Hospital researcher Karmel Choi, lead author of the study. And it doesn’t take a lot. “Any activity appears to be better than none,” Choi says.

None of this is a knock on vigorous exercise. The health benefits from intense physical activity, even short but intense aerobic efforts or challenging weightlifting sessions as brief as 13 minutes, are well demonstrated. If that’s your thing, stick with it, so long as you don’t overdo. As the CDC puts it: “Greater amounts of physical activity are even more beneficial, up to a point. Excessive amounts of physical activity can lead to injuries, menstrual abnormalities, and bone weakening.”

But if the very word “exercise” gives you hives, then forget the Spandex and the hundred-dollar shoes, cancel that unused gym membership, and donate that rusty aerobic contraption to charity. Then go for a walk.

Lee is an epidemiologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Massachusetts who focuses on how physical activity can promote health and prevent chronic disease. Her latest study is actually about steps. Specifically: How many, or how few, an older person needs to take on a daily basis to reap significant health perks.

Along with several other studies out this year, the results reveal the incredible power of simply doing what humans have done since we stopped swinging from trees. And Lee’s results seem to debunk a myth so common it’s programmed into our lives.

For decades, experts have advised us to take 10,000 steps a day for better health. The number is even coded into fitness trackers as a goal. It’s not entirely clear where it came from, though it seems to have originated in the 1960s with Japanese pedometers called manpo-kei, which translates to “10,000 steps meter,” Lee and others say.

Lee wondered if 10,000 was some magic number.

Figuring things like this out is not easy. Most studies on the long-term value of physical activity, if they occur outside a controlled, laboratory setting, rely on self-reporting, which is often inaccurate. Lee and her colleagues solved that by examining data on 16,741 women, ages 62 to 101, who wore accelerometers to measure their movement for a seven-day period during a multi-year study on other aspects of their health.

During four years of follow-up, 504 of the women in the study died. More than half of that group — 275 — had walked only 2,700 steps a day during their test periods. Those who walked more but still a modest amount — 4,400 steps a day — were at 41 percent lower risk of death. The risk of dying prematurely continue to drop up to 7,500 steps a day, then leveled off.

And here’s a kicker: Among people who took the same number of steps during the day, how slow or fast they walked did not matter.

“For many older people, or inactive persons, 10,000 steps/day can be a very daunting goal,” Lee says in an email. She’s got a prescription, based on the study results: “If you are inactive, just adding a very modest number of steps a day — say, an additional 2,000 steps extra — can be very beneficial for your health… you don’t need to get to 10,000.” And, she adds, don’t think of the steps as “exercise.” Any ol’ ambling will do. For example, she suggests, rather than finding the closest parking spot at the grocery store or at a concert, “park at the first spot you can” and hoof it over.

The results were published May 29 in the journal JAMA Internal Medicine.

Oh, and guys? A bit of walking should be just as good for you, too.

“I believe the findings are applicable to men of similar age,” Lee says, “because previous research into physical activity and its benefits for preventing premature mortality and enhancing longevity (which are primarily studies using self-reported physical activity, rather than the device measured steps we used) have shown that there are no differences between men and women.”

She figures the findings would also apply to people in their fifties.

Novel and meaningful as Lee’s study is, it does not prove cause-and-effect. Steps may improve health, or healthier people may take more steps. But Lee and her colleagues say the findings are “more likely causal than not,” given that they excluded from the study women with heart disease, cancer, diabetes, plus anyone who rated their health as less than good.

“This study is a great contribution” to the literature showing the value of moderate physical activity, says Tom Yates, who studies the health aspects of physical activity at the University of Leicester.

“I think over the next couple of years we will see a change in the ‘more is better’ mentality that has currently dominated, at least in terms of all-cause mortality,” says Yates, who was not involved in Lee’s work. “At the opposite end of the spectrum, there is also mounting evidence that exercising to excess can be damaging for the heart and course long term damage.”

In May, Yates and his colleagues learned something about walking that is a little different than the results of Lee’s study. People who described themselves as brisk walkers (versus steady or slow) live notably longer, the researchers reported in the journal Mayo Clinic Proceedings. The study involved 474,919 people with data across seven years. And while the data relied on self-reporting of activity, the results were surprising in one respect: They held regardless of body mass index (BMI), body fat percentage or waist size.

“Fast walkers have a long life expectancy across all categories of obesity status, regardless of how obesity status is measured,” Yates says.

The study establishes a link, but doesn’t prove a cause. Perhaps naturally healthier people are just apt to walk faster. Yates is currently involved in research that will mirror Lee’s study, using objective data, he says.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention defines a brisk pace as being able to talk but not sing while you walk. That’s about 100 steps per minute for most people, according to one recent study. Based on Lee’s research above, that means 44 minutes per day of shuffling along—around the house, at work, or on an evening stroll—to get the health benefits seen at 4,400 steps.

Federal health officials say adults should get at least 2.5 hours weekly (21 minutes a day) of moderate physical activity, such as brisk walking, or 75 minutes of vigorous exercise, plus do some muscle-strengthening exercises. Children and adolescents should get at least one hour of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity daily. Such activity improves everything from mood and energy level to sleep and cognitive abilities, along with blood pressure and other physical health measures, according to the American Heart Association.

Problem is, the vast majority of Americans, young and old, don’t achieve the minimum standards.

Health officials recognize this problem and are beginning to emphasize physical activity over the torture of exercise. In fact, in the latest federal guidelines from the Department of Health & Human Services, the word “exercise” appears once, versus 40 instances of “physical activity.”

And despite a dearth of research on walking and childhood health, the federal government now targets youth with the “walking is good” message, too. As video games replace outdoor play and PE classes get canceled across the country, inactivity has become the norm and obesity rates continue to rise. Nearly half of youth age 12 to 21 are not vigorously active on a regular basis, according to the Surgeon General, and by high school only a quarter of students meet the minimum threshold of recommended activity.

So now, the Surgeon General has this message for kids and adolescents (and their parents):

“Physical activity need not be strenuous to be beneficial. Moderate amounts of daily physical activity are recommended for people of all ages. This amount can be obtained in longer sessions of moderately intense activities, such as brisk walking for 30 minutes, or in shorter sessions of more intense activities, such as jogging or playing basketball for 15–20 minutes.”

The Surgeon General’s Step it Up! program even calls for schools to create programs and policies that promote walking to school and walking throughout the school day.

While research suggests inactivity in youth sets a pattern liable to persist for life, other research finds it’s never too late to become active and enjoy at least a good chunk of the benefits: While a lifetime of physical activity is most beneficial at extending life, one study finds, sedentary people who become active in midlife can see their mortality risk drop by 30 to 35%.

Walking and other forms of moderate physical activity aren’t just good for the body but can also boost brain power, many studies have shown.

Columbia University researcher Yaakov Stern took 132 people who were not exercising, ranging in age from 20 to 67, and split them into two groups. One did stretching and toning for six months. The other group engaged in moderate aerobic exercise four times a week, including walking on a treadmill or pedaling a stationary bike. Then everyone took a test to measure executive function, the ability to pay attention, organize and achieve goals.

“The people who exercised were testing as if they were about 10 years younger at age 40 and about 20 years younger at age 60,” Stern says. The results were presented in January in the online version of the journal Neurology.

Scientists don’t know exactly how physical activity benefits the brain, but it has been shown to boost mood, reduce stress and help improve sleep — things that are in turn known to improve brain power. When we exercise, chemicals are released in the brain that keep brain cells healthy and grow new blood vessels, according to Harvard Medical School.

When one group of researchers reviewed 14 controlled trials that examined the effects of aerobic exercise on the hippocampus, a brain region involved in verbal memory and learning, they found “significant positive effects on left hippocampal volume” compared to those who didn’t exercise. More brain, more brain power.

Moderate physical activity can also combat depression and even fuel happiness.

Research published in the journal JAMA Psychiatry in January used accelerometers to measure activity, along with DNA analysis. “Using genetic data, we found evidence that higher levels of physical activity may causally reduce risk for depression,” says Massachusetts General Hospital researcher Karmel Choi, lead author of the study. And it doesn’t take a lot. “Any activity appears to be better than none,” Choi says.

None of this is a knock on vigorous exercise. The health benefits from intense physical activity, even short but intense aerobic efforts or challenging weightlifting sessions as brief as 13 minutes, are well demonstrated. If that’s your thing, stick with it, so long as you don’t overdo. As the CDC puts it: “Greater amounts of physical activity are even more beneficial, up to a point. Excessive amounts of physical activity can lead to injuries, menstrual abnormalities, and bone weakening.”

But if the very word “exercise” gives you hives, then forget the Spandex and the hundred-dollar shoes, cancel that unused gym membership, and donate that rusty aerobic contraption to charity. Then go for a walk.

1 comment:

Interesting article. I'm a male, past 75 years of age, and have no identifiable or age related illnesses. I walk briskly for at least a mile a day, and I take a couple of dozen nutritional supplements daily. I'm a short guy (5'8") so I figure I walk about 2,000 steps per mile (I've never measured my pace length, so that is a rough guess). The mile a day walk takes about 20 minutes, and thus I figure I walk at an approximate speed of 3 MPH.

I suspect that without either the nutritional supplements or the mile a day walk I would be showing more signs of aging than greying hair.

Everything we do to remain healthy counts. In my opinion.

Post a Comment