What leaps out at you is that domestication was a well understood art practiced everywhere just as plant breeding is today.

As i have posted, our future is organic and in conjunction with robot supported high density populations. Domestication and plant breeding will be practiced everywhere across the globe. Our archeological record will easily promote a number of obvious candidates.

Certainly the global demand is there,..

Hunting for the ancient lost farms of North America

2,000 years ago, people domesticated these plants. Now they’re wild weeds. What happened?

Adventurers and archaeologists have spent centuries searching for

lost cities in the Americas. But over the past decade, they’ve started

finding something else: lost farms.

Enlarge /

At Ash Cave in Ohio, archaeologists discovered an enormous cache of

seeds from lost crops, including domesticated native goosefoot (similar

to quinoa). These seeds were so far from their wild habitats that they

had clearly been domesticated.

Over 2,000 years ago in North America, indigenous people domesticated

plants that are now part of our everyday diets, such as squashes and

sunflowers. But they also bred crops that have since returned to the

wild. These include erect knotweed (not to be confused with its invasive

cousin, Asian knotweed), goosefoot, little barley, marsh elder, and

maygrass. We haven’t simply lost a few plant strains: an entire cuisine

with its own kinds of flavors and baked goods has simply disappeared.

By studying lost crops, archaeologists learn about everyday life in

the ancient Woodland culture of the Americas, including how people ate

plants that we call weeds today. But these plants also give us a window

on social networks. Scientists can track the spread of cultivated seeds

from one tiny settlement to the next in the vast region that would one

day be known as the United States. This reveals which groups were

connected culturally and how they formed alliances through food and

farming.

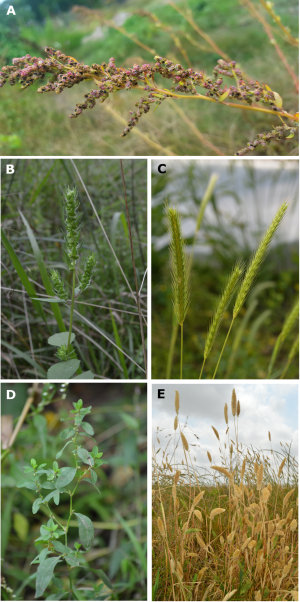

Enlarge / Here you can see some of the lost crops of North America: a) goosefoot (Chenopodium berlandieri); b) sumpweed/mars helder (Iva annua); c) little barley (Hordeum pusillum); d) erect knotweed (Polygonum erectum); e) maygrass (Phalaris caroliniana)

Natalie Mueller

is an archaeobotanist at Cornell University who has spent years hunting

for erect knotweed across the southern US and up into Ohio and

Illinois. She calls her quest the “Survey for Lost Crops,” and admits

cheerfully that its members consist of her and “whoever I can drag

along.” She’s published papers about her work in Nature, but also she spins yarns about her hot, bug-infested summer expeditions for lost farms on her blog. There, photographs of the rare wild plants are interspersed with humorous musings on contemporary local food delicacies like pickle pops.

Native to the Americas, erect knotweed grows in the moist flood zones

near rivers. It’s a stalky plant with spoon-shaped leaves, and it

produces achenes, or fruit with very hard shells to protect its rich,

starchy seeds. Though rare today, the plant was common enough 2,000

years ago that indigenous Americans collected it from the shores of

rivers and brought it with them to the uplands for cultivation.

Archaeologists have found caches of knotweed seeds buried in caves,

clearly stored for a later use that never came. And, in the remains of

ancient fires, they’ve found burned erect knotweed fruits, popped like

corn.

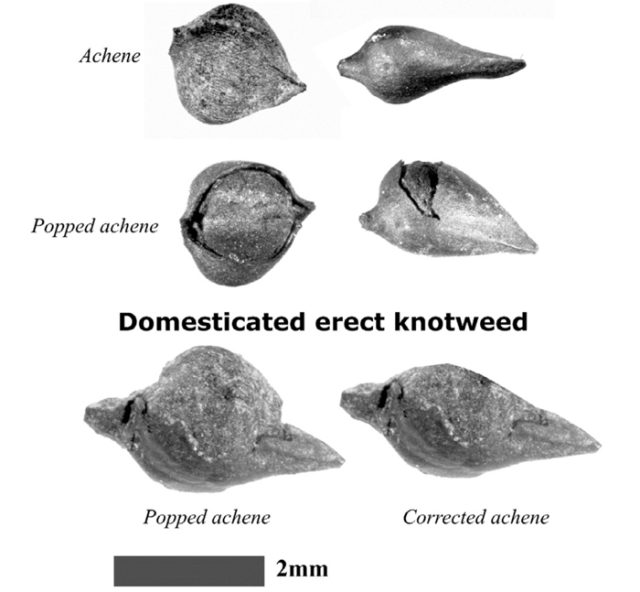

Mueller told Ars Technica that erect knotweed was likely domesticated

on tiny farms on the western front of the Appalachians. There are clear

differences between it and its feral cousins. After years of comparing

the ancient seeds with wild types, Mueller has found two unmistakable

signs of domestication: larger fruits and thinner fruit skins. We see a

similar pattern in other domesticated plants like corn, whose wild

version with tiny seeds is almost unrecognizable to people chomping on

the juicy, large kernels of the domesticated plant.

Obviously, bigger seeds would make the erect knotweed a better food

source, so farmers selected for that. And the thinner skin means the

plants can germinate more quickly. Their wild cousins evolved to produce

fruits tough enough to endure river floods and inhospitable conditions

for over a year before sprouting. But farm life is cushy for plants, so

these defenses weren’t necessary for their survival under human care.

Still, even the domesticated fruits of the erect knotweed have skins

so tough that Mueller has not been able to crack them using the stone

tools typical of the Woodland era. Working with a team at Cornell, she’s

been trying to reverse engineer how they could have been eaten.

“The fruit coat is really hard, and it would have been necessary to

break through it,” she mused. “It’s like buckwheat—the sprouts are

nutritious. So maybe they ate the sprouted version.”

As for whether early Americans ate popped knotweed like popcorn, she

was less certain. “The only way to preserve it is to burn it, so [the

remains we find] could have been accidents while cooking. It might have

been for drying.” But yes, people from long ago might have munched on

popweed.

Another possibility is that the seeds were soaked in lime before

being turned into a hominy-style porridge. Ancient Americans used

lime—the chemical, not the fruit—to soften the hulls of maize before

cooking it, in a technique called nixtamalization. It’s very likely the

Woodland peoples used this prehistoric form of culinary science on other

plants, too. So people 2,000 years ago may have been eating a rich,

knotweed mush.

Mueller is currently cultivating her own erect knotweed to test

various forms of preparation, but she’s not quite ready to go into the

kitchen yet. “I’m trying to be a good farmer and put my seeds back

first,” she said. “In five years of looking, I’ve only found seven

populations of this plant. I want to conserve the seeds as much I can.”

She’s going to accumulate a sizable cache of seeds before wasting them

on dinner.

A history of civilization in food

Because ancient people in North America built mostly with perishable

materials, traces of their farms are all we have left of their

civilizations. With a few exceptions, they didn’t leave monumental

pyramids behind or sprawling plazas. But their ability to domesticate

plants is as much a testimony to their cultural sophistication as any

stone temple.

In a recent paper for the Journal of Anthropological Archaeology,

Mueller describes finding the earliest known example of domesticated

erect knotweed at a site called Walker-Noe in central Kentucky. She

found it mostly by accident. She had assumed, based on previous studies,

that knotweed was domesticated in Illinois, possibly about 1,200 years

ago. But then she spoke with a Kentucky museum curator who told her

about a mysterious grave from the 2,000-year-old Hopewell culture, found

stuffed with seeds.

Examining the seeds, Mueller identified them as domesticated erect

knotweed. This find makes the plant’s domestication roughly a millennium

older than previously thought. But given that these fruits probably

came after generations of breeding by farmers, it hints at a much older

date.

Enlarge / The top two rows are wild erect knotweed. The wild plant produces two kinds of achene, also called fruit: on the left is one form, with a thick, wrinkled skin; on the right is a fruit with smoother, thinner skin. The domesticated strain in the bottom row—popped and unpopped—resemble the smooth form of the wild fruit. You’ll notice also that it’s generally bigger. Mueller experimentally carbonized the wild fruit to see how its popped form would match the popped domesticate.

Natalie Mueller

Mueller believes that the Hopewell shared their seeds throughout many

communities where people tended farms along the skein of rivers that

connect the American South with the Midwest. But it also seems likely

that the erect knotweed was domesticated at least twice: once in the

Kentucky region where she found her sample, and once about a thousand

years later in Illinois when the great pyramid city of Cahokia stood at the center of the Mississippian culture.

Many of these early farmers appear to have counted crops among their

greatest creations. Crops were valued trade goods and shared with allies

in the same way jewelry, projectile points, and fine pottery were. And,

of course, they were placed in graves alongside other precious funeral

goods. Farming was a science and key to survival, but it was also an

art. Food and feasting were central to indigenous cultures in the

Americas, just as they were to civilizations in Europe and Asia. Serving

guests a delightful meal with many kinds of grains, breads, and oils

would have been a source of pride and pleasure.

Losing a crop

Perhaps the strangest part of this story is the fact that people simply

stopped cultivating so many crops that were central to their diets.

Imagine what would happen if we decided to abandon wheat to the

wilderness. Suddenly, there would be no more baguettes and pastas—not to

mention cakes. Sure, we could make delicious breads from corn and tasty

noodles from rice or beans. But for many of us, it would feel like an

incredible loss of a comforting staple. No doubt, that’s how the loss of

knotweed felt to aboriginal Americans, too.

It’s likely that the Eastern Agricultural Complex (EAC)—a catch-all

term for the lost crops of North America—faded away slowly. Though we

can't be sure what triggered its decline, Mueller thinks it may have

suffered its first blow from one of the most popular crops in the

Americas: maize, which came north from Mexico about a millennium ago.

“Maize is an amazing crop,” Mueller said. “All over the world, when

it arrives, people give up their old crops and start growing it. It’s

productive and has lots of sugar so it gives you quick energy.” By the

time Cahokia was at its height in the 1000s, maize was already edging

out crops like erect knotweed.

But the death knell for erect knotweed probably came from Europe.

Archaeologists find no more examples of domesticated erect knotweed

after colonists began to settle the Americas in the 1400s, destroying

local civilizations as they went. “There was so much displacement,

disease, and warfare over the next couple hundred years that a lot of

knowledge was lost,” Mueller explained.

Still, a lot can be learned from America’s lost crops, and it’s not

just about finding the next quinoa for health-food nerds. Mueller has

been working with Smithsonian Institute anthropologist Logan Kistler

to sequence the genomes of lost domesticates. He’s fascinated by how

many of these crops went through an entire cycle of domestication and

re-wilding in the past few thousand years. Most plants that we eat, from

wheat and barley to dates and beans, were domesticated more than 10,000

years ago and never went back. The EAC offers an unprecedented glimpse

at what happens to plants when we turn them into food crops. And these

domestication events are recent enough that we can get good genomic

material from samples.

Enlarge / Archaeo-botanist Natalie Mueller with the first clump of wild erect knotweed she ever found.

Natalie Mueller

We have a fairly good sense of how domestication affects animal species over time. Domesticated pigs, horses, dogs, and even humans have all undergone physical changes, often described as “paedomorphosis,”

which means retaining infantile body features (softer faces, smaller

bodies) throughout life. But we’re just starting to understand plant

domestication. “These crops have a good archaeological record that's

well preserved,” Kistler said. “It gives us a chance to study

domestication in real time, with a good record of what comes in between

wild and domestic varieties.”

The EAC is also exciting for Kistler because it represents a diverse

group of plants. Until recently, archaeo-botanists looked mostly at

domestic plants emerging in the Fertile Crescent over 10,000 years ago

during the Neolithic—but these are just grasses and legumes. In the

Americas, Kistler explained, “We’ve got five good domesticated species.

They’re taxonomically extremely diverse and yet grown in same fields and

harvested at the same time. It builds in a little bit of control for

looking at multiple species.”

Once he’s been able to sequence these crops, we may begin to see

common domestication patterns across plant species. Likely they’ll be

things like fast germination and larger fruit size, but we may find some

surprises, too.

For Mueller, the search for erect knotweed isn’t just about

understanding the mechanisms of domestication. It’s also about coming to

terms with everything we’ve lost.

“I want to identify as many populations of these species as possible

before they go extinct, because they are all threatened,” she said.

She’s learned about how ancient Americans encountered these plants and

how they incorporated them into their lives. But she’s also learned

about how much the American landscape is still changing.

“I was out from October to November, driving around looking for

populations of these plants. Partly it’s based on records from botanists

going back at least 100 years.” Sometimes plants are still growing

where they were a century ago, she said, but sometimes they aren’t.

“You realize how much the land has changed even in 100 years,”

Mueller reflected. “There are so few places for native species to grow.”

No comments:

Post a Comment