https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2019/02/08/reading-in-the-age-of-constant-distraction/

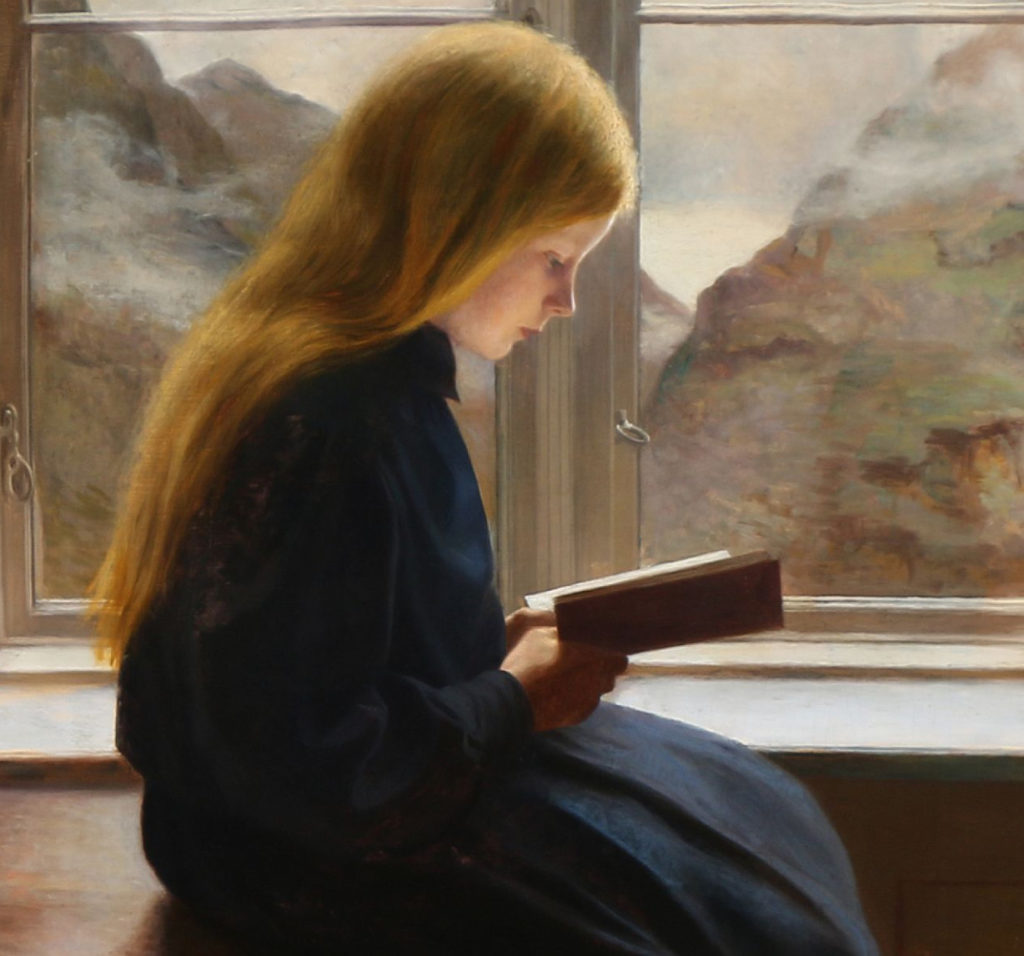

Johan Gudmundsen-Holmgreen, Laesende lille pige, 1900

“I read books to read myself,” Sven Birkerts wrote in The Gutenberg Elegies: The Fate of Reading in an Electronic Age.

Birkerts’s book, which turns twenty-five this year, is composed of

fifteen essays on reading, the self, the convergence of the two, and the

ways both are threatened by the encroachment of modern technology. As

the culture around him underwent the sea change of the internet’s

arrival, Birkerts feared that qualities long safeguarded and elevated by

print were in danger of erosion: among them privacy, the valuation of

individual consciousness, and an awareness of history—not merely the

facts of it, but a sense of its continuity, of our place among the

centuries and cosmos. “Literature holds meaning not as a content that

can be abstracted and summarized, but as experience,” he wrote. “It is a

participatory arena. Through the process of reading we slip out of our

customary time orientation, marked by distractedness and surficiality,

into the realm of duration.”

Writing in 1994, Birkerts worried that distractedness and

surficiality would win out. The “duration state” we enter through a

turned page would be lost in a world of increasing speed and relentless

connectivity, and with it our ability to make meaning out of narratives,

both fictional and lived. The diminishment of literature—of sustained

reading, of writing as the product of a single focused mind—would

diminish the self in turn, rendering us less and less able to grasp both

the breadth of our world and the depth of our own consciousness. For

Birkerts, as for many a reader, the thought of such a loss devastates.

So while he could imagine this bleak near-future, he (mostly) resisted

the masochistic urge to envision it too concretely, focusing instead on

the present, in which—for a little while longer, at least—he reads, and

he writes. His collection, despite its title, resembles less an elegy

for literature than an attempt to stave off its death: by writing

eloquently about his own reading life and electronic resistance,

Birkerts reminds us that such a life is worthwhile, desirable, and, most

importantly, still possible. In the face of what we stand to lose, he

privileges what we might yet gain.

A quarter of a century later, did he—did we—manage to salvage the

wreck? Or have Birkerts’s worst fears come to pass? It’s hard to tell

from the numbers. More independent bookstores are opening than closing, and sales of print books are up—but authors’ earnings are down. Fewer Americans read for pleasure than they once did. A major house’s editor-driven imprint was shuttered recently, while the serialized storytelling app Wattpad announced

its intention to publish books chosen by algorithms, foregoing the need

for editors altogether. Some of the changes Birkerts saw on the

horizon—the invention of e-books, for one, and the possibilities of

hypertext—have turned out to be less consequential than anticipated, but

others have proven dire; the easy, addictive distractions of the screen

swallow our hours whole.

And perhaps the greatest danger posed to literature is not any

newfangled technology or whiz-bang rearrangement of our synapses, but

plain old human greed in its latest, greatest iteration: an online

retailer incorporated in the same year The Gutenberg Elegies

was published. In the last twenty-five years, Amazon has gorged on late

capitalism’s values of ease and cheapness, threatening to monopolize not

only the book world, but the world-world. In the face of such an

insidious, omnivorous menace—not merely the tech giant, but the culture

that created and sustains it—I find it difficult to disentangle my own

fear about the future of books from my fear about the futures of

small-town economies, of American democracy, of the earth and its rising

seas.

“Ten, fifteen years from now the world will be nothing like what we

remember, nothing much like what we experience now,” Birkerts wrote. “We

will be swimming in impulses and data—the microchip will make us offers

that will be very hard to refuse.” Indeed, few of us have refused them.

As each new technology, from smartphones to voice-activated home

assistants, becomes normalized faster and faster, our ability to refuse

it lessens. The choice presented in The Gutenberg Elegies,

between embrace and skepticism, hardly seems like a choice anymore: the

new generation is born swaddled in the digital world’s many arms.

I am both part and not part of this new generation. I was born in

1988, two years before the development of HTML. I didn’t have a computer

at home until middle school, didn’t have a cell phone until I was

eighteen. I remember the pained beeping of a dial-up connection, if only

faintly. Facebook launched as I finished up high school, and Twitter as

I entered college. The golden hours of my childhood aligned perfectly

with the fading light of a pre-internet world; I know intimately that

such a world existed, and had its advantages.

Birkerts, recalling the power books held over him when he was young,

writes, “Through reading and living I have gradually made myself proof

against total ravishment by authors. Yet so vivid are my recollections

of that urgency, that sense of consequence, that I foolishly keep

looking for it to happen again.” The heightened state brought on by a

book—in which one is “actively present at every moment, scripting and

constructing”—is what readers seek, Birkerts argues: “They want plot and

character, sure, but what they really want is a vehicle that will bear

them off to the reading state.” This state is threatened by the

ever-sprawling internet—can the book’s promise of deeper presence entice

us away from the instant gratification of likes and shares?

“[Y]ears of working in bookstores have convinced me that this

fundamental condition is there for others as well,” Birkerts writes; as a

young man, he worked for a then-independent Ann Arbor bookshop called

Borders. Four decades later, I slung books at Literati Bookstore, a few

blocks away. The shelves of the original Borders had been bought and

repurposed by Literati’s owners to hold the new store’s fiction section,

and the people browsing them were the same, too: that is, they had the

same tilt to their heads as they scanned titles, the same hopeful reach

in their fingers as they pulled a volume down, flipping through the

first few pages.

And if they occasionally wanted books modeled after the internet—gift

books born on Tumblr, Instagram printed out and bound—they also wanted

Maggie Nelson’s Bluets. They wanted Teju Cole’s Open City, Anthony Marra’s The Tsar of Love and Techno, Claudia Rankine’s Don’t Let Me Be Lonely.

Loneliness is what the internet and social media claim to alleviate,

though they often have the opposite effect. Communion can be hard to

find, not because we aren’t occupying the same physical space but

because we aren’t occupying the same mental plane: we don’t read the

same news; we don’t even revel in the same memes. Our phones and

computers deliver unto each of us a personalized—or rather,

algorithm-realized—distillation of headlines, anecdotes, jokes, and

photographs. Even the ads we scroll past are not the same as our

neighbor’s: a pair of boots has followed me from site to site for weeks.

We call this endless, immaterial material a feed, though there’s little sustenance to be found.

Birkerts’s argument (and mine) isn’t that books alleviate loneliness,

either: to claim a goal shared by every last app and website is to lose

the fight for literature before it starts. No, the power of art—and

many books are, still, art, not entertainment—lies in the way it turns

us inward and outward, all at once. The communion we seek, scanning

titles or turning pages, is not with others—not even the others, living

or long dead, who wrote the words we read—but with ourselves. Our finest

capacities, too easily forgotten.

Early in The Gutenberg Elegies, Birkerts summarizes

historian Rolf Engelsing’s definition of reading “intensively” as the

common practice of most readers before the nineteenth century, when

books, which were scarce and expensive, were often read aloud and many

times over. As reading materials—not just books, but newspapers,

magazines, and ephemera—proliferated, more recent centuries saw the rise

of reading “extensively”: we read these materials once, often quickly,

and move on. Birkerts coins his own terms: the deep, devotional practice

of “vertical” reading has been supplanted by “horizontal” reading,

skimming along the surface. This shift has only accelerated dizzyingly

in the time since Engelsing wrote in 1974, since Birkerts wrote in 1994,

and since I wrote, yesterday, the paragraph above.

Horizontal reading rules the day. What I do when I look at Twitter is

less akin to reading a book than to the encounter I have with a

recipe’s instructions or the fine print of a receipt: I’m taking in

information, not enlightenment. It’s a way to pass the time, not to live

in it. Reading—real reading, the kind Birkerts makes his impassioned

case for—draws on our vertical sensibility, however latent, and “where

it does not assume depth, it creates it.”

I no longer have a Facebook account, and I find myself spending less

and less time online. As adulthood settles on me—no passing fad, it

turns out, but a chronic condition—I’m increasingly drawn back to the

deeply engaged reading of my childhood. The books have changed, and my

absorption is not always as total as it once was, but I can still find,

slipped like a note between the pages, what Birkerts calls the “time of

the self… deep time, duration time, time that is essentially

characterized by our obliviousness to it.” The gift of reading, the gift

of any encounter with art, is that this time spent doesn’t leave me

when I lift my eyes from the book in my lap: it lingers, for a minute or

a day. “[S]omething more than definitional slackness allows me to tell a

friend that I’m reading The Good Soldier as we walk down the street together,” Birkerts writes. “In some ways I am reading the novel as I walk, or nap, or drive to the store for milk.”

Unfortunately, this thrumming-under quality is also true of our

horizontal reading. If I’ve spent too long before the pixelated page,

that experience, too, clings to the hours that follow. The screen

appears before my closed eyes; my thoughts vibrate at the frequency of content, of discourse:

pithy, argumentative, living in anticipation of retort. I debate

imagined trolls in the shower. “When a work compels immersion, if often

also has the power to haunt from a distance,” Birkerts says, and how I

wish this haunting were the sole province of great work. It isn’t:

ghosts seep through the words on the screen, ghosts of screeds and

inanities, of hate and idiocy, of so much—so much!—bad writing.

“But perhaps when the need is strong enough we will seek out the word

on the page, and the work that puts us back into the force field of

deep time,” says Birkerts. “The book—and my optimism, you may sense, is

not unwavering—will be seen as a haven, as a way of going off-line and

into a space sanctified by subjectivity.” Oddly enough, here in the

dawning days of 2019, my own optimism is strong. It seems clear to me

that the need is strong enough—is as strong as it always has been and

always will be—for the blossoming, bodily pleasure of reading something

remarkable, the way it takes the top of my head off and shows me—palms

open, an offering—what’s been churning away in there, all along.

“Resonance—there is no wisdom without it,” Birkerts writes.

“Resonance is a natural phenomenon, the shadow of import alongside the

body of fact, and it cannot flourish except in deep time.” But time

feels especially shallow these days, as the wave of one horror barely

crests before it’s devoured by the next, as every morning’s shocking

headline is old news by the afternoon. Weeks go by, and we might see

friends only through the funhouse mirrors of Snapchat and Instagram and

their so-called stories, designed to disappear. Not even the pretense of

permanence remains: we refresh and refresh every tab, and are not

sated. What are we waiting for? What are we hoping to find?

We know perfectly well—we remember, even if dimly, the inward state

that satisfies more than our itching, clicking fingers—and we know it

isn’t here. Here, on the internet, is a nowhere space, a

shallow time. It is a flat and impenetrable surface. But with a book, we

dive in; we are sucked in; we are immersed, body and soul. “We hold in

our hands a way to cut against the momentum of the times,” Birkerts

assures. “We can resist the skimming tendency and delve; we can restore,

if only for a time, the vanishing assumption of coherence. The beauty

of the vertical engagement is that it does not have to argue for itself.

It is self-contained, a fulfillment.”

No comments:

Post a Comment