In the middle of the night a ship founders and a handful of men are lost forever. Because they were illegally crossing a border, no evidence is left behind. How often has this happened in history? It is very difficult for others to track those last steps. let alone confirm the actual death. Yet time itself is ample confirmation.

In this case we see the likely story and uncover others also lost as well. That fact alone confirms the base story. .

We live today with millions forced into motion. Many are falling through the cracks. It is all a dynamic mix of victims and exploiters with governments constantly back footed.

..

Without a Trace

Missing, in an age of mass displacement

In December

2015, a twenty-two-year-old man named Masood Hotak left his home in

Kabul, Afghanistan, and set out for Europe. For several weeks, he made

his way through the mountains of Iran and the rolling plateaus of

Turkey. When he reached the city of Izmir, on the Turkish coast, Masood

sent a text message to his elder brother Javed, saying he was preparing

to board a boat to Greece. Since the start of the journey, Javed, who

was living in England, had been keeping tabs on his younger brother’s

progress. As Masood got closer to the sea, Javed had felt increasingly

anxious. Winter weather on the Aegean was unpredictable, and the

ramshackle crafts used by the smugglers often sank. Javed had even

suggested Masood take the longer, overland route, through Bulgaria, but

his brother had dismissed the plan as excessively cautious.

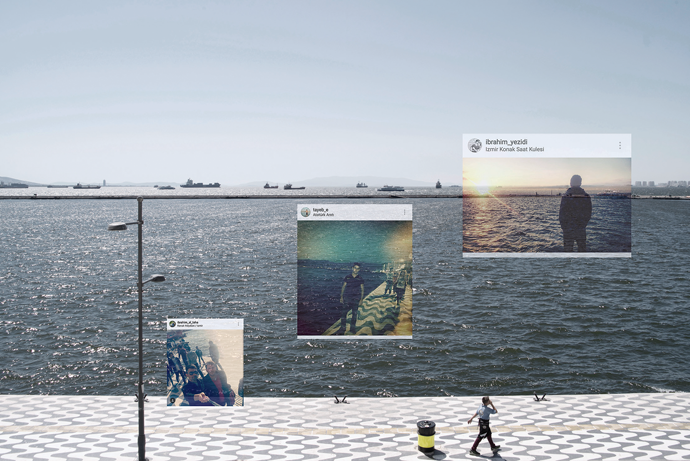

Lesbos, Greece, 39°22’44.5″ N, 26°14’46.9″ E, a still from Traces of Exile,

a mixed-media installation by Tomas van Houtryve. Inspired by an

augmented-reality app that layers a smartphone camera’s view with nearby

social-media posts, the artist captured Instagram selfies posted by

refugees on their journeys through Turkey, Greece, and elsewhere in

Europe in 2017 and juxtaposed the images over footage of the locations

where the social-media posts were created. © Tomas van Houtryve/VII

Finally, on January 3, 2016, to Javed’s immense relief, Masood sent a

series of celebratory Facebook messages announcing his arrival in

Europe. “I reached Greece bro,” he wrote. “Safe. Even my shoes didn’t

get wet.” Masood reported that his boat had come ashore on the island of

Samos. In a few days, he planned to take a ferry to the Greek mainland,

after which he would proceed across the European continent to Germany.

But then, silence. Masood stopped writing. At first, Javed was

unworried. His brother, he assumed, was in the island’s detention

facility, waiting to be sent to Athens with hundreds of other migrants.

Days turned into weeks. Every time Javed tried Masood’s phone, the call

went straight to voicemail. After a month passed with no word, it dawned

on Javed that his brother was missing.

When I first met Javed, eighteen months later, I almost didn’t

recognize him. His profile photo on Facebook, taken shortly before

Masood disappeared, showed a tall, formidably muscled man with shoulders

like cannonballs. The figure greeting me at the Birmingham airport,

however, was skinny and stooped—conspicuously deflated. Ever since his

brother went missing, Javed explained, he had stopped working out, and

he’d lost thirty pounds. Javed had begun to vanish in other ways, too,

no longer bothering to see friends or attend mosque. Going about the

errands of daily life, he said, felt pointless, obscene.

Over black tea and tinned cookies, Javed told me that when Masood had

announced his intention to leave for Europe, he had tried to change his

brother’s mind. A former soldier, Javed had himself left Afghanistan in

2008, after being threatened by the Taliban. But, when he arrived in

the United Kingdom, his request for asylum was denied. In the years

since, waiting for another visa application to be considered, he’d led a

grim, purgatorial existence—sharing a room with three other

undocumented immigrants, toiling away at low-paying “black” jobs in

takeout restaurants and car washes—able neither to begin a new life nor

return to his old one. Living in the EU, he’d told Masood, simply wasn’t

worth the risks attendant in getting there. Better to stay home.

Masood, though, saw no future in Afghanistan. At twenty-two, he had

graduated at the top of his university class in Kabul, yet still

couldn’t find a decent job. With thousands of civilians still being

massacred every year in the war against the Taliban, Masood decided to

flee to Germany. “I could probably survive here,” he told friends, “but I

wouldn’t be able to live.”

After Masood disappeared, Javed’s first, panicked impulse was to rush

to Greece and begin a search. But he knew that the Greek government

would refuse to issue a visa to an Afghan citizen who lacked legal

residence in Europe. If Javed tried to cross a border illegally, he

stood a strong chance of being deported back to Afghanistan. He settled,

instead, on making phone calls, hundreds of them. He called police

stations, hospitals, consulates, prisons, coast guards—any entity that

might know something about Masood’s whereabouts. Most who answered

simply hung up; others pled ignorance or refused to provide information

over the phone. The Afghan embassy in Turkey and the Red Cross each

promised to make inquiries, but months passed without response.

So Javed launched his own investigation. He posted photos of his

brother on Facebook pages set up for families of missing migrants, but

these mostly attracted opportunists peddling dubious information. (A

Syrian man, for example, claimed that Masood was interned in a Cretan

sanitorium, suffering from amnesia.) Masood had said that he was making

the journey with two classmates.

Based on who had shared the last photo

Masood posted of himself on Facebook—in Istanbul, smiling in front of

the massive Obelisk of Theodosius—Javed was able to deduce the names of

his brother’s friends. He contacted their families, and learned that

they, too, had vanished. Javed also noticed on Facebook that the three

young men had all friended an Afghan man living in Istanbul named Mulla

Kaya before going missing. Surmising that this was their smuggler, he

messaged people who posted on Mulla Kaya’s page, asking after the man’s

whereabouts. All reported that Mulla Kaya had also disappeared at the

same time as the others.

The Hotak family was exceptionally close-knit, having survived

decades of conflict—the Soviet invasion, a torturous civil war, the

barbarities of the Taliban, the NATO occupation. Masood’s disappearance,

however, created a rupture without repair. His father spent days locked

in his bedroom, his mother cried endlessly, and his eight siblings felt

distant from one another in a way they had not before. Every

conversation began with “Any news?” Lacking hard information about

Masood’s fate, the family took to visiting fortune-tellers—jadoogar—all of whom offered the same vision: Masood was alive, somewhere, but in trouble.

When a year passed without further news of his brother’s whereabouts,

Javed’s friends began to gently suggest that he move on. Countless

migrants died on the way to Europe, with many families never learning

definitively of their deaths. A few months later, however, Javed

received some good news: his application for a UK visa, languishing for

years, had finally been approved. To celebrate, his girlfriend baked him

a ginger cake. It seemed that, at long last, he would be able to make a

home in Britain. But Javed couldn’t conceive of settling down while a

chance remained that his brother was still alive. His first official act

as a resident of the UK, he told me, was to apply for a permit to visit

Greece.

Having only just escaped the machinery of the immigration system,

Javed was hesitant to reenter it. Yet, as his parents’ eldest son, he

felt responsible for setting things right. Not wishing to get his

family’s hopes up, he had told no one about his trip to Greece except

his girlfriend, his elder sister, and me, with an invitation to come

along.

“Be careful,” his sister told him. “We’ve already lost one brother.”

Athens, Greece, 37°59’01.7″ N, 23°43’39.1″ E, a still from Traces of Exile © Tomas van Houtryve/VII

We are entering an age of mass

displacement, bearing witness to the first tentative gestures of what

promises to be a titanic redistribution of the world’s citizenry. More

than 68 million people are currently exiled from their homes by

violence, more than at any other point in recorded history. By 2050,

according to a recent study by the World Bank, at least another

140 million people will be forced to relocate because of the effects of

climate change. Accelerating inequality, meanwhile, continues to drive

inhabitants of poor regions to wealthier ones. While the most recent

exodus of refugees from wars in the Middle East into Europe has peaked,

such colossal population transfers will soon become routine.

In the midst of this unprecedented wave of dislocation, thousands of

migrants disappear every year. These disappearances are a function,

largely, of the imperatives of secret travel. Lacking official

permission to cross borders, “irregular migrants” are compelled to move

covertly, avoiding the gaze of the state. In transit, they enter what

the anthropologist Susan Bibler Coutin has called “spaces of

nonexistence.” Barred from formal routes, some of them are pushed onto

more hazardous paths—traversing deserts on foot or navigating rough seas

with inflatable rafts. Others assume false identities, using forged or

borrowed documents. In either case, aspects of the migrant’s identity

are erased or deformed.

This invisibility cuts both ways. Even as it allows an endangered

group to remain undetected, it renders them susceptible to new kinds of

abuse. De facto stateless, they lack a government’s protection from

exploitation by smugglers and unscrupulous authorities alike. Seeking

safe harbor, many instead end up incarcerated, hospitalized, ransomed,

stranded, or sold into servitude. In Europe, there is no comprehensive

system in place to trace the missing or identify the dead. Already

living in the shadows, migrants who go missing become, in the words of

Jenny Edkins, a politics professor at the University of Manchester,

“double disappeared.”

Taken as a whole, their plight constitutes an immense, mostly hidden

catastrophe. The families of these migrants are left to mount

searches—alone and with minimal resources—of staggering scope and

complexity. They must attempt to defy the entropy of a progressively

more disordered world—seeking, against long odds, to sew together what

has been ripped apart.

Javed was a decade older than Masood

and hadn’t seen his brother in person for years, but, speaking regularly

by phone, the two had remained close. His little brother, Javed told

me, has—he always spoke of Masood in the present tense—a flamboyant,

risk-taking streak. Back in Afghanistan, their mother forbade her

children to own motorbikes, so Masood borrowed a friend’s and went

zipping around Kabul in a leather jacket. On holidays, he’d terrify his

parents by visiting classmates in distant Taliban-controlled provinces.

While most Afghan teenagers played soccer or cricket, Masood practiced kushti,

an ancient martial art where opponents wrestle each other in a dirt

pit. Yet, Masood was forgiven his hell-raising because he was also sweet

and generous, not to mention uncommonly bright—the first of his

siblings to graduate college.

By the time Javed set out for Greece, nearly two years had passed

since Masood had disappeared. After such a long silence, it would seem

unlikely that his brother was still alive. Many migrants crossing the

Aegean, of course, were swallowed by the sea. But many, too, were

swallowed up by bureaucracy. It was not unusual, Javed had heard, for

migrants traveling without papers to be detained indefinitely, left to

languish in prisons or camps with no way to contact their relatives, or

held as captives and forced to work in locked sweatshops. Refugee

communities in Birmingham abounded with tales of miraculous reunions.

Javed believed that his brother was out there somewhere, in need of

help. “I would give an eighty-percent chance that Masood is alive,” he

told me.

When Javed arrived in Athens, his first appointment was with the

Greek police. He hoped they would take up the search for his brother,

though he was apprehensive about interacting with them. In 2008, when

Javed had fled from Afghanistan to Greece, he had been held in a

detention facility for two weeks, then ordered to exit the country. But

when he tried to cross the border into Macedonia, the Greek guards

pummeled him with sticks. Later, when he tried to catch a ship to Italy,

police again beat him. It was confusing: the Greeks had clearly wanted

him to leave, but they also seemed intent on keeping him from going

anywhere.

At the police station, to Javed’s surprise, he was directed to a

polite, baby-faced detective wearing sweatpants and a skateboarding

T-shirt who shook his hand and called him “sir.” Behind the detective’s

desk hung a poster with a photo of a frightened woman, whose mouth was

clamped shut by a fleshy, distinctly masculine hand; the text read, “one phone call could free her.”

The detective listened attentively as Javed explained how Masood had

abruptly fallen out of contact after reaching Greece. But when he typed

Masood’s name into his computer, his face darkened—there was no record

of him. “Usually, with a missing person, we have something to go on,”

the detective told Javed, rolling a skinny cigarette. “But this? This is

just a name. Your brother could be anywhere.” He shrugged and smiled

sadly. “There’s really nothing we can do.”

The detective agreed to file a missing-persons report, which would be

sent out to other police departments throughout Greece. Asked for a

recent picture, Javed handed him a glossy photo of Masood. It showed a

handsome man with an inky pompadour and meticulously trimmed goatee,

cradling his baby niece. As they parted, the detective suggested that

Javed inquire on the Greek islands, where officials would have more

information about arriving migrants.

First, though, Javed wanted to check in with the Red Cross. As he

made his way through the city’s stucco canyons toward the agency’s

Athens branch, he noticed that the city had deteriorated since his visit

a decade prior. It was dirtier, every wall blemished many times over

with a mess of graffiti. Even the Greeks themselves looked

unwell—thinner, more irritable, dressed in cheaper clothes. When the

Greek government suffered its financial collapse, the country lost much

of its capacity to respond to the migrant crisis. The missing, Javed

feared, were not a priority.

The Red Cross office did little to improve his outlook. Located on

the third floor of an ugly, dun-colored building with bars on the

windows, it had the echoey feel of a company on the verge of bankruptcy.

For years the agency has operated an extensive tracing service, which

seeks to reunite people displaced by conflict. But EU privacy

regulations have prohibited the Red Cross from posting photos of missing

migrants on social media, because they are unable to give consent.

Instead, it launched a program called Trace the Face, in which family

members can post photos of themselves on the Red Cross website,

in the hope that their missing relatives will see them and choose to

make contact. Javed dismissed the entire operation as hopelessly

antiquated: even tribal Afghans, living in the Hindu Kush mountains,

have Facebook.

Javed was met by a determinedly upbeat woman who, after reviewing

Masood’s file, confirmed that the case was still open. If the Red Cross

heard anything, she told Javed, they would inform him.

Javed rubbed his face, annoyed. What, he asked, was the organization actually doing to look for his brother?

“It is our policy to not tell you the specific steps,” the woman said.

Javed frowned. “But it’s been two years.”

“I understand,” the woman said with practiced calm. “The cases of

missing persons are very complicated.” If Javed liked, she went on, he

could provide a sample of his DNA. The Red Cross maintained a database

of DNA from the families of missing migrants, which can be used to

identify corpses.

Javed was not yet ready to consider his brother’s death. He asked the

woman whether there was a chance his brother had been admitted into a

Greek hospital. She shook her head.

“I know this is frustrating,” she said. “But you must be patient.”

Javed felt a swell of anger. Struggling to maintain his composure, he stared out a window into an empty courtyard.

After a minute, the woman leaned in close to him.

“Tell me what you are thinking,” she said quietly.

“You do your searching,” he muttered. “I will do mine.”

In his final messages, Masood reported that his boat had landed on

Samos, but Javed was skeptical. Smugglers sometimes lie to passengers

about their destination, saying that they’re headed one place and then

going to another. A migrant boat leaving Izmir could possibly aim for

any one of five islands—Lesbos, Chios, Samos, Leros, and Kos—running in a

line across from the Turkish coast. Javed decided to start with the

northernmost island, Lesbos, where the majority of migrants land. In a

photo he had found on Facebook, a group of Afghan men detained in the

island’s refugee camp stood behind a tall chicken-wire fence. The

picture was blurry, but one of the figures in the background, Javed

thought, looked a lot like Masood.

Javed boarded an overnight ferry to Lesbos and slept on the floor,

above the thrumming engines. He had bad memories of his own trip to the

island, a smuggling operation likely similar to the one Masood had

taken. After arriving in Izmir, Javed had been herded at gunpoint onto a

decrepit-looking boat with two dozen other men—Iranians, Bengalis, Sri

Lankans, Kurds. Scared to put weight on the thin plywood hull, the men

arranged themselves in a ring atop the gunwales, balancing skinny bodies

with plump ones. After a few hours in the water, the outboard motor

stalled, and the raft began to sink. Half the men frantically bailed

water with baseball caps while the others paddled with their hands.

Eventually, the boat washed up on Lesbos, its passengers soaked and

traumatized. Since then, Javed had distrusted smugglers.

As Javed was deboarding in Mytilene, the capital of Lesbos, he was

intercepted by two plainclothes port officers. They checked his travel

document, searched his backpack, and allowed a large dog to sniff him

thoroughly. He was unsurprised: an Afghan man traveling openly through

Europe always invited suspicion. Waved on, Javed walked along the

harbor, past rows of pastel-colored Neoclassical buildings, until he

reached the town’s main square, which he found occupied by a half-dozen

canvas tents. A gaunt Iranian man, sitting cross-legged on a carpet,

explained that he was entering the second week of a hunger strike. The

conditions at the Lesbos refugee camp, in the town of Moria, the Iranian

said, were terrible: a handful of soiled toilets for thousands of

migrants, little food, no blankets or shoes, and a constant threat of

violence. Asked how to get there, he pointed across the street to a line

of people queuing up for a dingy shuttle bus.

We got on and trundled up a hill, passing vast groves of olive trees,

until we arrived at a cluster of white metal shipping containers

surrounded by a barbed-wire fence. Javed was briefly cheered—the camp

certainly looked like a place where someone might be held

incommunicado. But he was discouraged to spot migrants of countless

ethnicities passing in and out of the camp’s wide front gate, apparently

free to come and go as they pleased. Many carried cell phones. Slipping

past a security guard, Javed walked inside.

Constructed to accommodate two thousand migrants, the camp now held

three times that many. Piles of rotting garbage were everywhere. The

shipping containers, smelling of sweat and piss, were so crammed with

people that Javed couldn’t see the floor. For two hours he walked

around, showing people photos of his brother. One man, a

twenty-nine-year-old Afghan named Obaid, told Javed that Masood looked

familiar, but he couldn’t place him. Obaid, who was from northern

Afghanistan, spoke Dari, while Javed spoke Pashto, so they communicated

using Google Translate on their phones. Obaid explained that he, too,

had fled the Taliban. At one point, he was sent as a combat medic to a

location that Google translated as “the butcher’s area.” He had been in

Lesbos for forty-three days and was trying—like everyone else in the

camp—to get a pass to the Greek mainland. At the height of the crisis,

hundreds of migrants had been arriving on Lesbos every day. Most stayed

only briefly, just until they were issued documents allowing them to

continue on to Athens. Then, in March 2016, the European Union changed

its rules: migrants would no longer be allowed farther passage into

Europe. Only those whose asylum requests were granted could leave

Lesbos, consigning migrants like Obaid to an indefinite limbo while

their applications were processed. The camp, Javed realized, was not a

prison: the entire island was.

Before leaving Lesbos, Javed visited the police station. When

migrants land on a Greek island, their names, photographs, and

fingerprints are immediately entered into a database. Because many give

fake names—even fake nationalities—an officer agreed to show Javed

photos of all the young men who had arrived on Lesbos in early 2016. The

faces staring out of the pictures—fresh from the sea, their new life in

Europe only hours old—displayed a wide spectrum of affect, from horror

to euphoria to bland shock. Javed leaned forward until he was a few

inches from the officer’s computer screen, studying the photos one by

one. Every few seconds he whispered “no,” and the officer clicked to the

next one. Hundreds of photos later, Javed came to the end of the file.

No Masood.

Back at the dock, while waiting for a ferry to take him to the next

island, Javed was approached by an Arab migrant, who offered him an

absurd sum of money for a ticket to Athens. Javed declined, explaining

that even with a ticket, the man would still need a visa to board the

ferry. Javed showed the man a photo of Masood, but he didn’t recognize

him. As the sun began to set, Javed and the Arab watched as three

stowaways—two of them teenagers—were dragged from the ship’s dim hold.

Surrounded by a scrum of guards, they were handcuffed and made to kneel

under floodlights until they were taken away in a police wagon. The Arab

explained that they would be held in jail for the night, then released

to try again the next day.

The second island, Chios, turned out to be much like Lesbos: more

hassling by port security, more photos, more dead ends. The refugee

camp, though, was somehow in even worse condition. After checking in

with a police officer posted by the gate, Javed was escorted to a small

metal shed, which served as an office for the UN’s refugee agency.

Inside, scores of migrants with a range of requests and complaints were

laying siege to a handful of officials sporting shiny lanyards. The two

sides were engaged in a furious shouting match, carried on through a

half-dozen languages. The main official, a fat man, perspiring heavily,

seemed to be trying to quell the riot with salvos of bureaucratese—“No,

I cannot help you!” “You will need to return tomorrow!” “We have

discussed the problem with the UN and they are fully aware of it!”—but

was ignored.

Javed felt tired. He wore three days of stubble and his right heel

had swollen from constant walking, giving him a limp. After much

wrangling, he eventually got the attention of a UN staffer, who offered

him a seat and asked him about his case. But no sooner had Javed begun

answering his questions than, seemingly out of nowhere, a half dozen

police officers grabbed him, slapped him in handcuffs, and threw him in a

police car with two Syrian teenagers pulled from the camp.

Back at the police station, Javed was interrogated by two

plainclothes detectives. Why was he in Chios? What was he doing at the

camp? What was his father’s name and occupation? The detectives

inspected his phone, looking at his photos and his Facebook account.

Finally, after six hours, he was released. No explanation was given for

his detention.

While in custody, Javed was not, he would tell me later, scared—he

had committed no crime—but he was acutely aware of the precariousness of

his situation. Just as Masood had disappeared, so, he imagined, could

he. More than anything, the entire ordeal—his arrest, the thousands of

stranded refugees at the camp—struck him as both stupid and hopeless.

As we walked back to the dock, we passed a sign for an Escape the

Room game. I had noticed one on Lesbos too. “Can you escape in time?”

the sign asked. The game—players trapped in a small, claustrophobic

space, their freedom hinging on their ability to solve a series of

esoteric riddles—seemed less like frivolous entertainment than a

projection of displaced trauma. In the aftermath of World War II, more

than a million Greeks moved abroad, going to Australia, Canada, and the

United States. The anguish of migration had become part of Greek

identity, insinuated itself into the ethnic consciousness. Now the

nation was confronted with a different immigration crisis, to which it

was utterly unable to respond.

Moria refugee camp, Lesbos, 39°08’08.2″ N, 26°30’14.2″ E, a still from Traces of Exile © Tomas van Houtryve/VII

Javed had not wanted to leave

Afghanistan. His intention in becoming a soldier had been to help make

his country habitable, to secure it for future generations. When the

Taliban first rose to power in the mid-Nineties, the Hotak family had

moved to Pakistan, where they stayed for eight years. Once, during the

exile, a teenage Javed had snuck back to Kabul on an errand. Religious

police spotted him and, claiming that his hair was too long, flogged him

with an electric cable. Returning home after the American invasion,

Javed had enlisted in an elite anti-narcotics squad. Remnants of the

Taliban had transformed into an insurgency, primarily financed by heroin

sales. Javed’s unit arrested traffickers, raided drug labs, and set

fire to fields of mauve opium poppies. The insurgency, though, continued

to grow, and the Taliban soon reappeared in the Hotaks’ village. Rumors

spread that Javed, who sometimes translated for the British army, was

serving as an informant, and his relatives became targets of violent

reprisals. Javed saw that there was no way he could remain in

Afghanistan without further risking his family’s safety. With great

reluctance, he turned in his uniform and set out for Europe.

Masood had always looked up to his elder brother, and Javed worried

that Masood’s decision to emigrate was born of a desire to be like him.

In truth, he felt profoundly guilty over Masood’s disappearance.He

replayed their last discussions over and over in his mind. If only he

had been able to talk his brother out of making the trip, Javed thought,

he would never have gone missing. Yet, if he could find Masood and save

him, all would be made right.

The first two Greek islands had been discouraging, but Javed arrived

on Samos optimistic. Samos, after all, was where Masood had said that

his boat had landed. The night before, Javed had dreamed that Masood had

shown up at his family’s village in Afghanistan, bringing everyone

chocolates.

But at the police station, the officer on duty told Javed bluntly

that after two years, there was almost no chance Masood was still alive.

Javed winced. “Yes, there is a chance,” he said. “He could be in jail, where he has no phone.”

“This place does not exist,” the officer said, shaking his head. “In

Greece, even in prison, all the murderers make phone calls.”

“My friend,” another officer interjected. “I do not know if you know

this, but sometimes? People come from Turkey and—” He dipped his hand

downward, indicating a sinking ship.

Masood said he had landed on Samos on January 3. For the rest of that

week, according to the coast guard, the Aegean Sea had been so rough

that no boats had been able to land on the island. Winds had been

blowing at gale-force levels, and no one who fell overboard could have

survived the freezing water. On January 4, two rafts filled with

refugees had crashed into rocks off the Turkish coast, killing

thirty-four. In the weeks that followed, a handful of unidentified

bodies had washed up on the Greek islands—casualties, presumably, of

other, unreported shipwrecks. An officer informed Javed that only one

unidentified male body, which appeared to be that of a man in his early

twenties, had been discovered on Samos, on January 16.

Javed, suddenly ashen, pulled out a photo of Masood.

“Do you think it’s him?” he asked.

“I cannot identify him,” the officer said, taken aback. “You must do it.”

Inserting a thumb drive into his computer, the officer summoned an

image of the body. Javed, holding his breath, turned to face it.

Drowning, he was reminded, was a violent death. The photo showed a naked

man in a body bag. His face was coated with sand, his mouth rimmed with

dried foam. Streaks of crusted blood trailed, horribly, from his ears,

mouth, eyes, and scalp. The photo had been poorly composed, shot from a

canted angle that seemed to distort the corpse’s features. For several

minutes, Javed looked back and forth between the image on the screen and

the one in his hand. Finally, he shook his head. It wasn’t Masood.

Wiping tears from his eyes, he left the station.

A little while later, over coffee, I asked Javed how he was doing.

“Okay,” he said, smiling barrenly. His devastation, however, was

obvious. Throughout our journey, Javed spoke little and would seldom

admit to being anything other than okay. Often, he had the deadpan

countenance of someone actively suppressing deep pain. Allowing any

emotion out would, I imagined, render his investigation impossible.

Over the next few days, Javed pressed on to the last two islands,

Leros and Kos. The results were no better. Finding no sign of Masood, he

decided to continue on to Turkey, only three miles across the water.

When he went to purchase a ticket, however, the travel agent informed

him that his documents did not grant him entry to Turkey, which is not a

member of the EU. Instead of taking a forty-five-minute ferry, Javed

would have to fly all the way back to England and apply for a visa at

the Turkish embassy in London.

On the plane home, Javed, exhausted, looked out his window. Far

below, white clouds cast dark shadows on the Aegean’s great,

obliterating plain.

One day on Lesbos, I went looking for a

cemetery. For a long time, the bodies of unidentified migrants that

washed up on the island’s beaches were routinely buried in unmarked

graves. Overwhelmed by the number of unclaimed dead, local authorities

soon ran out of money for interment, leaving plots to be dug by

volunteers. Simon Robins, a researcher at the University of York who

visited Lesbos in 2015, reported that many of the resulting efforts were

little more than shallow holes—“bodies . . . lightly covered by earth

with only a piece of broken marble on the grave.”

Seeking to remedy this

insult, a local Egyptian man established a new cemetery, exclusively

for migrants, one in which their final resting places were well marked

and their corpses prepared with full Islamic rights. Yet, sometime

later, this charitable caretaker left the island—driven off, it was

rumored, by supporters of Golden Dawn, the Greek neo-fascist group.

Curious what had become of the Egyptian’s cemetery, I took a taxi out

to the village of Kato Tritos, where it was said to have been erected.

But, after circling the village several times, I could find no sign of

anything resembling a burial ground. Eventually, an elderly man riding a

moped spotted me and, after a long, confused exchange of poor English

and abysmal Greek, agreed to take me to the site. He drove me down a

succession of dirt roads splitting fields of wizened myrtles before

stopping next to a vast, unremarkable plot of grass. Two strands of a

barbed-wire fence, I saw, had been pulled apart, making a small,

person-size hole. The man pointed into the middle distance, gestured for

me to proceed, then sped away.

Ducking through, I walked for a long time, finding nothing but

daisies and milk thistle. I was just beginning to worry that I’d been

the victim of a prank when, suddenly, an enormous black bumblebee rose

up toward my face. Startled, I stumbled backward and tripped on what I

assumed was a rock. It was, of course, a headstone. Looking more

closely, I saw that there were headstones everywhere. I was standing on a

necropolis, now badly untended and overrun with weeds. The weeds, I

noticed with a throb of nausea, grew highest over the grave sites.

Dozens of such potter’s fields have been dug throughout southern

Europe. Similar cemeteries exist in North Africa, Yemen, Malaysia, and

the borderlands of the United States and Mexico. Death can come to a

migrant in many ways—perishing from heatstroke in the Libyan desert,

freezing in the mountains of Bulgaria, suffocating in an overstuffed

truck in Hungary, or being executed by a smuggler as punishment for

moving too slowly. Yet, with few governments taking measures to record

these deaths, the invisibility that such migrants endure during life,

notes the immigration scholar Robin Reineke, follows them to the grave.

When people die while traveling through legal channels—say, a plane

crashes or a yacht sinks—the right of families to know about the

disposition of the dead is self-evident. There are sophisticated methods

to gather clues as to the dead’s identity. Evidence—clothes,

documents—is preserved, identifying marks—scars, tattoos, dental

records—noted, witness statements taken, DNA extracted and stored.

These techniques, however, are seldom applied to migrant deaths. When

authorities do collect postmortem data, there are few routes by which

this information can reach families. In Europe, there is no central,

publicly accessible database cataloguing missing migrants or the

unidentified dead, nor is there significant outreach to potential next

of kin. Rather, migrants’ bodies, Robins notes, exist in a “gray zone”

of bureaucratic ambiguity, where no one is responsible for their care.

Aware of the danger of their journey, many migrants make strenuous

efforts to, in the event of their death, ensure that their bodies will

be given names. Most, like Masood, stay in close contact with family or,

lacking a phone, leave word along the way with friends. Some migrants,

if the seas become rough, inscribe their names on their T-shirts or on

the boat’s hull. Others write relatives’ telephone numbers on their life

jackets—“If found, please call.” Survivors of the shipwreck off the

island of Lampedusa, Italy, in 2013, in which 360 migrants were killed,

reported that some passengers, knowing that they would drown, shouted

out their names and the names of their villages, hoping that word would

be carried ashore.

Idomeni, Greece, 41°07’21.0″ N, 22°30’37.7″ E, a still from Traces of Exile © Tomas van Houtryve/VII

Back in Birmingham, Javed allowed

himself a week of depression over his failure in Greece before snapping

once more into action. Masood, he was forced to conclude, had lied to

him about reaching Europe. Perhaps his brother, wanting him to stop

worrying, had texted about his arrival prematurely.

Desperate for leads,

Javed revisited a mysterious note he had received from a Hungarian man,

one of the few replies to his Facebook posts about Masood. A few months

after Masood’s disappearance, the man said, he had been locked up in a

jail on the outskirts of Istanbul with one of Masood’s friends, a young

man named Tamim. He did not know the jail’s name, but he offered a

detailed description. It was a low, flat building near one of Istanbul’s

bridges. There was no sign, just a small door. Opposite the building

was a tall tree. Inside, the hallways were very dark. The prison cells,

painted black, had no beds, just carpets and blankets. Most crucially,

the Hungarian said, there were no calls allowed in the prison. Prisoners

had no way of letting anyone know they were there.

Though the story was far-fetched, Javed wondered whether Masood might

have decided to take his advice and skip the harrowing voyage to Greece

in favor of the less dangerous route through Bulgaria. There were

reports of Bulgarian authorities detaining Afghan migrants for extended

periods of time. Javed decided to visit bothTurkey and Bulgaria. The

arrangements took weeks and forced him to exhaust the last of his

savings. His girlfriend, worrying about his health—he had returned from

Greece skinnier than ever—urged him to postpone the trip, but Javed

refused. Back in Afghanistan, his parents were slowly bankrupting

themselves on fortune-tellers, who continued to insist that Masood was

alive, though they couldn’t see precisely where. While he’d once

dismissed them as haram nonsense, Javed now found their consensus

reassuring.

Finally, during the first week of January 2018, Javed landed in

Sofia, Bulgaria, where he was promptly pulled aside by customs officials

and extensively questioned. Released after midnight and unable to find a

hotel, he spent the hours until dawn wandering through the city’s gray,

Communist-era architecture. The frigid air, choked with smoke—Sofia

is among Europe’s most polluted cities—stung his lungs, and by morning

he was coughing persistently. Sucking on throat lozenges, he took a taxi

to the city’s immigration office. In the packed lobby, he waited in a

long line next to a poster for an EU program offering cash payments to

migrants if they return voluntarily to their countries of origin. Sweden

was the most generous, promising migrants up to 3,000 euros and the

cost of a plane ticket; Bulgaria, by contrast, offered just a hundred

euros as inducement to pursue “a new life” in their countries of origin.

After a long wait, a sullen police officer refused to provide any

information, because Javed lacked legal proof that he was Masood’s

brother. He got a better reception at the Afghan embassy, where a

diplomatic officer served him hot tea with honey and gently explained

that the odds that Masood had come to the country were extraordinarily

remote. By early 2016, the Bulgarian border had been effectively sealed

by aggressive policing and a long razor-wire fence. Self-described

Bulgarian migrant hunters, clad in ski masks and carrying machetes, had

taken to patrolling the forests of the Strandzha Massif, pushing back

anyone who looked like a Muslim. And if by some chance Masood had wound

up in a Bulgarian jail or refugee camp, he would have had access to a

phone.

Feeling increasingly sick and unable to stomach anything but Red

Bull, Javed bought the cheapest ticket available on a train bound for

Istanbul, an eleven-hour overnight trip. But the conductor, a

mustachioed Turkish man, saw that Javed was ill and escorted him to a

private sleeping cabin, with a Murphy bed that folded into the wall and a

little snack of crackers and apricot juice. As the train juddered

through the Bulgarian countryside, Javed, fighting a mild fever, lay on

his back and went over his plans. Turkey, he understood, would almost

certainly be his last chance to find Masood alive.

When Javed arrived in Istanbul, he hailed a taxi and asked the driver

if he knew of a jail near a bridge. There was, in fact, a men’s prison

on the eastern side of the city, not far from the Bosporus River. When

the taxi arrived at the site, Javed’s heart began to pound in his chest.

The building seemed to match the Hungarian’s description. It was low

and flat, and though there was no big tree, Javed could see a large

construction site nearby, and he reasoned that the tree could have been

chopped down. Forgetting his illness, he all but ran to the front gate,

where he was ushered inside by a sympathetic guard. For a brief moment,

as he passed though the door, Javed believed that he was on the verge of

finding Masood. This, he thought, was where his brother had been the

whole time.

Moments later, an administrator pointed out a pay phone on the wall

of the prison’s common room. Later, at the Ministry of Justice, he

learned that there were, in fact, no inmates by his brother’s name in

any of Turkey’s prisons.

His heart sinking, Javed realized that there was only one place left

for him to go: Izmir, the coastal city, from which Masood had planned to

depart for Greece. And the only place in Izmir to look, he knew, was

the morgue.

When it became clear that Masood had

failed to arrive in Greece, I expected Javed to turn his attention to

the person who had organized his brother’s trip. Mulla Kaya—the smuggler

whom Masood and his friends hired to take them to Greece—was missing,

but his associates, whom Javed had found on Facebook, lived in Istanbul.

Perhaps they could offer clues about what had gone wrong? Javed,

though, seemed uninterested in pursuing this avenue of inquiry. Nothing,

he insisted, could be learned from those men. It was better to press on

to Izmir.

I disagreed, however, and arranged, with Javed’s permission, to meet

one of Mulla Kaya’s contacts at a café on Istanbul’s massive Taksim

Square. Although it’s a public space, I had heard enough of Javed’s

stories about the depredations visited on migrants by smugglers to feel

skittish. Mulla Kaya’s associates might not appreciate someone asking

questions about their friend’s highly illegal line of work. I became

even more nervous when, at the appointed time, not one but two men

approached me. The first of them—tall and cheerful—introduced himself as

Khushal; the second—small and stone-faced—said he was Mulla Kaya’s

brother, Manaf. Both shook my hand warmly and, drawing up seats,

preceded to tell me a story remarkably similar to that of Javed and

Masood: two Afghan brothers seeking sanctuary in the EU, only for one to

abruptly disappear.

Mulla Kaya—not his real name, but a pseudonym used for his career as a

smuggler—had, they explained, lived by a Pashto proverb: “Take risks,

otherwise you risk your life.” A few years before, Mulla Kaya and Manaf,

both in their early twenties, had sought to travel from Afghanistan to

Europe, but could afford to make it only as far as Istanbul. The

brothers had taken jobs at a car wash, hoping to earn enough to complete

their trip. But after Mulla Kaya got in a fight with the owner over

unpaid wages, he decided that the best way to escape the city was to

become a “gamer”—a smuggler of people. Partnering with an established

smuggler, Mulla Kaya found the work exceedingly lucrative.

In a single

year, he was able to fill twenty boats with twenty-five migrants each.

Earning a commission of $300 per passenger, he was quickly able to send

Manaf on to Sweden. His style was daring. Unlike most smugglers, who

placed their clients in a raft and pointed them in the right direction,

Mulla Kaya kept expenses to a minimum by transporting the passengers

himself, saving him the cost of replacing the raft.

At the end of 2015, Mulla Kaya, having amassed a small fortune,

announced to his friend Khushal that he was ready to retire. The next

game, leaving in the beginning of the New Year, would be his last. When

he arrived in Greece, he planned to scuttle the boat and continue on to

Sweden. Khushal encouraged him to wait until spring: the winter weather

on the Mediterranean was unpredictable.

But Mulla Kaya was eager to

reunite with Manaf. After that, Khushal said, his phone went dead.

Then, six months later, Khushal and Manaf—who had returned to

Istanbul to search for his missing sibling—received distressing news.

On January 8—only a few days after Mulla Kaya’s boat was scheduled to

leave—the police had found a dead man, drowned, at a beach in Izmir

province. Finding a phone number in the man’s pocket, the police had,

after much delay, reached the dead man’s cousin, with whom Khushal was

friendly. The police had sent him a picture of the bloated body in a

coffin, wearing a life vest. The cousin confirmed the identity of the

dead body, a man named Mohammed.

Mohammed, he said, had gone missing in

early January while on his way to Europe. His smuggler, he recalled, had

been named Mulla Kaya.

For Khushal and Manaf, the discovery of the body was evidence enough

that Mulla Kaya’s boat had wrecked and that he was no longer alive. To

them, the matter seemed settled. They still hoped, though, that his

corpse might one day turn up, so that it could be accorded a proper

Muslim burial.

“It is always better to find the body,” Khushal told me. “Always.”

Izmir, Turkey, 38°25’32.8″ N, 27°07’55.1″ E, a still from Traces of Exile © Tomas van Houtryve/VII

I once asked Javed whether he thought

it would be worse to know for certain that his brother was dead or to

have the matter remain unresolved. He thought about this for a long

time.

“To learn that Masood was dead?” he said finally. “That’s the worst thing I can think of.”

Javed had, in fact, already heard the story of Mohammed’s body being

discovered in Izmir—had learned of it even before departing for Greece.

It seemed, given the timing, an undeniable likelihood that Masood and

Mohammed had taken the same boat to Greece, and that the boat had sunk.

Yet, Javed, it was clear, had pushed this evidence out of his mind. For

his entire search, he had refused to seriously entertain the notion of

his brother’s death. Now, in Izmir, Javed found himself approaching,

with great reluctance, a reckoning he’d dreaded and could no longer

postpone.

Yet, when we arrived at the municipal morgue, Javed encountered still

another bizarre obstacle. Normally, the morgue attendant explained, the

coroner would have records of all the unidentified bodies discovered in

the province. But in 2016, after a failed coup, Turkey’s authoritarian

president, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, had initiated a purge of thousands of

government officials suspected of being allied with the plotters. Among

them was an employee of the coroner’s office whose computer contained

information from the first six months of 2016—the period when Masood had

gone missing. Both the man and the computer had been seized by

authorities.

There was, the attendant added, one more avenue to explore. The

gendarmerie—the Turkish army’s law-enforcement arm—should have records

of any bodies found, as well as photos of the corpses. He directed Javed

to the station of a town called Menderes, ten miles south. Pale and

sweating, Javed found a taxi.

In Menderes, Javed’s request was greeted with perplexity. An officer

explained that he had been sent to the wrong place—he would need to go

to the town of Özdere, another fifteen miles to the south. Concerned by

Javed’s wan appearance, he offered to provide him a ride in a police

van. The drivers, two smooth-faced cadets in their early twenties, were

in a playful mood and spent the trip blasting Turkish techno music,

running the siren at pretty women, and using the loudspeaker to make

random announcements to the countryside. Javed stared silently out the

back window. As the van reached Özdere, the sun was setting over the

beach, which was lined with resort hotels, vacant for the winter. It was

two years to the week, Javed realized, since Masood had disappeared.

Inside the gendarmerie station, Javed was met by the commander—an

aristocratic-looking man with a powerful jaw—in full military uniform,

enthroned behind a big wooden desk. Shivering and short of breath, Javed

explained his reason for being there. “Did you find any bodies here?”

he asked, barely able to get the words out.

The commander looked confused. Gendarmerie postings rotated

frequently, and he and his troops had only arrived in Özdere during the

past year. To his knowledge, though, no body had ever been found nearby.

For a second, Javed looked like he might cry. Instead, he took out

his phone and pulled up the picture of Mohammed, in his life vest, lying

in the coffin. Inspecting it, the commander’s eyebrows rose.

“This,” he murmured, “is a Turkish coffin.”

The commander was quiet. Then he sat upright and, staring into

Javed’s eyes, declared with absolute conviction, “I will figure this

out.”

For the next two hours, Javed watched as the commander put on a

virtuosic display of police work. Copying Mohammed’s photo onto his

phone, he made a series of texts and calls, all in Turkish. Javed had no

idea what the commander was saying or doing, but he deployed a variety

of tones—authoritative, wheedling, chummy, polite—and hastily scribbled

notes on a small pad as he went, pausing only to sip from a glass of

tea.

Finally, the commander put down his phone and turned to Javed. He had the story.

On the morning of January 8, 2016, a fisherman had been walking on

the beach near Özdere when he stumbled across a dead body. It was

Mohammed. The man contacted the local gendarme, who gathered up the body

and photographed it. For several days, the police searched up and down

the coast, looking for signs of a shipwreck, but had found none. No boat

and, more significantly, no bodies.

“So there was no chance another body was found?” Javed asked.

The commander shook his head. He had asked every gendarme commander

within thirty miles. If Mohammed had been on a boat, his corpse was the

only remaining sign it had ever existed.

Javed paused. “There is no place else to look?” he finally asked.

The commander was silent.

And just like that, it was over. Javed’s search had hit its final

dead end. He stood up, shook the commander’s hand, and headed off into

the night.

As we walked outside, I was hit with a wave of despair. Javed had

come all this way, traveling thousands of miles through three countries,

had spent untold amounts of money and sweat and anguish . . . for what?

To have it confirmed that his brother could not be found? That Masood

would, despite everything, remain lost forever? It was hideously unfair.

And yet, Javed was smiling. “I thought for sure we were going to find his body,” he chuckled. “But we didn’t.”

The worst thing Javed could imagine, I realized, had not come to

pass. As long as there was no proof of Masood’s death—no photograph, no

official report, no corpse—there was still hope. The van drivers, whose

mood now nicely aligned with Javed’s, dropped us at a subway station,

where we boarded a train for our hotel.

Then, as we were sitting on the train, a strange thing happened.

Javed was in the middle of talking to me—explaining how much he

appreciated the commander’s efforts—when he was overcome by an

uncontrollable fit of coughing and sneezing. All at once, his entire

body seemed to explode with illness. By the time we got to the hotel, he

was almost too weak to move.

The next morning, I texted Javed to ask how he was doing. He had

never once answered this question from me with a response other than

“Okay.” Now, though, I received a text reading, simply, “So bad.” When I

knocked on his door, he took several minutes to open it. I found him

kneeling on the floor, supporting himself on a low end table. He

looked—there was no other word—cadaverous. The hotel desk clerk summoned

a taxi, and Javed was rushed to the hospital. But, once there, the

doctors could find little wrong with him other than a mild fever. They

prescribed an antiviral medication and sent him back to the hotel. When

Javed returned, he crawled into bed and, for several days he stayed

there, drifting in and out of consciousness.

During this delirious interlude, Javed would tell me later, his body

had felt like it was on fire. His limbs and chest had been racked with

burning pain, and he wasvisited by vivid nightmares—of Masood, of

his parents, of Afghanistan, of the Taliban. He’d never been sick like

this in his life, and it scared him. He wondered if he had done

something wrong to bring this on himself. Perhaps this was Allah

punishing him for his trust in the fortune-tellers. Or maybe he had

never been meant to visit Turkey at all.

It was hard not to see Javed’s illness as a symptom of his search,

the physical expression of an unspoken—or unspeakable—emotional state.

Failing to find Masood, or his body, denied him the right to either

celebrate or grieve. He would likely remain, for the rest of his life,

in the liminal agony to which the families of almost all missing

migrants are consigned: knowing that his brother was almost certainly

dead, but unable, once and for all, to move on.

A few days later, after recovering, Javed flew back to Birmingham. I

wondered whether, given time, he might look at the facts of the case and

be able to settle on a narrative of what had happened, as Khushal and

Manaf had. It was not the same as a resolution, but it was perhaps a

kind of peace.

Yet, when I spoke with him recently, Javed said that he was

considering looking for Masood in Syria. Afghan migrants, he had heard,

sometimes pretended to be Syrian to improve their odds of being granted

asylum. If Masood had tried that, he might have been deported to the

wrong country, where he wound up trapped in Syria’s brutal civil war.

When the war was over, Javed planned to travel there. In the meantime,

he planned to submit DNA to the Red Cross, in the hope that if Masood’s

body was somehow discovered, it might be correctly identified. He was

also considering proposing to his girlfriend. He wanted to wait,

however, to have children, until Masood came home.

And if his brother wasn’t there? I asked. If Syria turned out to be another dead end?

“I keep looking,” Javed said, incredulous. “how could i not?"

No comments:

Post a Comment