This ride was never safe and ample evidence was available from the beginning. They then compounded this folly by actually covering up incidents and destroying evidence. It appears that a decapitation was merely the final straw.

This slide should have been built with twice the investment in time and safety engineering accepted as standard. Instead they did it all with half.

The airborne problem should have seen it closed immediately before a single rider got on board. When does negligent homicide turn into premeditated homicide? Throw in a prime mover who literally lacked the engineering skills along with the disciplined ethical framework that comes with it and this is what happens.

The exact same thing happened with that building in Japan that pancaked when management overloaded the top floor and then ignored cracking...

The exact same thing happened with that building in Japan that pancaked when management overloaded the top floor and then ignored cracking...

How a Freak Accident Happens

Over two years after 10-year-old Caleb Schwab lost his life on the tallest waterslide in the world, the amusement park industry has yet to fully reckon with the tragedy.

Standing on a platform more than 168 feet high and overlooking the flat entirety of the Kansas plains, Jess Sanford was scared.

On

vacation from Lincoln, Nebraska, with her friend Melanie Gocke and her

friend’s family in August 2016, Sanford, then a rising high school

junior, didn’t know anything about Schlitterbahn Kansas City. The park,

which had been open since 2009, was the first effort outside of Texas

for Schlitterbahn, the family-run water-park dynasty that’s become the

world’s preeminent aquatic amusement giant, with its original park

winning “Best Waterpark in the World” by Amusement Today for two consecutive decades.

The

only thing Sanford, a self-proclaimed adrenaline junkie, did know on

this summer road trip was that Schlitterbahn Kansas City had an

attraction no other water park could claim: the Verrückt, the tallest

waterslide in the world. And after waiting about thirty minutes and

walking 264 steps with Gocke and Gocke’s little sister, it was Sanford’s

turn to go down the slide named “insane” in German. She wondered to

herself if the Velcro straps that held riders in place were safe enough

on a waterslide deemed by the Guinness Book of World Records two years

earlier to be the tallest in existence. In times of fear, Sanford says

she resorts to humor, which is exactly what she did with the

twenty-something lifeguard who helped strap her into the raft at the top

of Verrückt around noon that summer Sunday.

“I feel really bad about this now,” the nineteen-year-old told Esquire

about that day, “but I was joking with the lifeguard, asking her if

anyone had ever died on this thing. When she said no, I said, ‘There’s a

first for everything.’”

For the amusement-ride

thrill seeker, Verrückt was a bucket-list experience without rival.

Challenging the laws of physics, the slide presents a drop from

seventeen stories high, hitting up to sixty-five miles per hour and

often leaving people soaking wet, shaking with a mixture of raw

excitement and genuine fear. The slide won Best New Ride (WaterPark) in 2014 and was voted the fifth best water-park ride in the world in its first two years by Amusement Today.

A

couple of hours later on August 7, 2016, Scott Schwab brought his wife

and four sons to the park. A Republican state representative for nearby

Olathe, Schwab and his family had come to Schlitterbahn as part of

Elected Official Day, a promotion in which state legislators were

invited in for free. When it was time to check out Verrückt, Schwab

offered a reminder to his boys—specifically to ten-year-old Caleb, the

second oldest of his children who loved playing outside.

“Before they took off, I said, ‘Brothers stick together,’” Schwab recalled to ABC News. “And he says, ‘I know, Dad.’”

Later

that afternoon, Sanford and Gocke were hanging out at one of the picnic

tables at Boogie Bay, the final area of Schlitterbahn Kansas City’s

extensive lazy-river setup with a view of Verrückt. Not too far away,

Nathan Schwab was waiting at the bottom of the slide for his brother,

Caleb, to come down Verrückt. Caleb was in Raft B, joined by sisters

Matraca Baetz and Hannah Barnes in the seats behind him. The

ten-year-old was obeying all of the rider instructions given to him, but

the raft that was carrying Schwab, Baetz, and Barnes allegedly had “a

propensity for going abnormally fast and going airborne more frequently

than other rafts,” according to an indictment that would be filed later.

Tyler Miles, the operations manager of the park, had received seventeen

separate staff reports during the 2015 and 2016 summer seasons about

how Raft B required maintenance, including five from that week alone.

When the raft pushed off, the seventy-three-pound Schwab was in the

front seat.

Sanford was eating a funnel cake with her back to the slide when she heard a noise, almost as if a ride had derailed. She turned around to see what was happening. On its way up to the second hill of Verrückt, Raft B went airborne, colliding with a metal pole and netting meant to prevent riders from being thrown from the ride. Sanford immediately realized the fear she nervously joked about hours prior was beginning to unfold in real time.

Sanford was eating a funnel cake with her back to the slide when she heard a noise, almost as if a ride had derailed. She turned around to see what was happening. On its way up to the second hill of Verrückt, Raft B went airborne, colliding with a metal pole and netting meant to prevent riders from being thrown from the ride. Sanford immediately realized the fear she nervously joked about hours prior was beginning to unfold in real time.

“I saw my friend’s face kind of drop, and that’s

when I saw it,” Sanford said. “Because of how fast you go on that ride,

it all kind of happened in a blink.”

The

sight of a body in the water and a river of blood trickling down the

slide are images that have a permanent home in Sanford’s mind. In the

area next to the lazy river, men, women, and children stood with their

hands over their mouths, reacting to the terror that played out in

seconds on a summer day in Middle America. One little boy was screaming

for help, Sanford remembered. As Michele Schwab, Caleb's mother, tried

to get closer to see what was going on, a gentleman stopped her. “And he

just kept saying, ‘No, trust me, you don’t want to go any further,’”

she recalled.

Scott Schwab needed a definitive answer to a question he could barely bring himself to ask.

“I just need to hear you say it: Is my son dead?” Schwab reportedly

remembered asking someone at the scene. “And [the man] just shook his

head. And I said, ‘I need to hear it from you: Is he dead?’ He [said],

‘Yes, your son is dead.’”

Caleb Schwab had been decapitated. It was the final time anyone went down Verrückt.

As

people continue to try to figure out how a ten-year-old boy lost his

life going down the world’s tallest waterslide, Schlitterbahn’s

leadership, as well as the employees responsible for the ride’s upkeep,

have taken the brunt of the blame. Jeff Henry, Schlitterbahn’s co-owner,

and John Schooley, the ride’s lead designer, are facing second-degree murder charges.

Miles, the park's operations manager, is facing a charge of involuntary

manslaughter. In October, two other maintenance workers, David Hughes

and John Zalsman, were found not guilty of

lying to obstruct the investigation into Schwab’s death. In early 2017,

Schwab’s family settled with Schlitterbahn and other companies involved

in their son’s death for nearly twenty million dollars. (Baetz and Barnes, the two sisters who rode with Caleb and suffered serious facial injuries, settled with Schlitterbahn for an undisclosed amount in 2017.)

But attorneys for Schlitterbahn say the

evidence presented last spring in the Kansas attorney general's case

against the waterpark giant abused the grand jury in order to obtain

criminal indictments against Henry, Schooley, Miles, and the company. In

a January 25, 2019 court hearing, an attorney representing Henry &

Sons Construction, Schlitterbahn's general contracting affiliate, argued

that the evidence shown to the grand jurors was flimsy and inadmissable

because it included clips from a scripted show highlighting the

construction of the waterslide, the Kansas City Star reported.

(The state's assistant attorney general refuted Schlitterbahn's

suggestion that the grand jury was "too stupid to discern a television

show for evidence.")

"I believe the state's

presentation today only reinforces the validity of our arguments," said

attorney Jeff Morris on January 25. "It is almost a concession that they

screwed up. It is almost a concession that evidence they presented to

the grand jury was improper."

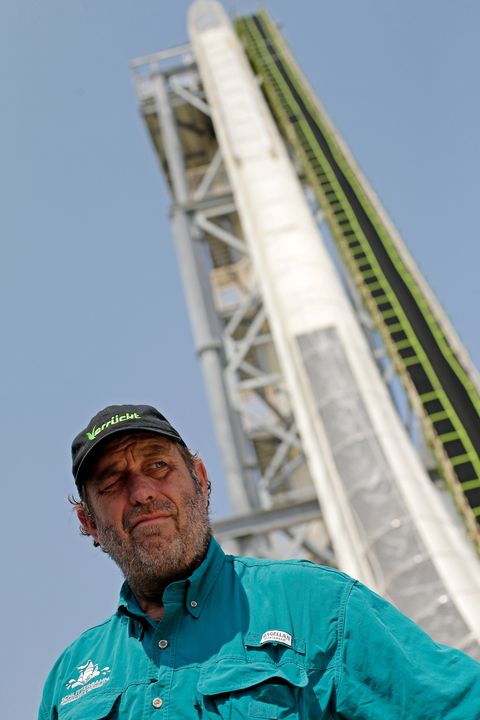

Walking

out of a Wyandotte County, Kansas, courtroom this past April,

Henry—regarded in the water-park industry as the “Wizard of Wet,” “Lord

of the Slides,” and an “aquatic Walt Disney”—was surrounded by his legal counsel, confidants, and local media. Henry entered a not guilty plea and rarely spoke during the hearing. It was his first appearance in Kansas since Schwab’s death.

A

reporter peppered Henry, who dreamed up and designed the Verrückt, with

questions that have followed the sixty-three-year-old ever since that

day in August. Are you a high school dropout? Do you have any

engineering or business background? Were you aware of the previous

injuries on Verrückt? If found guilty, Henry faces a maximum penalty of

up to 117 months—almost ten years—in prison.

In an interview published in July 2018 with Texas Monthly, Henry refused to acknowledge that he could have designed something that would eventually kill Caleb.

“I thought we had designed the biggest,

baddest thing ever built, a ride that could operate safely and never

have a serious accident, ever, if things were complied with and if the

thing was maintained and operated as designed,” Henry said. “I’m telling

you, the ride that was built by John Schooley and Jeff Henry is not the

same ride that that boy was on the day he died.”

He added, “If I really believed I was responsible for the death of that little boy, I’d kill myself right now.”

But

then how did a water-park company that embodied the American success

story, a family business that made it big, go wrong? How was the

amusement-park giant, and the people behind it, permitted to allegedly

act so negligently and irresponsibly on a project for which the stakes

were so high?

In March 2018, a forty-seven-page indictment from a

grand jury in Wyandotte County revealed, among other things,

whistle-blower evidence of how Schlitterbahn officials allegedly covered

up other safety-related incidents on Verrückt, and concluded that the

slide’s lack of safety standards “posed a substantial and unjustifiable

risk of death or severe bodily harm.” While it isn’t unique for

amusement parks to get sued for isolated incidents, the magnitude of the

Schwab tragedy, and Schlitterbahn’s decorated profile, made the grand

jury’s findings of the water park’s negligence that much more damning.

And interviews with numerous former Schlitterbahn employees and park

visitors who rode the Verrückt, together with the indictment, paint a

picture of hubris and shoddy safety standards that, when combined,

ultimately proved deadly.

“[Verrückt] could hurt me, it could kill me, it is a seriously dangerous piece of equipment today, because there are things that we don’t know about it,” Henry said during the testing of the slide. Henry later told Texas Monthly he was acting when he said those things in order to glamorize Verrückt, but at the time, he continued to glorify the ride's danger: “It’s complex, it’s fast, it’s mean. If we mess up, it could be the end. I could die going down this ride.”

“[Verrückt] could hurt me, it could kill me, it is a seriously dangerous piece of equipment today, because there are things that we don’t know about it,” Henry said during the testing of the slide. Henry later told Texas Monthly he was acting when he said those things in order to glamorize Verrückt, but at the time, he continued to glorify the ride's danger: “It’s complex, it’s fast, it’s mean. If we mess up, it could be the end. I could die going down this ride.”

Attorneys for Henry and Schooley did not

respond to multiple interview requests. Miles's attorneys declined to be

interviewed. Citing the pending litigation, Schlitterbahn was unable to

give responses to dozens of questions provided by Esquire

regarding the company, Henry, the Kansas City water park, Verrückt, its

safety procedures, and other topics. Instead, Prosapio offered a

statement.

“The Verrückt accident was a terrible and tragic event and we cannot imagine the suffering that the victims and their families have endured,” Prosapio said in an email. “As a result of the accident, there are many questions surrounding this attraction—all designed to determine what happened.” She added: “We recognize that the Verrückt accident has caused people to question the safety of other attractions; while understandable, we hope the experiences of millions of guests over the past 40 years speaks to our continued commitment to provide fun entertainment in a safe manner.”

“The Verrückt accident was a terrible and tragic event and we cannot imagine the suffering that the victims and their families have endured,” Prosapio said in an email. “As a result of the accident, there are many questions surrounding this attraction—all designed to determine what happened.” She added: “We recognize that the Verrückt accident has caused people to question the safety of other attractions; while understandable, we hope the experiences of millions of guests over the past 40 years speaks to our continued commitment to provide fun entertainment in a safe manner.”

In 1979,

years after buying Camp Landa along central Texas’s Comal River, the

Henry family purchased the property next door and rebranded the resort

into a four-slide water park. There, Schlitterbahn was born. The driving

force behind it was Henry, a high school graduate who spent one week at

college and never had any formal training in engineering. Instead of a

classroom, Henry, whose first job was sweeping his family’s resort for

twenty-five cents an hour, grew obsessed with water and its

possibilities as an engine of entertainment; by the time he was sixteen,

he’d build his first waterslide. “I learned everything I know about

water by looking at it, watching it,” Henry told author Tim O’Brien in Legends: Pioneers of the Amusement Park Industry. Since then, Schlitterbahn has become a rite of passage for anyone who’s had to bear a Texas summer.

But dominating Texas wasn’t enough for the

Henrys. In September 2005, the company announced plans for a park in

Kansas City, Kansas—its first water park outside the Lone Star State and

the fourth of five current facilities—with grandiose visions of

building the kind of towering resort with hotels, cabins, and tree

houses that would take Schlitterbahn to the next level. The blueprints

for the once-projected $750 million development made the sprawling

attraction look like something never before seen outside Disney, let

alone at a water park. In the plans, you see a destination comprising

the rides of Schlitterbahn, the culture of the San Antonio River Walk,

and the lodging of Swiss Family Robinson. The Unified

Government of Wyandotte County and Kansas City, Kansas, had already put

together an effort to convince residents to spend their recreational

dollars in Kansas instead of Missouri. The additions of Kansas Speedway,

a minor-league baseball stadium, a popular furniture store, a Cabela’s

store, and an outlet mall showed the area’s commitment. Schlitterbahn’s

arrival was meant to be the final piece of the border puzzle.

During

an October 2007 state legislature hearing, Kansas lawmakers pressed

Mike Hutfles, a lobbyist with Schlitterbahn, on whether the company

would be opposed to pursuing a requirement for safety inspections.

Though Hutfles said he had “no problem” with it, he said the company

preferred to be granted a “Disney exception,” a clause Schlitterbahn had

been operating under in Texas that allows for “company inspection, in

conjunction with the state.”

The exception essentially gave Schlitterbahn

the right to self-regulate its safety and maintenance standards without

strict oversight from the state. Tom Sloan, a former twelve-term

Republican state representative out of Lawrence who pushed for revised

legislation on amusement-park safety in 1999 and 2001, saw firsthand how

the money promised to the area coupled with the lacking oversight was

going to make it easy for Schlitterbahn to get green-lit.

“They

were prepared to make a very substantial financial investment in the

state of Kansas, and that always gets legislators’ attention,” Sloan

told Esquire of Schlitterbahn. “There was a very strong

majority of legislators from that part of the state who said

Schlitterbahn would be responsible for their own safety measures.”

He added: “Schlitterbahn was basically hanging their hat on the Disney language—‘We are so big that we can self-inspect.’”

The initial financial boon promised by the Texas water park’s arrival failed to be fully realized. The financial crisis of 2008 caused priorities to shift in many areas, including the amusement-park industry. After delays forced the park into a soft opening in 2009 and a full-season opening in 2010, Schlitterbahn Kansas City, without any of the lodging originally envisioned, was labeled as a $180 million investment, missing the initial projection by more than three-quarters of the value. “The park had a lot of promise, but also a lot of issues,” said an industry veteran who has developed water-park rides throughout the world, including with Henry and Schooley at Schlitterbahn Kansas City. The industry veteran, who requested that Esquire withhold their name, laid out how the size of the park’s site, the timeline on their land and development goals, and the sweltering Kansas heat made the project one that was constantly reeling. “It never really came together for me,” the expert said.3

The initial financial boon promised by the Texas water park’s arrival failed to be fully realized. The financial crisis of 2008 caused priorities to shift in many areas, including the amusement-park industry. After delays forced the park into a soft opening in 2009 and a full-season opening in 2010, Schlitterbahn Kansas City, without any of the lodging originally envisioned, was labeled as a $180 million investment, missing the initial projection by more than three-quarters of the value. “The park had a lot of promise, but also a lot of issues,” said an industry veteran who has developed water-park rides throughout the world, including with Henry and Schooley at Schlitterbahn Kansas City. The industry veteran, who requested that Esquire withhold their name, laid out how the size of the park’s site, the timeline on their land and development goals, and the sweltering Kansas heat made the project one that was constantly reeling. “It never really came together for me,” the expert said.3

By most accounts, Henry’s Schlitterbahn

Kansas City was an above-average park in its first few years, but it was

underwhelming compared to what was promised. Henry wanted to change

that. On November 13, 2012, he was at a trade show when he was

approached by producers from the Travel Channel who were working on a

new show that looked at some of the most incredible water parks and

water attractions in the world. What unfolded next could be viewed today

as an instance of Henry’s obsession with being the best.

“I always set out to break all the records,” he reportedly told USA Today.

“I want to be the first at the bar to buy a drink and I want to be the

first to meet a pretty girl and I want to be the first at everything.”

That

meant having a ride at Schlitterbahn that no one had seen before,

specifically at the only park outside of Texas that was still trying to

make a splash. In a bid to impress the producers, Henry told them he was

building the biggest, tallest, and fastest waterslide in the world.

“I said, ‘It’s a speed blaster.’ Well, it didn’t exist. The concept didn’t exist. I just made it up on the spot,” Henry recalled

to Grantland. “And then I came back and told my brother and sister. I

said, ‘Mmmm, I just announced this major new ride.’” Steven Tyson, his

assistant at the time, added: “He wasn’t the tallest and he wasn’t the

fastest, so he decided to make that happen.”

Schooley would recall to Gizmodo in July 2014 their reasoning for building Verrückt: “Basically, we were crazy enough to try anything.”

Now a waterslide taller than Niagara Falls had to be completed seven months later.

Seemingly

from the jump, Verrückt was built in haste, with Henry pushing the

timetable. With June 15, 2013, set as the deadline for the entire

project, Henry and Schooley had put themselves in a tight spot. On

December 14, 2012, Henry wrote

an email to the seventy-three-year-old Schooley and others: “We all

need to circle on this,” he wrote. “I must communicate reality to all.

Time, is of the essence. No time to die. J[.]” He followed up that same

day: “I have to micro manage this. NOW. This is a designed product for

TV, absolutely cannot be anything else. Speed is 100% required. A floor a

day. Tough schedule. Jeff[.]”

What would usually take three to six months

in design calculations was completed a little more than five weeks after

Verrückt was first conceived. As the testing unfolded, one common

denominator was present: The rafts kept going airborne. “I was pretty

shocked to see the approach they took when designing, building, and

maintaining the Verrückt,” said Deborah Hersman, former president and

CEO of the National Safety Council. “That is absolutely not what we

would expect.”

Delays would creep in and cause a massive

redesign that would stretch into 2014. The ride was simply too fast. The

magnitude of the project was not lost on at least one installer who had

worked on fifteen to twenty projects for Schlitterbahn as part of Henry

& Sons Construction, the general contractor owned by Henry that was

put in charge of building Verrückt. The construction employee, who

compared their projects for Schlitterbahn to “working for Disneyland,”

said that while modifying the slide wasn’t intimidating, it was

certainly exhausting.

“This kind of project had never been done before,” the construction employee said. “We literally worked around the clock.”

“This kind of project had never been done before,” the construction employee said. “We literally worked around the clock.”

By April 2014, the Guinness Book of World Records officially declared Verrückt the world’s tallest waterslide, despite it not being close to finished.

“If

we actually knew how to do this, and it could be done that easily, it

wouldn’t be that spectacular,” Schooley said at the time, according to

the indictment.

A former lifeguard who spoke with Esquire

saw firsthand the issues with not just the record-breaking slide, but

also the work culture at the Kansas City park. The lifeguard, who spent

four summers at Schlitterbahn Kansas City between 2011 and 2014,

recounted an unstable work environment where misbehaving, immature, and

inexperienced employees were kept on to fill the park’s lifeguard quota,

while adequate water and bathroom breaks were not always a given in the

stifling summer days. During the former employee’s final summer in

2014, the one in which Verrückt was set to open, the lifeguard

remembered how Schlitterbahn tended to do the test runs after the park

closed at 6 p.m., away from the public. The lifeguard also said that

Schlitterbahn had only a select group of more experienced employees

present for the slide’s testing. (Winter Prosapio, Schlitterbahn’s

spokesperson, declined to comment on all of the above due to pending

litigation.)

“The only time I saw the slide run

successfully was on the Travel Channel episode, but I wouldn’t even call

that successful,” said the lifeguard, who was part of a select group of

employees present for the taping after the park closed that day. “When

they went down, the Travel Channel folks got stuck on the second hump,

so they had to do a rerun.” The former employee added: “After seeing

that, I told my friends and family it was only a matter of time until

someone died on Verrückt. What made me say that was that the sandbags

that were being tested kept flying off the rafts.” (The anecdote was corroborated in the reporting from the July story in Texas Monthly.)

By the time the episode of Xtreme Waterparks first aired on June 29, 2014,

the slide had yet to open. Today, all archives of the episode and

mentions of Verrückt have been scrubbed from the Travel Channel’s

records, and the episode is no longer available on streaming services.

(The show’s executive producers did not respond to multiple interview

requests.)

Media reports leading up to Verrückt’s opening touched on the ride’s age limit of fourteen, which, according to the indictment,

the slide’s designers decided on after a consultant had recommended the

age be sixteen. (The same consultant would later advise Henry that the

ride was unfinished and unsafe.) Yet, on the eve of the grand opening,

for reasons that remain unclear, the imposed age restriction was

eliminated, ultimately allowing younger kids, such as Caleb Schwab, to

ride Verrückt.

When the time came to finally open the slide

in July 2014, the hype had hit a fever pitch, with favorable headlines

and print, TV, and video pieces coming from the likes of the Today show, ABC News, USA Today, Grantland, the Kansas City Star,

and others. In addressing the viral videos of the sandbags flying off

the testing of the ride, Henry expressed confidence that the ride was

good to go. “It’s dangerous, but it’s a safe dangerous now,” Henry told USA Today in the lead-up to the opening. “Schlitterbahn is a family waterpark, but this isn’t a family ride.”

On

July 10, 2014, the slide opened to the public. Local officials, media,

and even Kansas governor Sam Brownback came to take part in the first

rides. (Brownback, now the U.S. ambassador for International Religious

Freedom, declined to be interviewed.) “I saw the sandbags fly out of the

boat and I still went down it,” Wyandotte County District judge

Kathleen Lynch told Esquire, who added that she estimated she rode Verrückt more than ten times. “It was just exhilarating.”

It was a sentiment echoed by the construction

employee, who, after loading the one-hundred-ten-pound sandbags into the

rafts for hundreds of test runs, said that he or she “wasn’t leaving

Kansas until I ride this thing.” “I rode it damn near twenty times in a

day and a half,” said the installer, who added that the ride, which felt

like “a freaking freight train,” did not feel unsafe. “That should tell

you something about how I felt about it.”

While Henry and Schooley stood on an elevated

platform between the slide’s main descent and second hill that day the

slide opened, they watched as a raft lifted riders over the crest of

Verrückt’s second hill. Henry noticed something.

“Man,

are they hitting that net up there?” Henry asked Schooley, according to

the indictment. “That boat flew. That boat looked like it flew.”

When

Raul Dueñas returned to Schlitterbahn for the first time since moving

back to Kansas City from California, he thought Verrückt was too high.

On July 24, 2016, Dueñas, who had made multiple trips to Schlitterbahn’s

parks in Kansas City and South Padre Island, Texas, visited the water

park with his friend, son, then-wife, and her family. But before the

park closed for the day, the forty-one-year-old wanted to ride the slide

he had heard so much about.

Dueñas and his

friend were egging on his son, Jeffrey, then eleven years old, to join

them, but Jeffrey was scared. When the group was over the weight limit,

Jeffrey was relieved that he had an excuse not to go down Verrückt and

hopped out of line. But even with bad knees, nothing was stopping the

struggling Dueñas from getting to the top. Holding on to a waterproof

camera with his right hand, Dueñas warily looked on at the Velcro

straps, but there was no time to think about it. As soon as his raft hit

that first drop, the velocity of the fall caused Dueñas’s strap to come

flying off. He grabbed the auxiliary straps on the side to get him

ready for the second hump.

“I think just the excitement of the ride itself drowned out the frightening part of the straps coming off,” Dueñas told Esquire.

“It came off and I was like, Whoa, kind of grabbing a hold of the

straps and trying to hold myself down.” He added: “I told the lifeguard

that the strap came off, and the only words he could say were, ‘I would

have crapped my pants.’”

As Dueñas and his group

were leaving the park, he ran into the man who had gone in the raft

ahead of him. When Dueñas asked the man how he liked Verrückt, Dueñas

said the man told him his strap had also fallen off during his ride.

That same summer, Sara Egan and her fiancé

visited the park on a day when law enforcement, first responders, and

veterans got in for free. Egan, a twenty-four-year-old detention officer

for a local police department, remembered how she immediately felt

herself lifting off the raft. Seeing that, her fiancé wrapped his ankles

around her, and Egan anxiously held on to his legs. But that wasn’t the

only thing that unsettled her.

“The whole time

you’re going down, you can see the net above you where people or the

raft had hit it before,” Egan said. “It’s all over the damn thing. You

could tell where people hit it. I didn’t feel secure.”

Neither

Egan nor Dueñas has been back since, but Dueñas said he isn’t opposed

to it. He would, however, be more cautious given what happened at the

park two weeks after he went and how he urged his son, not much older

than Schwab, to ride Verrückt.

He said, “It’s always on my mind: What if Jeffrey got on there?”

According

to the March indictment, at least thirteen nonfatal injuries suffered

by guests who rode Verrückt were recorded in the 182 days the ride was

open between 2014 and 2016, up to and including the day of Caleb’s

death. Other injuries were reportedly either covered up or never

recorded; ride malfunctions were allegedly not properly addressed.

Within a year, fourteen- and fifteen-year-olds

suffered concussions. Brittany Hawkins, a twenty-year-old who had

previously worked at the park as a lifeguard, had her strap come undone

and came within inches of hoops and netting after her raft went

airborne. She suffered slipped spinal disks, an injury that’s left her

with chronic back pain. (Miles, the twenty-nine-year-old operations

manager, took her incident report, which is now allegedly missing from

Schlitterbahn’s records.)

Samantha Soper's head was whipped side to

side like that of a rag doll on a raft that had been repaired with duct

tape, causing the twenty-three-year-old to suffer from severe neck pain.

Donald Slaughter’s raft collided with a concrete wall, resulting in

herniated spinal disks and radiating numbness and tingling in the

forty-two-year-old’s right arm.

Another

instance involved a man who identified himself as the designer of the

slide, whom prosecutors strongly believed was Henry: He allegedly

bragged to Richard Palmer, a forty-two-year-old who was seeking medical

assistance after breaking his toes on the slide, about his achievements

and how he wanted to build a ride taller than the Verrückt.

On

June 16, 2016, Norris “JJ” Groves, the owner of a towing company in

neighboring Missouri, rode Verrückt with his wife and son, according to

the indictment. When their raft went airborne at the second hill,

Groves’s face and forehead smashed into an overhead hoop and safety

netting before the raft hit a concrete wall. Rushing over to them, the

lifeguards at the bottom of the slide saw Groves’s right eye was swollen

shut, as well as other abrasions and bruising along his body, and told

them that the raft went way too fast. Once the forty-six-year-old Groves

gave his incident report, Miles allegedly destroyed the witness

statements and “forced the lifeguards to write coached statements which

omitted any detail of how the injury had occurred,” telling the medical

staff to alter their own reports. One of the lifeguards would later come

forward to a detective, revealing Miles’s work in covering up the

incident—an effort that was corroborated by members of the medical

staff. Soon, Derek MacKay, an attorney representing Schlitterbahn,

allegedly showed up to the lifeguard’s home and would later lie to both

the lifeguard’s mother and the detective in an attempt to get a copy of

the police report.

Even with the investigation into

Schlitterbahn and Verrückt, and the larger questions surrounding safety

regulation and oversight within the amusement-park industry, experts and

lobbyists say that most rides are safe enough.

In 2016, the most recent year from which data is available, 384 million guests experienced 1.7 billion rides at four hundred U.S. amusement parks without injury, according to the International Association of Amusement Parks and Attractions (IAAPA), the world’s largest trade association representing the global attractions industry. Based on a three-year average of the most recent data, “the chance of being seriously injured on a fixed-site ride at a U.S. amusement park is one in seventeen million,” said Susan Storey, IAAPA’s director of communications. Storey added: “The industry’s long-standing safety record exists because safety is our top priority.”

In 2016, the most recent year from which data is available, 384 million guests experienced 1.7 billion rides at four hundred U.S. amusement parks without injury, according to the International Association of Amusement Parks and Attractions (IAAPA), the world’s largest trade association representing the global attractions industry. Based on a three-year average of the most recent data, “the chance of being seriously injured on a fixed-site ride at a U.S. amusement park is one in seventeen million,” said Susan Storey, IAAPA’s director of communications. Storey added: “The industry’s long-standing safety record exists because safety is our top priority.”

A safety expert who’s worked with Schooley and

Henry says allegations of misconduct are baffling. “Knowing what I know

about Jeff and John, I guarantee you those guys wouldn’t put a ride into

operation that has a risk of danger,” said the expert, who preferred

not to be named due to past work with Henry and Schooley. “Safety is

absolutely paramount to them. Not reporting injuries makes no sense to

me. Why would you ever do that?”

What started

out as a freak accident has turned into a broader conversation about

what it’s going to take for the amusement-park industry, which prides

itself on its safety record and confidence to self-regulate, to prevent

another Verrückt and Caleb Schwab–level tragedy. For decades, amusement

parks have been exempt from federal regulation, leaving in charge state governments, such as Kansas, that offer little, if any, oversight.

In April 2017, the Kansas legislature, following an impassioned speech from Caleb’s father, strengthened a law on amusement-ride inspections

that previously allowed amusement-park operators to not share private

inspections with state officials, giving the state one of the weakest

sets of regulations nationwide. While the amusement-park industry

continues to have a stronger safety record compared to many everyday

activities, what makes the case in Kansas City different is an alleged

criminal element at the heart of a fatality. “We’re talking about a

child who was decapitated. That’s negligent homicide,” said Ken Martin, a

nationally recognized amusement-ride inspector and safety analyst since

1993. “You can’t blame anyone else except Schlitterbahn and the people

who put this slide together. As far as I’m concerned, they should be in

jail for the rest of their lives.” Of course, a jury will decide whether

they will be.

The trial for Henry, Schooley, and Miles,

which was scheduled to begin on September 10, has been delayed, with no

new date set. Henry is also facing separate charges

for drug possession, including a felony count of possessing

methamphetamine with the intent to distribute, and hiring someone for

sex. In July, a court granted Schlitterbahn permission to tear down Verrückt, which is now complete.

Even

with the slide finally down, a community that once looked to

Schlitterbahn as a summer refuge remains shaken and searching for

answers of what went wrong. “You feel nauseous driving around it,” said

Chris Kamler, a forty-six-year-old resident who worked across the

highway from the water park when the slide was still standing. From the

ninth floor of his office, staring at Verrückt was once inescapable: “It

[stood] as a monument to a murder.”

Today

Verrückt, the one-time eyesore on Interstate 435 and, ultimately, a sad

symbol of hubris, hardship, and a horrific tragedy that could have been

avoided, is gone.

This July I visited

Schlitterbahn on the kind of blistering ninety-five-degree July day when

you could easily bake chocolate chip cookies if you left the dough out

in the sun. I stared at the white waterslide once described by Henry as

an “erotic piece of art”—its curves and drops were as grand and

ambitious as advertised. But whatever legend the slide was building had

been boarded up at eye level, with wood panels blocking the splash site

where Schwab was supposed to come down safely. Aside from the steady

soundtrack of Bon Jovi, Taylor Swift, and Justin Bieber, Schlitterbahn

was eerily quiet from my float on Boogie Bay.

But

the people who did float would share a pause, head shake, or murmur to

look at the slide before returning to their conversations. Minuscule

smatterings of people, mostly families and high schoolers on summer

break, bounced from the rides and attractions that were still open. Four

rides at the water park remained closed

after regulators found that Schlitterbahn did not comply with new

legislation implemented in response to Schwab’s death. Walking back to

the oversized and empty gift store, I became painfully aware of the lack

of upkeep on the park’s former crown jewel. The poles holding the

structure up were rusted, and the paint was chipping away. The canopy at

the top of the ride was long gone. A lone cherry-wood fence and rope

blocked off the attraction from the public, with a sign reading, “THIS

ATTRACTION IS CLOSED.”

Days before Schlitterbahn announced it would

tear down the ride, I asked a lifeguard what the current staff tells him

and his colleagues about Verrückt. “They don’t even talk about it

anymore, really,” the young employee said to me, almost embarrassed.

“It’s still here, and it’s been two years.”

Schlitterbahn’s future also remains

uncertain. Though its two highest attended parks, New Braunfels and

Galveston, remained in the top ten for U.S. water-park attendance last

year, they were both down 3 percent each

from their 2016 attendance. In the spring of 2018, Schlitterbahn’s park

in Corpus Christi was sold at a bankruptcy auction after a company run

by the Henry brothers accrued thirty-two million dollars

in unexplained cost overruns to run the facility. But the biggest

domino to fall could be in Kansas City. In April, EPR Properties, a

Kansas real estate investment trust that holds the mortgage on

Schlitterbahn Kansas City, warned investors that the criminal

indictments might hurt the company’s chances

of paying back the $174.3 million on its loan. The trust said that if

the company defaults on its Kansas City mortgage, then the loan would

either be restructured or EPR could even foreclose on Schlitterbahn’s

collateral that got the loan in the first place. The collateral?

Schlitterbahn’s flagship in New Braunfels, as well as its parks in

Kansas City and South Padre Island.

David Alvey, the current mayor of Kansas City, Kansas, told KSHB

that he still thinks Schlitterbahn has been a good investment for the

area. “If General Motors has a fatality, would we say that was a bad

investment?” he said.

It’s a sentiment echoed by

Mike Taylor, the public relations director for the Unified Government

of Wyandotte County and Kansas City, Kansas.

“Schlitterbahn is an important tourist attraction in our community, and we hope it remains open and a success,” Taylor told Esquire.

As

of now, it is unclear whether the park will open for the 2019

season—season passes were made available for Schlitterbahn's four Texas

locations earlier this month, but not for Kansas City. "We don't have

any news so far about our Kansas City park at the time," Prosapio told the Kansas City Star.

In

plot A373 under a shady tree at Pleasant Valley Cemetery, fresh

flowers, a pinwheel, and a worn Kansas City Royals flag waves next to a

headstone featuring Caleb Schwab’s smiling face. Considering his love of

sports and that his go-to question, “Can I go play?,” is engraved on

his grave, it’s comforting to see Schwab’s resting place close to the

slides and basketball hoops at Heritage Christian Academy. On the back

of his headstone is another image of Caleb wearing the cap from his

youth baseball team, the Kansas City Mudcats. “You mention his name and

the kids say, ‘I know who Caleb is,’” Kurt Dunn, coach of the Mudcats,

told Esquire, adding that the organization retired Caleb’s No. 3.

One by one, people visiting their spouses or

children at the Overland Park cemetery come by the back corner of the

burial ground to chat with me about anything, mainly the oppressive

heat, their loved ones, and Caleb. “I tell Barry to say hi to Caleb,”

Sharon Fritz, sitting in her St. Louis Cardinals lawn chair, said of her

husband. “I like to think they’re pals up there.”

Scott Schwab—who was elected Kansas’s Secretary of State—declined to be interviewed. He did, however, grant an interview to a local Fox affiliate several months after the second anniversary of Caleb’s death.

“I

had a lot of memories I just wasn’t able to remember because I wasn’t

able to cope with memories. And now that it’s been two years, things are

coming back,” he said. “There’s a hole in our family, and we’re

learning to live with that.”

A humid breeze

presses down on the dead summer grass. There are two Bible verses on the

back of Caleb’s headstone. One is a line from John 3:16. The other is

James 4:14. You read it quietly and are reminded again that Caleb Schwab

should still be here.

For what is your life? It is even a vapor that appears for a little time and then vanishes away.

No comments:

Post a Comment