Here is an effort to deal with the fake news MEME. It is not good of course. The practise has always been with us, I am sorry to say. The problem today is that it has become easy to impliment and exploit.

Back in the day, a PR firm could have put about critical news stories describing the health dangers of butter. Once that had been accepted, it was then easy to put about stories pitching margerine. All this reconditioned the market to demand the use of margerine. It is still an exercise in both scientific and jounalistic fraud.

Seventy years on it is business as usual and most famously applied to politics. The easy commercial fruit has been picked and there you see a lot of defensive work using the same tools.

Something needs to be done and what is been done fails as well when extreme polarization is been promoted. They are now all lying.. .

Identifying Fake News in the Time of the Presidential Election – Ultimate Guide to Avoid Panic and Indifference

Sharon Hurley Hall

September 17, 2020

https://www.websiteplanet.com/blog/fake-news-and-digital-marketing/

In the last three years, there’s been a rampant increase in reports of the use of digital marketing tools like social media to spread false information, commonly referred to as “fake news.” From the supposed deaths of many celebrities (like the Cher story below) to election tampering, it seems that this trend is – unfortunately – here to stay.

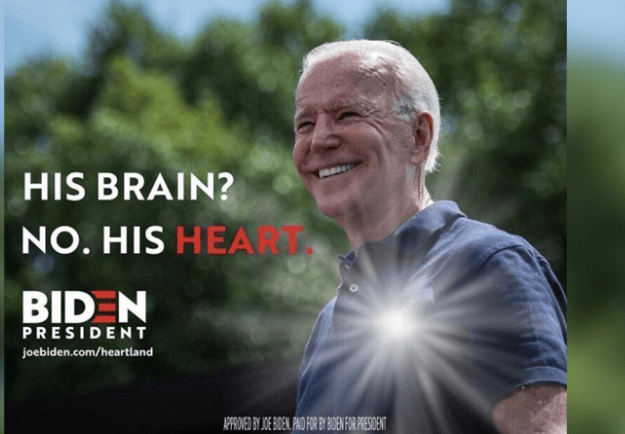

This is a particularly dangerous trend in the era of the Presidential election. It’s often difficult to know candidates’ true motive, actual voter turnout, what concerns matter people the most. For example, one popular fake news story came from a Tweet that led people to believe that despite the fact that Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden has dementia, we should still vote for him anyway, because he has heart.

But the more people talk about fake news, the less clear it is what exactly fake news entails, and how it actually spreads.

In this guide, we delve into the fake news phenomenon. You’ll learn:

The definition and types of fake news

The history of fake news

How fake news spreads

The psychology of fake news

Fake news statistics

Fake news in different digital marketing genres

Where you’re likely to find fake news

How to recognize and report fake news

We’ll also look at the top fake news websites, and assess the future of fake news.

Fake News in the Time of Corona

From fake cures to useless products, fake news about Covid-19 is spreading fast. Amazon has already deleted more than a million items deemed to be false advertising or price gouging.

The problem is, it’s not just a case of misinformation, but literally a matter of life or death. For example, the “miracle mineral supplement” contains a type of bleach and has serious side effects. And drinking alcohol to slow the virus, as some did in Iran, only results in alcohol poisoning.

To know how to handle the coronavirus, it’s more important than ever to be able to weed out reliable information (likely provided by your local health authority) from the fake stories that are rife on social media.

Fake News Defined (and Key Terminology)

A good place to start is with the definition of fake news. However, it turns out that there are almost as many fake news definitions as fake news stories. (Just kidding, but you’ll see what I mean.)

The OECD Forum Network defines fake news as:

“journalism or information that either deliberately or unintentionally misleads people and distorts reality by spreading false information, hoaxes, propaganda, or misrepresentation of facts”

The Cambridge Dictionary’s fake news definition is:

“false stories that appear to be news, spread on the internet or using other media, usually created to influence political views or as a joke”

And Projekt Neptun defines fake news as:

“the distribution of false or questionable information that is either completely invented or sold as factually correct news”

Common elements are that the information is presented as news, that it’s false, and that it’s often widely distributed via social media.

Fake News Glossary

While fake news is a fairly common term these days, there are a bunch of other terms that refer to the same – or similar – issue. Here’s a breakdown of the most common offenders:

Disinformation – false information meant to deceive or mislead, sometimes spread via the media as a government tactic

Misinformation – false information, sometimes intended to mislead

Propaganda – biased information which promotes a particular viewpoint

Clickbait – content or headlines created to get attention and win clicks, but which may have little substance and may be misleading

Computational propaganda – the use of bots to manipulate public opinion via social networks

Post-truth – relating to or denoting circumstances in which objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion and personal belief

Filter bubble – referring to the situation where web users only get information that reinforce the views they already have

Deepfake – the use of AI technology to make or alter images or videos to show something that didn’t happen (an example is the Dali Lives exhibition by the Dali Museum in Florida, which brought the deceased artist back to life)

Types of Fake News

In addition to the terms above, Digital Marketing Philippines divides fake news into five categories:

Satire or parody – this is intended to be humorous, but sometimes people share these stories as if they are real

Misleading news used in the wrong context – this is where some facts are omitted, leading to a skewed view of what’s happened

Sloppy reporting to achieve a certain agenda – similar to the above, and may result in clickbait headlines

Misleading news based on popular narrative, not on facts – this can include urban myths

Intentionally deceptive – true fake news as defined earlier

History and Rise of Fake News

Although people are talking about fake news a lot now, it turns out that fake news really isn’t all that new. The UC Santa Barbara Center for Information Technology and Society (CITS) says that fake news has been around for centuries.

Once the printing press was developed in the mid-15th century, information could be widely dispersed. That meant any organization that could benefit from pushing a particular perspective or agenda could start spreading misinformation, disinformation, and fake news.

Fast forward to the late 19th century, when technology became the catalyst for the next era of fake news. While people had been publishing newspapers for quite a while, the development of automatic typesetting and advances in communication technology made wider, faster circulation of information possible. But some of that information was definitely misleading.

Tabloid Journalism Grabs the Headlines

During this time, some papers would publish fake information just to win the headlines and attract readers (a bit like clickbait today). This was known as yellow journalism. In fact, there was a famous rivalry between US publishers Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst in the 1890s, which is thought to have led the US into the Spanish-American War.

While eventually, there was some backlash as people started wanting more reliable and dependable news stories, the headline-grabbing trend never fully went away. Tabloid journalism like that published by the National Enquirer in the US (shown below) and papers like the now-defunct News of the World in the UK have continued to be popular.

At this point, most people recognized sensationalism when they saw it. But that was to change as further advances in technology began to play a role in the spread of fake news.

Fake News in the 21st Century

Fake news is often associated with the 45th President of the United States, Donald Trump. Indeed, he has often claimed to have invented the term.

In fact, it turns out that the person who invented and popularized the term “fake news” was Buzzfeed editor Craig Silverman. He started using the term in 2014 when he was running a research project on websites that spread unverified rumors but were designed to look like real news sites, and continued using it when he moved to Buzzfeed.

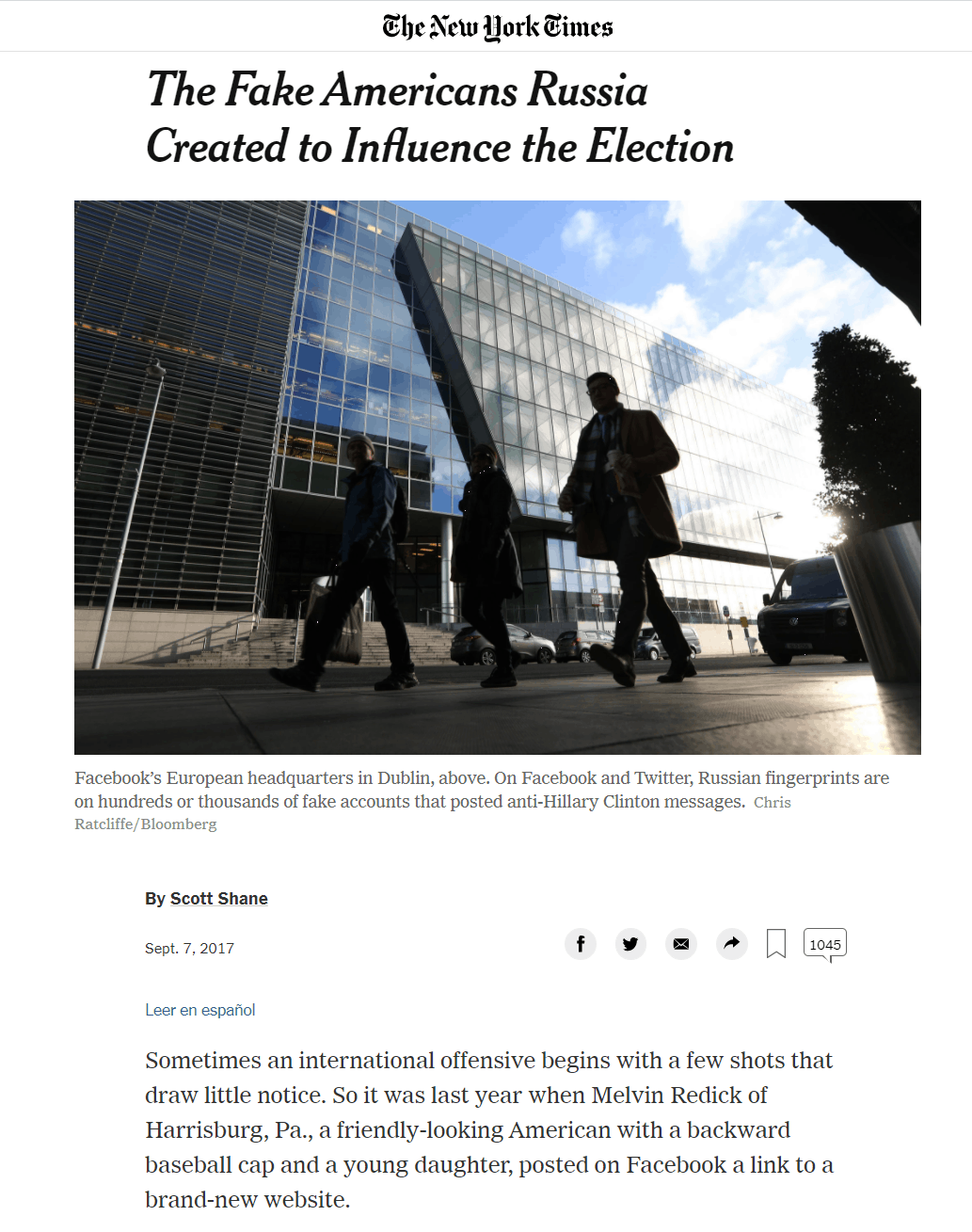

Coverage of fake news became more frequent with the 2016 US election. Subsequent to that election, it’s come out that Russian bots may have had a hand in popularizing anti-Clinton news stories and, therefore, directly leading to the election of Donald Trump.

But this is not a problem that is unique to the US There’s a fear that elections across the globe have fallen prey to the same phenomenon.

As the US election interference story began to evolve, search for the term “fake news” peaked in 2017.

It’s now in common use, with an updated definition added to the Oxford English Dictionary in 2019. People are even making fake news generators to help people create their own false news stories. While they are intended to be a bit of fun, they have helped spread fake news.

More recently, there’s been another twist. In addition to the accepted definitions of fake news, there’s a trend to dismiss any story that doesn’t match a person’s worldview as fake news, whether it’s factually true or not. As the BBC points out:

“All sorts of things – misinformation, spin, conspiracy theories, mistakes, and reporting that people just don’t like – have been rolled into it.“

While there are some stories that cross the globe, there are also those for particular localities. In Switzerland, a rumor spread via WhatsApp that hospitals were overloaded and people with Covid-19 were in beds in the hospital hallways.

In Africa, there are fake news stories about using Dettol or shaving your beard to fight the virus. In Italy, fake news about a lemon juice cure supposedly originating in China was shared more than 30,000 times. In India, a YouTube video about the origins of the virus (wrongfully claiming it originated from seafood) was viewed almost 5 million times.

In a global information society, and with a global pandemic, people are searching for information wherever they can find it. This type of fake news has the potential to stop people from taking the action that’s actually proven to work, while they focus on untested and unproven information.

Fake News: What’s Changed

We’ve seen the history of fake news and some of the terms that have been used to describe it over the centuries. But in the 21st century, fake news looks a little different from those early iterations.

Here’s a look at some of the key differences today:

There are ideological interests in spreading fake news rather than simply tabloid journalists looking to sell papers. Several countries, including Russia, have been implicated in different misinformation campaigns.

This distortion of news is done with the deliberate intent to deceive.

It’s not always clear when a story is satire or fake because the way the stories are presented has evolved to fit seamlessly into social media spaces.

Social media aggregation (rather than printed or online publications) is a key mechanism for spreading fake news.

The spread of fake news is amplified by social media algorithms (more on that later) and social media fan and follower networks.

Fake news has become increasingly difficult to discern as reputable publications try to get more attention online, using tactics like clickbait headlines to make content more appealing and more likely to go viral.

This results in a situation where digital misinformation – yet another term for fake news – is a huge threat. As you’ll see, the latest fake news statistics show just how huge the problem has become.

Fake News Statistics

The latest fake news statistics reveal two main problems. First, fake news spreads insanely quickly. And second, it’s not always easy to identify fake news. The proliferation of coronavirus fake news stories, which are quickly shared, are proof of this. According to JSTOR, around 62% of adults in the US get their news on social media sites. And many report that they believe fake news stories.

A study cited on Mobile Marketing in early 2019 shows that almost one-third of adults with a social media account have seen something they consider to be fake news within the past week. That percentage rises to 51% over a three-month period.

People read headlines and think they are getting reliable information. But although 97% of people think they can easily spot fake news stories, a recent study suggests that fake news can be more difficult to identify than people think.

While fake news crosses political affiliations, Facebook is seen as the site where fake news is most prevalent. Some 70% of people said they had seen fake news on Facebook during the previous month. That compares with 54% on Twitter, 47% on YouTube, 43% on Reddit, and 40% on Instagram.

A big issue with fake news is its virality. Fake news can be more widely shared than real news on platforms like Facebook. And an MIT study shows that fake news spreads faster on Twitter than real news. On that platform, real news takes six times longer to spread than fake news.

The same MIT study shows that humans are more likely to spread fake news than bots. But as we’ll see, machines also have a huge role in the spread of fake news.

How Fake News Spreads

So how is it that fake news is able to spread so quickly? Senior Fellow at the George Washington University Center for Cyber & Homeland Security Kalev Leetaru believes that we have turned over information gatekeeping to machines and algorithms, trusting them blindly even though we shouldn’t.

Instead of looking for information ourselves, we accept what we are fed and that’s a big danger. As Leetaru points out:

“These social media algorithms are optimized for virality and addictiveness, rather than truthfulness and evidentiary reporting. The more emotional, fact-free, and false a post is, the more likely it is to be pushed viral by these algorithms.”

But there’s also another factor. Once the algorithms surface the stories to be shared, it only takes a few people to make them go viral. For example, during the 2016 US election, a Futurity study found that 0.1% of Twitter users (super sharers) are responsible for sharing the majority of fake news. And 1% of Twitter users (super consumers) were exposed to 80% of said fake news. Since the majority of us are all hyper-connected, this amplifies the reach of the stories.

Research published on Science Advances shows that over-65 year olds spread more fake news on Facebook than younger users. This holds true regardless of gender, ethnicity, income, education, or political affiliation. While the study did not say why this is the case, it suggested that lower digital literacy skills among older users and the effect of aging on memory could be factors in this trend.

Where Fake News Comes From

Who are these people spreading fake news, and where does it come from? An IEEE report found that fake news generally originates from less popular or less known websites or media outlets, and tends to be spread more by unverified social media users.

Other fake news may be carefully selected old news on topics known to be divisive, or something that’s true or real but is published in the wrong context. There’s always someone who hasn’t heard the news before, and who’s likely to spread it.

Apart from the human spreaders of fake news, there are also the artificial originators of that news. A University of Oxford report paints a bleak picture of the fake news situation. For example, since 2017, organized social media manipulation of false information has more than doubled.

Fake News in Politics

The interference in the 2016 US election is now a matter of record (recently reinforced by the testimony of foreign affairs expert Fiona Hill). But there’s another political case that demonstrates the pervasiveness of fake news. A dGen report on Brexit (the UK’s planned exit from the European Union) found that:

Fake news around the Brexit referendum was heavily influenced by bots. One study of ten million tweets, showed 13,493 bots appeared just before the referendum and then disappeared just after, suggesting the goal was to influence the vote.

The public were unable to get balanced information, and many failed to evaluate and cross-check the news they were getting.

Some journalists reported opinion instead of being objective in a bid to satisfy their audience.

There was bias in reporting on the EU; a later investigation found that 45% of BBC coverage was negative, compared to only 7% of stories that were positive.

Both social media and news coverage were biased toward the Leave position, and half of the activity of Leave-supporting Twitter users amplified tweets that supported that position.

Fake News and the Coronavirus

So, what are some of the rumors about the coronavirus that have now been debunked? Here are a few of the most persistent ones:

Anti-inflammatories like ibuprofen will increase the spread of Covid-19. This is false. However, because ibuprofen has side effects for people with certain conditions, many doctors now recommend paracetamol for treating coronavirus symptoms.

The “miracle mineral supplement” (MMS) mentioned earlier has been promoted as a coronavirus cure, but may actually cause vomiting and diarrhea because it contains chlorine dioxide.

Colloidal silver, other minerals, and certain types of teas, are being suggested as possible cures, though again, health authorities have said these are false.

There are multiple rumors about city shutdowns and quarantines. Most are false. Local authorities are the best source of reliable information on these.

Inhaling hot air from a hairdryer won’t help people with the coronavirus

Living in a hot climate, or exposure to cold, won’t stop the spread of the virus

Corona beer sales are down because of the similarity in the name. According to the company, US sales have actually increased.

The UK Government on Fake News

The issue has become so pressing that the UK government published a report into fake news. It concluded that:

The fake news epidemic was putting democracy at risk.

The laws that had been previously created for the newspaper age weren’t fit for the internet age.

The Psychology of Fake News

Another factor in the spread of fake news is human psychology. When our brains are overloaded, we have less time to make informed judgments. That can lead us to fall back on social proof.

In other words, if enough other people think that a particular story is true, we may well believe the same rather than go through the trouble of fact-checking it for ourselves. In fact, 59% of people share social media messages and stories without even reading them. Since we rely on cues to decide what we should trust, someone with an agenda who knows how to craft a story the right way and spread it via social media bots can easily manipulate our reaction.

In relation to fake news about the coronavirus, this plays into another aspect of human psychology says Stanford University professor Jeff Hancock. The global pandemic makes us uncertain, and we look for information to reduce that uncertainty. Information that makes us feel better or gives us a target to blame can help us to feel better. He says it’s one of the reasons for the extreme popularity of conspiracy theories.

Fake News and Digital Marketing

Since social media is one of the main ways fake news spreads, it’s helpful to see how it affects other areas of digital marketing. While email marketing is not a key tactic for spreading fake news, some marketers try to use fake news to their advantage via content marketing.

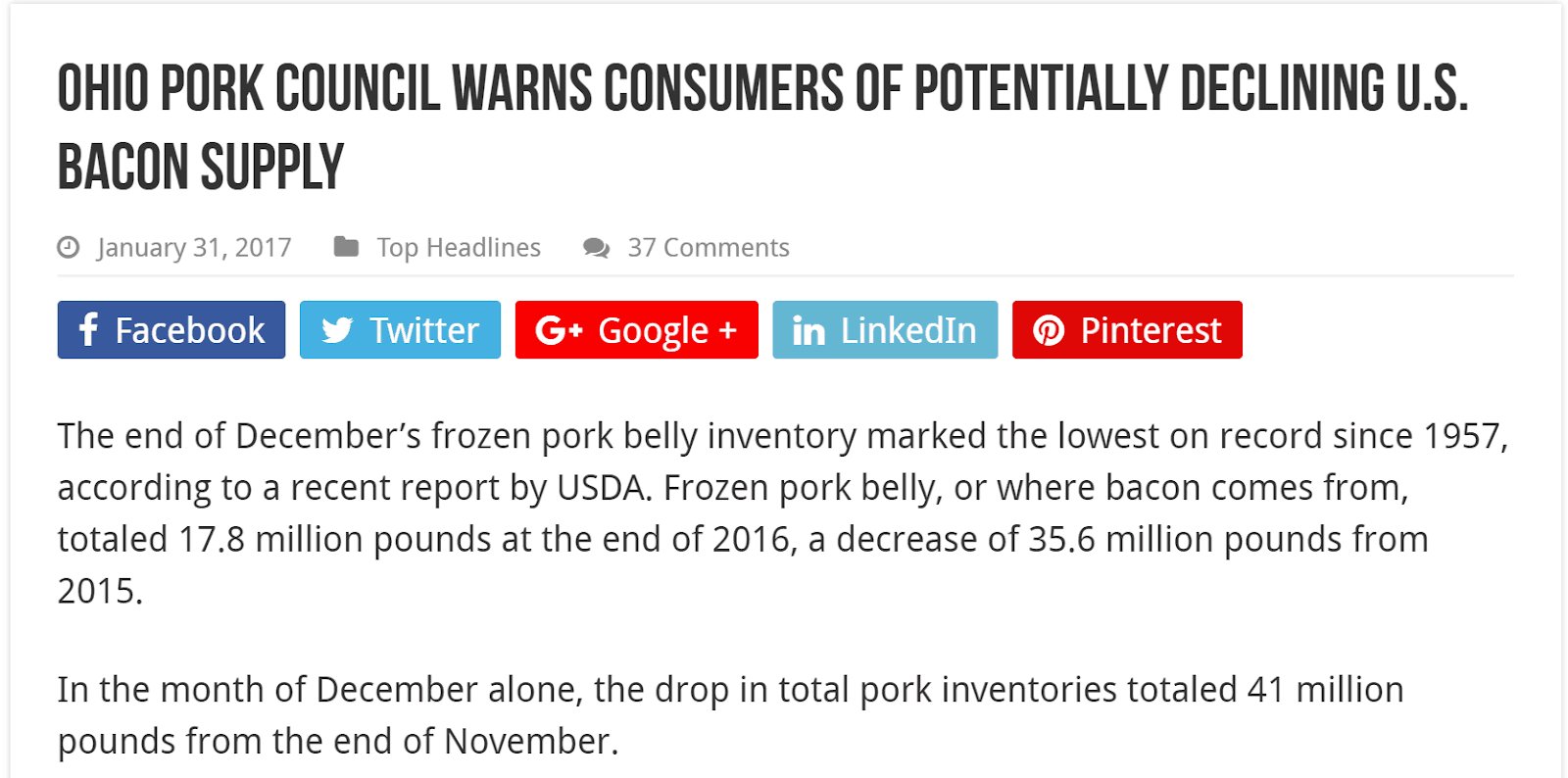

For example, the Ohio Pork Council created and promoted a story about a bacon shortage as a marketing ploy, and even set up a website to support the claims (it’s now offline).

The problem with using fake news as a marketing tactic is that it can backfire. In the case of the Ohio Pork Council, it may have engineered a short-term boost in bacon sales, but it could also make people less likely to believe the Council the next time it posts. In other words, publishing fake news (and sharing it via email marketing) can erode trust in your brand.

Does Fake News Hurt Your Brand?

As you can imagine, it’s not just a question of the erosion of trust when talking about the effect of fake news on your brand. Using fake news in your digital marketing results in poor quality and is a pretty lazy approach, says Smart Insights.

But there’s also another good reason why it is something that you want to avoid. It turns out that if ads and promotions for your company are placed next to fake news stories, then your brand is tainted by association. People will be less likely to buy your products, visit your store, or say something positive about your brand.

The best advice for any marketer is, instead of using fake news in content marketing, consider taking the opportunity to become known for trustworthy content. That’s because fake news has a big impact on how people see your brand.

Fake News and Social Media: What the Public Thinks

While the previously cited UK government report focused largely on the use of Facebook in the wake of the Cambridge Analytica scandal, one of its key conclusions was that Facebook is not accountable enough for what is being perpetrated via its platform. In fact, external attempts to hold the social media site accountable have met with limited success.

But accountability is exactly what social media users want. Research from the Chartered Institute of Marketing says that 85% of people believe that social media sites should be responsible for removing fake news. In addition, 79% think that social media platforms should monitor fake news.

As fake news stories continue to surface, trust in social media content is beginning to decline. The Chartered Institute of Marketing survey showed that, compared with 2014, the number of people who said they trusted content on social media had almost halved. It now stands at 34%, which means two-thirds of people don’t trust social media content. And only 1% of those surveyed were confident that the content they see on social media is genuine.

Despite this growing distrust, it seems fake news content still gets shared. And there’s no incentive for those peddling fake news to stay honest. If they keep getting clicks and shares, they’ll keep churning out fake news.

What Social Media Sites Are Doing About Fake News

With the finger of blame pointed squarely at Facebook and Twitter, the pressure is on for those sites to do something about the fake news epidemic.

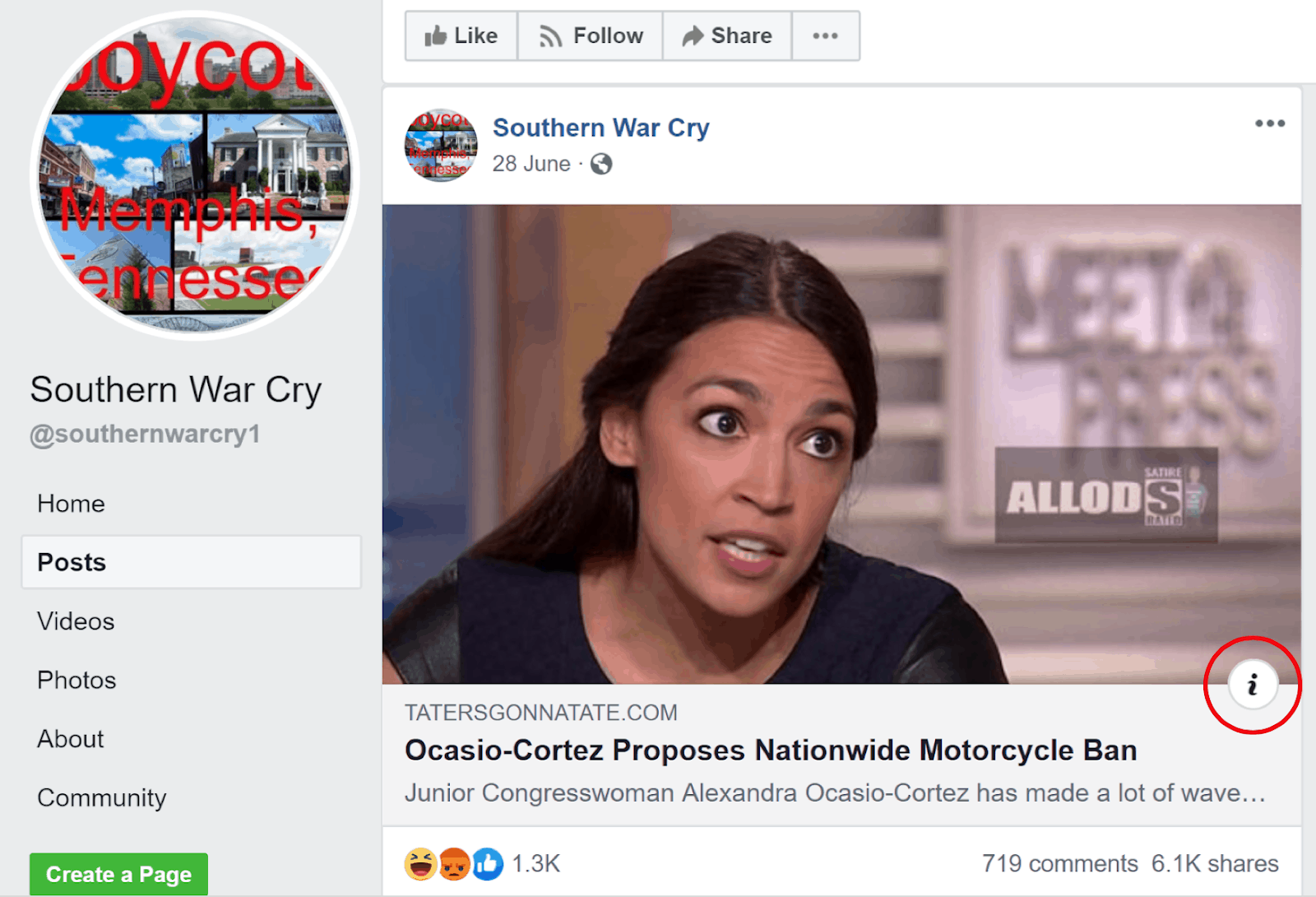

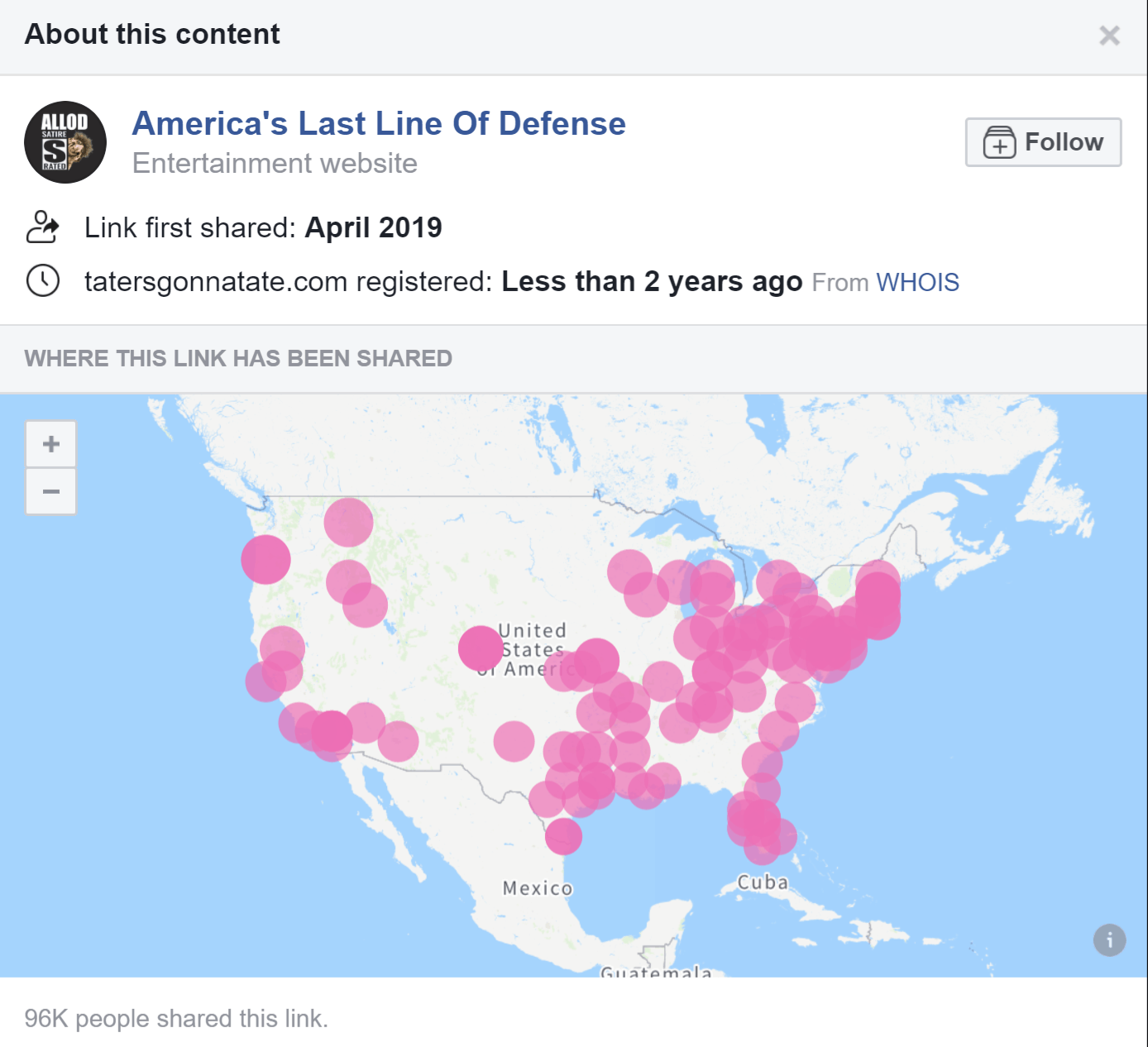

In the past year, there have been a number of initiatives. For example, Facebook has made it easier for people to check the source of a news story. Here’s how it works. News stories have a little information button you can click:

When you click, you get more information about the publication:

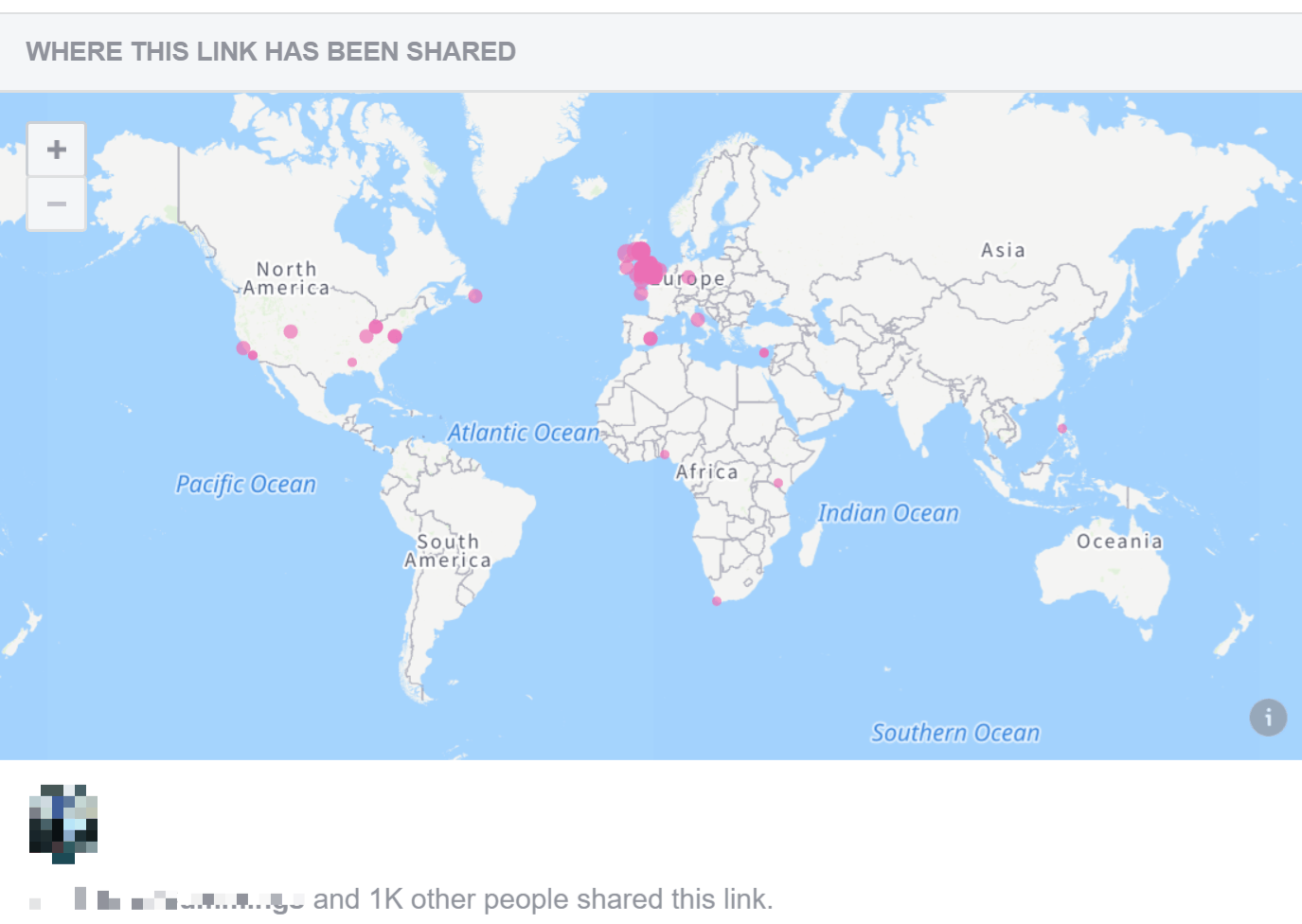

You can also see where it’s been shared, and how many people have shared it, including your friends:

Facebook has also said that, ahead of the 2020 US election, information will be fact-checked and clearly labeled to avoid the spread of fake news. Meanwhile, Twitter has announced that it will ban all political ads on the platform, something that Facebook has steadfastly refused to do. While it’s not a blanket ban on fake news, it should help address the issue, since so much fake news is about politics. And Instagram began a global rollout of improved fact-checking tools in December 2019.

How Tech Companies are Handling Coronavirus Fake News

The world’s biggest social media companies may usually be deadline rivals, but they’ve come together to combat the coronavirus fake news epidemic. Facebook, Google, Microsoft, Twitter, Linkedin, Reddit, and YouTube issued a joint statement to say they are working to:

Fight misinformation and fraud related to Covid-19 information

Give authoritative content on the virus a more prominent position on their platforms

Coordinate the sharing of valid information with government and care agencies worldwide

Actions include:

Banning misleading advertising (Facebook)

Banning content aimed at fostering panic (Facebook)

Verifying accounts that give access to official UK NHS advice (Twitter and Facebook)

Top Fake News Websites

Who’s originating the fake news that is being shared? It turns out that fake news is a big business, with many getting paid to come up with stories pushing a perspective, and start them off on their social media journey. For example, a Guardian report suggests a public relations firm received a payment of $2,000 for promoting biased newspaper articles in support of one candidate running for Congress.

A story in The Hindu suggests that Indian interests are managing 265 fake news sites in more than 65 countries. And CBS published a list of common fake news sites, including:

Infowars

Your News Wire

World News Report

TheBostonTribune.com

ChristianTimes.com

NationalReport.net

There are dozens more, many collated in this list on Wikipedia.

How to Combat Fake News

It’s a worrying trend that some people are unable to distinguish between real news and fake news. Here are some ways that you can avoid being among them.

NPR suggests that it pays to be skeptical about what you view online. Just as you do when you’re preparing a research paper, look to see if the same information is coming from different sources.

Importantly, these have to be sources that are known to be trustworthy, such as reliable news sources or unbiased government or educational websites. It’s even more important to do this due diligence on hot button topics or issues where some people could benefit from pushing a particular viewpoint or agenda. Check that the statements presented in an article are verifiable by looking for the sources.

Since we can’t always trust that publications or organizations will verify the information for us, it is important to take matters into our own hands. Luckily, while apps and algorithms can help spread fake news, they can also help you to identify it and stop it in its tracks. It’s just a matter of training the algorithms to recognize it.

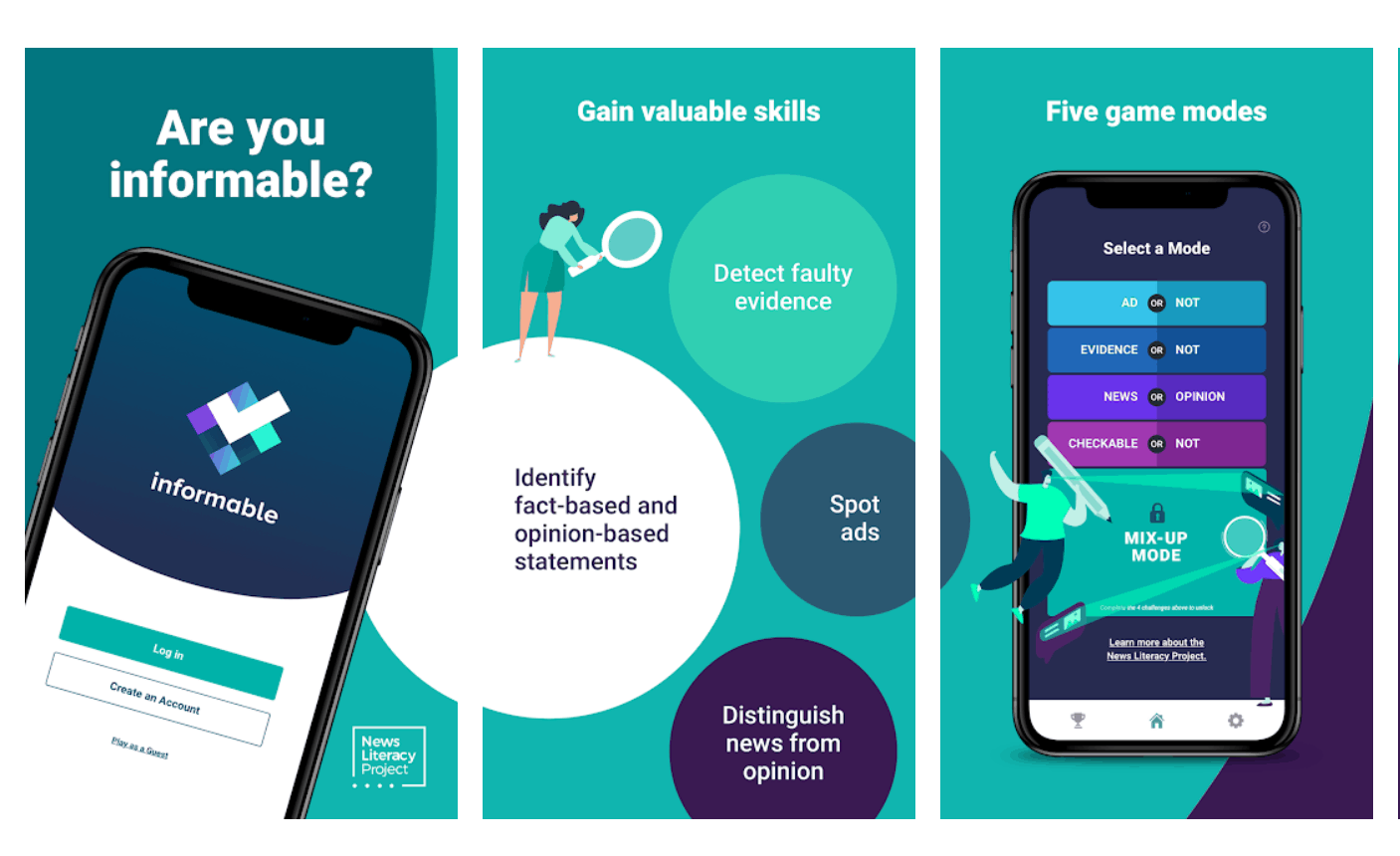

One option for fact-checking is the Informable app from the News Literacy Project.

The app helps you figure out whether:

Stories are news or opinion

Stories are really ads

Claims in the stories are backed up

WhatsApp, another common source for spreading unverified information, has its own checklist of things to look out for. One key tip is to be aware that, even if something is shared multiple times, it doesn’t necessarily make it true.

The social messaging app urges you to:

Pay attention to messages that have been forwarded so that you can tell whether they originated from the person that sent them to you

Check whether photos have been doctored

Look out for suspicious links

Help stop the spread of fake news by asking the person who sent information to you to verify it before you share it yourself

An app called Check by Meedan helps you fact check WhatsApp stories.

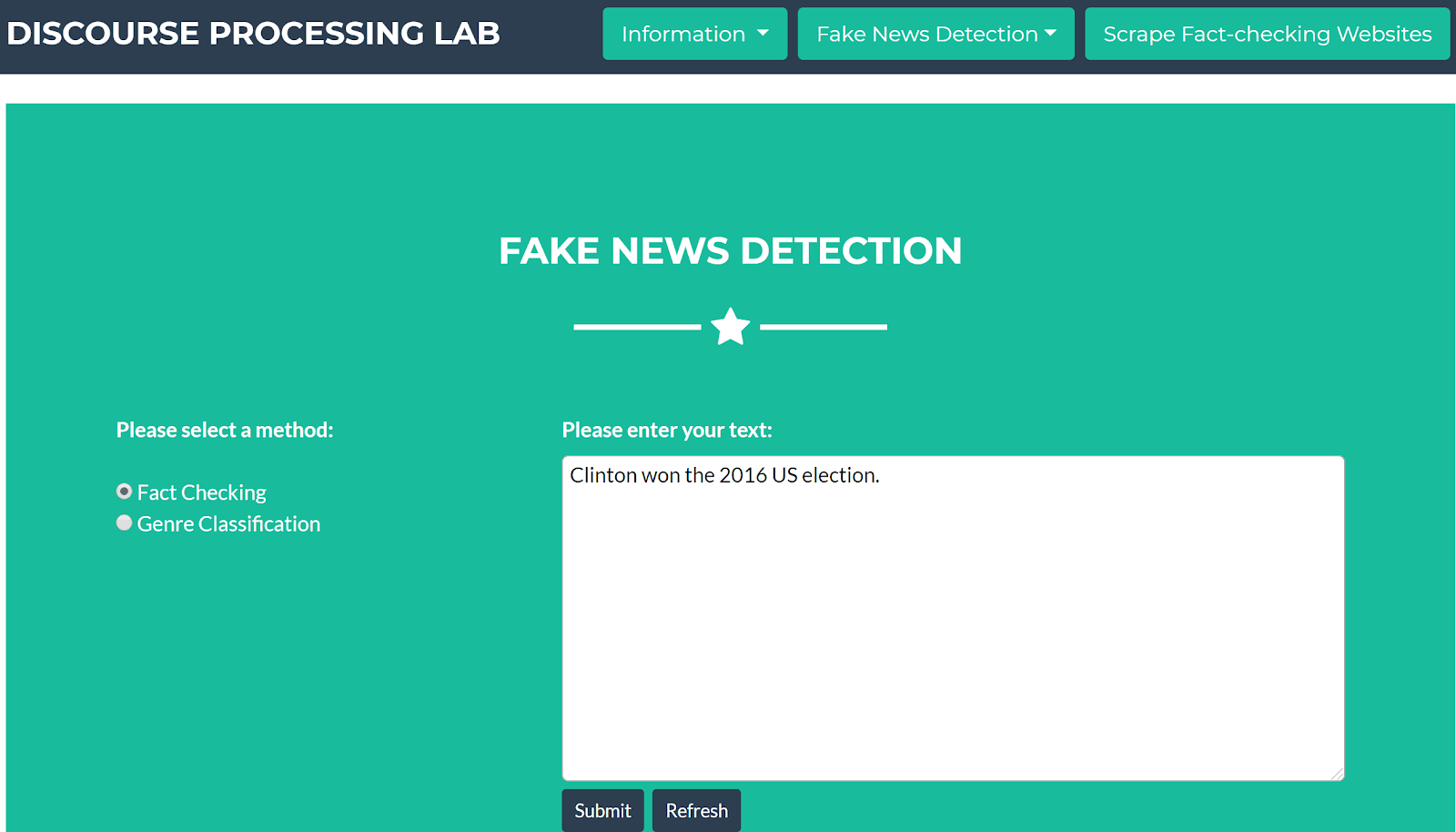

And there’s an experimental fake news detector where you can type in a story and immediately check its veracity.

That’s because research suggests that there are subtle differences in language between verified information and a fake news story.

Meanwhile, Wikipedia founder Jimmy Wales has launched WT Social, a paid news-focused social media site that aims to share only verified information.

The UK government has simplified spotting fake news into a five-point checklist, which it calls the SHARE checklist:

Source – check if the source is trustworthy

Headline – ask yourself if what follows the headline is believable

Analyze – check the facts

Retouched – see if the image has been manipulated

Error – watch out for fake URLs, especially those that have been badly spelled

Finally, you can also check fake news on Snopes.com and other popular myth-busting sites.

Where to Find Reliable News About the Coronavirus

If you’re looking for reliable information about the coronavirus, here are some useful resources:

The World Health Organization’s coronavirus updates page

The Centers for Disease Control in the US

The NHS in the UK

Reputable news sources either within your country, or those that offer global live coverage like the BBC and CNN

Your country’s, city’s or town’s official health information

Global statistics on Covid-19 cases, like this page from Worldometer

Next, we look at what you do if you find fake news on a particular platform.

How to Report Fake News

As social media and web users, we all have a part to play in combating the spread of fake news. Don’t just recognize and ignore fake news; help to stop it by reporting it. Every fake news story we successfully get rid of makes the web a slightly more trustworthy place.

Most social media sites have an easy way for you to report spam. Recently, many have expanded this functionality to allow social media users to report misleading information.

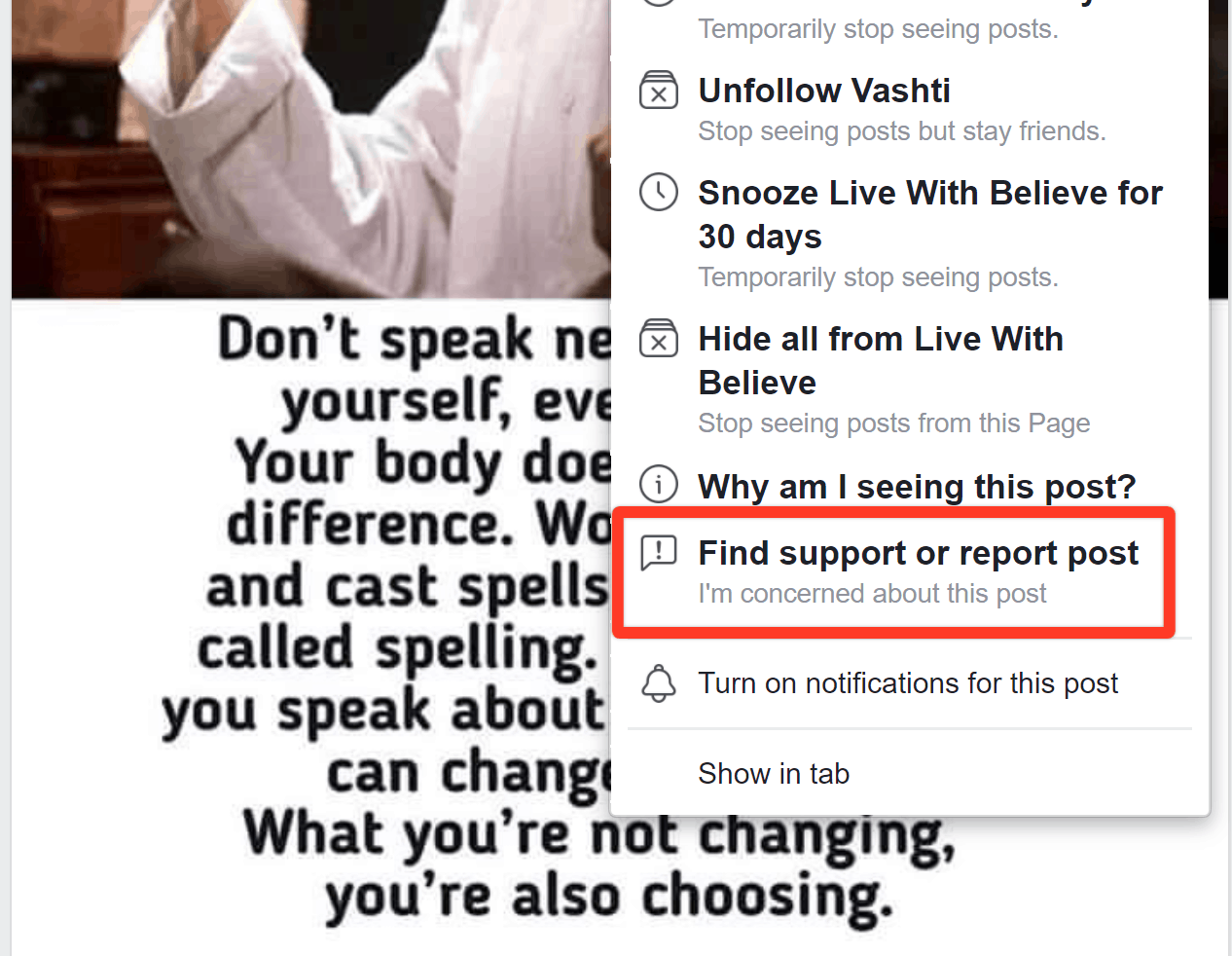

Facebook has functionality to let you report misleading accounts. For example, if you suspect your friend’s account has been cloned or hacked, you can report any information you believe to be false. This functionality works for flagging questionable material, too.

Once you click on Find support or report posts, you can report fake news directly. There are several options for feedback on questionable content, including marking it as false news.

Similarly, Twitter allows you to easily flag and report spam accounts. And in 2019 it launched a tool to help people report fake news directly during election campaigns. This adds “it’s misleading about voting” to the other reporting options.

You can also report false information on Instagram. And in Google search results, you can use the feedback tool to report misleading information and attach a screenshot of it.

The Future of Fake News

Is fake news here to stay? It seems like it. People are more informed about fake news than they were in the past, but that still doesn’t mean that they are able to spot it.

A report looking at fake news in the US in 2018 found that people saw less fake news that year than they had the year before. However, some people, such as hardcore partisans on both sides of a political battle, see quite a lot of it.

Plus, if you’re on platforms like Twitter, where US President Donald Trump posts regularly, you’re even more likely to be subjected to fake news. Since taking office, he’s known to have made more than 15,000 misleading statements. And he’s also been shown to have made several false claims about the spread of coronavirus and responses to the pandemic in the US.

Although social media sites are taking steps to safeguard users against fake news, these measures seem woefully inadequate. A test by Nieman Lab showed that Facebook itself was only able to spot 30% of fake news stories. That suggests that 70% of fake news stories could still be seen and shared.

Options for muting and blocking certain content are also inadequate. In an ideal world, social media sites would be so good at weeding out fake news that users would never see it at all. That doesn’t look like it’s going to happen any time soon.

In fact, fake news remains a huge cybersecurity issue and a threat to democracy.

There is some hope. As Mark Schaefer points out, one of the big issues surrounding fake news is the lack of laws surrounding its publication. But one country has already started to deal with that issue.

Singapore’s controversial Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulations Act (POFMA) came into effect in October 2019. Under the law, those found to be publishing false information that goes against the interests of the country could attract fines of up to $720,000 (USD) and jail terms of up to ten years. For this reason, it’s been criticized as a law that allows for the stifling of dissent.

Within a month, that law had been applied for the first time to a Facebook post questioning whether investment firms were independent. As a result, a correction notice and a link to a government statement about the post were added to the original post.

Other countries taking steps to fight fake news legally include France, Germany, China, and Kenya. In some cases, it’s because of upcoming elections; while in others, it seems like a case of being prepared.

What Next for Fake News?

In the 21st century, we’re in the reputation era where being trustworthy is more important than ever before. This is especially important among younger millennials, who are already interested in companies’ ethics, are a major consumer segment, and who will soon be of voting age. And it’s essential when the spread of fake news affects our ability to get reliable information about the coronavirus pandemic.

Self-regulation isn’t yet effective, so legal remedies such as the Singapore law may become the only option for fighting fake news. Another valid approach is education. Finland has tried this with some success, and is now ranked as the most media literate country in the world.

Meanwhile, the European Union has an action plan to address online disinformation and the Law Library of Congress is collecting information on initiatives around the world to combat fake news. There’s also a sliver of hope from online activist group Avaaz, which actively fights online misinformation, and reports on fake news.

These may provide more strategies for fighting fake news in the long run. One thing’s for sure, though, with elections happening constantly around the world, and people invested in influencing voter opinion, the issue of fake news isn’t going away any time soon.

To Recap

In this in-depth guide, you’ve learned:

How fake news is defined, and some of the other key terms that describe this kind of online falsehood

Different types of fake news, ranging from those intended as satire to those intended to deliberately deceive

The rise of fake news including a peak period around the 2016 US election and Brexit

How technology is used to create and spread fake news with some help from human sharers

The impact of fake news in digital marketing

How you can spot and report fake news and what social media sites are doing about it

What’s likely to happen with fake news in the near future

Sharon Hurley Hall

Sharon Hurley Hall is a professional writer and blogger. Her work has been published on Jilt, OptinMonster, CrazyEgg, GrowthLab, Unbounce, OnePageCRM, Search Engine People, and Mirasee. Sharon is certified in content marketing and email marketing. In her previous life, Sharon was also a journalist and university journalism lecturer.

No comments:

Post a Comment