Again it is curious that i never quite knew the early history, but only later about Boole, Yet i have see the images before and also knew not.

Even today, contemplating the ancient symbol of the I Ching means zero unless you understand it in three dimensions. I just told you that and i am sure you will just screw it up.

All this is important and it is repeated over and over again. ultimately it all addresses the question of what GOD is. And you are still lost in the wilderness of knowledge.

The Perpetual Quest for a Truth Machine

Why human attempts to mechanize logic keep breaking down.

BY KELLY CLANCY

July 8, 2024

https://nautil.us/the-perpetual-quest-for-a-truth-machine-702659/

In the 13th century, the young married patrician Ramon Llull was living a licentious life in Majorca, lusting after women and squandering his time writing “worthless songs and poems.” His loose behavior, however, gave way to a series of divine revelations. His visions urged him to write what he believed would be the best book conceived by a mortal: a book that could converse with its readers and truthfully answer any question about faith.

It would be, in a sense, an early chatbot: a mechanical missionary that could be sent to the farthest reaches of humanity to convert any unbeliever with undeniable truths about the universe. Europeans had spent the past two centuries attempting to win hearts through the blood-drenched Crusades. Llull was determined to invent a linguistic device that would communicate a higher truth not through violence, but fact.

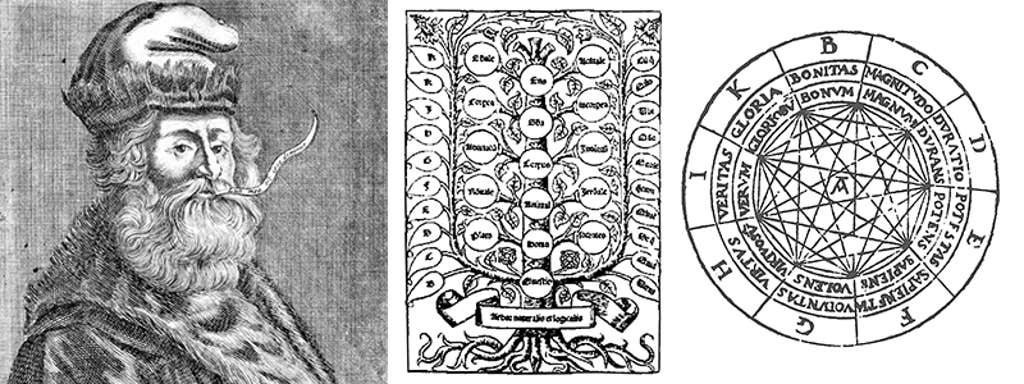

His main works, collectively known as Ars Magna, described a sort of logic machine: one that, Llull claimed, could prove the existence of the Christian God to even the most stubborn heretic. Llull likely took inspiration from the zairja, another combinatorial device, which Muslim astrologers used to help generate new ideas. In the zairja, letters were distributed around a paper wheel like the hours on a clock. They could be recombined to answer questions through a series of mechanical operations.

Llull divided his machine’s paper wheels into fundamental religious concepts, including goodness, eternity, understanding, and love. Users would rotate a series of concentric paper discs mounted on threads to combine different divine attributes into logically true statements. It was hardly a turnkey system—potential converts would have to study for months to be able to consult it. And Llull’s obsessively detailed examples obfuscated, rather than revealed, how the machine worked. But his hope to derive truth through the reduction—and mechanical recombination—of knowledge into basic principles and terms prefigured contemporary computing by nearly 800 years.

Although Llull was certain his logic machine would demonstrate the truth of the Bible and gain new Christian converts, he was ultimately unsuccessful. One report has it that he was stoned to death while on a missionary trip to Tunisia.

Humans exist at an uneasy threshold. We have a dizzying ability to make meaning from the world, braid language into stories to construct understanding, and search for patterns that might reveal larger, more steady truth. Yet we also recognize our mental efforts are often flawed, arbitrary, incomplete.

Woven throughout the centuries is a burning obsession with accessing truth beyond human fallibility—a utopian dream of automated certainty. Llull, and many thinkers since, hoped a sort of machine could operationalize logic through language to end disagreements—and perhaps even war—opening access to a single, indisputable truth. This has been the seduction of modern computers and artificial intelligence. If our limited human minds can’t alight—or agree—on pure, rational truth, perhaps we could invent an external one that can, one that would use language to calculate our way there.

COMPUTING TRUTH: Thirteenth-century philosopher and theologian Ramon Llull conceived of a technology that would provide unerring truth about the universe. He most likely took inspiration from a spinning device used by Muslim astrologers before him. Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

For at least a millennium, humans have attempted to take these two marvelously malleable and uniquely human abilities—abstract thinking and descriptive language—and outsource them to something more rational.

In the 17th century, mathematician Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz created a mechanical—but descriptive—logic machine. In Dissertatio de Arte Combinatoria, published in 1666 when he was 19, Leibniz proposed that all concepts could be described as combinations of simpler concepts, in the same way words are composed of letters.

Leibniz admired Llull’s Ars but found it lacking. Its basic concepts were too arbitrary: Why goodness, eternity, and love, for instance, and not others? To mechanically simulate logic, Leibniz suggested, we needed to discover the full alphabet of human thought: the basic set of concepts from which all others could be constructed. It would be a divine language that, as he wrote in a later letter, “perfectly represents the relationships between our thoughts.”

Woven through the centuries is a utopian dream of automated certainty.

Leibniz hoped this would lead to the language in which God wrote the universe, one in which no untruth could be spoken. Leibniz believed his own “mother of all inventions” would usher in utopia, accelerate science, and perfect theology. He hoped to create a machine that could provide certainty in any realm, be it philosophy or politics, medicine or physics. Lines of reasoning in any field would become as “tangible as those of the Mathematicians,” he wrote. Instead of disagreeing, people would feed their questions into this logic machine, declaring: “Let us calculate, without further ado, to see who is right.”

Like René Descartes before him, Leibniz believed truth could be discovered through reason alone. Jonathan Swift, for one, ridiculed the notion. In his 18th-century satiric novel Gulliver’s Travels, Swift portrayed scholars at the Grand Academy of Lagado using an “engine” to write books. A spoof of Leibniz’s machine, the Lilliputian engine consisted of a wire mesh string on which hung dice inscribed with words. Scholars would hand crank the wires to spin the dice and create new combinations of words. Philosophers would then record these combinations into books “without the least assistance from genius or study.”

Undeterred by such public scoffing, scholars continued to try to build a truth-generating machine. English mathematician George Boole had a visionary insight at the age of 17 into the nature of the mind and how it “accumulates knowledge.” Decoding this vision became his life’s work. Like Llull and Leibniz, he grew obsessed with the idea of creating a system of language that could put disagreements to rest and calculate truth by mathematical certainty. This led Boole to his 1854 book, Laws of Thought, in which he pioneered a novel form of logic predicated on a new measure of truth: yes or no.

No comments:

Post a Comment