As if anyone understood time let alone TIME. More interesting is my conjecture that nothing passes through the event horizon except to top up the supply. After all the surface is not smooth at all and certainly not mathematically smooth. The rest is torn apart and converted back to photonic form and is then carried off away from the event.

Just how do plasma jets get created? If material would never look like they do. They are a bolt of photonic energy carrying off information and then along the way often decaying back into the particle form and then decaying to produce light we can observe. All far from the gravity well wghich caused it all.

We may still have non radiating Black holes simply because they are not been fed and may have been formed alternately to star collapse in the void. Star collapse must deal with the material content and what i just described solves that problem.

How Black Holes Nearly Ruined Time

Quantum mechanics rescued our understanding of past and future from the black hole.

BY ANDREW TURNER & ALEX TINGUELY

January 23, 2019

https://nautil.us/how-black-holes-nearly-ruined-time-rp-8107/

This essay is one of the five winners in the 2019 writing competition held by the Black Hole Initiative at Harvard University. “The Black Hole Initiative offers a unique environment for thinking about the topic of black holes more creatively and comprehensively,” says BHI director, Avi Loeb. To add context to the exciting April 10 announcement that astronomers have observed a black hole for the first time, this week Nautilus is featuring all five winning essays.

Black holes are mystifying objects that have captivated our imaginations since their existence was first proposed. The most striking feature of a black hole is its event horizon—a boundary from within which nothing can escape. Objects can cross the event horizon from outside to inside, but once they do, they can never cross back, nor can any information about them; anything that crosses the event horizon of a black hole is cut off entirely from the outside universe.

For many years, the existence of black holes seemed to threaten a fundamental tenet of modern physics called the second law of thermodynamics. This law helps us to distinguish the past from the future, thus defining an “arrow of time.” To understand why black holes posed this threat, we need to discuss time reversal and entropy.

Entropy and the Arrow of Time

Based on our observations, the laws of physics are (mostly) invariant under time reversal. What does this mean? Imagine a friend shows you the following video: A pendulum swings across the screen from left to right. Is this video being played normally or in reverse? Well, you have certainly seen a pendulum swing the other way before. If the laws of physics do not change under time reversal, then there is actually no way to tell: Physics looks the same with time playing forward or backward.

However, this doesn’t seem to jibe with our daily experience. Consider another video in which a bunch of ceramic shards fly up off the floor and assemble themselves into a coffee mug before coming to rest on a table. Is this video being played forward or backward? Most people would reasonably guess that the video was being played in reverse. If the laws of physics are truly invariant under time reversal, why does this intuition seem so obvious to us? The reason is that, although the laws of physics technically allow for this bizarre process to occur as shown in the video, the fact that the broken mug is made up of many, many particles means that it is essentially impossible for it to spontaneously reassemble itself.

This concept is formalized by the second law of thermodynamics, which tells us that a certain quantity, the entropy S, of any isolated system cannot decrease over time (but can increase). In other words, the change in entropy cannot be negative:

∆S ≥ 0 .

The entropy S is a statistically defined notion measuring our lack of knowledge about the underlying state of a system when we only know “macroscopic” (large-scale) information about it. By “state” here, we mean the exact configuration of each particle making up the entire system. For example, consider a box filled with gas. While we can easily measure the temperature and pressure of the gas, it is practically impossible for us to know the position and velocity of each gas particle within the box. In fact, there are many configurations of particle positions and velocities, i.e. states, that would give rise to the same temperature and pressure. The entropy encodes our ignorance of which specific state the system is actually in.

The greater the number of states that are consistent with the same temperature and pressure, the greater the entropy.

The fact that the entropy cannot decrease over time—but can increase—follows from invariance under time reversal combined with an additional property called causality. Together, these tell us that any single state of a system corresponds to exactly one state at any point in the past or in the future—no more, and no fewer. For example, one state cannot become two states at some point in the future, and two states cannot become one state.

\

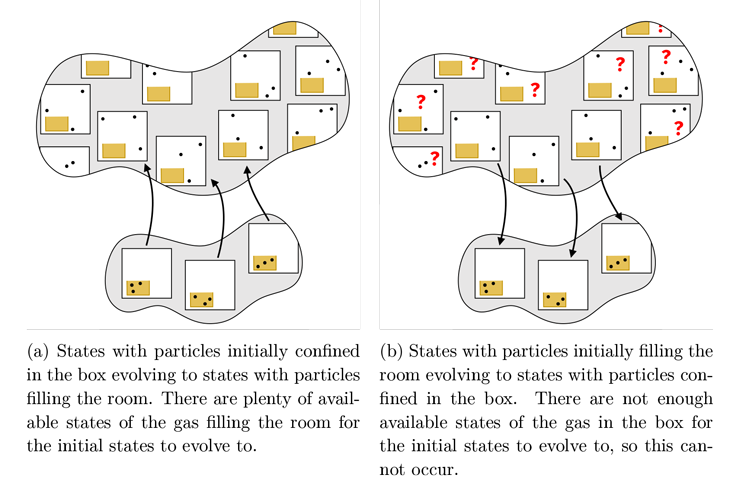

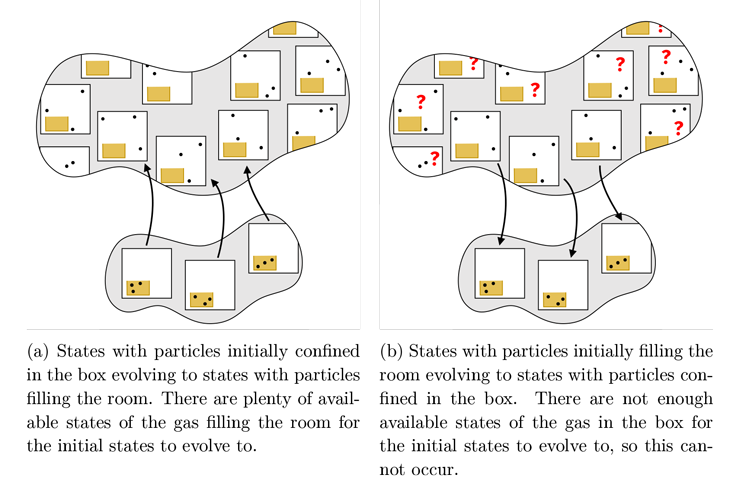

Figure 1: The sets of possible states of the gas when confined to the box (lower set) and when filling the room (upper set). Each square shows one possible state of the gas particles. The upper set is much larger because there are many more possible states in which the gas fills the room.

Now consider what happens when we open our box of gas into a large room. If the gas starts in the box and then flows out to fill the room, as in Figure 1a, then we can easily satisfy the rule that each initial state in the box evolves to a unique final state in the room. If we were paying close attention to every particle in the room during this process, the entropy couldn’t increase because each initial state evolves to a single final state, but we can’t keep track of so many variables; all we are able to do is measure the temperature and pressure after opening the box, and we will find that there are many, many more possible states of the gas in the whole room that are consistent with the new temperature and pressure. During this process, we lose information about the exact configuration of the particles, and thus the entropy increases. If instead the gas starts in the room and then flows into the box, as in Figure 1b, then the vast majority of the initial states in the room have nowhere to go—there simply aren’t enough states in the box. Thus, the entropy cannot decrease!

The second law of thermodynamics now gives us some sense of an “arrow of time.” Despite the fact that the laws of physics are time-reversible, the statistical notion of entropy allows us to define a forward direction for time: Time flows forward in the direction that entropy increases! This is why we feel that a video of a spontaneously reassembling coffee mug must be playing in reverse.

Black Holes and Entropy

Now, what does this all have to do with black holes? Classical black holes—the kind that would exist in a world without quantum physics—have no entropy. Physicist Jacob Bekenstein once said that these classical black holes “have no hair,” a cute phrase meaning that a classical black hole only has a few measurable properties: mass (how big it is), angular momentum (how fast it is spinning), and electric charge (like built up static electricity). When an object falls into a black hole, it contributes to these three quantities, but other than that, any information about it is lost forever.

This is a big problem for the second law of thermodynamics! If black holes truly had no entropy, then any time an object fell into a black hole, its entropy would effectively be deleted, reducing the entropy of the universe and violating the second law of thermodynamics. Without the second law of thermodynamics, why shouldn’t we see coffee mugs reassembling themselves in our day-to-day lives?

The resolution to this problem is to add quantum physics into the mix. In 1974, the late Stephen Hawking showed that in addition to the three properties above, black holes also have a temperature, now known as the Hawking temperature. The thermodynamic definition of temperature relates changes in energy to changes in entropy, so this revelation allowed Hawking to show that black holes actually do have entropy, consistent with the second law of thermodynamics. In fact, because the energy of a black hole increases when the surface area of its event horizon increases, it turns out that the entropy of a black hole is proportional to its surface area, a fact originally conjectured by Bekenstein.

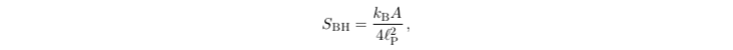

Hawking’s discovery of the exact value of the Hawking temperature allowed him to compute the constant of proportionality, resulting in what is now known as the Bekenstein–Hawking (conveniently, the same letters as “Black Hole”) formula:

where SBH is the black hole’s entropy, A is its surface area, and kB and 𝓁P are constants known as the Boltzmann constant and the Planck length, respectively. This formula was later verified in a particular theory of black holes by the calculations of physicists Andy Strominger and Cumrun Vafa, as well as others.

The punchline is that black holes do have entropy, exactly as we had hoped, and we can tell exactly how much they have just by looking at how big they are. Once we know that black holes have entropy, we have a new form of the second law of thermodynamics that includes not only the universe outside the black hole, but also the universe within the event horizon: The total entropy, Stotal = Soutside + SBH, must never decrease. Whenever something is thrown into the black hole, the entropy Soutside of the universe outside the black hole decreases, but amazingly the surface area of the black hole, and therefore SBH, increases enough to ensure that Stotal does not get smaller. Thus, the second law of thermodynamics and the arrow of time are saved!

Andrew Turner is a graduate student in the MIT Center for Theoretical Physics, conducting research on string theory and supergravity. Originally from Ashland, Missouri, he is a graduate of Harvey Mudd College.

Alex Tinguely is a graduate student in the MIT Department of Physics, conducting fusion energy research at the Plasma Science and Fusion Center. He is originally from Fort Madison, Iowa.

This essay placed fourth in the Black Hole Institute’s essay contest.

No comments:

Post a Comment