What this does do is eliminate the idea that a giant thunder bird is simply too large to have existed. They are certainly possible because these also existed.

Then we have the claim that they are extinct. I am not so sure, not least because we do have recent thunder bird sightings. Better yet it is plausible to suggest a global distribution of such birds anyway.

Oiur knowledge of eagles comes largely from bald headed eagles which rely on fishing. This makes them daytime hunters.

Anything like these giants will hunt at night and go to ground during the day. That means sitting inside the skirt of a large conifer giving 360 degree observation.

What is important is that we have fossil .confirmation. Actual specimans will be far harder.

Paleontologists ‘Discover’ Fossil of Giant Extinct Eagle That Dwarfed Modern Raptors, Could Kill Kangaroo

BY MICHAEL WING TIMEAPRIL 1, 2023

https://www.theepochtimes.com/paleontologists-discover-fossil-of-giant-extinct-eagle-that-dwarfed-modern-raptors-could-kill-kangaroo_5143646.html?

Fossil hunters Down Under have pieced together the story of a colossal prehistoric raptor—a bird so huge its talons could have killed a kangaroo.

The bones of a giant avian were collected from South Australia’s Mairs Cave by cavers back in 1956 and 1969. After long delays, new research conducted by scientists from Flinders University has ascertained the bird’s species, making the discovery finally “official.”

They named the raptor dynatoaetus gaffae, or Gaff’s powerful eagle.

The eagle is closely related to Old World vultures of Africa and Asia, such as the monkey-eating eagle, or Philippine eagle. Researchers say, with its mighty wingspan and powerful talons, the now-extinct eagle was a top avian predator of the late Pleistocene.

A wedge-tailed eagle, Australia’s largest bird of prey.

Researchers from Flinders University descend into a cave located in South Australia’s Flinders Range. (Courtesy of Aaron Camens)

Paleontology researcher Dr. Ellen Mather organized a field trip to South Australia’s Flinders Range in 2021, where four large bones had been extracted by the cavers decades earlier.

“After half a century, and several delays caused by the pandemic, the expedition with volunteers from the university’s Speleological Society found a further 28 bones scattered about deep among the boulders at the site indicated by one of these museum relics,” Mathers stated in a press release.

They made the discovery by repeating measurements taken 60 years earlier when the cavers first descended into a rock pile and discovered the large fossil of an eagle in crevices.

A size comparison of today’s wedge-tailed eagle and the now-extinct dynatoaetus, based on fossil sizes. (Courtesy of Ellen Mather)

A size comparison of today’s wedge-tailed eagle and the now-extinct dynatoaetus, based on fossil sizes. (Courtesy of Ellen Mather)With the fresh find, the researchers pieced together a clearer picture of the bird’s anatomy.

The newly unearthed fossils were matched with historic remains from collections at the South Australian Museum and the Australian Museum, helping complete the puzzle.

These additional museum pieces were originally sourced from locations spanning Lake Eyre Basin in Central Australia to the Wellington Cave complex in New South Wales.

Thanks to the researchers’ “serendipitous osteological sleuthing,” they confirmed the size and other details about the gigantic bird.

“It was humongous—larger than any other eagle from other continents, and almost as large as the world’s largest eagles once found on the islands of New Zealand and Cuba, including the whopping, extinct 13-kilogram Haast’s eagle of New Zealand,” said Associate Professor Trevor Worthy from New Zealand, who partook in the extraction.

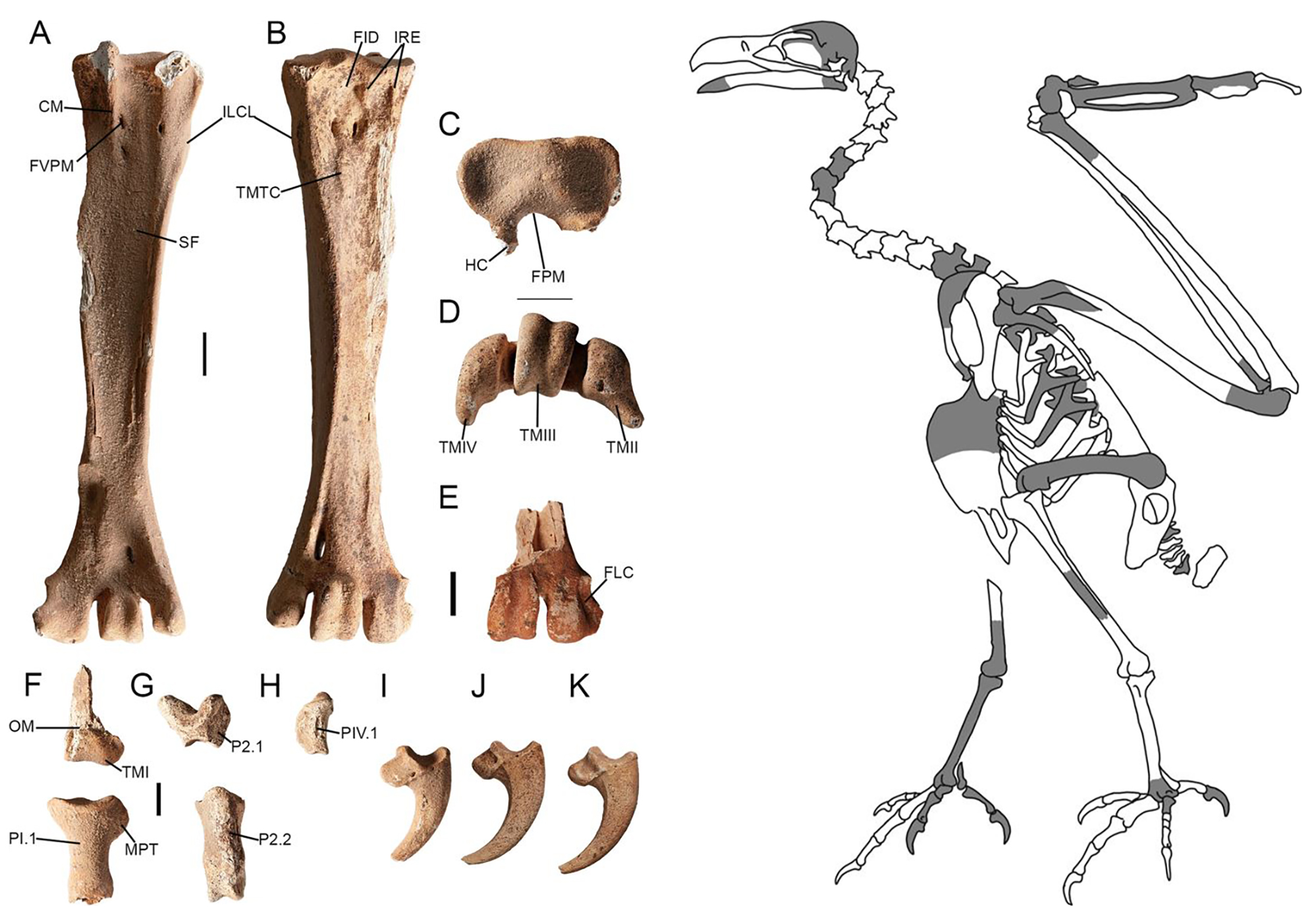

(Left) Several of the fossils used in the research with notation: (A), dorsal (B), proximal (C) and distal (D) aspect, fragment of right distal tarsometatarsus from Victoria Fossil Cave (SAMA P.28008) in dorsal (E) aspect, along with the os metatarsale and first phalanx of pedal digit I (F), first and second phalanges of digit II (G), first phalanx of digit IV (H), and three ungual phalanges (SAMA P.59525, I; SAMA P.19157, J; SAMA P.17139, K) from Mairs Cave. CM crista medianoplantaris, FID fossa infracotylaris dorsalis, FLC fovea ligamentum collateralis, FPM fossa parahypotarsalis medialis, FVPM foramen vasculare proximale medialis, HC hypotarsal crista, ILCL impressio ligamentum collateralis lateralis, IRE impressiones retinaculi extensorii attachment scars, MPT medial plantar tuberculum, OM os metatarsale, PI.1 phalanx 1 digit 1, P2.1 phalanx 1 digit 2, P2.2 phalanx 2 digit 2, PIV.1 phalanx 1, digit 4, SF sulcus flexorius, TMII trochlea metatarsi II, TMIII trochlea metatarsi III, TMIV trochlea metatarsi IV, TMTC tuberositas m. tibialis cranialis. Scale bars are 10 mm. (Right) A visual representation of the parts of the skeleton from dynatoaetus (colored grey).

Researchers from Flinders University collect fossils from a cave located in South Australia’s Flinders Range. (Courtesy of Aaron Camens)

Researchers extract fossils of now-extinct dynatoaetus inside a cave located in South Australia’s Flinders Range. (Courtesy of Aaron Camens)

Worthy has excavated several Haast’s eagle skeletons during his more than 30 years of research.

Dynatoaetus possessed giant talons, as long as 12 inches (30 centimeters), Worthy added, with which it “easily would have been able to dispatch a juvenile giant kangaroo, large flightless bird, or other species of lost megafauna from that era, including the young of the world’s largest marsupial, diprotodon, and the giant goanna, varanus priscus.”

The raptor would have coexisted alongside still-living raptor species, such as the wedge-tailed eagle. This fact carries interesting implications.

“Given that the Australian birds of prey used to be more diverse, it could mean that the wedge-tailed eagle in the past was more limited in where it lived and what it ate,” Mather said. “Otherwise, it would have been directly competing against the giant dynatoaetus for those resources.”

A wedge-tailed eagle. (TORSTEN BLACKWOOD/AFP via Getty Images)

Dr. Ellen Mather holds up bones from two different species for size comparison, with a modern-day wedge-tailed eagle’s bone on the left and a dynatoaetus fossil on the right. (Courtesy of Tania Bawden)

Along with the recently described cryptogyps, an enormous vulture-like raptor, dynatoaetus is also unique to Australia. Both went extinct around 50,000 years ago.

“We were very excited to find many more bones from much of the skeleton to create a better picture and description of these magnificent long-lost giant extinct birds,” Mather said.

“It’s often been noted how few large land predators Australia had back then, so dynatoaetus helps fill that gap.”

The newly found eagle was named in honor of Victorian paleontologist Priscilla Gaff, who first described some of the fossils in her 2002 master of science thesis.

No comments:

Post a Comment