He is well worth remembering for his clear thinking on the subject.

what i bring into this discussion is that mathematical infinity itself does not exist in our physical universe, even if we can imagine it. This means time is also finite and what we see out there are time modified photons. thus the rad shift as we look back in time.

also understand that a Galaxy is sublight so it is obviously finite. That is why we see what we see.

Is it possible to produce sublight Voids to produce content without consiousness?

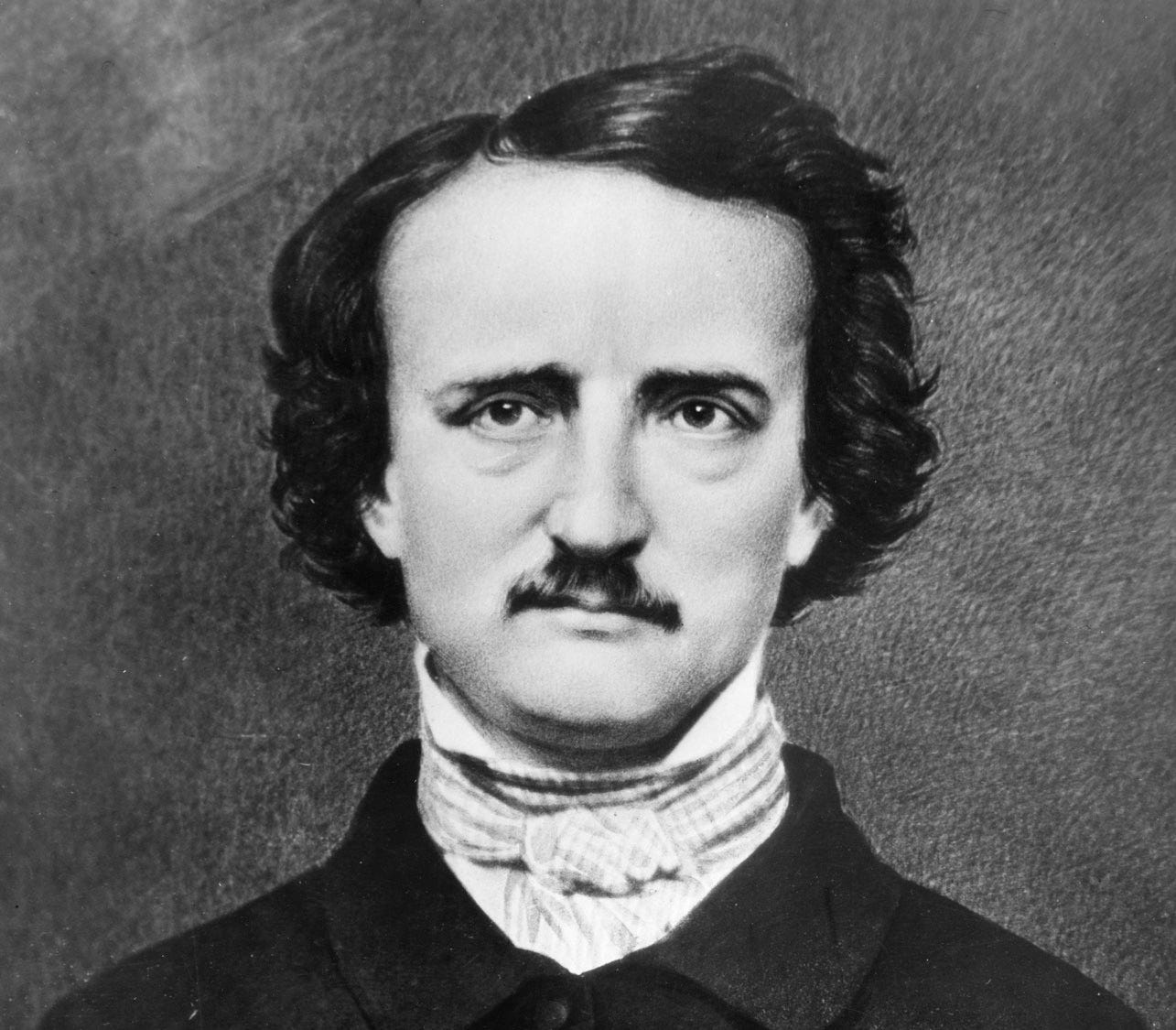

Edgar Allan Poe’s Eureka and the Big Bang

Did the 19th century master of the macabre predict our cosmic history?

Poe’s tales of terror have granted him a kind of literary immortality. Who could forget the horrific pit and pendulum, the masquerade ball of death, and the beating of the tell-tale heart? His poetry is also beautiful and very memorable.

Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Yet he had a little-known sideline — speculations about science. In his final work Eureka — A Prose Poem, published in 1848, one year before he died, Poe outlined some of his theories of the cosmos. His aims were most ambitious, especially for someone who lacked formal scientific training:

I design to speak of the Physical, Metaphysical and Mathematical — of the Material and Spiritual Universe — of its Essence, its Origin, its Creation, its Present Condition and its Destiny.

In Eureka, Poe painted a picture of a diverse, possibly infinite universe, speckled with countless stars, each composed of assorted atoms. This variety, he proposed, must have emerged sometime in the past from a far denser, unified state. Somehow, the primordial cosmic egg hatched into a remarkably diverse universe. As he wrote:

My general proposition, then, is this: In the Original Unity of the First Thing lies the Secondary Cause of All Things, with the Germ of their Inevitable Annihilation.

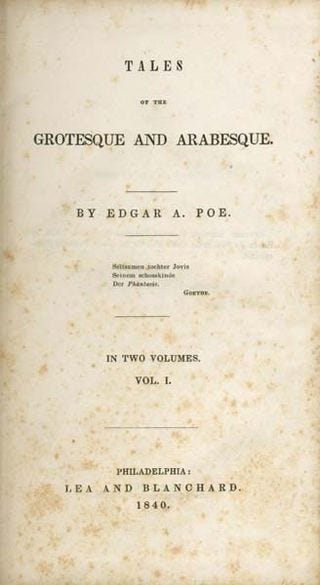

Heinrich Wilhelm Olbers, Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons; Lithograph by Rudolph Suhrlandt.

One of the curious riddles of Poe’s time, associated with one of its proposers, German astronomer Heinrich Wilhelm Olbers in the 1820s, was the question of why the sky is dark at night. Assuming that the universe was infinitely large and infinitely old, Olbers pointed out that if you trace any point of the sky far enough away from Earth, eventually you would reach a star. Therefore that star’s light would eventually reach us and illuminate that point. Because this would be true for all points in the sky, he concluded that it should be flooded with light, even at nighttime.

Image credit: James Schombert of the University of Oregon, via http://abyss.uoregon.edu/~js/ast123/lectures/lec15.html.

Why doesn’t midnight look like noon? Especially in those light-pollution-free times, nocturnal skies were cathedrals of darkness broken only by pinpoint stellar lanterns, not blazing spectacles. Horror writers and lamplighters counted on that. The House of Usher would look much less fearful if it were all lit up at night like Yankee Stadium. Luckily, for fans of the macabre, parts of the world are murky not gleaming. Therefore, Olbers’ paradox warranted sound explanation.

“Poe’s Tales of Mystery and Imagination” (1935) Illustrated by Arthur Rackham, Wikimedia Common

Poe phrased the riddle in the following way:

Were the succession of stars endless, then the background of the sky would present us a uniform luminosity, like that displayed by the Galaxy-since there could be absolutely no point, in all that background, at which would not exist a star.

Poe’s brilliant solution relied on three general principles. First, the speed of light is finite. As had been established in his day, he knew that light was very fast but not instantaneous — its speed could be measured. Secondly, space is enormous. Starlight would take numerous years to reach us — for some stars, maybe even thousands or millions of years. As he put this in Eureka:

The only mode, therefore, in which, under such a state of affairs, we could comprehend the voids which our telescopes find in innumerable directions, would be by supposing the distance of the invisible background so immense that no ray from it has yet been able to reach us at all.

Implicit in that final phrase is the third principle: the universe must be of a finite age. By stating that “no ray from [certain light sources] has been able to reach us,” Poe asserts that stars began shining a finite time in the cosmic past. Those might have been preceded by earlier stars, but far enough back in cosmic history, there were no shining stars, only darkness. The dark canopy of the sky represents all the places where no star has formed that is close enough for light to have reached us in the intervening time. Thus, the cosmos couldn’t be infinitely old, as Olbers had assumed.

Poe’s detective character C. Auguste Dupin, courtesy of Wikimedia Common

When Poe penned Eureka, the concept of a “day without yesterday” was mere speculation. Science had no proof that the observable universe had a finite age. Therefore, his prescient conclusion was an excellent example of the kind of proof by deduction a savvy detective would do — such as Poe’s famous fictional sleuth C. Auguste Dupin who employed deductive reasoning to solve mysteries.

Henrietta Leavitt, courtesy of Wikimedia Common

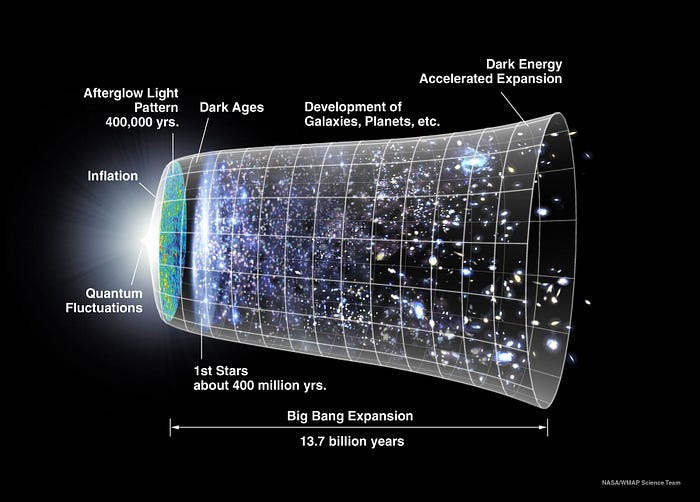

Poe, of course, could not have known that the Milky Way is but one of a multitude of galaxies, receding from us and from each other (except for our neighboring galaxies in the Local Group) because of the expansion of space. It would take the observational work of Henrietta Leavitt, Vesto Slipher, Edwin Hubble, and others, and well as the theoretical savvy of Georges Lemaître, to establish the general picture we now call the Big Bang. As cosmologist Edward Harrison demonstrated, the Big Bang theory elegantly explained Olbers’ Paradox by mandating that before a certain cosmic era, no stars would have existed. Therefore, the patches of darkness in the sky are regions where there has not been enough time for stars (or galaxies) to form and transmit their light to us.

Hubble Space Telescope, courtesy of NASA

With a powerful optical instrument, such as the Hubble Space Telescope, we’ve discovered far more visible objects breaking up the regions of true darkness. Supplement that device with radio receivers and other devices that capture all parts of the spectrum, and the sky is actually full of radiation — just not visible radiation. If our eyes were sensitive to radio signals, the sky wouldn’t seem dark at all, but rather a radio haze. Those radio waves constitute relic radiation leftover from the cosmic period called the Recombination Era, cooled by the expanding universe down to less than three degrees Kelvin. They can be seen through instruments such as the Planck satellite.

Timeline of the universe, courtesy of NASA/WMAP Science Team.

Poe imagined that the matter in the universe emerged from a greater unity, which was apt. However, he did not anticipate that it would be the expansion of space itself that caused such a transformation. Therefore, although Eureka is a highly imaginative work of great creative insight, it can hardly be said to have predicted the Big Bang.

On a personal note — related to the topic of cosmology — I’m greatly looking forward to Ethan’s upcoming book, Beyond the Galaxy: How Humanity Looked Beyond Our Milky Way and Discovered the Entire Universe, which is due out in October. I think it is amazing how much our understanding of the vastness of the observable universe has progressed in the past century, from just a single known galaxy to an estimated more than 100 billion. Awesome indeed, in the fullest sense of the word.

No comments:

Post a Comment