The take home is what we already know and that is to really go light on processed anything and restaurant meals.

I do think that brain damage does need to be noted as a long term progression for those who are unlucky. Particularly because i see no other obvious association. most known victims actually took care of themselves quite well. And good old MSG likely gets processed in the gut for most.

In short, the evidence is ambigous at best. We really need to identify direct biological pathways and good luck getting it right.

The dominant problem with processed goods is suppression of important nutriants. that is likely important. that is why i multi graze as much as possible.

Glutamate: A Neuron Killer in Disguise

This common ingredient that makes snack foods irresistible is linked to neurodegenerative disease

May 20 2023

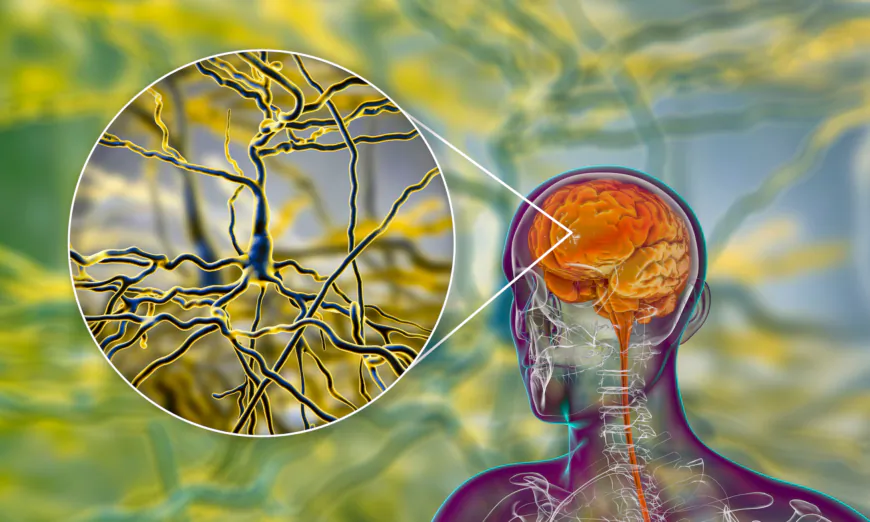

Human brain inside the body with closeup view of neurons, brain cells, 3D illustration

The discovery of glutamate more than a century ago was a milestone in the quest to make food as tasty as possible. Unfortunately, it took decades longer to learn that this amino acid is a critical neurotransmitter and that overeating it can have devastating effects.

Glutamate, in all its varied forms, has become a foundational additive in the so-called hyperpalatable processed foods we can hardly stop ourselves from eating—despite endless warnings to do so. Processed foods are a leading cause of disease, and many are almost irresistible because of the savory unami flavor bestowed by glutamate.

Glutamate’s most famous form—monosodium glutamate, or MSG—was discovered early on by the same Japanese chemist who discovered glutamate’s flavor-enhancing power.

In 1908, Kikunae Ikeda extracted glutamate from seaweed and sparked a multibillion-dollar flavor-enhancing phenomenon. Today, it’s widely used in potato chips, canned tuna, meat products, frozen meals, infant formulas, and other processed foods, and even in cosmetics and vaccines.

Consequences of Overconsumption

Significant research links the presence of too much glutamate in the brain to some of the most unsettling ailments of our day, including the neurological conditions of Lou Gehrig’s disease, multiple sclerosis, Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, Huntington’s disease, and others.

And avoiding it isn’t easy, since it hides under many different names, from its more chemical-sounding variants such as L-Glutamic acid or sodium glutamate, to far less obvious ingredients such as yeast extract, gelatin, textured protein, or soy protein isolate.

There are some important differences between these different kinds of glutamate, however, notes DrAxe.com, the website of Josh Axe, a clinical nutritionist and certified doctor of natural medicine.

Glutamate is naturally found in many foods, especially in meat and dairy. It’s a substance that occurs naturally in plants and animals. And in these natural states it’s bound together with other minerals, proteins, and compounds that help it move through the body without issue.

But the processed and synthetic forms of glutamate are different.

“Free glutamate … is the modified form that is absorbed more rapidly. The modified, free form is the type linked to more potential health problems,” DrAxe.com states.

Its widespread use means glutamate is consumed by people in most industrialized nations. MSG is consumed in amounts of 0.3 to 1.0 grams a day.

The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) established an MSG acceptable daily intake of 30 milligrams per kilogram of body weight, or about 2.1 grams for a 154-pound (70-kilogram) individual. Those who routinely eat processed foods likely eat far more glutamate than that amount.

While there’s some debate about the actual side effects of eating too much of the flavor enhancer, glutamate consumption is associated with adverse reactions. However, the EFSA noted that some studies support safe consumption of much higher levels than what was ultimately recommended.

Those recommendations and any insights about glutamate consumption, however, will depend heavily on the individual, for reasons we’ll explore.

Glutamate Means Go

It’s important to understand that glutamate, in and of itself, isn’t problematic. It’s when we have too much glutamate that problems arise.

Glutamate is a nonessential amino acid. In nutritional terminology, “nonessential” means that you don’t need to get it from outside sources, as your body has the ability to synthesize it through the impossible miracle of human biochemistry. Your body naturally produces it as a vital constituent of proteins.

Glutamate isn’t a small player in the body.

“Glutamate is the most abundant excitatory neurotransmitter released by nerve cells in your brain,” the Cleveland Clinic stated.

Neurotransmitters have a kind of yin yang duality, with some leading to an inhibited state in the receiving neuron, and some leading to an excited state in the receiving neuron. The body is in a constant process of trying to balance various systems amid every changing condition, ranging from temperature, to time of day, to stages in our life, and more. Glutamate is the most abundant “on” trigger in the brain.

“It plays a major role in learning and memory. For your brain to function properly, glutamate needs to be present in the right concentration in the right places at the right time. Too much glutamate is associated with such diseases as Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, and Huntington’s disease,” the Cleveland Clinic noted.

We eat both naturally occurring and man-made glutamate all the time. And glutamate isn’t just used in the brain. Once in the gut, specialized transport proteins shuttle glutamate into intestinal epithelial cells where it helps produce other amino acids and nucleic acids—the building blocks of DNA and RNA.

It’s also used to create the essential energy used by our cells, known as adenosine triphosphate, or ATP. The glutamate molecules that escape gut metabolism find themselves in the bloodstream, and that’s when problems arise.

Glutamate receptors aren’t just in neurons; they populate many of the organs of the body including the heart, kidneys, lungs, liver, and several others. When we have too much glutamate, it has access to glutamate receptors throughout the body, which act as switches that start or stop (depending on glutamate receptor type) specific cell activity.

Hence, there’s an association of MSG and glutamate with a host of health problems.

The Brain on Glutamate

As the Cleveland Clinic notes, too much glutamate is associated with some of the most devastating neurodegenerative diseases. Accessing the brain, however, requires leaping over an extra hurdle: the blood-brain barrier.

The blood-brain barrier acts as a finely tuned sieve to allow only necessary molecules through to our most sensitive organ. Studies conducted in mammals have been inconclusive about MSG’s ability to penetrate this barrier.

Most consumed glutamate is broken down in the gut. Beyond that, it has great difficulty overcoming the tightly knit cells surrounding the brain. But that isn’t always the case, and understanding that reality may make it prudent to question the amount of glutamate, including MSG, that the FDA and like institutions generally regard MSG as safe.

Science is conducted in more-or-less idealized scenarios to remove as many confounding factors as possible and better reveal the effects of the studied treatment.

That’s why experiments are often done in petri dishes using human cells, or in mice that have very specific characteristics.

But these conditions don’t truly mimic the immense variety of human bodies in the real world. People have a host of different diets, habits, ailments, medications, and biochemical states that are beyond anything scientific experiments can begin to account for.

An example is the emergence of gut issues, in particular leaky gut syndrome. These people suffer a kind of weakness along intestinal walls that can let substances out of the digestive tract and into the body, where they can cause a host of problems. Such people will likely be at greater risk of glutamate toxicity because the more they eat, the more will enter the bloodstream.

And even with the blood-brain barrier, glutamate may still enter the brain.

The blood-brain barrier doesn’t protect the entirety of the brain. The brain contains cerebroventricular organs designed to let substances in and out of parts of the brain so that the brain and body can communicate. For example, one such organ, the pineal gland, produces melatonin and helps to signal the body to go to sleep.

Like much of the body, cerebroventricular organs aren’t fully formed until puberty and can be weakened by fever, head injury, and aging. A 2010 study published in Brain Research revealed that MSG supplied directly into the bloodstream of newborn mice immediately enters the brain and induces seizures, which are the result of acute excitotoxic events. These findings specifically call into question the wisdom of adding MSG to infant formula.

Because glutamate is the primary excitatory neurotransmitter in the brain, glutamate is the brain’s major signaling molecule. Glutamate exerts its excitatory function by instructing other neurons to release their neurotransmitters in a process known as neurotransmission. Excessive, uncontrolled glutamate in the brain can beget excessive, uncontrolled neurotransmission, which can cause major health problems.

Glutamate neurotoxicity results from neurons being in an “on” state for too long. The received glutamate signal from outside the neuron causes calcium levels inside the neuron to increase. Too much calcium inside the neuron activates proteins that degrade other proteins and lipids, eroding the integrity of the neuron’s structure.

To compensate, the neuron’s energy factories, the mitochondria (which exist in all cells), absorb the excess calcium. Once the mitochondria are overwhelmed, however, they begin to shut down and leak molecules, which truly signals the end for the neuron. What follows is generation of a diverse cadre of damaging reactive oxygen species and a state of neuron death. If this occurs in a large enough swath of brain cells, lesions can develop, which can result in disease.

A 2021 study in Frontiers in Neuroscience details the ability of MSG (and presumably all free-form glutamate) to cause the studied protein to lose its shape and to aggregate. Correct shape is required for the proper function of any protein. Protein aggregates are an accumulation of many copies of the same protein type, which, should they grow large enough, become difficult for the cell to deal with and have the potential to kill the cell—and spread the protein aggregation effect to nearby cells.

Though the researchers investigated MSG’s effect on bovine serum albumin, a carrier protein abundant in the blood of cows, they acknowledge the potential of this MSG protein aggregation phenomenon to extend into neurodegenerative diseases.

Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, Lou Gehrig’s, and Huntington’s diseases are all associated with an overabundance of protein aggregation-induced neuron death in specific brain regions.

A 2019 study published in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease analyzed the response of oral administration of MSG to mice susceptible to Alzheimer’s disease. It was found that the molecular markers of Alzheimer’s disease appeared earlier, and the capacity for memory formation was further impaired in the mice that were orally given MSG.

Processed foods are a leading cause of disease and many are almost irresistible because of the savory unami flavor bestowed by glutamate. (Hamza NOUASRIA/Unsplash)

How to Avoid MSG Toxicity

The surefire way not to be poisoned by free-form glutamate (MSG and its kin) is to avoid processed foods and the restaurants that use them (which is basically all of them). Instead, base your diet on whole foods such as organic fruits and vegetables, as well as meats and dairy from grass-fed animals.

If you do down a bag of chips or an MSG-laden meal and want to minimize any consequences, a study published in Nutrients found garlic powder to be effective at counteracting the brain ravages of MSG.

In addition, curcumin, lycopene from tomatoes, green tea extract, gingerols and shogaols from ginger, rosmarinic acid in rosemary, quercetin, and vitamins C, D, and E all negate much of the oxidative damage and cell death caused by free-form glutamates such as MSG in the body, according to a research review published in the Iranian Journal of Basic Medical Sciences in 2020.

Naming Glutamate

Here are a few forms of synthesized, or free-form glutamate, you may see on your snack’s ingredient label:Monosodium glutamate or sodium glutamate

Sodium 2-aminopentanedioate

Glutamic acid, monosodium salt, monohydrate

L-Glutamic acid, monosodium salt, monohydrate

L-Monosodium glutamate monohydrate

Monosodium L-glutamate monohydrate

MSG monohydrate

Sodium glutamate monohydrate

UNII-W81N5U6R6U

Flavor enhancer E621

No comments:

Post a Comment