All very nice and does work in the correct locations. That is the problem. virtually the entire coast is exposed to churning seas at best and this must be avoided or protected from. Protection really means an off shore weir large enough to control incoming wave action.

The low tidal stroke of the tropics works very well for this. Yet then we have incoming storm surges. Sooner or later, we have a wreak. So not so easy.

The other thing that must be addressed is combining land title with economic viability. All this also needs to make resident land grabs uneconomic as well. Every mile of beach needs to be taxed as if it is commercially exploited to discourgage ownership by assumption or to remove it from existing free title.

The Genius of Fishing with Tidal Weirs

Native and non-native scientists have come together to counter overfishing with an ancient practice.

BY KATA KARÁTH

April 6, 2022

https://nautil.us/the-genius-of-fishing-with-tidal-weirs-15894/

Seen from the air, the Micronesian state of Yap is a jewel-green archipelago of dense forests patched with taro fields, fringed by mazes of mangroves, and trimmed by coral reefs. And, fanning out from the wrack lines into the turquoise shallows like a frill of beaded tassels is a geometric design of rock structures that are shaped like arrows, beech mushrooms, or penises. The Yapese call these structures aech, and they are tidal fish weirs, one of the world’s most common Indigenous mariculture tools.

“Our aech is called Aechwol because of its luck,” says Thomas Ganang, whose family has owned for generations an aech near the village of Gachpar, off the eastern shore of Gagil-Tamil Island; in Yapese, “wol” means “luck.” “Whatever fish I catch inside the aech is a sign of luck. So it’s an ‘aech with good luck.’” Ganang, who is 66, fondly recalls how, when he was still a boy, his father, Laman, took him to the faluw—a traditional men’s house in Yap—to teach him everything about fishing, including how to use aech.

GONE FISHING: A fishing weir in the Micronesian state of Yap. The “arrow” of stone walls traps fish at high tides. When the tide ebbs, fishermen go to work. Photo courtesy of William Jeffery.

The mechanics of tidal weirs are simple: They are made of walls, varying in shape and size. (In Yap, weir walls are built of stone, but in other regions of the world a traditional weir can have a stone base with temporary wooden structures built on the top, or it can be made entirely out of wood.) High tide submerges these walls, letting fish swim within them freely, but as the tide ebbs, the fish gets trapped in the chambers. Then, fishermen—in Yap, traditionally, fishing is a man’s task—can use butterfly nets called k’ef to catch fish, or herd it toward weir baskets woven of split green bamboo stalks laced with coconut cord, which are submerged and attached to the end points—the arrowhead’s barbs—of the aech. If fishermen are looking for a bigger catch for a community event, they use leaf brooms made of coconut fronds twisted about a long rope to herd the fish into weir baskets or nets.

More than 800 tidal weirs, between 65 to 650 feet in length,are scattered across the four islands that make up Yap, according to William Jeffery, an Australian-born marine archaeologist at the University of Guam, some 500 miles north of Yap. In 2008, the group of Yap Main Island traditional chiefs known as the Council of Pilung, along with the Yap Historical Preservation Office, hired Jeffery to survey all of Yap’s surviving and undocumented tidal weirs. The survey took place between 2008 and 2009, and was made possible by grants from the U.S. Historic Preservation Fund, which finances projects focused on heritage conservation. Jeffery has continued his research on Yap, though his field research has been interrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic. So far, he and his colleagues have mapped about 450 tidal weirs, and about 50 of them remain in use.

Western-trained scientists are beginning to acknowledge what Indigenous practitioners have known for thousands of years.

Like many forms of Indigenous mariculture worldwide, fishing with aech has fallen out of use for a variety of reasons that range from colonialism, moving away from sustenance to commercial fishing, the accessibility of modern fishing gear, urban migration, globalization of food supplies, and simply loss of interest. The Council fears that, since fishing with aech is no longer a common practice that is passed down to younger generations, the ancestral knowledge related to the aech construction and use will be lost.

The Yapese are not alone in their endeavor. In the last two decades, from the aechs in Yap to clam gardens throughout the Pacific Coast of North America, the revitalization of Indigenous mariculture is making headway across the globe. As the world confronts the ways in which extraction is decimating the planet’s resources, Western-trained scientists are beginning to acknowledge what Indigenous practitioners have known for thousands of years: The survival of humanity is intertwined with the health of our ecosystems and how we manage our resources. Traditional management of marine resources tends to have sustainability built into its core, perfected over millennia of trial-and-error and occasional climate adversity. “In an aech, you can see which fish you want to catch, and set a limit on how much is enough to feed the family,” says Ganang. “Modern nets catch all sizes of fish, small ones can get stuck and tangled. It kills them all.”

In many parts of the world where this knowledge has faded, native groups, frequently pairing up with native and non-native scientists and environmentalists, now seek to restore ancient practices to protect these ecosystems and the communities. Akifumi Iwabuchi, a maritime anthropologist at the Tokyo University of Marine Science and Technology, heads an international network of researchers investigating the role tidal weirs play in conservation. His research is part of the United Nations Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development. Tidal weirs were designed to avoid or minimize overfishing, and even encourage fish breeding, Iwabuchi explains. In the weirs, the gaps between the rocks allow young, small fish to pass through effortlessly, while predators are kept outside. Large fish become trapped in the weir, so fishermen only harvest adult fish. Growing scientific evidence suggests the weirs and other Indigenous mariculture methods act as “artificial wombs for marine species,” Iwabuchi says. That leads to an increase in the local biodiversity that can safeguard marine ecosystems and those who rely on them in the face of climate change and future pandemics.

Indigenous communities currently manage more than 40 percent of Earth’s ecologically intact landscapes. As industrialization and climate change continue to deplete marine resources while fish consumption is on the rise, there is an urgent, worldwide need for sustainable fishing and aquaculture. Since 1961, global fish consumption has increased at an average of 3.1 percent each year—a rate twice as high as the annual world’s human population growth for the same period, according to a 2020 report by the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization. Meanwhile, the percentage of fish stock caught at biologically unsustainable levels has more than tripled, from 10 percent in 1974 to 34.2 percent in 2017.

The ingenuity of tidal weirs in Yap and around the world—from the kaki in Japan’s Okinawa island to the hadra in Kuwait’s Failaka island, the wooden fish weirs along the French coast of Brittany to the corrales de pesca in Chilean Patagonia—lies in their simplicity. Indigenous coastal communities, based on their accumulated knowledge of local ecosystems, have adapted the weirs to particular coastal topographies and seascapes.

OCEAN RENEWAL: Members of the Heiltsuk Nation in British Columbia recently built this fishing weir using traditional methods. Photo by Bryant DeRoy.

The Yapese believe that the aech represent a harmonious relationship between humankind and the ocean. The first seven aech, the Yapese say, were built more than 1,500 years ago by spirits who assumed the form of men, women, or eels, to show humans how to construct the weirs and learn how to fish in a sustainable manner. But the details of the aech origin tale have eroded over time. “All I know is that this aech belonged to [my father] Laman,” says Ganang. “Most of the stories and legends of this aech are long gone.”

The Yapese fishermen’s knowledge of sea currents and tides and of fish behavior, migration, and population dynamics have allowed them to fine-tune their aech to perfection and practice sustainable fishing for generations. Fish are caught at specified times, for only a few days in a given month. Outside of these specific days, Yapese fishermen told Jeffery, they make an opening in the aech to let fish come and go so that they “feel at home.” The fishing schedule, says Ganang, depends on the time, season, or weather.

Sustainability practices are often woven into Indigenous traditions and ceremonies. The majority of Indigenous salmon fishing communities from California to Alaska hold some form of what they call the First Salmon Ceremony to this day, to honor the life-giving salmon. While the particulars of the ceremony differ from culture to culture, each community imposes a short-term moratorium on fishing following the event. This break allows the first runs of salmon to reach their spawning grounds before fisheries resume operating. “The only harvesting that happens” during the moratorium “is by the bears and the wolves and the eagles,” says William Housty, a member of the Heiltsuk Nation who works at the Heiltsuk Integrated Resource Management Department, which oversees land and marine resource management within Heiltsuk Territory in British Columbia.

The Yapese believe that the weir represents a harmonious relationship between humankind and the ocean.

Catches from tidal weirs play a significant role in communal health. Freshly caught fish and other seafood are higher in nutrients than imported, processed food. Fishing with tidal weirs is often carried out by multiple families, so that the catch could be shared, and, historically, during hard times such as epidemics, typhoons, drought, or famine neighboring villages supported each other. The COVID-19 pandemic has already put some Indigenous mariculture techniques to a contemporary test and proved them to be a source of resilience. A recent study published in Marine Policy demonstrated that most rural Pacific communities had managed to ensure food security in the early months of the pandemic thanks to traditional practices of local food production and food sharing.

Indigenous mariculture practices can nurture not only the body, but also the spirit. “One important goal is providing opportunities for community members to connect with one another, and to tell stories on the beach,” says Melissa Poe, an applied environmental social scientist at Washington Sea Grant, which is dedicated to coastal and marine research, outreach, and education in Washington state. “So as much as we focus on the productivity of seafood and marine life, there are also really important embedded cultural and social goals to some of the recovery of these systems.” Harvesting traditional foods and sharing stewardship knowledge through generations is fundamental to Indigenous cultural identity and helps strengthen communities’ connection to a place. Many of these seafoods are emblematic of Indigenous cultures, like salmon for the Heiltsuk, Nisga’a, Wuikinuxv, and other coastal First Nations in British Columbia, seaweed for the Waimānalo Limu Hui in Hawai’i, or mullet for Japanese coastal communities.

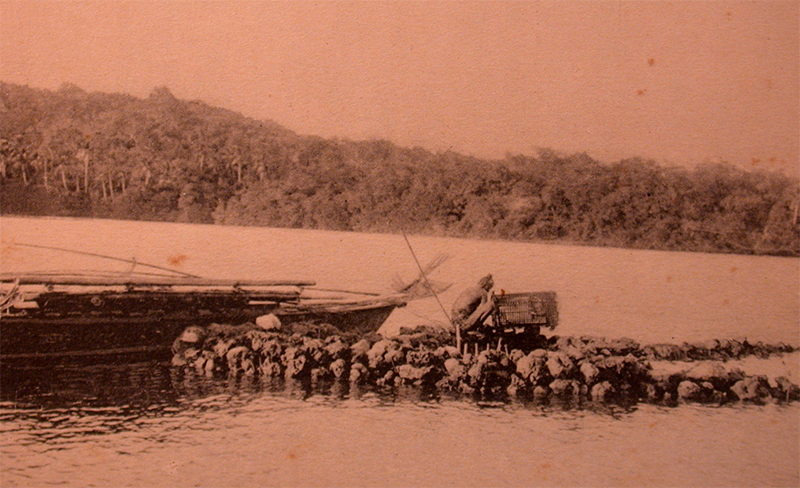

TIME-HONORED TRADITIONS: A fisherman sets a trap on a stone weir on Yap in 1908. Photo courtesy of William Jeffery.

In China, says Iwabuchi, some coastal communities in Hainan Island and Fujian Province have been singing songs that incorporate traditional ecological knowledge about the relationship between tides and the phases of the moon. “Local people using a stone tidal weir knew that song, and passed it down generation to generation,” says Iwabuchi. Some communities along the northwest coast of Hainan Island still use such songs to guide them not only when using tidal weirs, but also other traditional offshore fishing activities. Unfortunately, says Iwabuchi, there haven’t been any initiatives to revive neither the stone tidal weirs nor the tidal songs. “When stone tidal weirs disappear completely, such songs will go extinct.”

A number of factors are responsible for weirs’ decline. The colonization of Micronesia began in 1521, depositing at its shores an ever changing array of invaders from Spain, Germany, Japan, and the United States over the next 500 years. The people of Yap suffered particular hardship, primarily from diseases that colonists imported from overseas; the island’s population dropped from about 40,000 people pre-contact to 2,500 immediately after World War II. (The population has rebounded to around 12,000 people today.) Jeffery and other researchers believe that a drastic population decline meant that there was no need for large catches, and the labor-intensive use of tidal weirs was no longer justified. Japanese colonizers, who occupied Yap primarily between the two World Wars, forced the Yapese to speak Japanese, and changed their social structures through banning them from leadership positions, prohibiting traditional religious practices, and destroying traditional council meeting sites, such as men’s houses like the one where Ganang’s father taught him about weir fishing. The aech were no exception. “It was a ready supply of rocks that [the Japanese] could use for other building purposes,” Jeffrey says.

First Nations along the Pacific Coast have begun building fish weirs again. Modern technology has come in handy.

Similar scenarios played out across the U.S. and Canada, where colonial policies severed access to sustainable salmon fisheries and other mariculture practices. Entire populations were forcibly removed from coastal areas. Between 1904 and 1905, the Canadian government forcibly removed fish weirs in the Babine River watershed in British Columbia, disrupting millennia of Indigenous management of Babine salmon. “At one point in time, it was illegal for an Indian to own a fishing license,” says Housty, whose grandmother still used stone fish weirs in the 1930s. The industrialization of fishing and urban migration prevent the robust recovery of traditional mariculture.

Still, over the last two decades, a growing number of coastal First Nations along the Pacific Northwest Coast of North America have begun building or restoring fish weirs, placing them at estuaries or even higher up the rivers. Modern technology came in handy: “The first weir that we actually put together was from western red cedar,” says Housty. “It was a species that were utilized by our ancestors because of how unique it is. Our canoes were carved from it, all of our houses, and even some of the traditional clothing was [woven] from the bark of the cedar.” But after each heavy rain, the Koeye River kept sweeping away the wood, and the Heiltsuk switched to aluminum.

Putting decisions about mariculture in the hands of local leadership can push for more equitable fishing opportunities for both Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities. Examples include the Hui Mālama Loko Iʻa, a growing network of fishpond practitioners and organizations in the Hawai’ian archipelago working on the revival of loko iʻa, which encompasses various types of traditional Hawai’ian fishponds. The network currently consists of over 40 fishponds and complexes that are managed by more than 100 loko i’a owners, workers, and stakeholders.

Some tidal weirs and other Indigenous mariculture practices also help turn the tide on colonial disenfranchisement of Indigenous populations. In Japan and Yap, local groups have rebuilt tidal weirs not just for fishing, but to preserve the traditional ecological knowledge that comes with it, and so boost cultural tourism and environmental education. In British Columbia, Indigenous salmon fisheries double as monitoring stations for scientists and help advise Indigenous and federal fishery management policies. Among various traditional practices, fish weirs help fisheries to measure, tag, release, and later recapture salmon, which provides invaluable data to assess fish stocks, plan and adjust harvest levels, and determine factors limiting salmon reproduction. The Heiltsuk Nation, Housty says, currently uses its weir only for scientific research. “When we’re able to better predict what more sustainable cut-offs are in terms of escapement, then we may be able to take some of the fish that go through and distribute them in the community.”

The renaissance of Indigenous mariculture hasn’t been without challenges. In Yap, there aren’t many people left who actually know how to build aech. The Yapese government’s early attempts to restore aech in 2005 and 2006 were not very successful. “It didn’t take long before they were knocked down,” says Jeffery. “The Yapese told me they were not rebuilt in a good traditional manner.” Figuring out how to build aech properly was another reason why the Council of Pilung wanted Jeffery to survey sites and interview aech owners. Money and labor capacity can be an issue. As of today, The Yapese Historical Preservation Office has only managed to restore a single aech. It cost $2,000, and it took 3 months for a crew of 11 men to rebuild it.

Bureaucracy can also stand in the way. Housty says the Canadian Department of Fisheries and Oceans at first treated their fish weir project with a lot of skepticism. He believes they were worried that the firsthand, scientific data the weir was going to bring in would contradict some of the management decisions they had made over time. And over the nine years since the first weir was installed, Housty says, “[we] effectively have blown the Department of Fisheries and Oceans out of the water in terms of data that we have, making decisions not based on models that someone on a computer made.”

Meanwhile in Yap, Ganang and his family cannot fish at Aechwol at the moment. As of 2016, 12 percent of Yap’s near shore marine areas are part of a network of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs), and Aechwol happens to be in one of them. “So now it is just for show,” says Ganang. This might change in the future, as there is an interest in incorporating the traditional ecological management that comes along with the use of stone tidal fish weirs into the management of MPAs. Conflict between recovering traditional aquaculture methods and marine conservation is playing out in other regions, too: On the island of Moloka’i, for example, Hui Malama O Mo’omomi are pushing Hawai’i state legislators to recognize their plan to uphold the conservation of the Mo’omomi Community-Based Subsistence Fishing Area, which would allow Native Hawai’ians to harvest fish in Mo’omomi Preserve, the last stronghold of a major Hawaiian coastal ecosystem.

Ganang says his son who lives in the U.S. has only seen photos of aech on the internet, but he is keen to learn how to fish with them. “To me, it is like a tool, like an axe. It eases the work,” says Ganang “When I fished with the aech and I would see a rock fall out of its place, I would repair it as it is something that helps me, so I took care of it.” Until the legalities around traditional fishing within an MPAs are finally untangled, Ganang can only watch from the shore as the fish feel at home in his aech.

No comments:

Post a Comment