what makes this extensive article so annoying is that it totally avoids talking about vitimin C or ascorbic acid. We are all staving of scurvy which brings about bone degeneration in the first place.

Lots of good information here, but it will not counteract scurvy. Our bodies do not make it and all mammels do. we truly need to be agressive about it.

Circulatory disease and osteoporosis are caused directly by scurvy and nothing else that matters. all proven decades ago ,but do ignore the science.

I also know that you are so unconfident in yourself that you will not listen. I use a teaspoon of ascorbic acid in a tea made from grapefruit peel extract. It works and everything else merely slows the damage.

The Essential Guide to Osteoporosis: Symptoms, Causes, Treatments, and Natural Approaches

FEATUREDOSTEOPOROSIS

Jul 30 2023

Osteoporosis is a "silent" disease that you may not detect until you fracture a bone. (The Epoch Times)

Osteoporosis, meaning “porous bones,” is a medical condition that causes bones to become weak and brittle. As a result, minor falls and mild movements such as coughing or bumping into furniture may cause bones to fracture.

Osteoporosis is a “silent” disease, as patients may not notice its symptoms until they fracture a bone. Osteoporosis-related fractures often occur in the hip, spine, rib, leg, pelvis, and wrist, although any bone can fracture except the skull.

In addition, osteoporosis hampers bone healing, leading to persistent pain following fractures. Fractured hip and spine bones are particularly critical, resulting in decreased mobility and independence for older adults.

As the most common metabolic bone disease, the worldwide osteoporosis prevalence is 18.3 percent.

What Are the Common Types of Osteoporosis?

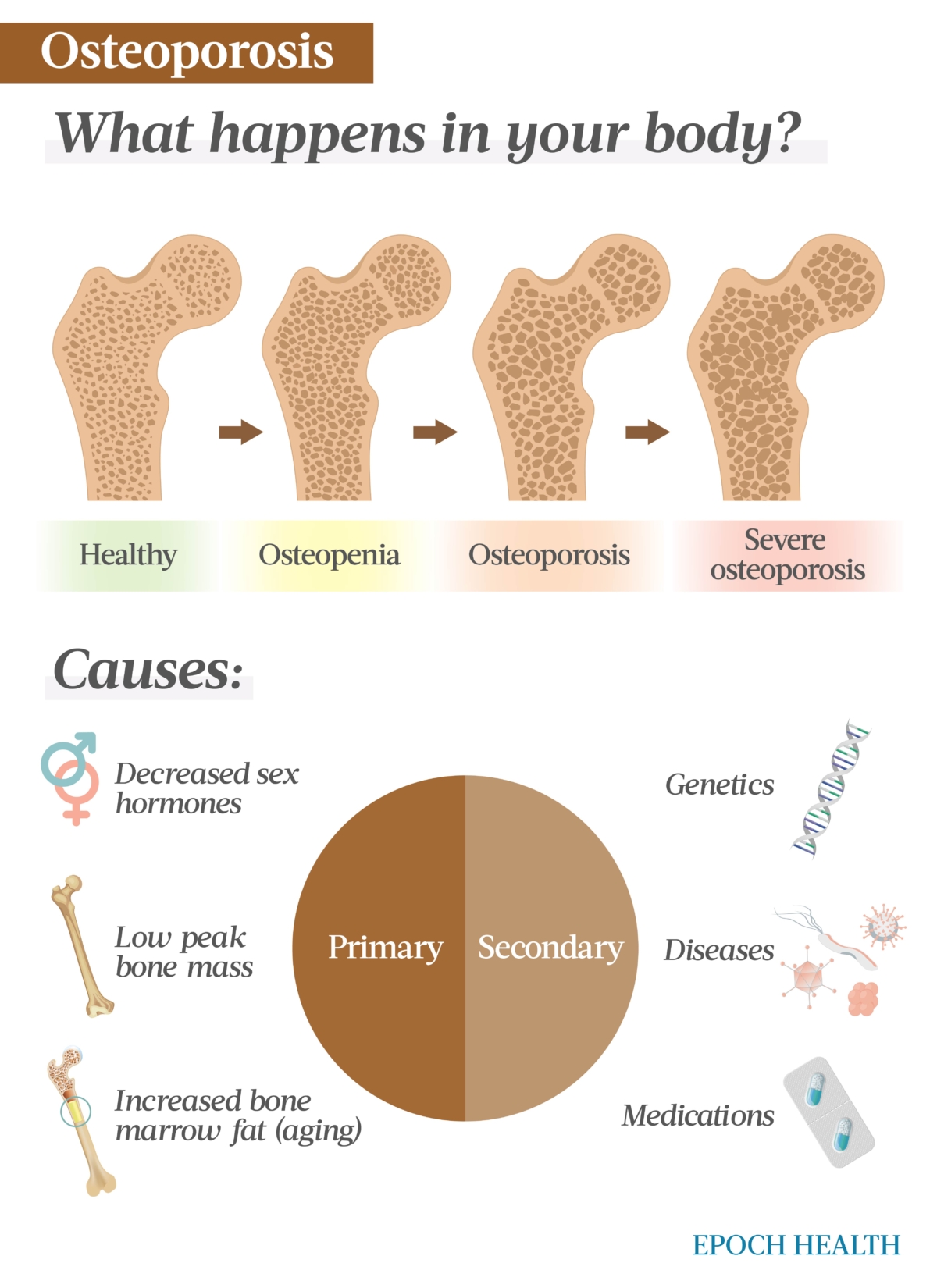

There are two categories of osteoporosis.

1. Primary

Primary osteoporosis is the most prevalent form and encompasses two types:

Postmenopausal osteoporosis (Type 1): This type of osteoporosis results from the drop in estrogen and progesterone levels around menopause. On average, women experience a loss of approximately 10 percent of their bone mass within the initial five years following menopause.

Senile osteoporosis (Type 2): Also referred to as age-related osteoporosis, this is gradual bone loss initiated by the decrease in stem-cell precursors, which, as we age, play a crucial role in bone formation.

2. Secondary

Secondary osteoporosis is caused by medical conditions, such as hyperthyroidism and Cushing’s disease, injury, or certain medications. The treatment for secondary osteoporosis is more complex than primary, as the underlying disease or condition must first be addressed.

A bone loss condition occurring before osteoporosis is called osteopenia, characterized by lower bone mineral density (BMD) than the average of others within the same age group. With treatment and individual risk factors, such as lifestyles and dietary/exercise habits, osteopenia may or may not result in osteoporosis.

When osteoporosis is not treated correctly, it may deteriorate into severe osteoporosis. A patient with severe osteoporosis may experience bone fractures from coughing or sneezing due to very fragile bones.

What Are the Symptoms and Early Signs of Osteoporosis?

As aforementioned, there are usually no obvious symptoms or pain in the early stages of osteoporosis. Later, when the skeleton has been weakened by osteoporosis, a patient may experience the following symptoms:Gradual loss of height due to a broken or collapsed vertebra.

Change in posture, such as stooping or a hunched back, due to broken spine bones.

Back pain, sometimes felt suddenly, which may be caused by compression fractures in the spine.

Brittle nails.

Reduced hand-grip strength.

Shortness of breath due to a reduced lung capacity caused by compressed disks.

Since osteoporosis typically develops gradually, its first noticeable sign is often a bone fracture. If you experience the above symptoms or have a family history of osteoporosis, you should consult your physician to assess your risk.

What Causes Osteoporosis?

The underlying cause of osteoporosis is always a disruption in the balance between old bone breakdown and new bone formation, with a decreasing bone mass. As our bones contain essential minerals, they constantly break down to release the minerals into the bloodstream in a process called bone resorption, then are replaced with new bone tissue. When new bone formation doesn’t keep up with the old bone loss, bones become porous and brittle with less density and strength, thus possibly leading to osteoporosis.

Most people reach their peak bone mass, their largest bone size and density, between 25 and 30 years old. After age 40, we typically lose bone mass faster than it’s generated. At first, the rate of bone loss is approximately 0.3 to 0.5 percent per year in both sexes. However, in women, this rate escalates after menopause, reaching an annual rate of 2 to 3 percent. After approximately a decade, the bone loss rate reverts to a lower level.

Peak bone mass is also a predictor of the future risk of osteoporosis. The higher your peak bone mass, the lower your risk of having osteoporosis.

Although the underlying cause of osteoporosis is the same, the factors contributing to each type can vary.

Postmenopausal Osteoporosis

Menopause in women leads to a decline in estrogen levels, as the ovaries produce significantly less estrogen. Since estrogen plays a vital role in inhibiting the activity of bone-resorbing cells, estrogen deficiency can lead to enhanced bone resorption over formation, causing accelerated bone loss.

The reproductive hormone progesterone promotes bone formation, and as its production also significantly decreases at menopause, so does the production of new bone tissues.

Additionally, the decrease in ovarian inhibin B and elevated follicle-stimulating hormone levels during the menopause transition also contribute to changes in bone turnover.

Due to the effects of these hormone changes and other factors, by the time a woman reaches the age of 70, there is typically a decline in bone mass of approximately 30 to 40 percent.

Senile Osteoporosis

As people age, it is natural for bone density and strength to decrease gradually. The aging process leads to the deterioration of bone composition, structure, and function, making individuals more susceptible to osteoporosis.

Age-related bone loss is characterized by a significant increase in bone marrow fat accumulation, which occurs at the expense of the formation of new bone cells. Elevated levels of bone marrow fat are linked to decreased bone density and an increased prevalence of vertebral fractures.

According to one study, the bone marrow fat content was around 29 percent in young women. In older women, the bone marrow fat content varied based on their bone mineral density (BMD). The marrow fat content was about 56 percent for those with normal BMD. In women with osteopenic BMD, the marrow fat content was around 63.5 percent, and in those with osteoporotic BMD, it was about 65.5 percent.

In men, declining testosterone levels with age can also contribute to bone loss and increased risk of osteoporosis, as the hormone is crucial for maintaining BMD.

Secondary Osteoporosis

Secondary osteoporosis can occur due to various medical conditions or the utilization of specific medications.

The diseases that can cause osteoporosis include:Genetic disorders (e.g., cystic fibrosis).

Endocrine disorders (e.g., Cushing’s syndrome, hyperparathyroidism, and Type 1 diabetes).

Gastrointestinal diseases (e.g., Inflammatory Bowel Disease and celiac disease).

Hematologic disorders (e.g., hemophilia and leukemias).

Bone cancer and cancers that can spread to the bones.

Liver diseases, such as liver cirrhosis.

COVID-19 requiring hospitalization, of which secondary osteoporosis may be a post-acute sequela.

The medications that can cause osteoporosis include:

Glucocorticoids (aka corticosteroids).

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), which are acid suppressants.

Anti-epileptic drugs.

Medroxyprogesterone acetate.

Aromatase inhibitors (e.g., letrozole, anastrozole, and exemestane), which block the production of estrogen in the treatment of breast cancer.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) (e.g., fluoxetine and sertraline), a class of antidepressants.

Chemotherapy agents (e.g., methotrexate).

Anticoagulants (e.g., heparin).

Calcineurin inhibitors as immunosuppressive drugs to prevent organ transplant rejection (e.g., cyclosporine and tacrolimus).

Thiazolidinediones (e.g., rosiglitazone and pioglitazone) treating Type 2 diabetes.

Osteoporosis can be caused by primary or secondary factors. (The Epoch Times)

Who Is More Likely to Develop Osteoporosis?

Many other factors can increase the risk of developing osteoporosis.

Unmodifiable FactorsAge: The older you are, the higher your risk of osteoporosis. Older adults may also experience nutritional deficiencies that can impact bone health. For instance, inadequate intake of essential nutrients such as calcium, vitamin D, and protein can compromise bone density and strength.

Sex: Twenty percent of women over 50 have osteoporosis in the United States, while the prevalence among American men over 50 is about 5 percent. Although women are more prone to osteoporosis, men are more likely to die within the year following a hip fracture. As per a study, men had a twofold higher likelihood of mortality during the first and second years after hip fracture than women.

Race: White and Asian people are at higher risk than black or Hispanic people. Although white women are more prone to osteoporosis than black women, the latter have a comparatively higher likelihood of mortality (pdf) following a hip fracture.

Skeletal frame: Petite and thin individuals have a higher risk of developing osteoporosis than those with greater body weight and larger bone frames because individuals with smaller frames have less bone mass to draw from, making them more susceptible to bone loss.

Family history: If you have family members with osteoporosis, you have a higher risk of developing osteoporosis, as primary osteoporosis is affected by genetics.

Modifiable FactorsBody mass index (BMI): Low BMI (i.e., low body weight) is a modifiable risk for osteoporosis. According to a Korean study, with every 1 kg/m² increase in BMI, the risk of osteoporosis decreases by 28 percent in men and 13 percent in women.

Physical activity: The more sedentary your lifestyle, the greater your risk of osteoporosis.

Alcohol consumption: Three or more alcoholic drinks daily can increase the risk of osteoporotic fractures.

Smoking: Tobacco use disrupts the balance of bone turnover, resulting in decreased bone mass and rendering the bones more susceptible to osteoporosis and fractures.

Diet: Poor eating habits can result in inadequate essential nutrients, such as protein, calcium, and vitamin D, crucial for maintaining strong and healthy bones.

Other Factors

Specific cancer treatments can increase the risk of osteoporosis, including:

Chemotherapy that induces early menopause.

Radiotherapy that renders the ovaries ineffective.

Surgery to remove the ovaries before menopause (breast cancer treatment).

Hormone therapy that lowers either estrogen or testosterone in the body (breast and prostate cancer treatments).

Various diseases, conditions, and medical interventions—some modifiable and some not—can increase the risk of osteoporosis, including:Low levels of sex hormones due to menopause, old age, or surgical removal of the ovaries or testicles.

How Is Osteoporosis Diagnosed?

Individuals who should get tested for osteoporosis include:Women over 65, as per the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force.

Postmenopausal women under 65 but who are at an increased risk of osteoporosis.

Women experiencing early menopause.

Men over 70, as per the National Osteoporosis Foundation (NOF).

Individuals over the age of 50 with a bone fracture.

Individuals suspected of having osteoporosis due to the intake of osteoporosis-inducing medications or a family history of osteoporosis.

It is essential for a health care professional first to examine your medical history, perform a physical examination, and investigate potential causes of secondary osteoporosis, which may include medical conditions or the use of medications known to be associated with osteoporosis. This screening process can involve blood tests and urine tests.

Afterward, your doctor can order a bone density scan if he or she thinks you may have osteoporosis or are at risk of developing it.

Tests

Among the current methods to measure BMD, dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA or DXA) is the most commonly used.

DEXA scans use low radiation to determine bone density in the spine, hip, or wrist, the three areas most vulnerable to osteoporosis. Specifically, they utilize both a high- and low-energy X-ray beam simultaneously; the entire process takes three to seven minutes. These tests, also called bone densitometry, can detect bone health issues before symptoms become apparent.

DEXA compares your bone density to that of a healthy 30-year-old, providing a T-score and a Z-score.

A T-score of -1 or higher is considered normal bone density, while a T-score between -1 and -2.5 indicates osteopenia. A T-score of -2.5 or lower indicates osteoporosis. Every one-point drop below zero in the T-score doubles the risk of bone fracture.

The Z-score compares your bone mass with individuals of the same race, age, and sex. This score is used if you are under 50 years old.

Your doctor may use the BMD results and other screening tools, including questionnaires and ultrasounds, to estimate your risk of fractures, including hip fractures, over the next 10 years, considering bone density and other risk factors such as family history and lifestyle.

As recommending DEXA may not be practical or cost-effective for all individuals, other tests and tools may be available, although they are less common.

Single-energy X-ray absorptiometry (SXA) is similar to DEXA but uses a single-energy X-ray beam to measure bone density. SXA measures bone density in the heel and forearm but is not as commonly used as DEXA.

Radiographic absorptiometry (RA) is a bone mass measurement technique utilizing radiographs of peripheral sites, such as the hand or heel. It gained popularity in research during the 1960s but was later replaced by non-radiographic densitometry techniques. The bone mass and fracture risk measurements are comparable to other bone mass measurement methods, thus making RA an attractive option for osteoporosis diagnosis due to its low cost and minimal need for specialized equipment.

Quantitative computed tomography (QCT) is a test to measure BMD using a CT scanner to produce a 3D image. QCT evaluates mainly the hip and lumbar spine to assess bone density. Safe and reliable, QCT is an alternative method for people who cannot undergo a DEXA scan for various reasons.

Quantitative ultrasound (QUS) is a less expensive and more accessible method to assess bone density than DEXA scans. It can be performed on various parts of the skeleton, such as the heel and forearm. However, there are still uncertainties about its use because different QUS models may generate different results. However, QUS can be helpful when central DEXA (i.e., a hospital-based scan) is not readily available. For now, using QUS alongside other risk factors to assess fracture risk and not rely solely on QUS for treatment decisions or follow-up. As the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of osteoporosis thresholds cannot apply to QUS, more research is needed to set specific thresholds for QUS devices.

Online questionnaires can combine your bone density test with other relevant factors for your doctor to estimate your risk of experiencing a fracture within a period. Examples include Fracture Risk Assessment Tool (FRAX) and QFracture.

What Are the Complications of Osteoporosis?

Osteoporosis is a condition that poses serious complications, especially in terms of bone fractures. Spinal fractures can occur without any external trauma, as the vertebrae can weaken to the point of collapsing. This can result in back pain, loss of height, and a hunched posture. Hip fractures are often caused by falls and can lead to disability and a high mortality risk within the first year following the injury.

Fractures caused by osteoporosis can be highly painful and require significant healing time, often leading to other complications. For instance, hip fracture treatment may involve extended bed rest, which elevates the risk of blood clots, pneumonia, and other infections.

Recovery from a broken hip can be lengthy, resulting in ongoing pain. Some individuals may lose their ability to live independently due to such a break.

What Are the Treatments for Osteoporosis?

Treating osteoporosis involves slowing or halting bone loss to prevent fractures and, in some cases, even reversing the condition.

There are several ways to treat osteoporosis, which can be combined.

1. Lifestyle Changes

Adopting a healthy lifestyle can significantly improve bone health and slow bone loss. These healthy lifestyle choices can be used to both help prevent osteoporosis and treat it.

Balanced Diet Rich in Calcium and Vitamin D

As a significant component of bone tissue, calcium is a crucial mineral providing strength and structure to your bones. Foods rich in calcium include:Milk.

Dairy products (e.g., yogurt and cheese).

Oily fish (e.g., salmon and sardines).

Certain green vegetables (e.g., broccoli and kale).

Calcium-enriched fruit juices.

Vitamin D is necessary for the body to absorb calcium efficiently from the diet. You can increase your vitamin D intake by getting enough safe sun exposure or consuming vitamin D-rich foods, such as:Fatty fish (e.g., salmon and mackerel).

Vitamin D-fortified milk.

Fish liver oils.

Eggs.

If you don’t obtain enough calcium or vitamin D from your diet, your doctor may suggest supplements. Make sure you use the ones your doctor recommends, as supplements are not as regulated as prescription drugs.

Appropriate Exercise Regimen

Physical activity is absolutely vital for bone health. Bone-strengthening activities include regular weight-bearing exercises like walking, dancing, tennis, tai chi, stair climbing, and strengthening and resistance exercises using free weights and weight machines.

Your doctor may even design a specialized exercise program for you.

Avoid activities that may cause bone fractures and prevent falls when exercising.

2. Medication

When osteoporosis is severe enough that diet alone cannot stop bone loss, your doctor will most likely recommend certain medications.

Bisphosphonates

Bisphosphonates are anti-resorptive drugs that prevent bone loss by inhibiting the body’s reabsorption of bone tissue. They are taken as pills or by an IV infusion, with different dosing schedules (e.g., monthly, daily, weekly, and yearly). These medications are also beneficial for reducing bone pain from bone metastases or multiple myeloma, lowering high blood calcium levels, and strengthening bones.

After taking bisphosphonates for five years, some individuals may still experience benefits even after stopping the medication.

Common side effects of bisphosphonates include flu-like symptoms, nausea, and mild kidney function impairment. However, there are rare but potentially severe side effects, such as jaw bone damage.

Different types of bisphosphonates include:Alendronate.

Ibandronate.

Risedronate.

Zoledronic acid.

Pamidronate.

Clodronate.

Denosumab

Denosumab is a biologic drug administered through an injection every six months. It is often used when other treatments have been unsuccessful. It shows promise in reducing bone loss more effectively than bisphosphonates in postmenopausal women.

As a receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappa B ligand (RANKL) inhibitor, denosumab blocks a protein involved in bone resorption, reducing the risk of fractures. However, its long-term effects are not fully known, and there are many side effects, including:Skin rash.

Eczema.

Fatigue.

Headache.

Peripheral edema.

Back pain.

Nausea.

Anemia.

Diarrhea.

Romosozumab

Romosozumab is an anabolic agent that helps build bone in individuals with osteoporosis. It was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat postmenopausal women with high fracture risk. It works by promoting new bone formation and reducing bone breakdown. The treatment involves two injections, given consecutively in the same sitting, once per month for up to one year.

However, it is important to note that romosozumab has a black box warning due to the potential slightly increased risk of heart attacks or strokes. As a result, it is not recommended for individuals with a history of either condition.

3. Hormone-Related Therapies

The following hormone-related therapies may treat osteoporosis:

Menopause hormone therapy: As low estrogen levels primarily cause postmenopausal osteoporosis, menopause hormone therapy (aka hormone replacement therapy or HRT) is often considered the primary option for preventing and treating osteoporosis, and its effectiveness has been supported by research. At the same time, it can relieve menopause symptoms. The female sex hormones used in this therapy are estrogen and progesterone. It is generally recommended for women under 60 and/or within 10 years of menopause. Possible side effects of this therapy include breast cancer, coronary heart disease, strokes, and blood clots.

Testosterone: This hormone may be prescribed for men with low bone density due to low testosterone levels.

Raloxifene: Raloxifene is a selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) that has the same effect on bones as estrogen. It is often given to postmenopausal women to increase their bone density, thus preventing spine fractures.

Calcitonin salmon: Also known as calcitonin, calcitonin salmon is a SERM used to treat postmenopausal osteoporosis. It works by inhibiting cells that break down bone tissue. By doing so, it reduces bone resorption, thus improving bone density. Calcitonin is used to treat women at least five years past menopause. Its common side effects may include facial flushing, an upset stomach, and skin rash.

Parathyroid hormone: The parathyroid hormone controls calcium levels in bones. Medications like teriparatide, which has a similar structure and function to parathyroid hormone, increase bone density and prevent fractures by stimulating bone-building cells. Teriparatide is prescribed for severe osteoporosis or when other treatments are not suitable. However, caution is advised for individuals who have undergone radiation therapy.

How Does Mindset Affect Osteoporosis?

Adopting a positive mindset can contribute to managing or lowering osteoporosis-related risks.

Although osteoporosis is a physical condition, mindset plays a role in its development. This is because our mental outlook and beliefs play a crucial role in how we respond to stressors, thus shaping our coping strategies and reactions, and psychological stress is a significant risk factor for osteoporosis.

According to one Taiwanese study, individuals diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) showed an elevated probability of developing osteoporosis compared to people without PTSD. Moreover, PTSD patients were more likely to develop osteoporosis at a younger age than those without PTSD. Further research is needed to understand better the underlying mechanisms linking PTSD and osteoporosis, which can, in turn, help with treatment recommendations.

In addition, depression is also a risk factor for osteoporosis. For instance, a cross-sectional study discovered that Caucasian girls and young women who experienced both anorexia nervosa and depression exhibited lower BMD than peers who had only anorexia nervosa.

Certain lifestyle factors and the use of a particular class of antidepressants partly cause depressed individuals’ higher risk for osteoporosis. Specifically, depression patients are typically less active than non-depressed people, tend to drink more alcohol, and sleep less than healthy individuals—factors that can all contribute to decreased BMD. Additionally, using SSRIs has been associated with a potential decrease in bone density.

Therefore, modifying lifestyle can serve as alternative or additional therapy to simultaneously alleviate the impact of psychological stress and osteoporosis. A positive mentality is essential to make the right lifestyle choices and better cope with the challenges brought by osteoporosis.

What Are the Natural Approaches to Osteoporosis?

In addition to the methods already covered, other natural treatments for osteoporosis offer promising results.

1. Medicinal Herbs

These herbs come in capsules, dried powder, and tinctures. Several can be used as ingredients in cooking and tea making. Some can also be used to extract essential oils.

Red Sage

Red sage (Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge) has been used in traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) to cure bone-related diseases. Researchers have found 36 clinical trials using red sage in combination with other herbs to treat all types of osteoporosis. These trials showed that the treatment was highly effective, with over 80 percent success rate and few side effects. However, further study is needed due to small trial sizes and little numerical data.

Over 100 compounds isolated from red sage have shown promising properties that can help prevent bone loss and stimulate bone formation. They target various pathways involved in bone remodeling, such as activating bone-forming cells, modulating the production of bone-destroying cells, and inhibiting collagen degradation, which is crucial for maintaining bone strength. Sage is also rich in vitamin K, which is important for bone mineralization.

Red Clover

Over a 12-week Danish study, menopausal women who consumed red clover (Trifolium pratense) extract daily experienced positive effects on their bone health, as evidenced by improvements in BMD and T-score at the lumbar spine. Notably, there were no changes in blood pressure or inflammation markers, and no adverse side effects were observed during the trial.

Turmeric

Turmeric (Curcuma longa) of the ginger family promotes bone stability and enhances the expression of essential markers that regulate bone metabolism. Its active ingredient, curcumin, can improve bone density. In an Italian study, 57 individuals with low bone density experienced notable improvements after taking a curcumin supplement for six months.

Horsetail

Horsetail (Equisetum arvense) is a medicinal herb shown to increase bone density in animal trials. It is a promising treatment option for osteoporosis due to its abundant silica content, aiding in calcium absorption and utilization and collagen formation. Additionally, this plant contains beneficial compounds such as alkaloids and phytosterols, effectively helping to prevent bone loss associated with aging and estrogen deficiency.

Thyme

Thyme (Thymus vulgaris) is often used as a spice in cooking. In an Iranian study (pdf) involving 40 postmenopausal women, researchers investigated the impact of daily consumption of 1,000 milligrams of thyme for six months. After six months, they discovered that thyme supplementation improved bone mineral density better than a calcium and vitamin D3 supplement.

Black Cohosh

Black cohosh (Actaea racemosa) has long been used in Native American medicine. Due to its phytoestrogen content, it is currently used to alleviate postmenopausal symptoms in the United States. Therefore, it is postulated that it can also be used to treat postmenopausal osteoporosis.

In one study, black cohosh extract produced a similar effect to raloxifene in treating osteoporosis in lab rats. Research has also shown that its active components can help prevent the activity of specific cells that can lead to bone loss.

Before using any herbs to treat osteoporosis, it’s essential to consult your doctor first, as supplements can have side effects and may interact with medications you are already taking.

2. Essential Oils

The essential oils extracted from certain herbs may also help boost bone health. Their consumption and direct application to affected areas may potentially enhance bone density. For instance, when added to the rats’ food, sage, rosemary, and thyme essential oils have been found to inhibit bone resorption in lab rats. The presence of monoterpenes such as borneol, thymol, and camphor in these oils directly contributes to the inhibition of bone resorption in rats.

3. Soybeans

Soybeans contain soy isoflavones, estrogen-like phytoestrogens, which have a structure similar to the hormone estrogen. When consumed, soy isoflavones interact with estrogen receptors in the body, leading to estrogen-like effects. Therefore, they can be used to treat postmenopausal osteoporosis.

Specifically, soy isoflavones can help reduce bone loss caused by menopause by decreasing bone resorption and promoting bone formation. Due to a relative lack of research in the area, well-designed human clinical trials are needed to assess the effects of soy isoflavones on osteoporosis.

4. Strontium

The mineral strontium has shown robust potential in treating and preventing osteoporosis. In a study involving postmenopausal women with osteoporosis, two groups were given either 2 grams of nonradioactive strontium ranelate daily or a placebo. The strontium group experienced a remarkable 41 percent reduction in the relative risk of developing new vertebral fractures.

5. Boron

Boron is another mineral that has a strong influence on bone metabolism. This is partly due to its effect on the absorption of vitamin D, calcium, and magnesium, along with its effect on optimizing sex hormones. Three milligrams per day has been suggested as an adequate dose.

6. Yoga and Tai Chi

A 12-minute daily yoga routine was shown to reverse osteoporotic bone loss in 227 patients. The study revealed improved BMD in participants’ spines, hips, and femurs. Furthermore, no side effects were observed during the study.

As a weight-bearing exercise, the ancient Chinese practice of tai chi can stimulate bone growth and potentially slow the rate of bone loss. According to a meta-analysis, participants who underwent tai chi training for over six months experienced significantly greater improvements in bone density of the lumbar spine, femoral neck, and trochanter compared to those who did not receive any intervention. Researchers concluded that tai chi might be a safe exercise for improving bone density loss. In addition, it helps improve balance, thus helping prevent falls.

7. Acupuncture

Acupuncture is widely used to treat osteoporosis in various countries, especially China. Animal studies have shown that acupuncture can strengthen bones by improving bone mass, mineral density, and structure. Clinical research has also indicated that acupuncture is more effective than a certain calcium and vitamin D supplement in enhancing BMD in postmenopausal osteoporosis patients.

How Can I Prevent Osteoporosis?

Preventing osteoporosis is crucial, as there are currently no safe and effective ways to restore bone health and structure once lost. Most of the aforementioned healthy lifestyle choices that can be used to treat osteoporosis can also prevent it. Additionally, you should:Get enough calcium and vitamin D: An adult’s recommended daily calcium intake is 1,000 to 1,200 milligrams, whereas the recommended amount for vitamin D is 600 to 800 international units (IU). Obtaining the necessary amount from your diet is always better than supplements. You should also consume enough potassium for proper calcium metabolism. The recommended daily intake for adults aged 19 to 50 is 3,400 milligrams for men and 2,600 milligrams for women.

Do the right exercises: This is vital to good bone health. To enhance musculoskeletal strength, perform a combination of balance and high- or low-impact weight-bearing and muscle-strengthening exercises.

Don’t smoke: Smoking should be avoided.

Limit alcohol: Alcohol consumption should be minimal.

Adolescents and Young Adults

Sufficient calcium intake during adolescents’ and young adults’ growth and maturation stages is crucial, as this period determines adult bone mass.

Furthermore, it’s essential to be aware of risks in young people, including conditions such as anorexia, bulimia, excessive athleticism, and some pituitary tumors, which can lead to estrogen deficiency and decreased bone density.

Perimenopausal and Postmenopausal Females

A perimenopausal female is a woman transitioning into menopause. During menopause, assessing each patient’s osteoporosis risk factors is crucial as part of their medical history. By identifying these factors, doctors can modify their patients’ behavior to reduce menopause’s impact on bone health. Simply increasing calcium intake may not be enough to counteract the accelerated bone loss during these periods. Estrogen therapy can be an effective treatment option in such cases.

Regular, moderate exercise combined with a well-balanced diet rich in calcium and vitamin D can help slow the rate of bone loss. Taking a comprehensive approach to ensure optimal bone health during this critical period is essential.

No comments:

Post a Comment