This is a great list and i do suggest that you make that effort to have read all of them, sooner or later. Personally i have read them all throughout my life and most often as a teenager. To have lived and not read is unimaginable. It is too like living a life in which most is left on the cutting floor. What are you thinking? There is no faster way to absorb an unique expereince without actually living it.

Watching it dulls soon enough when you can engage your mind to produce a living world through a book.

The techno revolution has mostly sorted itself out and it has become time to step back and redevelop our reading skills in support of contemplative meditation..

A detail from “Reading Woman” (portrait of artist's wife), after 1866, by Ivan Kramskoy. (Public Domain)

Great Books I Wouldn’t Want to Be In (And Some I Would!)

March 31, 2019

Updated: April 4, 2019

If there’s something book lovers like almost as much as

reading books, it’s talking about books. About the plot details. About

the characters. About the meaning. We feel for and with the

characters. We immerse ourselves in the details. We virtually put

ourselves into the stories.

Just for fun, I thought I would imagine what it would be like to be a character in the works of a selection by well-known authors. I imagined

myself being an inhabitant in the world and story the author created,

not always the protagonist, and not necessarily as myself. It turns out,

I would not like to be in many of them as much as I enjoyed reading them.

What follows is my rating of each. The authors are listed chronologically by the dates of their birth.

👎 Just kill me first.

There are many unpleasant ways to die in “The Iliad” or “The

Odyssey.” I would consider myself lucky if I were killed off in the

Trojan War in “The Iliad” rather than head home victorious, say no to

drugs, resist the temptation of the siren song, avoid becoming a Cyclops

snack, skirt a whirlpool while at the same time not being swallowed by

the six-headed Scylla, to ultimately be drowned in a sea storm as

punishment for eating a steak. Call me weak.

👍 Count me in!

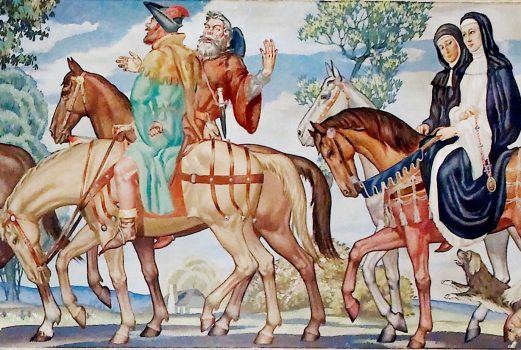

Basically, in “The Canterbury Tales,” I get to go on a long

pilgrimage on foot, to the shrine of Thomas à Becket, with a passel of

mix-and-match mates, telling and listening to entertaining tales along

the way. Accommodation in inns is assured, and the whole thing is

entirely voluntary. What’s not to like?

William Shakespeare (1564–1616, English)

👍👎 To be, or not to be in his works?

I’ll go with his comedies, but pass on his tragedies. Who would

wholly opt out of the chance to speak the brilliant dialogue penned by

The Bard, maneuvering in and out of hilarious plans within plans? The

beauty of it is, anyone with a penchant for the stage can be in them! Shakespeare wrote plays!

Jane Austen (1775–1817, English)

👍 My good opinion of the prospect has been easily gained.

On the liability side, I would almost certainly be a poor young woman

with little prospect of a good marriage. But on the asset side, by

Austen’s reckoning, “poor” means that I can afford only one servant. Balls

and walks in the English countryside are guaranteed. Best of all, my

witty personality will result in my becoming the wife of a man in

possession of a good fortune (and handsome, in the bargain).

Charles Dickens (1812–1870, English)

👎 Low expectations for this one.

What I don’t understand is where the expression “A Dickens

Christmas” came from. Haven’t those who use the phrase read any of

his masterful books? A true Dickens Christmas is sure to be populated

with selfish, gruesome, underhanded, and unlikable figures if it were

anything like his books. I would definitely not like to enter a world

like that.

Charlotte, Emily, and Anne Brontë (1816–1855, 1818–1848, 1820–1849, English)

👎 I would always rather be happy than be in their books.

These gals can write! But they can write me out of

their novels. Gothic romance and melodrama is not for everyone. The

damp English weather may not have been conducive to good health and

cheerfulness for these young ladies, but it did wonders for their

creative imagination. As a potential character in their books, I opt for

less of the moors.

👎 Nyet.

For space considerations, I’m lumping together these two Russian

literary geniuses. Remembering the names and nicknames of hundreds of

people and the faces they go with is not my forte. And I like to be

happy. While I might learn great moral lessons, if I had to be in one of

their books, I just might throw myself in front of a train.

Jules Verne (1828–1905, French)

👍 I’m sure to go far in his books.

Adventure

on the cutting edge of future Steampunk technology with plenty of

financial resources—and a servant—actually appeals to me. It would be

like a science field trip to plunge the depths in Captain Nemo’s

Nautilus, or explore the depths of the Earth. Or a speed vacation,

circumnavigating the globe in 80 days. I’d go a long way for inclusion

in Verne’s novels. Perhaps even 20,000 leagues.

Mark Twain (1835–1910, American)

👍 Any friend of Twain’s is a friend of mine.

Not unlike the celebrated frog of Calaveras County, I’d jump at the

chance to be in any of Mark Twain’s books. (Though, I’d better be sure

no one filled me with a handful of shot first.) Fun, adventure, and more

than a handful of sharp American wit fill his pages.

Oscar Wilde (1854–1900, English)

👍 I would earnestly enjoy being in some of his works.

Delightfully

convoluted first-world problems, those lovely late Victorian fashions,

and happy endings! Sounds like an ideal marriage to me! But please, I’d

rather not be in “The Picture of Dorian Gray.”

Kenneth Graham (1859–1932, English)

👍 Believe me, there would be nothing half so much worth doing as messing about in this book!

Although “Wind in the Willows” is a talking-animal book, it ought to

be in every well-read adult’s library. Friendship is the main thing

here. There is plenty of lolling about in boats, picnicking, and

visiting neighbors. The main turmoil comes from Mr. Toad’s wild streak,

which necessitates continual rescue by his faithful friends. Graham’s

idyllic English countryside is one I would inhabit with enthusiasm!

👍 I have the courage for this.

I’d have to be raised by wolves to not want to be in his books. Oh, wait. I’d probably enjoy it even more if I were raised

by wolves, like Mowgli in “The Jungle Book”! Excitement, rites of

passage, and becoming a grown-up are the advantages Kipling’s characters

enjoy in his jungle and sea adventures.

Jack London (1876–1916, American)

👎 I don’t hear the call of his books.

I admit, the foremost reason I do not wish to be in London’s books

stems from my aversion to being cold. I could not bear to be cast in a

scene in which the temperature is 50 degrees below zero. And you just

can’t trust this author to let your hands work well enough to strike a

match to start a fire. I’m not going there.

P.G. Wodehouse (1881–1975, English)

👍 What ho! I’ll go!

I would generally get to hobnob with the upper classes of the

unrealistically idyllic 1930s England. His characters are endearing, and

the hilarious predicaments he creates are thoroughly G-Rated. Yet, his

stories are peppered with references enjoyed by the well-read and highly

educated. I would let Wodehouse write me into anything!

J.R.R. Tolkien (1892–1973, English)

👎 They can go without me.

I once went on a 22-mile hike over two days. That was enough for this

not overly outdoorsy girl. These people (and hobbits, and dwarfs, and

elves, and whatever else) were on their arduous, dangerous, Middle-earth

saving journey for over six months—one way!

C.S. Lewis (1898–1963, English)

👍 Did someone say wardrobe?

I’m not up for inclusion in his space trilogy, but I’d be willing to

go to Narnia. Finding a secret passage to a mysterious, magical world

filled with potential danger wouldn’t be so bad, under the providential

protection of a good, albeit not tame, lion. Who wouldn’t want to

encounter centaurs, winged horses, and all manner of mythical

characters?

George Orwell (1903–1950, English)

👎 I vote No.

Orwell is mostly known for dystopian political commentary. Dystopia

is not my ideal place to hang my hat. Mostly, his books make you glad

you don’t live there, and that’s the point. Despite my

reluctance to be in them, I do want to put in a good word for one of his

more humorous and delightful novels, “Keep the Aspidistra Flying.” I

still don’t want to be in it, but I assure you, it has an uplifting,

buoyant ending.

Evelyn Waugh (1903–1966, English)

👎 A vile idea.

Waugh may be a great writer, but even in his masterful novel

“Brideshead Revisited,” one finds no character truly lovable. I get the

feeling that even Waugh didn’t like them. Who knows what he might do

with me in one of his books!

Flannery O’Connor (1925–1964, American)

👎 Ahhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhh!

Weird. Southern Gothic. Grotesque. Be sure to read them all!

Why Live It If You Can Read About It?

It is interesting that at least half the great books I considered were stories I would not want to enter, but loved reading.

Literature allows us to gain a breadth of experience that our own

circumstances would not permit and at very little expense to us. A good

writer can show us the world. He or she can take us into battle,

demand rigorous moral discrimination, and allow us to grapple with evil,

unharmed. We then step back into our mundane lives better people than

we were before.

For this, I am truly grateful to the gifted authors of the past.

Susannah Pearce has a master’s degree in theology and writes from her home in South Carolina.

No comments:

Post a Comment