Interesting report here. What is really interesting is that it comes out now. Why is JFK jr getting well crafted press coverage just last Christmas and now?

Then we have the outstanding MEME regarding the possibility that he will leave witness protection after twenty years this July in preparation for stepping in as the Vice Presidential candidate with Trump. Again Pence's loyalty has lately been called into question. This may or may not be valid, but we are certainly filling the news machine with critical background.

The next two months will see serious public arrests. I do not want to speculate on the extent. I do think that a large number of secret arrests have also taken place that will be told long after the fact. Why wait for nobodies?

Thus following with JFK jr becomes timely.

A 2020 TRUMP JFK jr ticket is a nice fantasy. To date I have been unable to prove it impossible or even implausible. Recall again that there is a deeply developed plan at work with Mil Intel and we have seen ample verification through Q. The best verification though is that many obvious decisions have been in terms of personnel that were carefully timed and as carefully presaged. There is ample indication of the application of deliberate placeholders to cover for background activity.

The Inside Story of John F. Kennedy Jr.'s George Magazine

In the '90s, John F. Kennedy Jr. founded and edited a revolutionary magazine called George, which covered politics like it was pop culture. Was it folly—or a glimpse of the Trumpian future?

BY KATE STOREYAPR 22, 2019

Getty Images

John F. Kennedy Jr. stared out his window overlooking the Hudson River, past the piles of proofs, magazines, Knicks ticket stubs, and take-out containers on his desk. He cracked the faintest smile, as one colleague remembers. It was the summer of 1996; he was the editor of a magazine named George, which was less than a year old and still finding its way; and an idea for the September cover had just occurred to him: Madonna dressed as his mother, Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis.

He asked his assistant, RoseMarie Terenzio, for a notepad so that he could dash off a note to Madonna with the request, while Matt Berman, George's creative director, sketched what they hoped would become the cover. Shot by avant-garde fashion photographer Nick Knight, the image would be disguised in such a way that, upon first glance, the reader would think the subject was indeed the editor’s mother, before taking a closer look to realize it was Madonna. Making the cover even more provocative was the fact that Kennedy was rumored to have dated Madonna before starting the magazine.

Unfortunately, the pop star—perhaps one of the few people more famous than Kennedy at that time—shot him down. "Dear Johnny Boy," she began in her handwritten fax (which appears in Terenzio’s book, Fairy Tale Interrupted), "Thanks for asking me to be your mother but I’m afraid I could never do her justice. My eyebrows aren’t thick enough, for one."

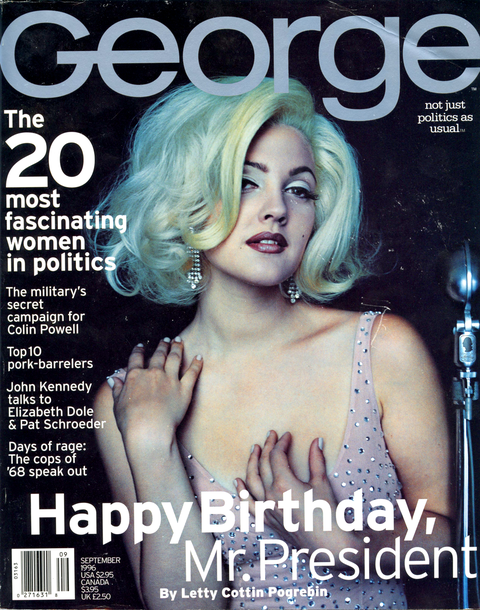

With Madonna out, the September cover took a decidedly different turn—instead of referencing his mom, Kennedy chose to nod at another well-known woman in his dad’s life: Marilyn Monroe.

Drew Barrymore was posed in a nude-colored cocktail dress and platinum wig, with a mole perfectly placed on her left cheek. The idea came from George’s executive editor, Elizabeth Mitchell, who suggested it as a fiftieth-birthday tribute to President Bill Clinton. The reference: In May 1962, in front of fifteen thousand people during a Democratic-party fundraiser at Madison Square Garden, Monroe had famously serenaded Kennedy’s father ten days before his forty-fifth birthday with a breathy, seductive "Happy Birthday, Mr. President." The subtext to the song, of course, is that the president and the actress were rumored to have had an affair.

That photograph might seem a strange choice for a man who adored his mother—even stranger than asking Madonna to impersonate her—but the thing was, according to Mitchell, Kennedy never believed anything had happened between his dad and Monroe. "He just thought it was sort of tweaking the expectations of the public," she says all these years later.

Drew Barrymore appeared as Marilyn Monroe for the September 1996 issue.

Hearst Magazine Media, Inc.

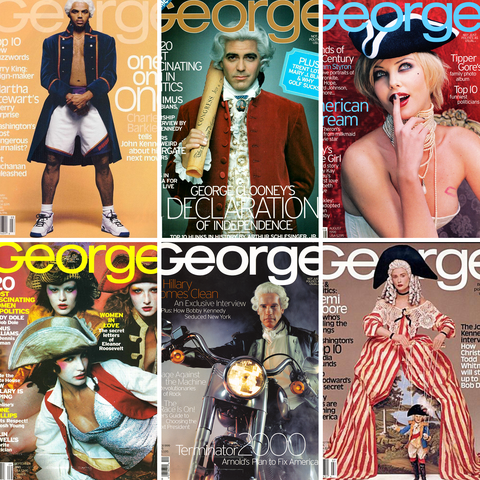

An irreverent play on politics and pop culture with a dash of Kennedy intrigue, the Barrymore/Monroe cover accurately sums up George, the magazine Kennedy launched in September 1995. His concept, in today’s terms at least, seems relatively straightforward: "a lifestyle magazine with politics at its core." Back then, however, George was revolutionary; there had never been anything quite like it. Nor had there ever been a magazine editor quite like John F. Kennedy Jr., a lawyer by training. Perhaps predictably, media critics sneered, lampooning him as aimless and unqualified, his idea frivolous. Esquire called the magazine "the riskiest venture of a pampered life indelibly marked by tragedy." Newsweek: "Kennedy has been able to live without real responsibility, as a bit of a slob, considerate to his (many) women, not quite sure what he wants to do, looking forward to . . . the Frisbee game in the park. . . . Now, apparently, he’s ready to grow up." The Los Angeles Times asked: "Is John Kennedy Jr.’s George making American politics sexy? Or is the magazine just dumbing it down more?"

But Kennedy’s instincts were right: In the twenty years since his death, politics and pop culture have become so intertwined that candidates now spend nearly as much time courting voters on late-night shows as they do on the Sunday talk circuit. Politicians are covered as if they were celebrities, while celebrities seek out a voice on politics. The current president is largely a product of reality television, and his predecessor recently signed a production deal with Netflix. Oprah Winfrey has been seriously touted as a potential presidential candidate, as have—somewhat less seriously—The Rock and Mark Cuban. As the son of the thirty-fifth president and an elegant First Lady–turned–book editor, Kennedy was uniquely positioned to both cover and promote the marriage of politics and pop culture—because he lived it.

Some of art director Matt Berman’s sketches which eventually became George’s covers.

Some of the people close to him whom I spoke with believe George was Kennedy’s first step toward his own eventual run for office. His plan, they say, was to build it up as a successful magazine that could survive without his star power so that he could one day step into politics. But he ran out of time. On July 16, 1999, less than four years after the first issue, the aircraft Kennedy was flying plunged into the Atlantic Ocean, killing him; his wife, Carolyn Bessette; and her sister Lauren Bessette. Just eighteen months later, Georgefolded.

Beyond the personal tragedy was a professional one: Kennedy had worked hard to build a fiercely loyal team; an exciting, buzzy brand; and a new way to think about politics. But the personal and professional were hard to separate. It was the Kennedy name that persuaded publishers, advertisers, and readers to take a chance on him, but at the same time, it was his family’s legacy that complicated his role as an editor and led to conflicts both inside and outside the magazine.

“John died before his time,” says Frank Lalli, the editor who replaced Kennedy (and who controversially put Donald Trump on the cover in 2000). “And this magazine died before its time.”

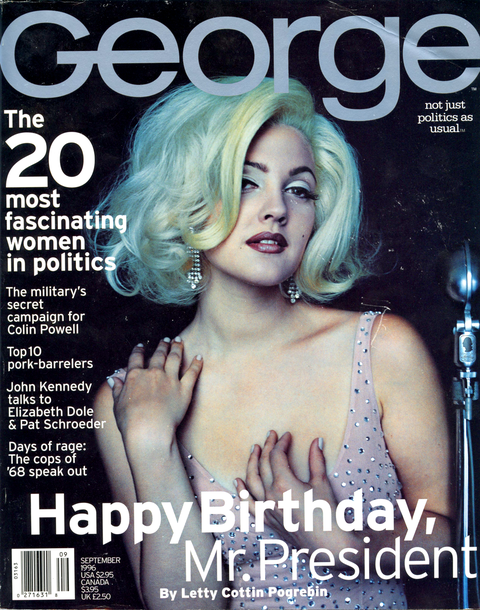

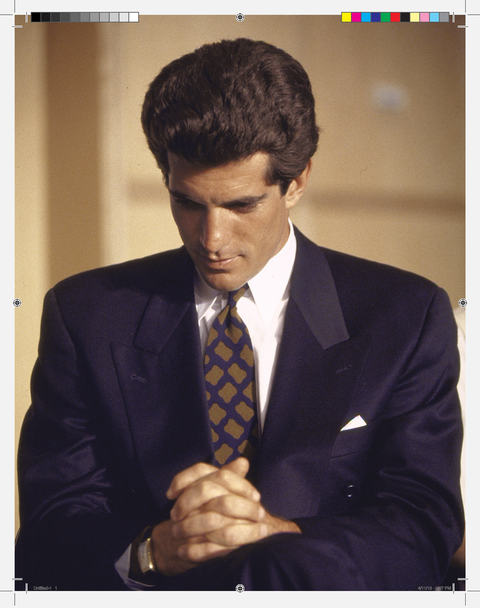

After Kennedy graduted from NYU School of Law in 1989, he worked worked as an assistant district attorney.

Getty Images

After graduating from Brown University, in 1983, and New York University School of Law, in 1989, President John F. Kennedy’s second child worked as an assistant district attorney in Manhattan from 1989 to 1993. It was President Clinton’s successful 1992 campaign, including his saxophone performance on The Arsenio Hall Show, that inspired Kennedy to create a political magazine focused more on personalities than on policy.

He brought up the idea over dinner with his friend Michael Berman, who was running the Manhattan public-relations firm PR/NY. Berman was on board. Their first step was attending a two-day seminar in 1993 called “Starting Your Own Magazine,” hosted at a New York Hilton. During one of the sessions, an instructor told the class, “You can successfully launch a magazine in just about anything except for religion and politics.” But Kennedy already had his mind made up.

Keith Kelly, then a reporter for Folio magazine and now a media columnist at the New York Post, got wind of the famous attendee at the conference. When Kelly arrived, he saw someone who looked like Kennedy standing at the front of the class helping the instructor fix a projector. That can’t be John-John, he thought. But when he approached the man later in the day, he realized it was indeed him.

Media reporter Keith Kelly spotted Kennedy at a two-day seminar in 1993 called “Starting Your Own Magazine.”

Getty Images

“Hey, John, are you going to start your own magazine?” Kelly asked.

Kennedy demurred. “Oh, I don’t know. I don’t know.”

Kelly pressed: “If you ever do, could you let me know first?”

Kennedy and Berman continued working on the project sporadically into spring 1994, when Kennedy set up a secret shop in Berman’s office, coming in every day to strategize. After a few months, Berman announced to his team he was selling his firm and going into business with Kennedy. The two men brought on Berman’s former employee RoseMarie Terenzio as their assistant, and they got to work on the new project.

“They thought it was too political, too hot of a potato to handle.”

The early nineties were a golden age for glossy magazines. It was an incredibly lucrative business, because, in the days before the Internet became ubiquitous, companies poured their advertising budgets into magazines. Readership was surging, particularly among celebrity-focused titles like People, which drew 3.1 million readers a week in 1994. The biggest magazines helped define the zeitgeist with their covers, turning celebrities into overnight icons—a nude and pregnant Demi Moore photographed by Annie Leibovitz for Vanity Fair, or Rolling Stone crowning Nirvana the “New Faces of Rock” in 1992. But finding a company willing to back Kennedy and Berman’s concept was difficult—in spite of Kennedy’s famous name—because of the belief that it was difficult to sell advertising in political publications. Compared with glossy magazines, titles like The New Republic and the National Review had smaller circulations and fewer ads, and the ads they did have were typically from the low-ticket likes of university presses.

Kennedy had pitched a George prototype to publishing giant Hearst, the owner of magazines including Cosmopolitan and, yes, Esquire, but the company declined to work with him, according to Samir Husni, who consulted for Hearst in the mid-nineties. “They thought it was too political, too hot of a potato to handle,” he says. “They didn’t see a business model that would sustain the magazine.”

When Rolling Stone cofounder and Kennedy family friend Jann Wenner heard about the magazine, he was irate, according to a 1995 Esquire story. “What’s this about?” he allegedly asked Kennedy. “You better see me immediately. Politics doesn’t sell. It’s not commercial.”

In early 1994, Berman and Kennedy found a partner in David Pecker, then president of Hachette Filipacchi Magazines, which at the time published Elle, Car and Driver, andWoman’s Day. (All three are now Hearst titles. Pecker, meanwhile, has become famous for his friendship with Donald Trump; Pecker’s current company, American Media Inc., which published the National Enquirer,helped squelch negative stories in 2016 about then candidate Trump.) Pecker jumped at the opportunity to make a deal with Kennedy and, according to reports from that time, agreed to invest $20 million over five years. In a 1995 interview with New York magazine, Pecker accidentally called George a “living, breathing orgasm,” which, the writer posits, “doesn’t, in fact, seem too far from his hopes for it. All in all, Mr. Pecker is pretty excited.”

ADVERTISEMENT - CONTINUE READING BELOW

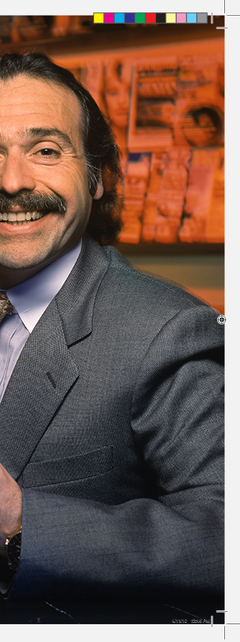

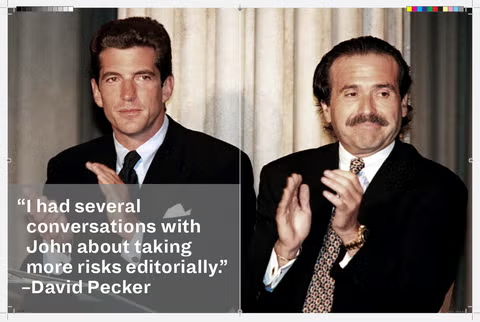

David Pecker ran Hachette Filipacchi Magazines in 1994 when the company took on George.

Getty Images

“John had shopped the idea for George to all the major publishers, many of whom, like Jann Wenner, were personal friends. One by one they turned him down, usually with the excuse that a magazine connecting politics and pop culture would never work,” Pecker recalls via email. “Eventually, John came to see me at Hachette and when he explained his concept, I enthusiastically agreed to go forward. I not only recognized the reader appeal a magazine edited by John would have, but all the advertiser interest it would generate as well.”

One of the first things Hachette wanted to change was the magazine’s name—the company offered alternatives like Crisscross, meant to suggest the intersection of politics and pop culture. But Kennedy and Berman insisted on George—a mildly irreverent nod to the first president—and when an anonymous source leaked to Page Six that Kennedy was starting a magazine called George, the name was set.

Pecker was right about the advertisers. Before the magazine launched, Kennedy went to Detroit to lure the auto companies—traditionally among the most desired of advertisers, both for their deep pockets and for their blue-chip cachet—into buying space.

“I went to Detroit to talk to people at General Motors, Chrysler, and Ford. I followed John by a week,” former Vanity Fair editor Graydon Carter remembers. “People were lining up around corners to get to see him. He was filling auditoriums. By the time I got up there, it would be just me and my salesperson out there in a small office of metal furniture. We were very much overshadowed by the presence of John Kennedy.”

Kennedy’s salesmanship worked, with GM becoming George’s largest advertiser. Pecker says, “The first issue sold out with over five hundred ad pages, more than the September issue of Vogue at that time.”

In early 1995, Kennedy was quietly building his staff with the help of a discreet headhunting firm that had worked with his uncle, Senator Robert F. Kennedy. One of the people brought in was Elizabeth Mitchell, an editor at Spin (another magazine started by a famous scion: Bob Guccione Jr.), who would eventually become George’s executive editor. Kennedy struck Mitchell as curious, funny, and down-to-earth.

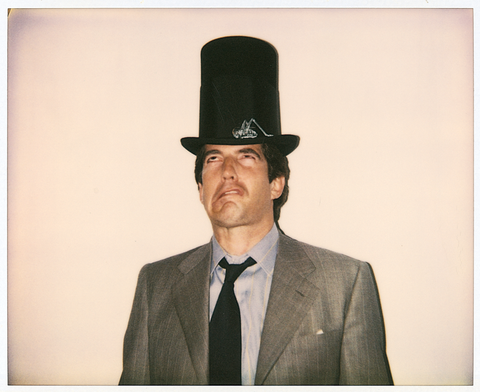

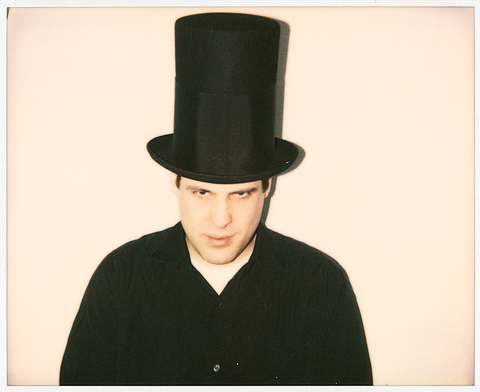

Kennedy goofs around with an Abraham Lincoln-inspired top hat at the George offices in a photo

taken by his creative director Matt Berman. Kennedy's former colleagues describe him as funny and down to earth.

Courtesy of Matt Berman

"He had definitely read through a lot of the pieces I had edited at Spin,” Mitchell says. “I was in charge of the international investigative features and the heavier political content, and he had specific questions about the things I worked on. Mainly he was interested in how we got access that allowed us to embed reporters in the Irish Republican Army, in a helicopter in Mogadishu, into the offices of the key generals during the Yugoslavian war. And how had I found the writers."

At one point during the meeting, Mitchell recalls, a staff member from the headhunting firm asked what they wanted to drink. Kennedy wanted water, to which the staffer responded: “Do you want Evian ice cubes or tap ice cubes?” Kennedy, to his credit, considered it an odd request. “You know, a block of ice cubes are fine,” he said. “It doesn’t have to be fancy.”

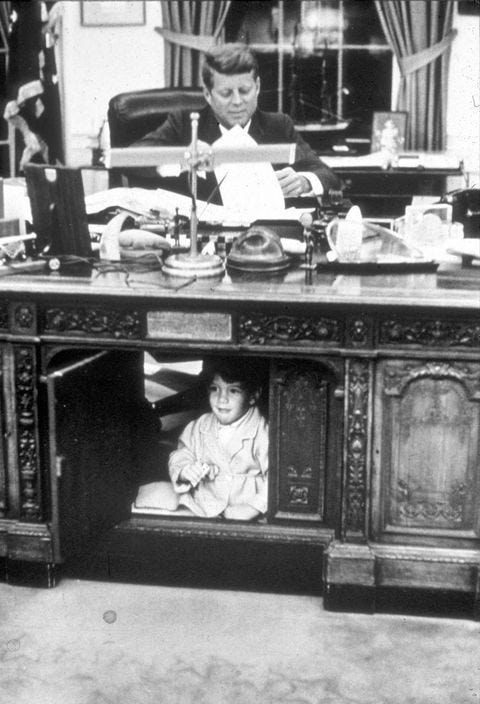

Kennedy was born two and a half weeks after his father was elected the 35th President of the United States.

Getty ImagesGetty Images

The initial staff was composed of just eight editors, who shared office space on the forty-first floor of Hachette headquarters on Broadway and Fifty-first Street with the staffs of Elle and another fashion magazine, Mirabella. George’s new colleagues would conveniently find excuses to use the photocopier right outside Kennedy’s office to catch a glimpse of the handsome, famous editor. A giant orange George logo adorned a hallway wall in the mostly drab space. Kennedy’s own office featured a black-and-white photo of Mick Jagger on the family’s boat in Hyannis alongside a bust of George Washington and a photo of Kennedy himself as a little boy on his dad’s shoulders. Kennedy’s girlfriend, Carolyn Bessette, sent over a mid-century sofa to dress up the space, but it quickly became covered by rumpled T-shirts and sweatpants.

“We went rollerblading with John in Central Park at midnight. And it was just the fucking coolest.”

Once in place, the team had just three months to create the premiere issue. They put in grueling hours, working forty days straight, taking one day off, then working another forty. They’d sometimes stay at the office past midnight—including Kennedy, fueled by coffee and Diet Coke. On weekends, dressed in shorts and a T-shirt, he would surprise the staff by sneaking his black-and-white puppy, Friday, into the office in a duffel bag. On late nights, the editors would order pizza or dinner from Rice ’n’ Beans, Kennedy’s favorite restaurant on Ninth Avenue.

“It was notable in this grinding work situation that you would look over and there’s John working away with you,” says Mitchell. “You felt like, okay, that person who could do anything in the world is choosing to be here doing this work; you can certainly suck it up and keep going.”

Kennedy knew how important his first cover would be to establish the publication not as the “John Kennedy magazine” but as something that stood on its own. To brainstorm cover subjects, he invited fashion photographer Herb Ritts, a friend of his, and Matt Berman, the creative director (and no relation to Michael Berman), to his TriBeCa loft. Over Rolling Rocks with Bessette, they threw out names of all-American celebrities who could represent the brand. Kennedy suggested Bill Clinton. Ritts proposed supermodel Cindy Crawford, who at the time was also appearing regularly on TV in Pepsi ads and as the host of MTV’s popular House of Style.

“Cindy Crawford’s perfect,” Bessette said. “She’s all-American, a self-made woman, sexy, strong, and smart.”

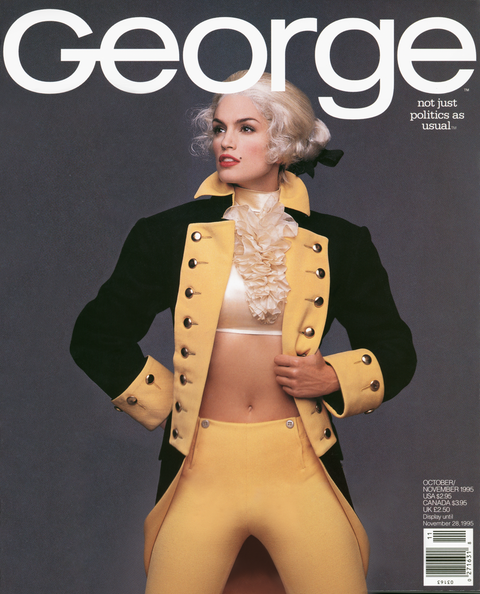

Ritts suggested dressing Crawford as George Washington—a cheeky play on politics and pop culture. They all agreed, and Kennedy called the model himself to ask her to be on his first cover.

“He called my hotel. He reached out directly. And who’s going to say no?” Crawford says. “I trusted Herb Ritts enough to know it would be okay. But it was kind of like, I’m going to do what? Dress like George Washington? With the wig and everything?”

Kennedy called model Cindy Crawford personally to ask her to appear on the cover of the first issue of George. “He called my hotel. He reached out directly. And who’s going to say no?” she tells Esquire.

Hearst Magazine Media, Inc.

It wasn’t just the wig. After studying old paintings on the set of the photo shoot, the team decided to stuff Crawford’s skintight breeches with a sock. Matt Berman was unsure whether Kennedy, who wasn’t on set, would be quite that adventurous, but he figured they could make changes in postproduction. Sure enough, when Kennedy saw proofs a few days later, his response to Berman was “Maestro, what the fuck?” They airbrushed out the bulge.

At this point, two years after that how-to-make-a-magazine seminar, Kennedy made good on his promise to Keith Kelly. He called the reporter and said he was granting him the first interview about George.

As Kennedy geared up for the launch, his personal life hit a milestone. During Fourth of July weekend in 1995, at his family’s home in Martha’s Vineyard, Kennedy proposed to Bessette, a striking, stylish blonde who worked in public relations for Calvin Klein. They hoped to keep the engagement quiet for as long as possible, as Bessette prioritized her privacy.

The famous image of Kennedy as a toddler saluting his father's casket during his funeral procession.

New York Daily News ArchiveGetty Images

Kennedy had served as America’s crown prince since his birth—only two and a half weeks after his father was elected president, in November 1960. John F. Kennedy would die just three days before his son’s third birthday, the toddler becoming an instantly tragic icon after photographers snapped him saluting his father’s casket. Kennedy’s mother shielded him and his sister, Caroline, from the press as they grew up in Manhattan. But as soon as he finished boarding school, the tabloids descended. After People named him its Sexiest Man Alive in 1988, his relationships with celebrities like Sarah Jessica Parker and Daryl Hannah were covered breathlessly. The news that he was now off the market would most certainly cause a media frenzy.

The New York Post broke the engagement story the Friday before Labor Day—mere days before Kennedy and Michael Berman’s scheduled press conference to unveil George. Berman was furious, worried the gossip would overshadow the launch, recalls Terenzio, who was asked to fax a statement denying the engagement to the Associated Press. Sure enough, there was a deluge of coverage about her statement. When hundreds of reporters and dozens of TV cameras showed up at Federal Hall—where George Washington took his presidential oath—on September 7, 1995, for the first George press conference, they may have been hoping for titillating details about Kennedy’s love life. But the event was focused squarely on the magazine.

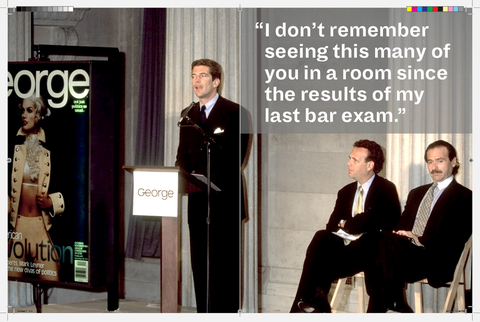

Kennedy, dressed in a navy double-breasted suit with a bright white pocket square, stepped behind the small wooden podium in the vast marble building. Berman and Pecker sat on small wooden folding chairs to his left, and to Kennedy’s right stood the first cover of George, on which Crawford posed confidently in a powdered wig and midriff-baring costume. It was Kennedy’s first time addressing reporters since his mother’s death the year before, and he’d worked with an image consultant who prepped him on personal or potentially embarrassing questions that might be asked. Still, he looked nervous.

Kennedy presents to reporters the first issue of George as his partner Michael Berman (center) and David Pecker look on.

Getty Images

“I don’t think I’ve seen as many of you in one place since they announced the results of my first bar exam,” joked Kennedy, who had appeared on the cover of the New York Post in 1990 with the headline “The Hunk Flunks” after failing the New York bar exam for a second time. He talked about the mission of his magazine, and when asked what his mother would think about his new venture, Kennedy said, “I think she’d be mildly amused, glad she wasn’t standing here, and very proud.”

With the tagline “Not just politics as usual,” George hit newsstands in September 1995, a bimonthly selling for $2.95. It was a runaway success, selling out its print run of nearly five hundred thousand issues—by comparison, The New Republic typically sold one hundred thousand issues at that time, while Vanity Fair had more than 1 million readers a month that year.

Kennedy and his cousin Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. prepare to go kayaking at the family's compound in Hyannis, Mass.

Getty Images

The political landscape was primed for George. The Clintons had brought youth and accessibility to the presidency for the first time in years. Secondary figures like George Stephanopoulos, then a thirty-four-year-old White House boy wonder, were getting increasing attention. And on Capitol Hill, Newt Gingrich, who in 1994 had led Republicans to their first House majority in forty years, was weaponizing the media like no other leader of Congress had before. George treated budding D. C. personalities like celebrities and brought movie stars into the political conversation. Early issues featured an essay titled “The Next American Revolution Is Now” by novelist Caleb Carr, an article about Time Warner’s war against rap music, a satirical piece about Jesus running in the ’96 election by Beavis and Butt-Head writers Sam Johnson and Chris Marcil, and a Q+A with Planned Parenthood strategist Leslie Sebastian.

Throughout the fall of 1995, the staff kept up its grueling hours and Kennedy remained a hands-on editor. The cover motif of celebs decked out in early-American regalia stuck, with Robert De Niro posing as a sword-carrying Washington for the second issue and Charles Barkley in a powdered wig and basketball shorts on the third cover. After the success of the first three issues, Hachette increased the magazine’s frequency to monthly and doubled the staff. At the same time, Kennedy’s second-in-command, Eric Etheridge, resigned. Etheridge has never spoken publicly about George and declined to be interviewed for this piece, but others at the magazine say he and Kennedy had disagreed about the direction of the magazine.

Hearst Magazine Media, Inc.

“I really respected Eric. I thought he was extremely smart. He had a really tough situation, which was mapping out the definition of what George is,” says Mitchell. “I think he probably had an idea that John was going to be less involved in the editorial decisions, but it was clear that John wanted to be involved.”

ADVERTISEMENT - CONTINUE READING BELOW

Mitchell was promoted to the role of Kennedy’s No. 2, but whereas Etheridge had simply been listed on the masthead as editor, Mitchell was given the title of executive editor, indicating that editor-in-chief Kennedy alone was the top editorial voice. In pitch meetings, he would pepper editors with questions about their angles. Though he didn’t have a formal journalism training, he had good instincts about what made an interesting story, according to his staff. His frequent question was “Why would people care about this?” Then senior editor Richard Bradley remembers filing a profile on presidential candidate Pat Buchanan to Kennedy, who remarked, “It feels like you’re missing the point on this.” Kennedy thought the story focused too much on policy and Washington intrigue and not enough on personal details, which he believed George’s readers were always more interested in.

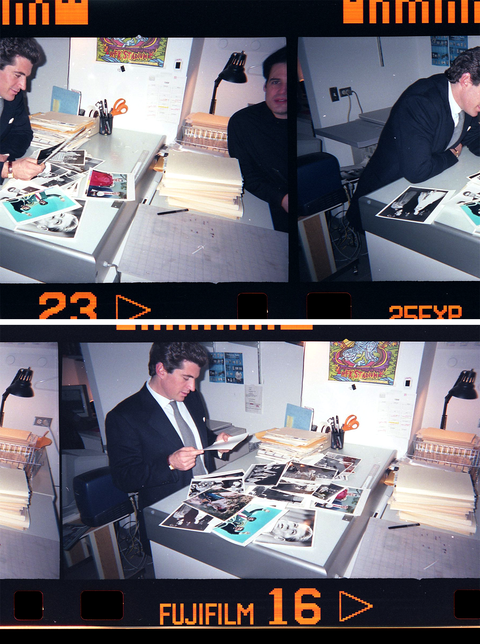

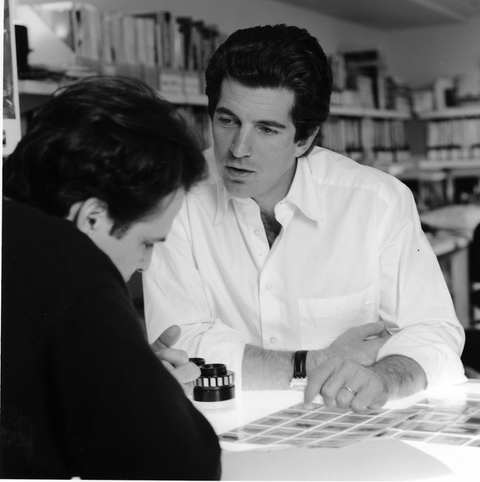

Kennedy and creative director Matt Berman look over photos in the George art department.

Courtesy of Matt Berman

“He was a dominant force in every meeting,” says senior editor Ned Martel. “Nothing went forward without him knowing about it, or understanding it completely.”

The staff was young—most were in their twenties—and Kennedy took his role as a leader seriously. He initiated team outings to movie matinees, plays, and baseball games and organized touch-football games—a Kennedy family tradition—in Central Park’s Sheep Meadow. The editorial team was tight-knit. Former staffers beam when sharing memories of Kennedy showing up on his bike at their birthday parties at downtown bars and going out of his way to give personal gifts for holidays.

“Even though he often did stay late, [Kennedy] also would just disappear, and one night we disappeared with him,” recalls associate editor Hugo Lindgren. “Me and my friend Manny—we were both associate editors—went Rollerblading with John in Central Park at midnight. And it was just the fucking coolest.”

Kennedy (pictured with Matt Berman) clocked long hours at George, sometimes staying past midnight to work on issues.

Courtesy of Matt Berman

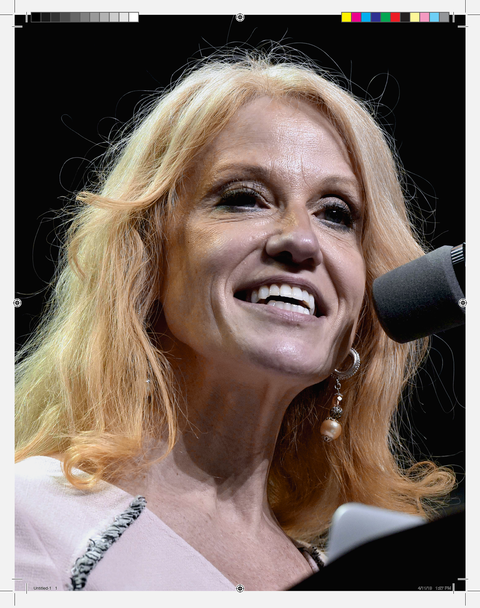

In each issue, Kennedy wrote an editor’s letter and interviewed a famous figure, such as former Alabama governor George Wallace, Elizabeth Dole, and Gerald Ford. Other standing features included a pop-culture-figure column called “If I Were President.” In the first issue, Madonna proclaimed, “Howard Stern would get kicked out of the country and Roman Polanski would be allowed back in.” There were interviews with up-and-coming political personalities—the young conservative pollster Kellyanne Fitzpatrick, now known by her married name, Kellyanne Conway, was interviewed about “why female and Generation X voters are ripe prospects for the GOP.” Her response: “To younger voters, the lack of hope and optimism is the most glaring absence in politics today.” Fitzpatrick did polling for the magazine and is quoted in a few subsequent issues offering a conservative voice. “Look, there’s plenty of times where I’ve been in the, you know, quota on any panel. Hey, let’s get a conservative. We’ll call Kellyanne,” Conway says. “But John never made it that way. He was generally interested in why somebody would have a different point of view than most of the people he knew.”

(A staffer also remembers her stopping by the George offices to pass out her business cards and encourage editors to come to her stand-up-comedy shows. Though Conway doesn’t recall this, she says she did one stand-up show in D. C. during that time period. “I totally missed my calling in this world,” she says.)

Kellyanne Conway, Counselor to President Donald Trump, was featured in early issues of George.

MANDEL NGANGetty Images

The mix of politics and pop culture sometimes fell flat. In the 1996 State of the Union address, President Clinton had recommended implementing school uniforms, and the magazine used that as a peg to do a high-fashion photo shoot. “We asked a handful of the fashion industry’s brightest talents to design uniforms that one might be happy to wear instead of enduring the daily ritual of donning the apparel equivalent to Brussels sprouts,” writes David Coleman. The net effect is a forced effort to make a political publication look like a fashion magazine. But features by Norman Mailer on Bill Clinton and Bob Dole during the 1996 campaign hit the mark. (They were also yet another wink at JFK’s presidency: During the 1960 campaign, Mailer had written a pioneering New Journalism profile of Kennedy’s father for Esquire titled “Superman Comes to the Supermarket.”)

George was undoubtedly a major success—one editor says MTV was eager to partner with the magazine early on—but the political-media elite scoffed. White House deputy for intergovernmental affairs John Emerson told the Los Angeles Times in 1996, “Do I read George? I skim George.” An unnamed pundit called the magazine a “net loss of information.” But the magazine’s competitors may have been more threatened than they let on. One night over dinner at the downtown Manhattan hot spot Balthazar, Matt Berman was approached by a Vanity Fair editor who asked what covers George had in the works.

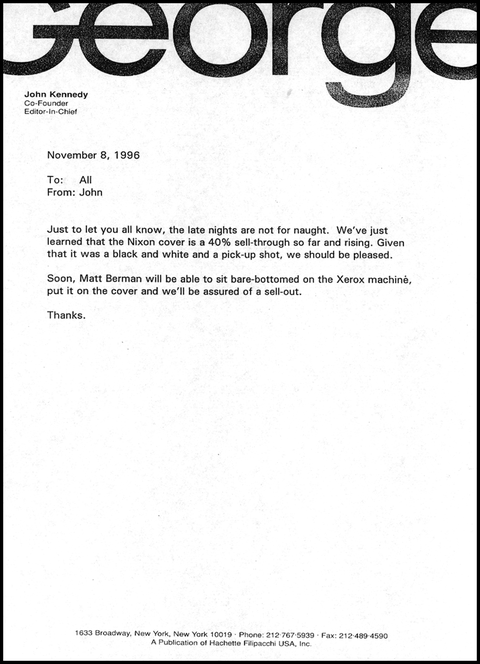

In a November 1996 memo sent to the staff, Kennedy jokes about the success of the magazine.

Courtesy of Matt Berman

“He’s like, ‘You know, I have a fabulous idea for you: You should do Adolf Hitler on the cover.’ He was thinking, Oh, I got this kid art director here. I’m going to try to make a mess,” says Berman, who gave an exaggerated eye roll, then reported it back to Kennedy at the office the next day. “John goes, ‘Oh, right. That’s a great idea. They’d love that over at Vanity Fair.’ They were watching us.”

Kennedy and his staff mostly brushed off criticism and focused on their goal of speaking to a broader audience. He was proudest when readers wrote in to say they’d never really paid attention to politics before but loved George. Kennedy relished the rare industry affirmation when it did come, though.

“I remember later when I got hired at theTimes, John wrote me the nicest note,” says Lindgren, who went on to become the editor of The New York Times Magazine from 2010 to 2013. “He was like, ‘I’m psyched someone from Georgeis working at The New York Times; it’s a validation of what we do here.’ ”

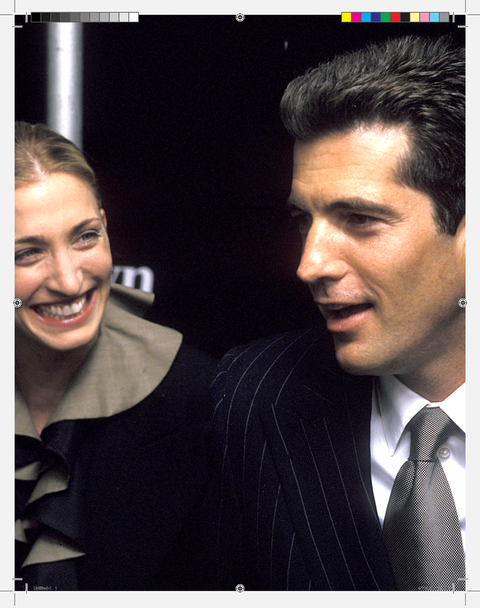

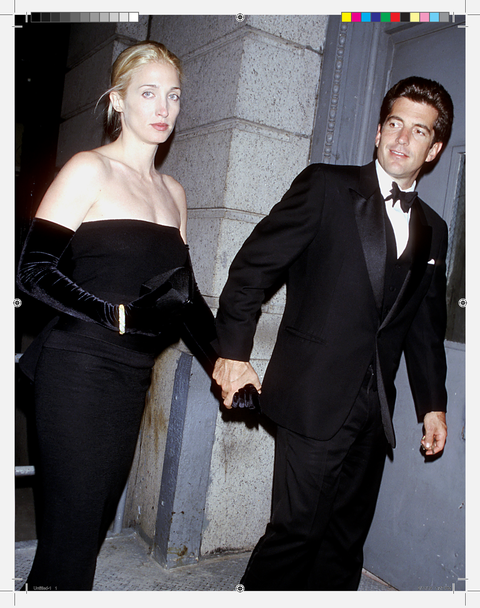

Kennedy and Carolyn Bessette were married in the fall of 1996 without most of the George staff knowing about it.

Ron GalellaGetty Images

As George took off, there was increasing attention placed on Kennedy and Bessette as well. When the time came to plan their wedding, held in the fall of 1996, the couple was desperate to keep the event quiet so that the press wouldn’t get wind of it—Kennedy couldn’t even risk his staff finding out. So Terenzio covered by telling them that Kennedy and Bessette were going to Ireland for a vacation and wouldn’t be reachable for a couple days. When Bessette needed wedding programs, she was afraid to have them done professionally, lest one find its way to a reporter, so she and Terenzio snuck into the George offices late one evening to use the magazine’s printers.

The tactics worked, and Bessette and Kennedy wed on Georgia’s Cumberland Island on September 21, 1996, with no press in sight. The Monday after the ceremony, Kennedy arranged for Terenzio to leave cigars on the male staffers’ desks and Champagne for the women with a note that read: “I just wanted to let you know while you were all toiling away, I went and got myself married. I had to be a bit sneaky for reasons that by now are obvious. I wanted you all to enjoy these small tokens of gratitude and fellowship. You folks all do amazing work and it’s an honor to have you as colleagues.”

Kennedy and Bessette attend a White House Correspondents dinner, where they hosted a table for the magazine.

Ron GalellaGetty Images

That he thought to praise his colleagues in his wedding announcement was classic Kennedy. His staff and friends describe him as kind, funny, and easygoing. He was quick to crack a joke, the first to call to congratulate former staffers on new jobs, and in spite of the paparazzi who constantly trailed him, his preferred mode of transportation around Manhattan remained his bike. The closest anyone comes to a criticism is the observation by a colleague that Kennedy could have a temper—though, they say, he readily admitted mistakes and apologized. But unpretentiousness aside, his star power was undeniable, and dealing with it could be complicated.

“There was this kind of tension where, like, are you working for John or are you working for George? It should’ve been pretty much the same, but it wasn’t invariably,” says Bradley, who replaced Mitchell as executive editor in early 1999.

Kennedy’s relationship with Michael Berman also became an office distraction and eventually the subject of media coverage as their partnership soured. Berman had stepped into the role of publisher, while Kennedy took the head editing role, and Berman’s lack of authority over editorial caused discord.

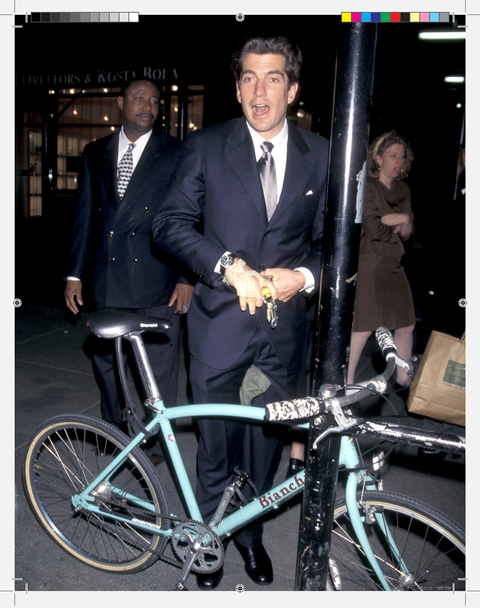

Kennedy's preferred mode of transportation around Manhattan was his bike.

Ron Galella, Ltd.Getty Images

In January 1997, the strain erupted into a physical altercation after a difference of opinion over an article that left Berman’s shirtsleeve ripped. After the incident, Kennedy asked for a locksmith to change the lock on his door. Two days later, he offered Berman a new dress shirt as an apology. Shortly after, however, Berman left his position as the magazine’s publisher, moving to a new movie and television division at Hachette. Kennedy took on a dual role as editor-in-chief and president.

“I don’t know exactly what went down with him and Mike. I mean, maybe I knew at some point and I’ve forgotten, but people do get a little crazy around someone like John,” Lindgren says. “Michael and he, I think, had a really good friendship at some point, and then didn’t, and I think that can be very disturbing to people. They sort of lose their special ‘in,’ and that’s what really fucks people up.”

Berman didn’t respond to repeated requests for comment for this piece. At the time of his departure, he told Keith Kelly, “It was always professional. It wasn’t a dispute so much as a maturing of differences. For me, George was an entrepreneurial idea and a challenge, but it wasn’t anything I expected to stay with throughout my career.”

Kennedy again drew attention away from the magazine when two members of his family made headlines.

Over the decades, nearly a dozen Kennedys have run for office, and how John Jr. would cover his family was a question dating back to George's launch. In a 1995 interview with Larry King, Kennedy said, “If you are going to write about politics, every now and then there is going to be a Kennedy who is going to be doing something and we should write about it. We’re not going to go out of our way. Certainly, there are enough people that write about the Kennedys without us joining in.”

Kennedy addressed a scandal involving his cousin Joe Kennedy II (pictured with his family) in an editor's letter.

Getty Images

But when his cousin Congressman Joe Kennedy II had his marriage annulled and another cousin, Michael Kennedy, was accused of having an affair with a fourteen-year-old babysitter, Kennedy addressed the scandals in his magazine. His September 1997 editor's letter began, “I've learned a lot about temptation recently. But that doesn't make me desire any less. If anything, to be reminded of the possible perils of succumbing to what's forbidden only makes it more alluring.” Kennedy continued: “Two members of my family chased an idealized alternative to their life. One left behind an embittered wife, and another, in what looked to be a hedge against mortality, fell in love with youth and surrendered his judgment in the process. Both became poster boys for bad behavior.

Perhaps they deserved it. Perhaps they should have known better. To whom much is given, much is expected, right? The interesting thing was the ferocious condemnation of their excursions beyond the bounds of acceptable behavior. Since when does someone need to apologize on television for getting divorced?”

“I’ve learned a lot about temptation recently. But that doesn't make me desire any less.”

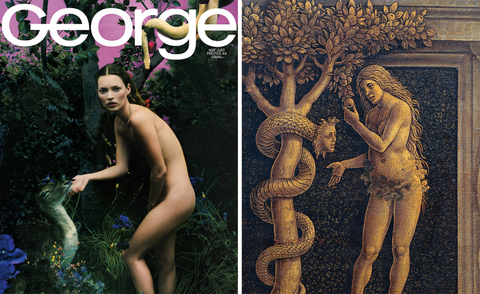

On the cover, Kate Moss appeared nude as Eve. Alongside his letter, Kennedy posed nearly nude, in strategic shadows, gazing up at an apple. Back then, the photo garnered most of the attention and the letter was largely interpreted as a rebuke of his relatives. But today, it reads like a tone-deaf defense of the men, ignoring their privilege and power while being disturbingly dismissive of the women, especially the teenage girl who was the victim of an alleged statutory rape. (The Norfolk district attorney called off the investigation into charges after the babysitter declined to cooperate.)

When asked later about the photo and editor's letter, Kennedy said he didn't regret them. “I did that because that was something I wanted to say and something that I had felt strongly about, which is, we judge harshly people in the public eye for being human. The picture had to accompany the letter because the picture exposed me to judgment,” he told Brill's Content in 1999.

Not long after that issue came out, one of the biggest political stories of the decade broke: President Clinton's relationship with intern Monica Lewinsky. It should have been perfect fodder for the magazine; in fact, Kenneth Starr's September 1998 report revealed that Lewinsky had tried to get a job at George after her time at the White House. But the magazine chose to cover the controversy by having Kennedy interview Gary Hart, another politician brought down by a sex scandal, along with a profile of Clinton confidant Vernon Jordan (who was linked to the Lewinsky story) and a column on workplace sexual harassment.

Kate Moss appeared nude as Eve on the cover of George, while in that issue Kennedy himself appeared nearly nude.

Hearst Magazine Media, Inc., Getty Images

“During the Lewinsky scandal, John had great reluctance to cover that,” says Bradley. “But if you didn't cover it, you kind of would've been completely irrelevant.”

Some of that reluctance may have been due to the fact that Kennedy's father had had multiple affairs while in the White House. When Kennedy was asked at the press conference launching George if the magazine would cover the sex lives of politicians, he admitted, “It would be disingenuous to say I don't have some sensitivity to the seamy side of issues.”

Keith Kelly remembers the Lewinsky story as the beginning of the magazine's decline. “By the end, it seemed to be running out of gas. Advertisers had lost some of the enthusiasm,” he says. “And there was the Clinton scandal with Monica Lewinsky . . . . They didn't really dive into that story. I think he was a little hamstrung by his own family history with those things.” In 1999, even as the economy boomed (the dot-com bust was a couple years away), newsstand sales declined by double digits, though overall circulation, buoyed by subscriptions, was relatively healthy at around four hundred thousand copies per month.

Kennedy's relationship with Pecker was becoming increasingly strained as well. Kennedy was constantly expected to woo advertisers and began to suspect he was being used as bait for other Hachette deals. And Pecker pushed for Kennedy to move into a more public-facing role. Before Michael Berman left, he and Kennedy had come up with an idea for a George TV show with political commentary. Kennedy had no interest in becoming an on-air personality, yet according to two staffers, Pecker was moving forward on a deal for a Kennedy-hosted series with potential partners.

Sources say David Pecker moved forward on a deal for a Kennedy-hosted George TV show, in spite of the fact that Kennedy wasn’t interested in being on-camera.

Getty Images

Pecker wouldn't comment on specific business dealings but tells me, “[Kennedy] had his own vision for George, and he would insist on maintaining that vision. I began to provide more and more advice when the newsstand began to decline . . . . I had several conversations with John about taking more risks editorially.”

In February 1999, Pecker unexpectedly left Hachette for American Media, Inc. At that point, George, nearing its four-year anniversary, had a loyal audience, with one of the strongest subscription-renewal rates within the company, but it had never made money. (This was not necessarily unusual for a new magazine in that era; patient and/or profligate publishers—notably Condé Nast—sometimes waited quite a bit longer to see titles make it into the black.) Kennedy was becoming frustrated with Hachette, but when he met with the new president and CEO, Jack Kliger, in June 1999, he was open to discussing plans to make the magazine profitable.

Jack Kliger took over Hachette with David Pecker left in 1999. He worked with Kennedy on a business plan.

Getty Images

“Figuring out how to make it work well for both of us was a priority,” Kliger says. “When I got to Hachette, I was hired with an awful lot of issues, including George and Mirabella, and also I was following a CEO named David Pecker, who left us with a lot of stuff to clean up. You could put it that way.”

According to Kliger, Kennedy put together a strategy to reduce frequency, rein in costs, and increase George's digital presence. (The magazine had had a website since its 1995 launch, but a look at archived versions shows it mostly served as a home for print stories, and the editors say it wasn't a priority.) Kliger says he was never aware of talk of TV deals but that Kennedy made it clear he didn't want his family name to be exploited. “John always expressed a concern about being used as a bird in a gilded cage. That was his phrase.”

While efforts were made to reinvigorate the magazine's business, on the editorial side, Kennedy was preparing for one of his biggest interviews yet: a sit-down with Fidel Castro in Cuba. He'd done a pre-interview with Castro and was planning to go back to Cuba for New Year's weekend to talk to him on the record.

That interview never happened. On July 16, 1999, Kennedy was flying his wife and her sister Lauren to Martha's Vineyard for his cousin Rory's wedding. At some point in the night, the plane crashed nose-first into the Atlantic Ocean.

Kennedy snapped this photo of creative director Matt Berman, author of JFK Jr., George, & Me.

Courtesy of Matt Berman

Terenzio was the first member of the George staff to learn the editor had gone missing. She was staying at his TriBeCa apartment because her air-conditioner was broken. A little after midnight, she got a call from Carole Radziwill, a relative of Kennedy's who was trying to get in touch with the couple. Radziwill explained that a friend who was supposed to pick up Kennedy and the Bessettes at the Vineyard airport had told the family they'd never arrived. After trying to call Kennedy's flight instructor, nearby airports, and some of his friends and relatives, Terenzio called Matt Berman, who was planning to fly to Los Angeles in the morning to shoot Rob Lowe for the next cover.

“You can't go to L. A.,” she said. “John never landed last night.”

Berman switched his flight to 11:00 a.m. and left to meet Terenzio at Kennedy's loft. Hours passed without any news. Berman then pushed his flight to 1:00 p.m. and told Lowe's team only the photographer would be at the shoot. As the day wore on, newscasters began to describe Kennedy and the Bessettes as officially lost, and Berman took a cab up to the George offices. That afternoon and the weeks that followed are now a blur, he says. The bodies of Kennedy, Bessette, and her sister were found six days after their disappearance.

“There was this sort of sense of sad sorrow but also purposelessness. What the hell do we do now? What's the point?” says Bradley, who was the executive editor at that time. There was the practical question of what to do about the next issue of the magazine, but also the chaos of the news cycle in which they were now the center.

“We were very protective of him and his privacy, and then that suddenly became moot. The entire country, world, was talking about what happened to John and Carolyn and Lauren. Here we were, the people who professionally knew him better than anyone, and we didn't feel like we could say a word about it,” Bradley says. “We were told that we couldn't say a word about it by Rose [Terenzio], who told the staff that this was what Caroline Kennedy wanted, and Caroline was the significant owner of the magazine at the time when John died.” (Terenzio says she doesn't remember Caroline giving that directive.)

Kliger, who'd only been on the job for a little more than a month, instructed the team to move forward with their work and assured them the magazine would continue without Kennedy. According to Kliger, he had the backing of Hachette's owner, Jean-Luc Lagardère: “His first comment after I confirmed to him that John had passed away is 'Well, we're not going to close the magazine. I'm not going to leave that as his legacy that it was closed immediately following his death, so we will continue publishing and we'll see what happens.' ”

Getty Images

After Hachette bought the Kennedy family's 50 percent stake in the magazine, Kliger began taking meetings with possible new editors-in-chief. The New York Times wrote, “The position of editor-in-chief at George has probably been the most difficult job to fill in the magazine industry this year, if not this decade. After all, who would want to step into a role established by a favorite son of America?”

But Kliger says he had plenty of interest, including from Al Franken, the comedian who would later become a senator. “I was willing to meet with Franken, just because he expressed interest. He had, of course, a career with Saturday Night Live. He knew what journalism and writing were about, but at the meeting, Jean-Luc said, 'No. We have to have somebody that knows how to put out a periodic magazine from both a journalistic as well as an editorial-operations point of view.' I agreed.”

Kliger eventually offered the job to Frank Lalli, a former managing editor of Money magazine.

“I not only read the prospectus, but they sent over the last year's worth of the magazine and I looked at them very, very carefully,” Lalli says. “I don't think John was fulfilling the prospectus he wrote. I don't think he had the staff to fulfill it. So what I brought to it was a kind of editorial expertise that John didn't have.”

The staff underwent an overhaul after Lalli arrived. He ended the contracts of columnists Ann Coulter and Paul Begala, whom Kennedy had signed up earlier that year; Lalli felt they were too partisan. He says the relationship with Coulter ended after he refused to run a column because he found it to be homophobic.

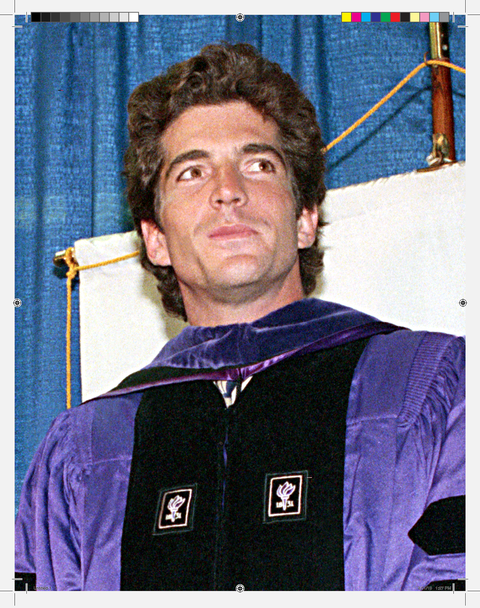

Former Money magazine managing editor Frank Lalli (right, pictured with John Watters and Patty Hearst) took over George after Kennedy died in 1999. He says he met with Caroline Kennedy before being offered the job.

Getty Images

“I got rid of more than half of the staff in six months. A lot were emotionally spent; others weren't very good at all, actually,” Lalli says. “One of John's really good friends told me later, 'You know John took in strays.' So then, little by little, I put together the staff we wanted to put together. And we did some really good journalism.”

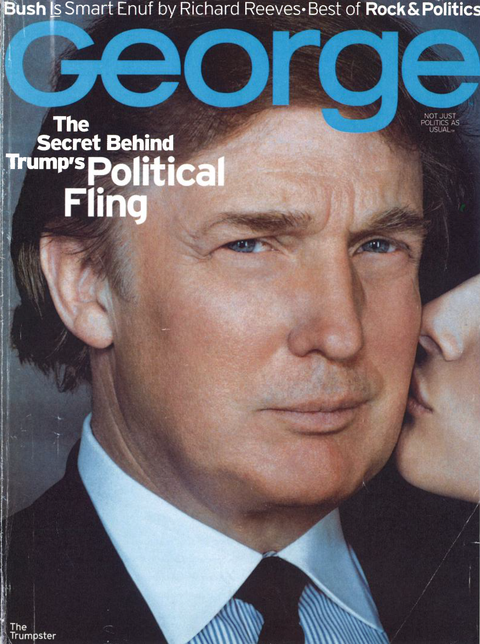

Lalli's first issue hit newsstands in March 2000, featuring Donald Trump on the cover with the headline “The Secret Behind Trump's Political Fling.” Lalli says the idea came from someone on the business side of the magazine who knew Trump. (Pecker, who'd already left Hachette, wasn't involved with the cover.) At the time, Trump was a famous but often ridiculed real estate developer with multiple bankruptcies on his résumé who hadn’t yet starred on The Apprentice. He was someone who appeared more in tabloid gossip columns than on the business pages, which is why former George staffers believe Kennedy wouldn't have put him on the cover.

Donald Trump appeared on the cover of Frank Lalli's first issue of George after Kennedy's death.

Hearst Magazine Media, Inc.

“I remember we went to Trump Tower and we did a portrait of Melania and him. He did have his hand on her ass the whole time, squeezing it. I'm thinking, This is so gross,” says Matt Berman, who left the magazine shortly after that shoot. “There were always people that you're constantly . . . They're orbiting. There were probably just scraps of people after John passed away. I was in a daze by then. I'll tell you, John would've never put him on the cover.”

Bradley, who left around the same time Lalli started, says, “Trump would not have been someone that we'd put on the cover, because there was nothing about Trump that represented what John believed in.” Bradley describes the new editorial team as “a group of people who were determined basically to say, 'Fuck you' to what the old guard did and establish their independence and announce that they weren't going to be chained to John Kennedy's vision for the magazine.”

The new George featured a piece on Elián González, the Cuban boy who was embroiled in a charged custody battle, which garnered a lot of attention. And Lalli says he was proud of landing a cover interview with Linda Tripp, the former confidante of Monica Lewinsky's who had betrayed her. “I saw that and I was like, 'Oh my God, John is spinning in his grave like a top,' ” says Bradley.

Though newsstand sales increased under Lalli, advertising revenue continued to drop, and nearly eighteen months after Kennedy's death, George folded. Kliger says, “We just came to the conclusion that we tried, we gave it a shot, we spent some money. At that point, we just had to focus on our core businesses and we couldn't see how we could get George to be in that ring. It was a tough decision.”

One question that has lingered over the two decades since Kennedy's death is: Would he have eventually followed in the footsteps of so many of his relatives and run for office? It came up in nearly every interview he sat for, and he always deflected with a joke like “I've never been asked that!” Many colleagues of his whom I spoke with believe he would have done so—but not until the magazine was healthy enough to survive without him.

“My feeling was always that George was a way of testing the waters for him, to kind of turn the tables on the people who would be asking questions about him if he ran for office and sort of get a perspective on it,” Bradley says. “I thought that was kind of a genius thing to do.”

Getty Images

Had Kennedy had been able to leave George on a solid foundation before entering, say, a Senate race, what might that have looked like? “My mind's thinking is that if that magazine would have kept publishing, it would have been the perfect magazine for the times we're in,” Kliger says. “It would have been a magazine more squarely about politics and the consciousness of a millennial generation. I think Beto O'Rourke and Elizabeth Warren would have been on the cover. It was a great concept ahead of its time. I wish we would have been able to stick with it because I think it would be a very relevant and needed product today. I think the times have come to George.”

Maybe. But maybe that would have been a double-edged sword. Certainly the magazine would have faced unprecedented competition from emerging digital media outlets like BuzzFeed News and The Daily Beast, not to mention lifestyle publications like Teen Vogue, Elle, and GQ, which help drive the political conversation today. In fact, it's difficult to name a title aiming for an audience broader than Cat Fancy's which doesn't touch on politics.

“Not only can coverage of politics and pop culture go together, they have to go together. It really is the lens through which you have to view the world,” says Noah Shachtman, the editor in chief of The Daily Beast. “Our core mission is we explore politics and pop culture and power. It's what we do, yeah, it's definitely part of the mission.”

Some of Kennedy's colleagues believe he would have eventually run for political office after getting George on solid footing.

Courtesy of Matt Berman

Kennedy may have foreseen the changing media landscape. But today's political journalists don't point to George as the catalyst. “I'm not sure it has [a legacy],” says CNN's Jake Tapper, who wrote an article for George about the future of transportation. “I don't think very much in journalism has a legacy. We all just do the best job we can and what we do is important but journalism is ephemeral and it's the people we cover that matter, not us.”

There is also a big difference between George's relatively bipartisan point of view and today's polarization, especially now that Trump has raised the political stakes and soft, glossy coverage of the president and his administration would draw accusations that the indefensible was being normalized. And celebrities who want to be a part of the political conversation are now expected to be informed about the policies of whomever they're lending their support to. Remember the outcry when Kanye West showed up at the White House? A light-hearted “If I Were President” celebrity column like the one George featured would be a lightning rod today. Maybe in the last two decades the culture caught up to George, but then a proudly provocative reality TV star president gave new meaning to the tagline “Not just politics as usual.”

“George tried to liven up politics,” says MSNBC's Hardball host Chris Matthews, who wrote for the first issue of George about the ways in which Congress is like high school. “I personally think you don't have to colorize politics anymore. I think [Kennedy] probably thought the stiff shirts have to be colorized, that they needed to give it some MSG.

“Today we know we've got plenty of that. We're not looking to sexy it up.”

No comments:

Post a Comment