My long expected grand transition to EV has now fully begun. Battery technology is now close enough to been good enough to trigger the investment.

Better yet improvement is always easily retrofitted with the next battery change out.

The manufacturers now have ample experience in both manufacture and down stream supply as well. Thus the shift to massive production in which suddenly a whole generation of cars arrive in your showroom.

Yet it is still a transition vehicle before we actually start using the original TESLA motor that draws its power from free electron decay in Dark Matter. The shift there will be even easier with our present electric infrastructure..

Big carmakers are placing vast bets on electric vehicles

From GM and Geely to Mitsubishi and Mercedes, giants of the industry are making battery-powered plans

https://www.economist.com/business/2019/04/17/big-carmakers-are-placing-vast-bets-on-electric-vehicles

IN 1900 ONE in three

cars on American roads ran on volts. Then oil began gushing out of

Texas. Cheaper than batteries, and easier to top up, petrol fuelled the

rise of mass-produced automobiles. Cost and worries about limited range

have kept electric vehicles (EVs) in a niche ever since.

Tesla, which has made battery power sexy again in the past decade,

produced just 250,000 units last year, a fraction of what Volkswagen or

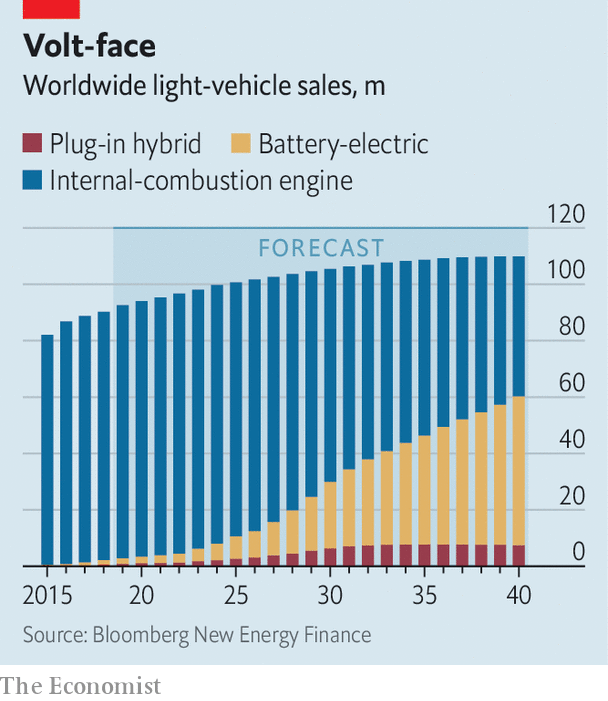

Toyota churn out annually. For every one of the 2m or so pure EVs and plug-in hybrids, which combine batteries and internal-combustion engines (ICEs), sold in 2018, the world’s carmakers shifted 50 petrol or diesel cars.

EV sales

are, however, accelerating as quickly as electric motors themselves.

Some industry-watchers reckon that they will account for nearly 15% of

the global total by 2025. By then, one in five new cars in China will

run on batteries, according to Bloomberg New Energy Finance, a

consultancy. The chief reason such optimistic forecasts no longer look

outlandish is the entry into the electric race of the car industry’s

juggernauts. A survey by Reuters in January put the industry’s total

planned EV-related spending worldwide (including on batteries) at around $300bn over the next five to ten years. From GM and

Geely to Mercedes and Nissan, big carmakers all want to turn out

millions of such cars—and turn a profit doing so. Their strategies range

from cautious to headstrong.

Making a profitable, mass-produced EV has proved elusive. A battery powertrain can be three times the price of an ICE. But a combination of better technology and greater scale may soon allow EVs

to compete on price with petrol vehicles, and enable motorists to drive

long distances without the fear of running out of juice.

They had

better, carmakers are hoping. Worries about climate change and air

pollution are prompting authorities around the world to consider phasing

out new petrol and diesel engines in the coming decade. In the absence

of federal regulations under America’s climate-sceptical president,

Donald Trump, some progressive cities and states there are tightening

local rules. Fiat Chrysler (whose chairman, John Elkann, sits on the

board of The Economist’s parent company) has

just agreed to pay Tesla hundreds of millions of euros to count the

Californian marque as part of its fleet, and thus avoid steep fines for

exceeding average CO2-emissions standards for carmakers due to come into force in the European Union next year. In China, where half the world’s EVs

are already sold, the government sees the electrification of transport

as a way to combat choking urban smog—and to overtake the West

technologically.

Western premium brands appear best positioned to

take an early lead. While batteries remain pricey, fancy marques can

offset the cost with the higher prices that their vehicles command.

Jaguar and Audi have already broken Tesla’s monopoly at the lucrative

top end of the market. Daimler, which owns Mercedes, has committed €10bn

($11.3bn) to its EQ range and wants 20% of its cars to be fully electric by 2025.

Daimler and BMW,

which has been bruised by losses on its poorly selling i3 electric

hatchback, are hedging their bets by backing platforms—the basic

architecture of a car—that are able to accommodate petrol and diesel

engines as well as electric motors. This should help them contain costs,

by avoiding duplication, but involves compromises over battery size and

layout. Sacrificing range and interior space in this way may dent

brands built on luxury and technological prowess, says Patrick Hummel

of UBS, a bank.

Many mass-market firms are likewise

proceeding cautiously. Their thinner margins leave less room to absorb

the cost of batteries. Renault of France and South Korea’s Hyundai are

nevertheless toying with the idea of a dedicated electric-only

platform. PSA Group has said it plans to electrify more

Peugeots, Citroëns and Opels. Fiat Chrysler has made similar noises,

though the Tesla tie-up suggests its near-term plans are less ambitious.

Toyota’s early bet on hydrogen fuel cells, which lag behind batteries

on the road to widespread adoption, had long been a distraction. The

Japanese giant has now acknowledged that buyers want battery power. It

is planning ten models by the early 2020s.

The most daring by a long way is VW. The German group’s heft—it produces 10m cars a year—affords it economies of scale only Toyota could hope to match. The €30bn VW plans to spend on developing EVs

over the next five years, plus €50bn to fit them with batteries, leaves

all other carmakers in the dust. In March Herbert Diess, its chief

executive, promised 70 new electric models by 2028, rather than 50 as

previously pledged, and 22m EVS delivered over the next

ten years. The company is contemplating a huge investment in a

“gigafactory” to supply its own batteries rather than depending on

outside suppliers.

VW is already developing a dedicated platform and converting entire factories to EV production. The first, at Zwickau in Germany, will eventually turn out 330,000 cars a year for the VW brand as well as Audi and SEAT. Its medium-sized ID hatchback,

to be shipped next year, will cost around €30,000, similar to an

equivalent diesel-powered Golf, and travel 400-600km (250-370 miles) on a

single charge. On April 14th in Shanghai Mr Diess unveiled a

sport-utility vehicle to compete with Tesla’s snazzy Model X in China from 2021. Once the range of EVs reaches full production in 2022, VW believes,

such models will start breaking even. By 2025, when it hopes

one-quarter of its output will be electric, they should be as profitable

as petrol cars.

As Mike Manley, boss of Fiat Chrysler, observers, it is no longer a question of whether carmakers can supply a fleet of EVs but whether people will pay for them. If governments withdraw generous subsidies which EV-owners

have enjoyed, charging infrastructure fails to materialise or electric

cars’ pitiful resale value does not increase, motorists may be reluctant

to switch to battery power. Poor sales, combined with the large upfront

investments, would hit carmakers’ margins, which for mass-market brands

are already about as exciting as a Soviet-era Trabant in mud brown. The

financial consequences could be “ugly”, warns Bernstein, an

equity-research firm.

Electric field

At the same time, the big carmakers can expect more competition from rivals unburdened by complex ICE supply

chains and large workforces. vw has 40,000 suppliers worldwide and

directly employs 660,000 people. Lower capital intensity, and the

relative simplicity of EVs, which use many fewer parts

than petrol vehicles and are easier to assemble, is drawing in upstarts.

They include Dyson, a British maker of vacuum cleaners, and a series of

Chinese Tesla-wannabes, such as NIO and Byton. Bigger Chinese carmakers, such as Geely and JAC, have also developed expertise in EVs. With domestic sales stalling, they are beginning to eye export markets.

Other

technological bumps are meanwhile starting to test the industry’s

chassis. Self-driving cars and ride-sharing are forcing companies to

rethink their established business model. Investing in EVs

now leaves them with less to spend on adapting to everything else. They

may be hoping that the electric race will serve as a practice lap for

wider oncoming disruption.

No comments:

Post a Comment