What this truly confirms is that the Trojan War was never in the Aegean. Trojan princes were not taking large fleets from Asia Minor to the Levant to conduct a war of conquest while leaving their flank open to adventurous Greek Warlords. Those warlords were not combining to attack Troy in the face of such a fleet either.

In fact this prince is Trojan only because he is from Asia minor in the right time and place that archeologists believe is Troy. This is known as a fundamental error.

As i have posted in the past, thanks to author Da Vinci, the Trojan War took place about this time in the Baltic. That was around 1178 - 1180 BC as confirmed by star locations reported in the Iliad itself.

What then happened is that in 1159 BC we had a massive economic collapse that ended northern agriculture and the whole Atlantean world as well. This broke the power of the Sea Peoples in particular and triggered a desperate movement of peoples south to the Aegean known now as the Dorian invasion. They happily renamed towns after their homeland towns. Their own fleet made the trip around the European mainland in order to join their peoples and support their invasion.

This important inscription makes it clear that the navel resource there would prevent a so called Trojan War. Recall that the Iliad speaks of no such navy at all. What we have conforms well to Baltic conditions in which a confederation of essentially sea side communities decide to beat up a fortified wealthy town and struggle with it. .

11 October, 2017 - 13:46

Theodoros Karasavvas

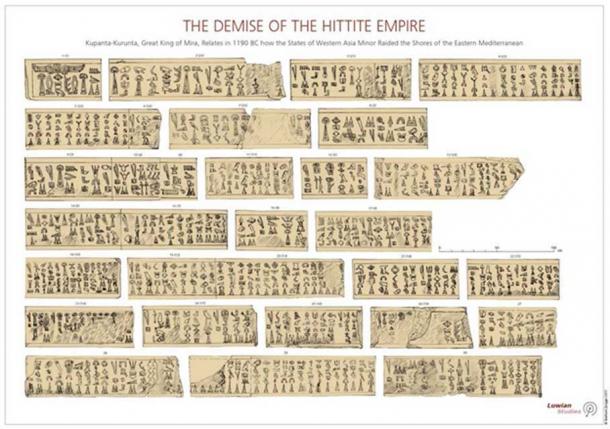

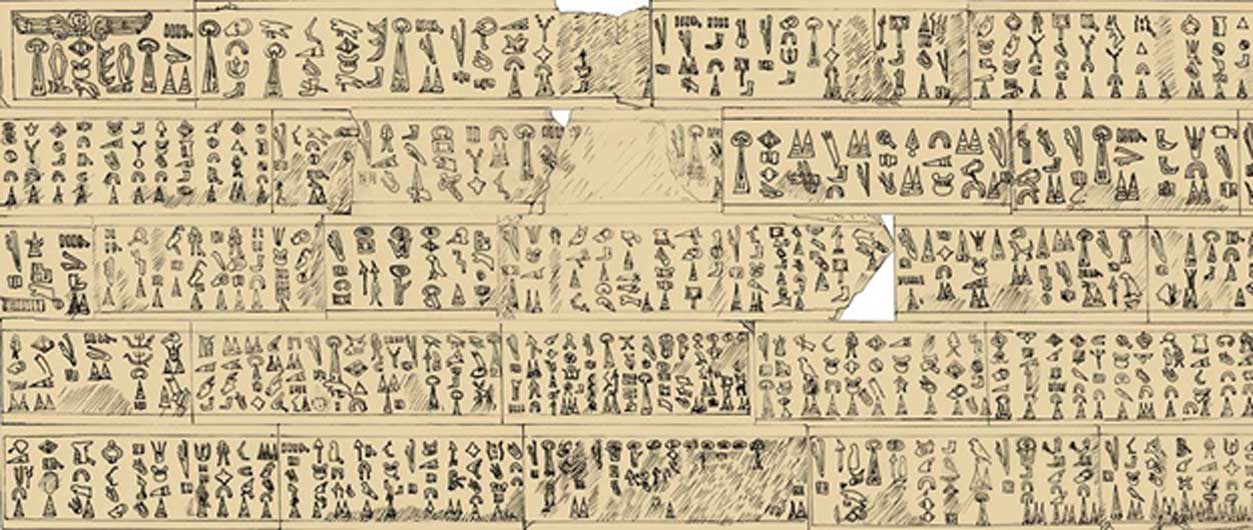

3,200-Year-Old Stone Inscription Narrates the Tales of Sea People and a Trojan Prince

A

group of Swiss and Dutch archaeologists have announced the rediscovery

of a 29-meter-long (95 ft) Luwian hieroglyphic inscription that

supposedly narrates the tales of mysterious “Sea People” and a warring

Trojan Prince in the Eastern Mediterranean. According to the experts, it

bears the longest known hieroglyphic inscription from the Bronze Age.

One of the Longest Hieroglyphic Inscriptions Ever Found May Have Been Deciphered

Live Science reports

that a 3,200-year-old mysterious stone was etched in a forgotten

language called Luwian, which fewer than two dozen people understand

worldwide. One of those scholars is Fred Woudhuizen, an independent

academic, who claims that he has now deciphered the meaning of the long

and elaborate inscription. According to Woudhuizen, the inscription

narrates the story of a prince named Muksus from Troy and his military

exploits, while it also mentions the enigmatic “Sea People”

confederation (who also appear in other inscriptions). The decryption

goes on to claim Mira, which was located in what is now western Turkey

and controlled Troy itself, was ruled by a King Kupanta-kuruntas. Prince

Muksus, a Trojan prince, led a naval expedition for Mira that conquered

Ashkelon, now in modern-day Israel, and built a fortress there, the

inscription says, according to Woudhuizen..

Image of the James Mellaart copy of the Luwian inscription (Image: James Mellaart/ Luwian Studies )

The text also tells of King Kupanta-kuruntas' rise to the throne of

Mira. After a Trojan king named Walmus was overthrown, Kupanta-kuruntas'

father King Mashuittas seized control of Troy. Mashuittas quickly

reinstated Walmus to the throne of the Bronze Age city in exchange for

his loyalty to Mira. Once his father died, Kupanta-kuruntas became king

of Mira, though he was never the official king of Troy. The ancient

leader instead describes himself in the text – always according to

Woudhuizen – as a guardian of Troy, asking future rulers to guard Wilusa

(an ancient name for Troy) like the great king of Mira did.

The Original Discovery

We should note here, that the discovery of the 29-meter-long (95

feet) Luwian hieroglyphic inscription took place almost 140 years ago.

When in 1878, villagers in Beyköy – a small town in the central district

of Düzce Province in Turkey – discovered the large and peculiar

artifact in pieces in the ground, they probably couldn’t imagine the

immense archaeological importance of the find as Live Science reports .

Despite seeing that the artifact was inscribed with illegible

pictograms and scribbles, the local peasants decided to use the stones

as building material for the foundation of their mosque. Luckily for

archaeology though, French archaeologist Georges Perrot managed to

carefully copy the inscription before the valuable artifact was totally

destroyed.

Several Scholars Remain Skeptical of the Inscription’s Authenticity

Many critics challenge the inscription’s authenticity already. One of

the reasons why so many scholars remain skeptical, is that the

inscription itself no longer exists, being destroyed back in the 19th

century. However, records of the inscription, including a copy of it,

were found in the estate of James Mellaart, a decorated archaeologist

who died in 2012.

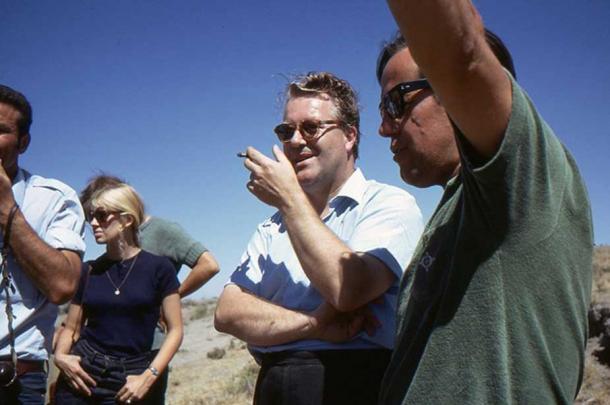

The controversial British archaeologist James

Mellaart in the middle, smoking a cigarette at the neolithic site of

Çatalhöyük in Turkey. ( CC BY-SA 3.0 )

As Live Science reports ,

according to Mellaart's notes, the inscription was copied in 1878 by a

French archaeologist named Georges Perrot as we already mentioned. Soon

after of the inscription was used as building material for the mosque,

Turkish authorities searched the village and discovered three inscribed

bronze tablets that are now missing. The bronze tablets were never

published and for that reason archaeologists don’t know what they said. A

scholar named Bahadır Alkım rediscovered Perrot's drawing of the

inscription and made a copy, which Mellaart would also copy and from

which the Swiss-Dutch team deciphered the text.

Multiple Copies

As one easily understands, the copy that Woudhuizen claims to have

deciphered, isn’t the original copy of the authentic inscription, a fact

that makes things very complicated. Live Science contacted many scholars

not affiliated with the research, and several expressed concern that

the inscription may be a hoax. Some have accused Mellaart of

intentionally spreading a modern forgery, and since no physical records

of the inscription have been found, we will never be sure if any of

these writings are authentic.

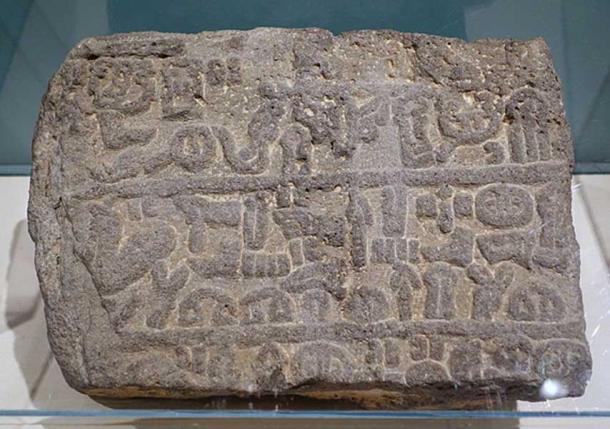

Inscription in hieroglyphic Luwian script, Amuq Valley, Jisr el Hadid, University of Chicago . ( Public Domain )

On the other hand, Woudhuizen and Eberhard Zangger, a geoarchaeologist who is president of the Luwian Studies foundation ,

claim that as of now there’s no way to tell with confidence if the

inscriptions were authentic or not. Regardless, they added that it would

have been very difficult for Mellaart to pull off a forgery of this

caliber, as Luwian language was barely deciphered for the first time in

the 1950s. They also wonder why Mellaart would go that far to construct

such a complicated forgery, when in reality he never published anything

or had any profit from this whole situation.

The findings will be published in an upcoming December edition of the

Proceedings of the Dutch Archaeological and Historical Society.

Top image: Luwian Hieroglyphic inscription by the Great King of Mira, Kupanta-Kurunta, composed at about 1180 BC. Image: Luwian Studies

No comments:

Post a Comment