This appears to provide a path forward toward the goal of curing diabetes. It was one of the obvious targets and promise of stem cell therapy. Still it is a small step.

Yet it may provide a temporary improvement for victims as well. That could then allow a reversal of side effects.

What is quite remarkable is just how difficult something so elegant as the stem cell happens to be. We also now live in an age in which science is learning to add information as well. All good..

Mice with diabetes "functionally cured" using new stem cell therapy

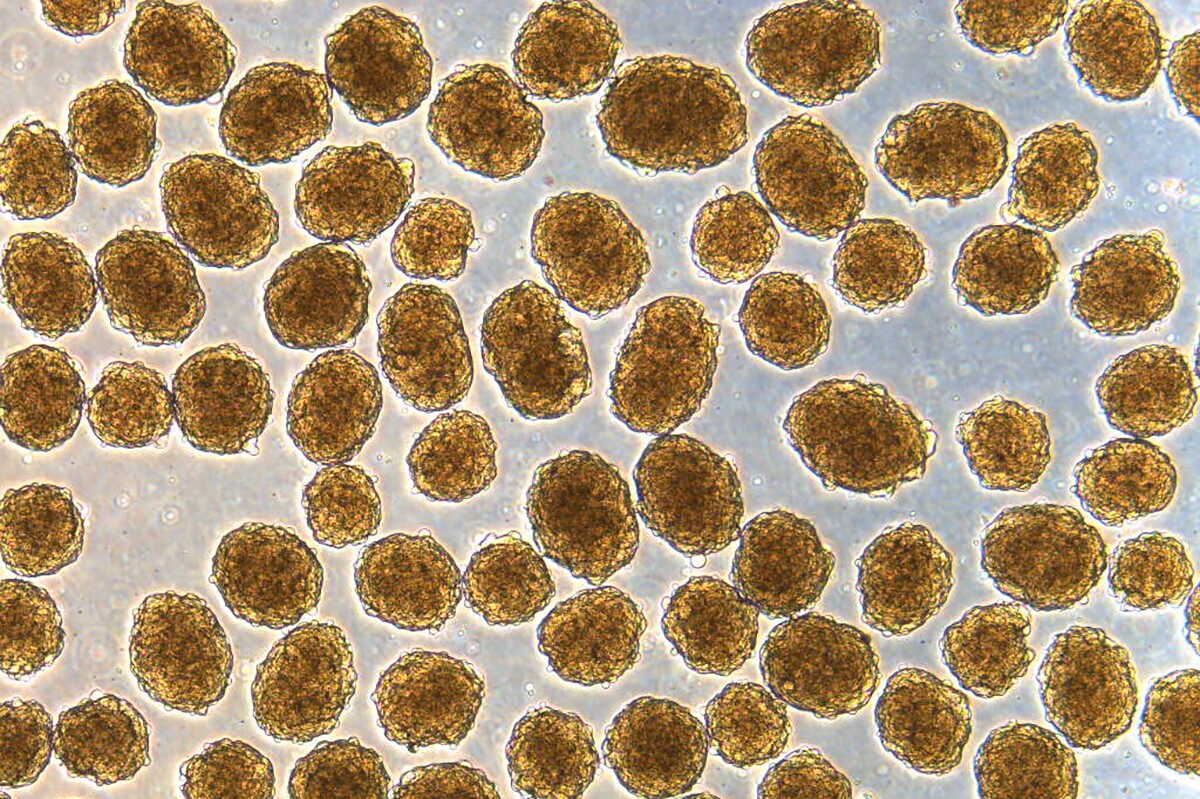

Clusters of insulin-producing beta cells, which were produced from stem cells and used to functionally cure mice of diabetes

Millman Laboratory

Diabetes is characterized by trouble producing or managing insulin, and one emerging treatment involves converting stem cells into beta cells

that secrete the hormone. Now, scientists have developed a more

efficient method of doing just that, and found that implanting these

cells in diabetic mice functionally cured them of the disease.

The study builds on past research by the same team, led by Jeffrey Millman at Washington University. The researchers have previously shown that infusing mice with these cells works to treat diabetes, but the new work has had even more impressive results.

“These mice had very severe diabetes with blood sugar readings of more than 500 milligrams per deciliter of blood — levels that could be fatal for a person — and when we gave the mice the insulin-secreting cells, within two weeks their blood glucose levels had returned to normal and stayed that way for many months,” says Millman.

Insulin is normally produced by beta cells in the pancreas, but in people with diabetes these cells don’t produce enough of the hormone. The condition is usually managed by directly injecting insulin into the bloodstream when it’s needed. But in recent years, researchers have found ways to convert human stem cells into beta cells, which can pick up the slack and produce more insulin.

In the new study, the team improved that technique. Usually when converting stem cells into a specific type of cell, a few random mistakes are made, so some other types of cells end up in the mix. These are harmless, but aren’t exactly pulling their weight for the job at hand.

“The more off-target cells you get, the less therapeutically relevant cells you have,” says Millman. “You need about a billion beta cells to cure a person of diabetes. But if a quarter of the cells you make are actually liver cells or other pancreas cells, instead of needing a billion cells, you’ll need 1.25 billion cells. It makes curing the disease 25 percent more difficult.”

So, the new method was focused on reducing those unwanted extras. By targeting the cytoskeleton, the underlying structure that gives cells their shape, the team was able to not only produce a higher percentage of beta cells, but they also functioned better.

“It’s a completely different approach, fundamentally different in the way we go about it,” said Millman. “Previously, we would identify various proteins and factors and sprinkle them on the cells to see what would happen. As we have better understood the signals, we’ve been able to make that process less random.”

When these new-and-improved beta cells were infused into diabetic mice, their blood sugar levels were stabilized, rendering the diabetes “functionally cured” for up to nine months.

Of course, at this stage it’s just an animal trial, so the results may not translate to humans any time soon, if ever. But the researchers plan to continue the work by testing the cells in larger animals over longer periods, with hopes of one day getting the treatment ready for human clinical trials.

The research was published in the journal Nature Biotechnology.

Source: Washington University

The study builds on past research by the same team, led by Jeffrey Millman at Washington University. The researchers have previously shown that infusing mice with these cells works to treat diabetes, but the new work has had even more impressive results.

“These mice had very severe diabetes with blood sugar readings of more than 500 milligrams per deciliter of blood — levels that could be fatal for a person — and when we gave the mice the insulin-secreting cells, within two weeks their blood glucose levels had returned to normal and stayed that way for many months,” says Millman.

Insulin is normally produced by beta cells in the pancreas, but in people with diabetes these cells don’t produce enough of the hormone. The condition is usually managed by directly injecting insulin into the bloodstream when it’s needed. But in recent years, researchers have found ways to convert human stem cells into beta cells, which can pick up the slack and produce more insulin.

In the new study, the team improved that technique. Usually when converting stem cells into a specific type of cell, a few random mistakes are made, so some other types of cells end up in the mix. These are harmless, but aren’t exactly pulling their weight for the job at hand.

“The more off-target cells you get, the less therapeutically relevant cells you have,” says Millman. “You need about a billion beta cells to cure a person of diabetes. But if a quarter of the cells you make are actually liver cells or other pancreas cells, instead of needing a billion cells, you’ll need 1.25 billion cells. It makes curing the disease 25 percent more difficult.”

So, the new method was focused on reducing those unwanted extras. By targeting the cytoskeleton, the underlying structure that gives cells their shape, the team was able to not only produce a higher percentage of beta cells, but they also functioned better.

“It’s a completely different approach, fundamentally different in the way we go about it,” said Millman. “Previously, we would identify various proteins and factors and sprinkle them on the cells to see what would happen. As we have better understood the signals, we’ve been able to make that process less random.”

When these new-and-improved beta cells were infused into diabetic mice, their blood sugar levels were stabilized, rendering the diabetes “functionally cured” for up to nine months.

Of course, at this stage it’s just an animal trial, so the results may not translate to humans any time soon, if ever. But the researchers plan to continue the work by testing the cells in larger animals over longer periods, with hopes of one day getting the treatment ready for human clinical trials.

The research was published in the journal Nature Biotechnology.

Source: Washington University

No comments:

Post a Comment