First off, visiting any national park in particular is an all day superb experience. It a great product fully appreciated and totally accessable.

what it never had was 24/7 media advertising. This has now changed organically through selfies. We all do it now and we share it.

Great product and no advertising budget. Now it is a great product with an organic advestising budget. This is ongoing and the powers that be need to plow coin in to expand facilities.

Great product and no advertising budget. Now it is a great product with an organic advestising budget. This is ongoing and the powers that be need to plow coin in to expand facilities.

This is called a welcome unintended consequence.

A New Study Finds Crowds at National Parks May Be Due to Social Media

But popularity online could also be the ticket to better funding for parks with lower engagement

(Photo: NPS)

Published Jun 4, 2024

Wes Siler runs Indefinitely Wild, Outside's lifestyle column telling the story of adventure-travel in the outdoors, the vehicles and gear that get us there, and the people we meet along the way.

https://www.outsideonline.com/outdoor-adventure/exploration-survival/national-parks-social-media/

Heading out the door? Read this article on the Outside app available now on iOS devices for members! Download the app.

Every week I read a new story about tourists doing something stupid on their phone in a national park. It’s hard not to come away from the endless onslaught of touron news with the idea that social media is ruining our public land. But is there any empirical evidence for that? And isn’t visitation good for paying to keep our national parks in pristine condition?

A study published by the National Academy of Sciences draws a significant link between social media exposure and visitation at individual national parks. It’s not a surprise that parks with ample shared photographs, videos, and geotags are more popular than parks without, but the study is able to demonstrate that even the most popular parks can still feel the effects of popularity on X/Twitter and Instagram. It provides a statistical model to suggest that the connection between social media and visitation offers lessons the NPS and its stakeholders could use to help address core issues like overcrowding and easing its enormous deferred maintenance backlog.

What Did the Study Find?

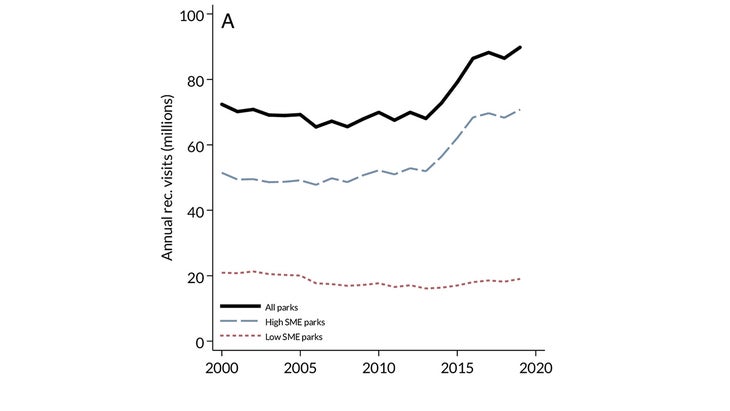

Between 2010 and 2020, total visitors to national parks increased from 70 to 90 million annual people. Much of this use has been concentrated in a handful of the most famous parks like Yellowstone, Yosemite, and the Grand Canyon, and increases elsewhere are less predictable.

Total NPS visitation 2000 to 2020. (Photo: Casey Wichman)

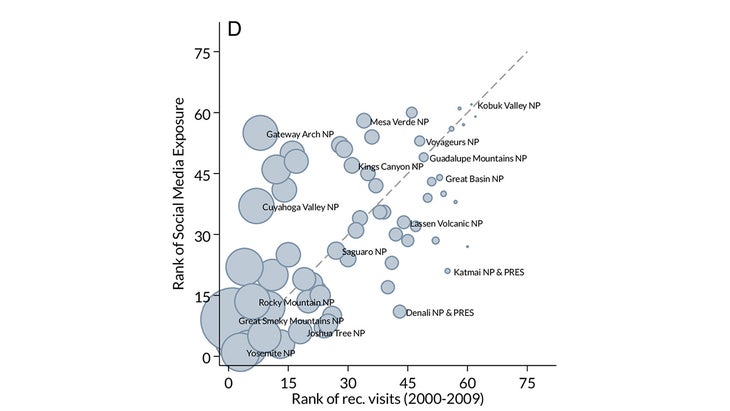

Visitation to California’s Joshua Tree National Park, for example, has increased by 2.5 times since 2000, but in that same time, the number people making a trip to Guadalupe Mountains National Park in Texas or Voyageurs National Park in Minnesota has remained flat.

It’s tempting to try and attribute that to geography, seasonal weather, proximity to major metropolitan centers or ease of visitation. But remember we’re talking about rates of visitation, not the outright number. As more and more people visit parks, why are they concentrating their use in the same areas?

What Can This Tell Us About Overcrowding?

“A lot of that can be explained by a sort of positive feedback loop,” explained Casey Wichman, the economist who authored the study. “The parks you’d expect to be popular are also popular online.”

Wichman said some of that popularity is down to certain easily photographed, “aesthetically appealing” locations. Think Glacier Point in Yosemite National Park, with its iconic view of Half Dome. And he says that popularity can also be explained by name recognition.

“It’s like a checklist,” he said. People want to show off to their social media followers the fact that they visited that exciting and popular park.

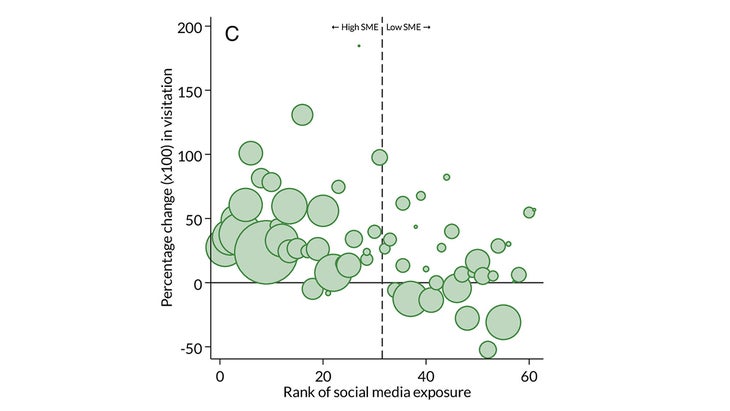

“Parks with greater exposure saw dramatic increases in recreational visitation over the last decade,” wrote Wichman in the study. “On average, parks with greater exposure exhibit 16 to 22 percent increases in recreational visits, whereas parks with weaker exposure exhibit no change, or decreases, in visitation.”

And that’s a problem, not only because the most popular parks and their most well known photo locations are now overrun with selfie seekers, but also because the park service as a whole faces a massive shortfall in its maintenance budget, and the money visitors bring to less popular parks could help those address their own backlogs.

Nationwide, the NPS last tabulated that backlog at $22 billion. The park service’s annual budget, in comparison, is under $3.5 billion. There is no existing plan to close that gap, but in the parks themselves, entrance fees and other money visitors bring can help.

“NPS sites can retain 80 percent of the revenue generated from entrance fees and other recreational fees,” Wichman explained. “Social media has poorly targeted revenue increases to parks that need it most.”

Social media engagement versus changes in visitation, by park. (Photo: Casey Wichman)

What kind of social media exposure is effective? Wichman found that it’s not posts made by the parks or their official affiliates themselves, but rather organic content created by visitors, then re-shared by their followers that draws the most eyeballs, and subsequently the most visits.

It comes as no surprise that photos and videos perform better than plain text.

After all, Wichman states in the study, “The notion that shared media influences visitation to National Parks is not new. In 1951, Time Magazine published Ansel Adams’ photographs of Capitol Reef and Yosemite National Park with the following description: “No artist has pictured the magnificence of the western states more eloquently than photographer Ansel Adams. This summer thousands upon thousands of tourists will follow Adam’s well-beaten trail up and down the National Parks fixing the cold eyes of their cameras on the same splendors he has photographed–and hoping, somehow, to match his art.””

Wichman also went to great lengths to control for variables. Could marketing campaigns run by non-profits connected to the parks, or local governments hoping to cash in on tourist dollars impact the results? Wichman created an algorithm that removed data chronologically adjacent to those. He did the same for factors like seasonal weather, and whether or not a park has significant name recognition.

Could Social Media Help Fund Our National Parks?

While Wichman’s study stops short of making any actual policy recommendations to the park service, its affiliated non-profits, or state and local governments, he says some of its takeaways are implicit.

“Think of social media as a form of advertising,” he says. “Peer influence matters when we make consumptive life choices. Encouraging people to share their positive experiences will inspire others to visit.”

How does this phenomenon affect less-visited (and perhaps less-photogenic) parks and monuments? Wichman referenced the Okefenokee Swamp, a National Wildlife Refuge that straddles the Florida-Georgia border (Wichman teaches at Georgia Tech, I was born in Kennesaw).

“It’s just swamp,” he says, but goes on to explain that creating better photo opportunities for visitors, or amplifying their posts, could increase engagement, and with that, visitation and revenue, which could ultimately foster more widespread efforts at ecosystem preservation.

If managers of public land, or the non-profits and state and local governments that often fund marketing campaigns around those lands want to draw visitors to new areas, or distribute them away from only a few popular areas, they simply need to provide the selfie bait necessary.

Degree of popularity on social media versus real world, by park. (Photo: Casey Wichman)

Wichman says he was inspired to to put the study together after reading an Outside article in 2019 about the impacts of social media on recreation in national parks, and on other public lands. In that piece, I detailed the injuries and deaths attributed to social media in those places, along with their subsequent costs, while arguing that social media still created a net positive for national parks and other public lands.

“I wondered how much I could explain with data,” said Wichman, of the study’s genesis.

Wichman told me that he chose national parks as the subject for the simple reason that that NPS tracks and publishes a lot more data than the United States Forest Service, Bureau of Land Management, or state agencies do. Most visitors to most national parks enter through gates and interact with services while there. That’s not necessarily the case elsewhere, but Wichman says his findings can be extrapolated to other forms of public lands.

The economist also explains that there are lessons to be learned from what’s not in the study. While parks provide an easily checked box for tourists at popular national parks and iconic views, other forms of public land are, by their nature, less likely to foster social media engagement. That may be an argument for skipping a geotag on your next outdoor selfie, or choosing to add one could be a best practice for tourist boards, or state or local governments hoping to increase revenue from visitors.

Wichman sees benefits with the latter practice—a perspective that I share. Public lands are, he said, an “iconic public good that we all have access to.” And, “The more people we can get to visit these places, the better.”

No comments:

Post a Comment