What stands out that Sweden did as well as all those other folks who went crazy trying to conterol outcomes.

I do think that the virus spread much faster and further than anyone understoodk, but also diminished far sooner as well. We were all exposed sooner or later and most just shook it off.

I do think I encountered it twice and my practise of vitimin C saturation forced it to remain eternal while it lingered in external tissues slowly driving my immunity up. Or not at all.

No masks, no lockdowns: how did that work out for Sweden?

When the pandemic hit and lockdowns began around the world, Sweden went its own way – and became a control group in a vast experiment. Two years on, the results are clear.

https://steveblizard.substack.com/p/no-masks-no-lockdowns-how-did-that?s=r

Stockholmers enjoying their freedom in April 2020. Picture: Anders Wiklund / TT News Agency via AFP

By Johan Anderberg From The Weekend Australian Magazine March 25, 2022

On Friday, March 6, 2020, three doctors in their sixties arrived at an inconspicuous building near Stockholm in Sweden. It was already late in the afternoon. The first doctor was Jan Albert. He was the leader. Albert was a professor in infectious-disease control at the Karolinska Institute. He was the one who had set up the meeting. The second was Johan von Schreeb. He was the celebrity. Von Schreeb was a storm chaser who would get on a plane as soon as disaster struck anywhere in the world. Way back in 1993, he had founded the Swedish section of Doctors Without Borders; in 2014, he had been named “Swede of the Year” by the news and current affairs magazine Fokus. The third was Denis Coulombier. He was the Frenchman. Until the year before, Coulombier had been head of the preparedness and response unit at the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, headquartered in Sweden. Now he was retired, but remained an authority.\

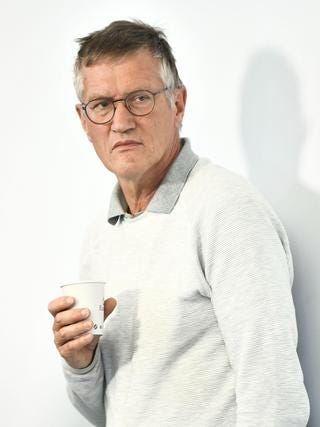

Anders Tegnell. Picture: Claudio Bresciani

As they waited inside the offices of the Swedish Public Health Agency, the sky was darkening. Finally, Anders Tegnell, Sweden’s state epidemiologist, came to meet them. Albert was the first to speak: “There is an opportunity to act now.” Six days earlier, the February school break had ended in Stockholm. Many of those who had returned from Italy and Austria had brought back an infection. They were carrying SARS-CoV-2 – a virus originating in China that gave rise to a mysterious pneumonia-like illness.

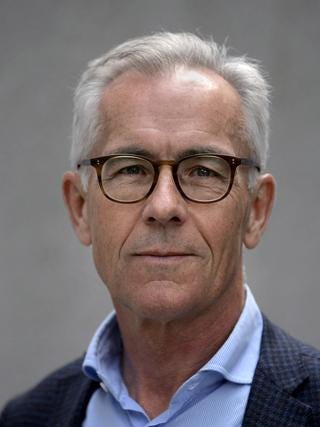

Denis Coulombier. Picture: Olivier Morin/AFP

Albert had helped Region Stockholm forecast the spread of the virus, and what he saw worried him. He told Tegnell about two studies he’d read that seemed to indicate that children could spread the disease even if they weren’t exhibiting symptoms. In Spain and Italy, the rate at which the infection spread was already exponential. Soon it would be here, too. Von Schreeb recounted conversations he’d had with colleagues in Italy. Of the patients ending up in hospital, more than one in five needed intensive care. Then Coulombier stepped in. If there were plans to introduce measures, now was the time.

Tegnell replied: there was no need. The Frenchman looked at the Swede across the table in astonishment. Tegnell said that, so far, no secondary cases had been identified in Sweden – no individuals who had picked up the virus from someone inside the country. There was no community transmission in Sweden at this point. Coulombier felt a mounting frustration. That was no way to think. When dealing with a completely new virus, you couldn’t ask for perfect data before making decisions. You had to rely on your judgment and the guesses of other experts.

Tegnell’s actions were surprising. In epidemiological circles, he was known as the man who’d mass-vaccinated the entire Swedish population against the swine flu in 2009-10. No other country had vaccinated such a large part of its population. In hindsight, it had turned out to be an over-reaction. The flu was mild and soon forgotten. Instead, hundreds of children and young people suffered from the sleep disorder narcolepsy, which was linked to the vaccine. Now, 11 years later, it appeared that Tegnell was acting in the completely opposite way.

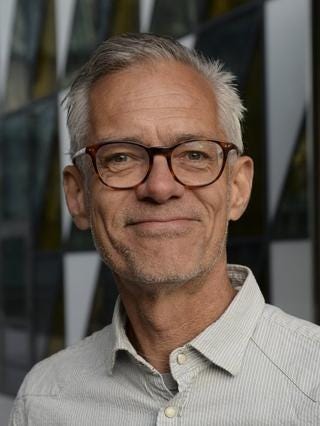

Jan Albert. Picture: Janerik Henrsson / TT News Agency / AFP

Less than a week later, the three doctors who had walked together to the Public Health Agency to warn Tegnell were beginning to drift apart. Gradually, they began to form different opinions about what measures were required to face the looming pandemic. On March 12, Coulombier wrote to Albert and von Schreeb that he hoped “Anders & co” would act swiftly. It was time to close the schools. “History books are watching us,” the Frenchman wrote. But from now on, the Swedes in the group would fall in with Tegnell’s line – which was also theirs. Its main gist was that it was reasonable to make certain simple interventions, but closing down schools – or society, for that matter – would be an over-reaction. What no one foresaw was that the rest of the world was about to side with the Frenchman.

Johan von Schreeb. Picture: Supplied

The path chosen at the time and over the following weeks turned Sweden into a control group for the enormous experiment the world was thrown into. For almost all of 2020 Sweden imposed no curfews, kept compulsory schools open, and didn’t force its citizens to wear face masks. Adjustments made to the strategy from November of that year – lower density limits in restaurants, limits on public gatherings – didn’t succeed in wiping Sweden’s unique path from memory. If anything, the opposite was true. When the Swedish parliament recommended face masks for its members a year into the pandemic, it had the effect of highlighting the fact that for all this time members of parliament had not been masking up. For almost all of 2020, Sweden had chosen a different path. So, how did it go?

It’s no coincidence that the word “viral” has gained new meaning in the digital age. Ideas, thoughts, opinions – they spread the same way, from one person to another, and just as rapidly as the viruses the word originally referred to. During the 2020 pandemic year, one such idea spread from country to country, from politician to politician. From China to Italy and Spain, across the European continent to North America, South America and Africa. It was the idea that countries could close down their societies, and that by forcing people to stay home they could prevent the spread of the virus. It was an idea never before tested at such a scale and for which no one had calculated the social and economic costs.

Throughout 2020 it remained difficult to argue for any other solution than the one so many countries had chosen. Scientists who did so suffered badly: they saw their invitations to conferences withdrawn; their institutions distanced themselves from them. The fact that critics in several cases were censored by large US platform companies was perhaps less significant than the way in which, early on, influential journalistic institutions in the US and Europe chose to equate those who expressed lockdown scepticism with a general contempt for science. In this respect Sweden too was an exception. The debate about what level of restrictions should apply was perhaps louder than in other countries – but it was also freer.

At this stage it was not unreasonable to assume that Sweden would pay a high price for its freedom. In the US, with its forceful lockdowns, the death toll per capita was significantly lower than in Sweden throughout the spring of 2020. And on websites where the ravages of the pandemic could be followed in real time – such as Our World in Data, the Johns Hopkins University database, or Worldometer – it was clear that Sweden had more deaths per capita than most other countries. But the experiment went on.

During the months that followed, the virus continued to ravage the world, and the death toll in several of the countries that had locked down began to surpass Sweden’s one by one. The UK, the US, France, Poland, Portugal, Hungary, Spain, Argentina, Belgium – countries that had shut down playgrounds, forced children to wear face masks, closed schools, fined citizens for hanging out on the beach, and surveilled parks with drones – were all hit harder than Sweden. In Sweden, everyone had retained their legal right to move freely within the country. With a few exceptions, youth sports had been allowed to continue. No Swede had been prohibited from leaving their house. The primary schools had kept operating. Parks and beaches had remained open. No Swede had ever been forced to wear a face mask outside.

When the statistics agency Eurostat measured excess mortality for 2020, Sweden ended up in 22nd place out of 30 European countries. In a report by the UK Office for National Statistics, which adjusted the results for such factors as age structure, Sweden ranked 18th out of 26.

By December 2021, 56 countries had registered more deaths per capita from Covid-19 than Sweden. And when the UK Office for National Statistics updated their figures, it turned out that during the period of just under 18 months between January 2020 and June 2021, Sweden had experienced an excess mortality of minus 2.3 per cent. Together with seven other European countries, including its three Nordic neighbours, Sweden had actually experienced a mortality deficit.

There were other ways to measure the ravages of the pandemic: the prevalence of post-viral syndrome (long Covid); an increased budget deficit; unemployment; and so on. Sweden couldn’t be said to stand out on the basis of these measures either. Yet Sweden had not been spared. For much of 2020, the country’s students in upper secondary school had been denied in-person teaching. At the beginning of 2021, students in years 6 to 9 in several municipalities had been affected, too. But in most respects, Sweden had been saved from the devastation afflicting societies that had shut down.

There never had been a path that guaranteed less death, less suffering, than any other. There only ever were alternatives carrying different risks. As the virus swept through Sweden, new winners and losers were created. A seven-year-old was allowed to go to school and see their friends every day. A 71-year-old was advised to stay home.

The choice that Sweden had made was clear. But it was also unspoken. Long into the pandemic, Johan Giesecke, Sweden’s former head epidemiologist and Tegnell’s old boss, dared to speak about that choice. With every passing day, with every interview he did, his sentences grew plainer and plainer. It was really quite simple: his life, he argued, was less valuable than his grandchildren’s lives. And not just his grandchildren’s. All children’s lives. Their opportunities to get an education, to grow, were more important than reducing the risk of him – now 71 years old – being infected with the virus. The deaths among the country’s elderly – yes, this was a sorrow they’d have to carry with them for a long time. But these were the terms. Every nation had been forced to choose a path. And Sweden had chosen its.

Edited extract from The Herd – How Sweden Chose its Own Path Through the Worst Pandemic in 100 Years, by journalist Johan Anderberg (Scribe, $32.99), out March 29.

An official inquiry into Sweden’s Covid response handed down its final report last month. It concluded that the no-lockdown strategy was fundamentally correct but that tougher measures (limits on public gatherings, temporary closure of high-risk locations, etc) should have been introduced earlier. It noted that many countries that pursued lockdowns “experienced significantly worse outcomes than Sweden, indicating… that it is highly uncertain what effect lockdowns have in fact had”. The panel of eight experts noted high death rates among the elderly and said measures to protect them had failed. It also criticised the government for delegating too much responsibility to the Health Agency. More than 17,000 people have died from or with Covid-19 in Sweden – higher than its Nordic neighbours. “After two years of pandemic, Sweden does not stand out,” Anders Tegnell said. “We are not the best, but we are definitely not the worst.”

No comments:

Post a Comment