It is our pleasure to welcome back Madeleine Daines,

author of The Story of Sukurru and Before Babel: The Crystal Tongue, as

our featured author for February.

Madeleine embarks on a quest that weaves and winds its

way towards a greater understanding of the sacred language of Sumer and

in doing so takes the reader on an adventure that unlocks the hidden

doors of an ancient worldwide language, and its mysterious symbols that

do not follow any modern grammatical rules. Madeleine’s important work

in this area helps to piece together the puzzle of this age old language

and takes the reader on a surprising journey of discovery into the

deepest roots of knowledge.

Tradition assures us that mankind spoke it before the building of the Tower of Babel, which caused its distortion and, for most people, led to this sacred dialect being completely lost to memory.¹

In 2015, I began a re-translation of the oldest literary text in our

possession. Discovered on more than one Mesopotamian clay tablet and

commonly known as THE INSTRUCTIONS OF SHURUPPAK, it was re- baptized THE STORY OF SUKURRU

and published by me under that title in 2017. The two main reasons that

led me to doubt the academic version are straightforward, are

relatively easy to comprehend:

– First, the inconsistencies between two translated Sumerian texts.

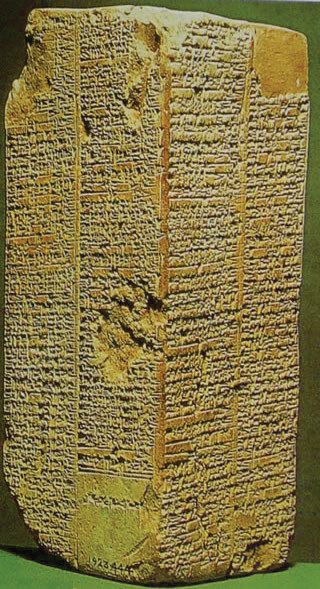

In the well-known SUMERIAN KING LIST, the names and places of kingship

begin in a pre-diluvian age with reigns lasting for impossibly long

periods up to the moment of a great flood. Symbols SU-KUR-RU-KI appear

just before this tragic event on lines 31 and 32, and the resulting

‘Shuruppak/Šuruppag/Sukurru’ was correctly translated as a place name,

identified as such by the suffix KI. The ETCSL version³ of that section

(lines 31 to 39) goes:

(…) and the kingship was taken to Šuruppag. In Šuruppag, Ubara-Tutu became king; he ruled for 18600 years. 1 king; he ruled for 18600 years. In 5 cities 8 kings; they ruled for 241200 years. Then the flood swept over.

But in THE INSTRUCTIONS OF SHURUPPAK, those same symbols, SU-

KUR-RU-KI, became the name of a man, Mr Šuruppag. In fact, the entire

logic of the ‘wisdom’ of THE INSTRUCTIONS OF SHURUPPAK is dependent on

SU-KUR-RU-KI being the name of a man and not that of a city. In complete

contradiction to the translated version of the SUMERIAN KING LIST, this

name appears in lines 6 and 7 of THE INSTRUCTIONS OF SHURUPPAK as the

father; The ETCSL transliteration⁴ gives:

Šuruppag gave instructions to his son; Šuruppag, the son of Ubara-Tutu, gave instructions to his son…

– Second, an easy analysis of the opening symbols, UD-RI-A, which,

through my monosyllabic method, translate to ‘day/sun–collect/gather–

water/flow’. The official translation, considering the language to be

agglutinative, groups them into one and delivers “In those days…”,

leaving to one side all notion of ‘flowing’, ‘water’ or ‘gathering’. I

took the symbols individually and understood that there was indeed an

underlying reference to past times with UD but, with the contrasting MI-

RI-A on the next line, there is also an opposition of UD, the day, with

MI, the darkness of night. Taking the language to be monosyllabic, I

understood those three symbols to mean:

By day, the water flowed and gathered. ⁵

This revelation resulted in a dramatic introduction that completely

contradicted the subject of THE INSTRUCTIONS OF SHURUPPAK: “By day, the

deluge”, the mention of a great flood that decimated the people of

Šuruppag (Shuruppak/Sukurru). And confirmation of the veracity of that

translation came in the SUMERIAN KING LIST where the great flood occurs

on lines 39-40 at a time when the ‘kingship’ is in the city of Šuruppag.

These completely different sets of tablets refer to the same event in

the same place. They even have the same name, Ubara-Tutu, given as ruler

of Šuruppag in one and translated to father of Šuruppag in the other.

Thus, THE STORY OF SUKURRU

is shown to be the correct version from the outset. Contrary to THE

INSTRUCTIONS OF SHURUPPAK, it not only makes sense throughout, but ties

into the timeline, the event, the place and the name of the ruler given

in the SUMERIAN KING LIST.

Despite breakages and some obscure sections, THE STORY OF SUKURRU is a

mine of invaluable information about life in and/or potentially earlier

than 2600 BC Mesopotamia. A few examples:

- Line 45 demonstrates that the sport of (stone) bull-leaping was a rite of passage to adulthood.

- Entertainment in the form of story-telling was accompanied by the music of flutes, with a clear reference to one type; a double flute, the “foreign dadi flute”. ⁶

- The basket was understood as analogy for a sailing vessel, including

the cosmic ship and Noah’s ark. A ritual involving three woven baskets

is mentioned on lines 209-211.

[ a reed vessel was produced using three reed cores. - arclein ]

- Most important of all, it proves that the Great Flood, Noah and his

Ark were already documented ca.2600-2500 BC, several centuries earlier

than any other references. For the pleasure of labouring that point, THE

STORY OF SUKURRU is the first known account of the Flood, pre-dating

all other Mesopotamian mentions.

[ this is excellent news as all the key event is around 12900 BP and successor floods would be notable but also survivable. arclein ]

If THE STORY OF SUKURRU was, as a couple of the pictographic forms

indicate, at least partially copied from one or more considerably

older tablets, then the mind boggles; a relatively complete text of 280

lines, some or all of which dating from the first half of the 3rd

millennium BC…or earlier still?

Although I had hoped, no doubt naively, that the validity and

importance of my translation would be obvious through its own merits,

the similarities with other existing stories, and its presentation as a

bilingual book open to verification of the symbols and my method – it

became evident from subsequent questions that it needed more

explanation. And that is why I decided to write a second book. But it’s

one thing to know where to begin a translation – at the beginning – and

quite another to know how to kick off an explanation of an entire

language, particularly a language that does not follow the laid-down

prescriptive rules of grammar, a language that has been manipulated,

tortured and stripped of its fundamental wisdom over millennia, a

language that has already been explained away by more academically

qualified than me. By the way, for those who might continue to prefer to

ignore the evidence cited above and still dismiss my work on the

grounds of my lack of formal qualifications in the matter, I have just

two questions. Who gave the first experts their first lesson in early

Sumerian grammar and on what authority?

On reflection, I decided to begin BEFORE BABEL THE CRYSTAL TONGUE at

the most obvious point in linguistic history, with an analysis of the

place names of Babel and Babylon through a Sumerian prism. If nothing

more, it serves to explain the basic method of reading Sumerian symbols.

Then, I took a close look at the famous Sumerian character, Enki, again

through an analysis of the symbols that compose his name. From there, I

moved on to Harran, a town in the south of modern-day Turkey and

another name of Sumerian origin. It lies very close to the now famous,

most ancient site of Gobekli Tepe dated to ca. 9600 BC. Gobekli is a

different matter entirely, a disputed place name of Turkish origin, but I

had already found signs of it along with the pagan Sabians of Harran in

the process of translating THE STORY OF SUKURRU. The name Gobekli is

analysed over several sections of my book. From that point, the journey

of explanation and simultaneous discovery wove its way naturally from

Mesopotamia⁷ to Ancient Greece for an encounter with Prometheus and

Talon, and on to Ancient Egypt where Thoth once reigned supreme.

Finally and surprisingly – even to me – the ship of discovery made a

great surge forward in time and landed in medieval France, in a region

known best (most recently through the fictional DA VINCI CODE) for the

mysterious village of Rennes-le-Chateau. Chapter 19 of BEFORE BABEL THE

CRYSTAL TONGUE visits a little-known site nearby where monks, devotees

of Saint Anthony of Egypt, until relatively recent times perpetuated an

age-old tradition of cave-dwelling and where a trace of the Knights

Templars’ passage is still apparent. Although neither the place nor the

timeframe has any superficially evident links to the Sumerian language,

my study of a large stone and the Sator square inscribed on it

demonstrates that some undercurrent, some remnant of extremely ancient

knowledge had been kept alive there. I hasten to add that my account is,

to my knowledge, completely unrelated to any of the existing and

somewhat threadbare theories about the existence of treasure or the tomb

of Jesus in that region of France. It relies entirely on a decoding of

that unique Sator square.

Along the way and again unexpectedly, the great wisdom teacher Hermes

Trismegistus found me and took my hand. Hermes, revered by the Sabians

of Harran (if the 1st millennium AD sources are to be

accepted as true accounts) and assimilated to Egyptian Thoth in deepest

antiquity, was the first alchemist, the Great Magician, Master of all

boundaries. A study of the Sumerian symbols showed me the source of his

name and its hermetic nature, a revelation that, as far as I know, has

not been made public before now. The analysis of it is carried out as

plainly as possible in chapter 18 titled “HERMES AND THE CRYSTAL HERESY”

for reasons that should become obvious in the reading of it. I was led

to a better understanding of the most noteworthy of the magic symbols

and given a few unique glimpses into age-old knowledge which I share on

his authority in this book. I don’t imagine that all has been revealed

but I share what I have so far understood. It is harmless and of

interest.

Over 150 of the earliest Sumerian symbols are mentioned and copied in

BEFORE BABEL THE CRYSTAL TONGUE. Many are discussed in context. Some

(but far from all) of their etymological descendants are also

referenced, most through Greek and Latin words commonly attributed to a

nebulous proto-Indo-European (PIE) source. That is one of the

revelations first mentioned in the notes to THE STORY OF SUKURRU and

confirmed here. We have the means to retrace many of our words to their

origins, a point of immense importance. It signifies that knowledge of

our deepest roots is not entirely lost. Words have been manipulated,

blatantly so in recent times, insidiously turned against the common good

for many millennia. Recovery of our languages’ source, even partial,

must surely go some way to attenuating the dangers foreseen by George

Orwell. We have the means to regain some balance, to look past the many

layers of whitewash and lies.

BEFORE BABEL THE CRYSTAL TONGUE is a language book unlike any other,

where ancient doors creak open on to unexplored avenues. In many of the

words we still use unthinkingly today lies dormant the magic of what was

once a worldwide common language, language of the Matriarch, the sacred

‘dialect’ to which the mysterious Fulcanelli referred, but much more

than just a dialect, the language of the birds, the language of Hermes

Trismegistus, the Crystal Tongue. I have done my best to bring it back

to life. You might find there something I have missed. I hope so.

The full translation of THE STORY OF SUKURRU is given in the annexe.

Notes

¹ Fulcanelli, THE MYSTERY OF THE CATHEDRALS AND THE ESOTERIC INTERPRETATION OF THE HERMETIC SYMBOLS OF THE GRAND WORK,

Introduction, Part III, (1926) published by Jean Schemit, rue

Laffitte, Paris, France. Fulcanelli is a pseudonym, the author’s true

identity unknown.

² This tablet of the Sumerian King List (sourced from Wikipedia) is

in the Ashmolean collection and dates to ca. 1827 BC, Old Babylonian

period.

³ The Sumerian King List, Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature (ETCSL), ref. 2.1.1:

⁴ Classified as ‘Wisdom literature’, The Instructions of Šuruppag,

Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature (ETCSL), ref. 5.6.1: http://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/cgi-bin/etcsl.cgi?text=t.5.6.1#

⁵ Discussed in the article ‘The Rustle of Stones’: https://grahamhancock.com/dainesm1

⁶ Line 102 where DA-DI translate to ‘arm’ and ‘equal’ or ‘divide’.

The context indicated the use of one or more instruments allowing for a

wide tonal range. There exists a Chinese flute called the ‘dadi’.

⁷ For the origin of Greek ‘meso’ (middle), part of the name

Mesopotamia which is understood to mean ‘between the rivers’, see the

Sumero-Hermetic proverb ME ZU NU MU ZU, shown with its source symbols

and several possible translations, on my website: https://madeleinedaines.com/

No comments:

Post a Comment