They went on to show that at higher temperatures and pressures, that Xe combines with iron and Nickle as well. This provides a natural Xenon sink for all planets.

This led to a new understanding of what takes place with the Core.

It has opened up an explanation for the hollow Earth that works with classical physics. This is welcome.

Xenon forms compound at extreme temperature and pressure

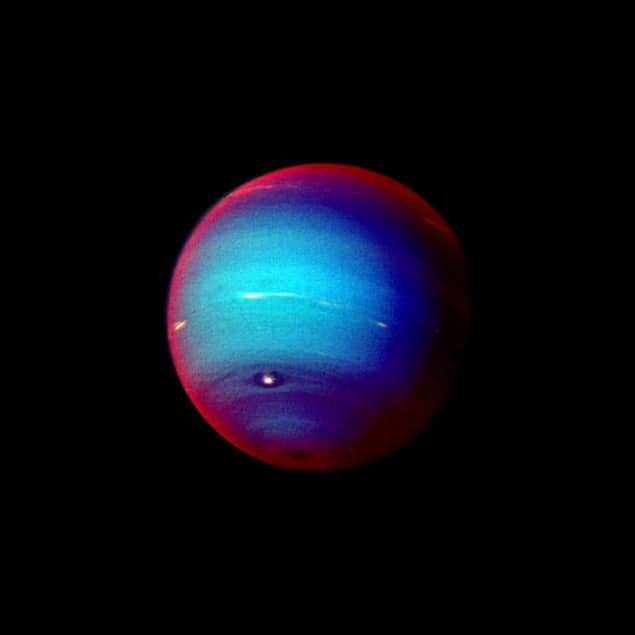

The noble gas xenon reacts with water ice at exceedingly high

temperatures and pressures – conditions that are found within the

interiors of planets such as Uranus and Neptune. That’s the conclusion

of an international team of researchers who used X-ray diffraction and

theoretical calculations to determine the crystal structure of the

resulting compound, which has a Xe4O12H12

primitive cell. The findings take planetary scientists one step closer

to solving the “missing xenon paradox” and could also improve our

understanding of xenon’s isotopes.

In the early 1970s researchers noted the surprising lack of xenon

in Earth’s atmosphere when compared with the concentration of other

noble gases – almost 90% of the expected amount of xenon is missing.

However, xenon is found at the expected abundance elsewhere in the solar

system – on meteorites, for example. This suggests that the

mysteriously missing noble gas is merely hiding somewhere on our planet.

Curiouser and curiouser

A multitude of theories have been purported suggesting that, for

example, xenon might have been ejected into space, or be trapped on

Earth in the polar caps, or stuck in sediments, deep in oceanic trenches

or even within the Earth’s core. But none of the theories could account

for all of the missing gas. Further research has also found that both

Mars and Jupiter seem to have a similar lack of xenon within their

atmospheres.

As a noble gas, xenon is assumed to be non-reactive under normal

conditions. But over the years, researchers have tried to make chemical

compounds containing xenon at extreme pressures and temperatures similar

to those that are found deep within the Earth. In 1997 scientists tried

to react xenon with iron under such conditions, but found that no

compound was formed. In 2005 Chrystele Sanloup of Pierre and Marie Curie

University in Paris, along with colleagues, found that the gas could

displace and then substitute silicon in quartz at high temperatures and

pressures. However, the researchers also noted that the xenon escapes

just as easily from the material. Further work, carried out by another

group, found that xenon could also bond to oxygen within quartz,

allowing the researchers to synthesize xenon dioxide (XeO2) for the first time.

Extreme measures

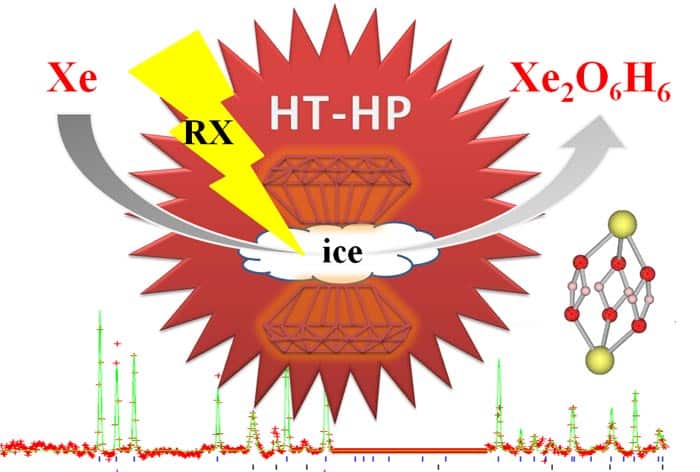

Sanloup (now at the University of Edinburgh) and colleagues in

France, the UK and US have now shown that at pressures above 50 GPa and a

temperature of 1500 K, xenon reacts with water ice to form Xe4O12H12.

Sanloup used a diamond-anvil cell – a device that squeezes a sample

between two tiny, gem-grade diamond crystals. This was laser heated to

create extreme conditions similar to those in the interior of the

“ice-giant” planets Uranus and Neptune. Currently, the atmospheres of

Uranus and Neptune have not yet been probed for their xenon

concentrations.

Sanloup carried out her experiments on the ID27 beam line of the

European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF) in Grenoble, France.

“Once we were above 50 GPa, we could see a reaction systematically

taking place and could see a distinct diffraction pattern that suggested

a new phase [was formed],” she says. Sanloup went on to tell physicsworld.com

that the structure that best describes the new phase is a hexagonal

lattice with four xenon atoms per unit cell. However, there were several

possible distributions of the oxygen atoms.

Atom build-up

Sanloup then roped in Stanimir Bonev from the Lawrence Livermore

National Laboratory in the US to analyse the structure and resolve the

location of the oxygen atoms. It was during this analytical work that

the team found that none of the solutions with only oxygen worked, so

hydrogen was added to “build up” the final Xe4O12H12

structure. “The hydrogen would not have been seen with the X-ray

diffraction as it would react too lightly,” explains Sanloup. “But in

the future we could use Raman spectroscopy to see it or we could use

neutron diffraction instead of X-rays, but for that we would need a much

larger sample,” she says. The team suggests that its newly discovered

compound has a weakly metallic character and could be formed in

superionic ice – a phase of water that is believed to exist at high

pressures and temperatures.

Sanloup explains that solving the mystery of the missing xenon is

crucial because the relative abundances of radioactive xenon isotopes

are widely used by geochemists as a tool to probe major terrestrial

processes, such as when the Earth’s atmosphere formed. Naturally

occurring xenon has eight stable isotopes and more than 40 unstable

isotopes that undergo radioactive decay. Isotope ratios are also used to

study the early history of our solar system, including to model planet

formation. But most of these calculations assume that xenon is mostly

non-reactive. The new findings could alter our knowledge of the xenon

isotopes, which in turn would affect our models of planet formation and

evolution.

No comments:

Post a Comment