This is a delightful story of a young girl finding herself as Lucy on stage. It underlines the cultural importance of Peanuts itself. The whole corpus of work needs to be provided continuously to the mass of school children simply because it is a body of subliminal education that embodies Western civilization.

Understand that its creation was also conscious as well. It even succeeded in been timeless and spoke to adults as well Few comic strips really do that, but those that do also win a long lasting adult audience as well.

All good.

.

The Cartoon Character That Gave a Young Girl Permission to be Herself

Author Lisa Birnbach — one of many contributors to the anthology collection 'The Peanuts Papers' — reflects on a seminal childhood moment when Lucy van Pelt helped a helplessly uncool third-grader be someone she thought she never would and never could.

By Lisa Birnbach Oct 22, 2019

Author Lisa Birnbach — one of many contributors to the anthology collection 'The Peanuts Papers' — reflects on a seminal childhood moment when Lucy van Pelt helped a helplessly uncool third-grader be someone she thought she never would and never could.

By Lisa Birnbach Oct 22, 2019

https://www.shondaland.com/live/family/a29541952/lisa-birnbac-peanuts-essay/

For many of their readers, beloved childhood comics were simply welcomed escapes from the world. Whether tucked in away in our bedrooms or huddled in groups with our friends on the playground, flipping through panel after panel of illustration from the likes of Calvin and Hobbes, The Family Circus, and Garfield was just good-hearted fun. But when it comes to The Peanuts, Charles M. Shultz famed comic that ran from October 2, 1950, to February 13, 2000 and, following the gag-a-day lives of Charlie Brown, Snoopy, Sally Brown, Peppermint Patty, Schroeder, and Linus and Lucy van Pelt also felt a little like looking at ourselves, be we children or not. As such, a new anthology, The Peanuts Papers: Writers and Cartoonists on Charlie Brown, Snoopy & the Gang, and the Meaning of Life, looks back at this cultural phenomenon — and all its humor, poignancy, and sometimes commentary — via a collection of personal essays from illustrators and writers. One such, New York Times best-selling author and humorist Lisa Birnbach, elaborates on her history with the Peanuts in the following abridged essay, "Lucy Can't See," from The Peanuts Paper, reliving the moment Lucy van Pelt allowed a then third-grade Lisa to find something in herself she never knew — and feared would never be — there.

In March 1967 the musical comedy You’re A Good Man, Charlie Brown debuted at Theater 80 in New York’s East Village. It ran for four years before moving to Broadway. In advance of it becoming a staple of local theaters and middle schools all over the world, it was cool. Off-Broadway kind of cool. No longer was Peanuts just that comic strip your dad saved for you from the evening paper. It had earned downtown cred. The original company included, as Charlie Brown, Gary Burghoff, (“Radar” from TV’s M*A*S*H). Bob Balaban as Linus and Reva Rose as Lucy.

That same year, a legally blind third-grader mounted the stage of the auditorium at the Lenox School, a second-tier girls school on that same city’s Upper East Side, to play Lucy in a scene from “The Wonderful World of Peanuts,” a series of skits without music. It was performed once in a dress rehearsal, and then live, the next day, at a school assembly. It was the first time that girl had gone anywhere outside of her bedroom without wearing her eyeglasses. The audience at Lenox was shocked when they figured out who that somewhat-familiar looking girl was — that shy third-grader who normally wore coke-bottle-glasses. It was me.

In the sixties the Peanuts gang was the coed group of friends that seemed accessible yet also unattainable. They were sporty. Even if Charlie Brown struck out or Linus was tagged “it.” They lived in what we called the country. (Their homes were houses, not apartment buildings. They were allowed to walk around their neighborhood without adult supervision.) I lived in the city and had to be accompanied everywhere. The Browns, the Van Pelts, et al., were also thoroughly American. (My father was born in Germany and spoke with an accent.) They accepted one another even if they didn’t always care for one another. They spoke like adults though they lived in small child bodies. Everyone stood out and no one stood out.

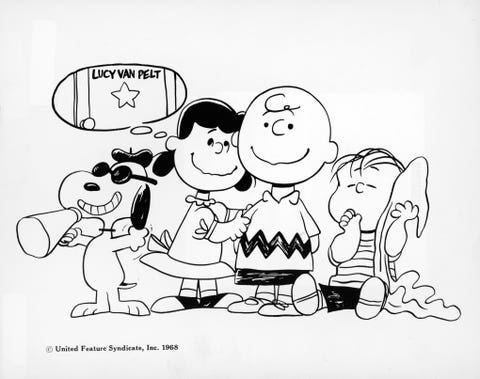

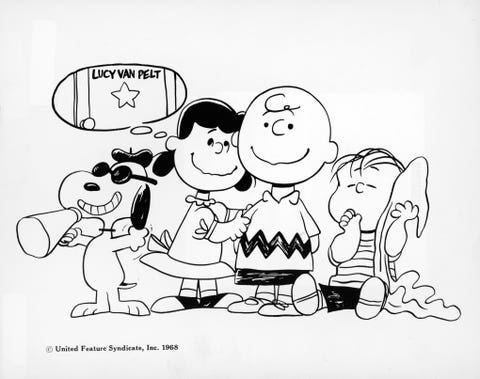

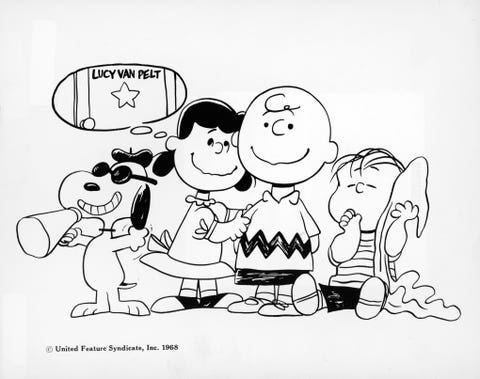

The Peanuts gang

At Lenox, I was the only girl in the Lower School who wore glasses. I was one of the minority who had to wear tie-shoes. Uniforms were required — a winter jumper, a spring jumper, a tunic and bloomers for gym, and even a specific smock for art class. (The French blue painter’s smocks our mothers had to purchase at a store called “Youth at Play.”) We wore them over our other uniforms. This didn’t strike anyone as odd at the time, just the usual rigidity of single-sex schools. Glasses weren’t cool or retro or indicative of braininess or style in the mid-1960s if you were a kid. There were two styles for girls: cats’-eyes and Clark Kent. There were two colors: pale pink and tortoise shell.

In the land of Peanuts, everyone had his or her signature look. (I wouldn’t have called it that in 1967, I realize.) Lucy’s blue dress, Charlie Brown’s yellow-and-black zigzag t-shirt, Schroeder’s striped t-shirt, Linus’ red shirt and blue blankie, Snoopy’s accessories: all provided information about their owners. Our uniforms, on the other hand, only revealed which school we attended. The jumper masked our individual identities in the most efficient way possible. Only through one’s socks and coats did anyone have an opinion, or more likely, did she express her mother’s point of view. Our own stories were less important.

As one of three kids in my family I was instructed never to be selfish. Selfishness was the worst thing I could imagine; if there were anything more despicable, I hadn’t heard of it. I was the only girl in the family so I had less sharing to do if you think about it. I tried not to think about myself too much.

Lucy, on the other hand, reveled in her self-centeredness. It was hard for me to feel empathy towards her. She was dramatic. She wanted Schroeder’s love and respect and had no problem demanding it. She had confidence. She may not have had a guilty bone in her body as she grabbed Charlie Brown’s football away just as his foot was about to kick it. She could be bad. She could be mean. She didn’t really suffer any consequences other than our disdain for her.

Lucy could be bad. She could be mean. She didn’t really suffer any consequences other than our disdain for her.

Lucy not only offered advice, she insisted on being paid for it. (It would take decades — in fact well after Charles Schulz’s death — but eventually Lucy’s big sense of self would be seen as a positive attribute for the modern woman. Was she a little abrasive? Good grief. You can’t worry about making friends while ascending your own ladder to success.)

Unlike what I had experienced, the Peanuts kids did not run off and tell their parents everything. As a pre-pubescent reader of Mr. Schulz’s oeuvre, when I still considered my parents the heroes of my young life, I missed seeing the characters’ parents. True, the gang got called in for supper and were sent to school at a certain hour, but they were independent. They solved their own problems. They got on with things. They didn’t dwell on hurts or resentments, unlike real kids. Unlike real Birnbachs.

Our drama teacher, Mrs. Brandt, decided I would play Lucy to Karen Klingon’s Schroeder. What could she have been thinking?

I was way more Charlie Brown than Lucy. What those tie shoes and glasses didn’t secure, my personality did. Charlie Brown’s proving ground was his pitcher’s mound. Mine was every day: first, the trip in the woody station wagon that was our actual school bus, and then the grind of being at this all girls sanitorium for nine years. I was destined to be unpopular. When your entire grade is made up of girls, most of whom stay for twelve years, no breaks were given. Every gaffe, every embarrassment was remembered, catalogued, and indexed. I couldn’t really move past my reputation. I was so unpopular I wouldn’t have befriended me either. My glasses were Charlie Brown’s zigzag shirt. Most school days someone would ask me if I were blind. I never came up with a snappy rejoinder.

My education as a young girl began at this school in the mid-’60s, but it felt like the ’40’s. (Remember the bloomers we wore for gym? We changed in and out of them in a cloak room.) Most of our teachers, already in late middle age, remembered the Depression and World War II. They had never wed, or were widows or divorcées: interestingly, few of them were parents. Their pride in their students was nominal; many didn’t seem to enjoy kids at all. In those days, a job as a teacher-- especially in a private school--was one of the best a college-educated woman could get, after all. (These were the years before women wore pants in public in the city.) Our teachers wore dresses with stockings and heels. They wore lipstick and had their hair done into the fashionable helmet-like hairdos of the 1950s. Even into the 70’s.

We students curtsied. There were guidelines for that, as well as rules for standing up when an adult came into our classroom. When our headmistress was visible, even out of the most remote corners of our eyes, we were advised to stand up. We recited the Lord’s Prayer several times a week. We received a hands-on lesson on the difference between a ring and a cocktail ring. Many of my classmates had old-fashioned names too. In addition to the requisite Karens, Nancys, and Pattys in my grade, there was a Virginia, a Marion, a Frances, a Mary, and a Marguerite (who told me once she would be my friend but couldn’t be seen with me in the school building. I was overjoyed; that was more than I had gotten from anyone else). I remember an Alma a few years ahead of us and an Eleanor behind us. Our mothers did not work. At least not when we were in Lower School.

I know this doesn’t sound like fun. It wasn’t. My best times were when I could read by myself at home in my bedroom. I read both hungrily and lazily. I read books that were “hard” and I read volume after volume of Peanuts collections. There was no Facebook/Instagram/Snapchat offering photographic proof of other people’s good times; this had to be intuited. When my classmates were, I suspected, seeing one another and having fun together, I listened to 45s over and over on my little record player.

I also enjoyed yelling at my brothers whenever they crossed my threshold.

Get out of my room! Get out of my room!

Wait a second! At home, I was Lucy — bossy and smart. At school I was Charlie Brown — pathetic and ineffectual. Now we’re getting somewhere.

At home, I was Lucy — bossy and smart. At school I was Charlie Brown — pathetic and ineffectual.

Lucy was the warrior queen of the Peanuts tribe. She was feared. She got her way. She seemed untouched by the sickening desire to be popular, a disease that hasn’t exactly gone away. The seven stations on Broadcast television reinforced the urgency of popularity. Every family show pummeled that message home — whether it was learning that the boy who was bullied by the cool kids was actually … kind of cool himself — or when someone’s big sister loaned her little sibling an outfit that made her the hit of the sock-hop.

As one of the taller students in the third grade, I had fully expected to be cast in a male part in “The Wonderful World of Peanuts.” But I was cast as Lucy in the most emotionally challenging scene in the play. The one where Lucy was alone with Schroeder. If I had be one of the three Lucys, couldn’t I be “Therapy 5 cents please” Lucy? Karen and I didn’t have to kiss or anything, but in our little scene Lucy was to declare her love for Schroeder. This, as Karen and I both knew but never spoke of, would result in constant teasing, in perpetuity, for us both. Of the two of us, I had the worse gig, since Karen-as-Schroeder could hunch over her toy piano and ignore me.

We rehearsed. I remember nothing about rehearsals except that I sprawled on the floor, and propped myself up on my elbows, staring into the eyes of Karen/Schroeder. I don’t recall it making anyone laugh. At this point in my character work, I still had every intention of performing my Lucy in my own eyeglasses. As we say now, “the optics” were always a risk, but in the Second Grade Insect Assembly my “Butterfly dancing out of her cocoon” wore glasses, and no one said a word. In our First Grade Christmas Pageant, my Joseph wore small cat’s-eye glasses, and no one complained.

But in the dress rehearsal, less than 24 hours before curtain, Mrs. Brandt surprised me by telling me I wouldn’t be allowed to wear my glasses in performance the next day. I panicked. I was convinced I’d fall off the stage. I pictured it vividly. I’d stumble, I’d roll down the steps. Humiliation was guaranteed.

I couldn’t shake the fear that something awful and embarrassing was my destiny, but I had to commit to becoming Lucy Van Pelt. I practiced without my glasses that night. As life became blurrier, I lost mental focus too. I couldn’t see — or couldn’t see much. From a foot away, life without my glasses has always looked like something seen through a frosted bathroom window: Colorful but formless mosaics, an abstraction.

But the next day, when I stepped on stage, a funny thing happened. Not being able to see Schroeder or her tiny piano freed me from feeling like my boring, unworthy, Charlie Brownish self. Surrounded by my visual fog, I actually felt like someone else. Not me. Not the legally blind, uncool girl who had thrown up (twice) at Lenox; the awkward, bespectacled book-lover who was often the last girl picked for a team; the girl who just wanted someone — anyone — to ask her if she liked The Man from U*N*C*L*E too. All this didn’t matter anymore.

On stage I suddenly felt like an 8-year-old femme fatale, and I turned to the general vicinity of Karen Klingon’s eyes. “Schroeder, look deep into my eyes, and tell me that you love me,” I demanded. Whose voice was that? Whose conviction was that? Had I actually turned into Paula Prentiss? (She was the only actress whose name I knew.) Was that sound the audience laughing? At me or with me?

I didn’t fall.

The crowd cheered.

Reader, my success in “The Wonderful World of Peanuts” didn’t cause my head to swell. I was still asked daily about my blindness, was still reminded about barfing at chorus, and was still chosen last for volleyball. But I did think of my performance as a victory, and an unseeing Lucy led to more roles at Lenox, including an unseeing school girl (unnamed) in “The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie,” and then a legally blind Sancho Panza in “The World of Don Quixote.” (The latter might have been written by the Peanuts playwright.) I knew I’d never be Paula Prentiss. But I also decided that I didn’t have to be Charlie Brown my whole life. I could get contact lenses.

For many of their readers, beloved childhood comics were simply welcomed escapes from the world. Whether tucked in away in our bedrooms or huddled in groups with our friends on the playground, flipping through panel after panel of illustration from the likes of Calvin and Hobbes, The Family Circus, and Garfield was just good-hearted fun. But when it comes to The Peanuts, Charles M. Shultz famed comic that ran from October 2, 1950, to February 13, 2000 and, following the gag-a-day lives of Charlie Brown, Snoopy, Sally Brown, Peppermint Patty, Schroeder, and Linus and Lucy van Pelt also felt a little like looking at ourselves, be we children or not. As such, a new anthology, The Peanuts Papers: Writers and Cartoonists on Charlie Brown, Snoopy & the Gang, and the Meaning of Life, looks back at this cultural phenomenon — and all its humor, poignancy, and sometimes commentary — via a collection of personal essays from illustrators and writers. One such, New York Times best-selling author and humorist Lisa Birnbach, elaborates on her history with the Peanuts in the following abridged essay, "Lucy Can't See," from The Peanuts Paper, reliving the moment Lucy van Pelt allowed a then third-grade Lisa to find something in herself she never knew — and feared would never be — there.

In March 1967 the musical comedy You’re A Good Man, Charlie Brown debuted at Theater 80 in New York’s East Village. It ran for four years before moving to Broadway. In advance of it becoming a staple of local theaters and middle schools all over the world, it was cool. Off-Broadway kind of cool. No longer was Peanuts just that comic strip your dad saved for you from the evening paper. It had earned downtown cred. The original company included, as Charlie Brown, Gary Burghoff, (“Radar” from TV’s M*A*S*H). Bob Balaban as Linus and Reva Rose as Lucy.

That same year, a legally blind third-grader mounted the stage of the auditorium at the Lenox School, a second-tier girls school on that same city’s Upper East Side, to play Lucy in a scene from “The Wonderful World of Peanuts,” a series of skits without music. It was performed once in a dress rehearsal, and then live, the next day, at a school assembly. It was the first time that girl had gone anywhere outside of her bedroom without wearing her eyeglasses. The audience at Lenox was shocked when they figured out who that somewhat-familiar looking girl was — that shy third-grader who normally wore coke-bottle-glasses. It was me.

In the sixties the Peanuts gang was the coed group of friends that seemed accessible yet also unattainable. They were sporty. Even if Charlie Brown struck out or Linus was tagged “it.” They lived in what we called the country. (Their homes were houses, not apartment buildings. They were allowed to walk around their neighborhood without adult supervision.) I lived in the city and had to be accompanied everywhere. The Browns, the Van Pelts, et al., were also thoroughly American. (My father was born in Germany and spoke with an accent.) They accepted one another even if they didn’t always care for one another. They spoke like adults though they lived in small child bodies. Everyone stood out and no one stood out.

The Peanuts gang

At Lenox, I was the only girl in the Lower School who wore glasses. I was one of the minority who had to wear tie-shoes. Uniforms were required — a winter jumper, a spring jumper, a tunic and bloomers for gym, and even a specific smock for art class. (The French blue painter’s smocks our mothers had to purchase at a store called “Youth at Play.”) We wore them over our other uniforms. This didn’t strike anyone as odd at the time, just the usual rigidity of single-sex schools. Glasses weren’t cool or retro or indicative of braininess or style in the mid-1960s if you were a kid. There were two styles for girls: cats’-eyes and Clark Kent. There were two colors: pale pink and tortoise shell.

In the land of Peanuts, everyone had his or her signature look. (I wouldn’t have called it that in 1967, I realize.) Lucy’s blue dress, Charlie Brown’s yellow-and-black zigzag t-shirt, Schroeder’s striped t-shirt, Linus’ red shirt and blue blankie, Snoopy’s accessories: all provided information about their owners. Our uniforms, on the other hand, only revealed which school we attended. The jumper masked our individual identities in the most efficient way possible. Only through one’s socks and coats did anyone have an opinion, or more likely, did she express her mother’s point of view. Our own stories were less important.

As one of three kids in my family I was instructed never to be selfish. Selfishness was the worst thing I could imagine; if there were anything more despicable, I hadn’t heard of it. I was the only girl in the family so I had less sharing to do if you think about it. I tried not to think about myself too much.

Lucy, on the other hand, reveled in her self-centeredness. It was hard for me to feel empathy towards her. She was dramatic. She wanted Schroeder’s love and respect and had no problem demanding it. She had confidence. She may not have had a guilty bone in her body as she grabbed Charlie Brown’s football away just as his foot was about to kick it. She could be bad. She could be mean. She didn’t really suffer any consequences other than our disdain for her.

Lucy could be bad. She could be mean. She didn’t really suffer any consequences other than our disdain for her.

Lucy not only offered advice, she insisted on being paid for it. (It would take decades — in fact well after Charles Schulz’s death — but eventually Lucy’s big sense of self would be seen as a positive attribute for the modern woman. Was she a little abrasive? Good grief. You can’t worry about making friends while ascending your own ladder to success.)

Unlike what I had experienced, the Peanuts kids did not run off and tell their parents everything. As a pre-pubescent reader of Mr. Schulz’s oeuvre, when I still considered my parents the heroes of my young life, I missed seeing the characters’ parents. True, the gang got called in for supper and were sent to school at a certain hour, but they were independent. They solved their own problems. They got on with things. They didn’t dwell on hurts or resentments, unlike real kids. Unlike real Birnbachs.

Our drama teacher, Mrs. Brandt, decided I would play Lucy to Karen Klingon’s Schroeder. What could she have been thinking?

I was way more Charlie Brown than Lucy. What those tie shoes and glasses didn’t secure, my personality did. Charlie Brown’s proving ground was his pitcher’s mound. Mine was every day: first, the trip in the woody station wagon that was our actual school bus, and then the grind of being at this all girls sanitorium for nine years. I was destined to be unpopular. When your entire grade is made up of girls, most of whom stay for twelve years, no breaks were given. Every gaffe, every embarrassment was remembered, catalogued, and indexed. I couldn’t really move past my reputation. I was so unpopular I wouldn’t have befriended me either. My glasses were Charlie Brown’s zigzag shirt. Most school days someone would ask me if I were blind. I never came up with a snappy rejoinder.

My education as a young girl began at this school in the mid-’60s, but it felt like the ’40’s. (Remember the bloomers we wore for gym? We changed in and out of them in a cloak room.) Most of our teachers, already in late middle age, remembered the Depression and World War II. They had never wed, or were widows or divorcées: interestingly, few of them were parents. Their pride in their students was nominal; many didn’t seem to enjoy kids at all. In those days, a job as a teacher-- especially in a private school--was one of the best a college-educated woman could get, after all. (These were the years before women wore pants in public in the city.) Our teachers wore dresses with stockings and heels. They wore lipstick and had their hair done into the fashionable helmet-like hairdos of the 1950s. Even into the 70’s.

We students curtsied. There were guidelines for that, as well as rules for standing up when an adult came into our classroom. When our headmistress was visible, even out of the most remote corners of our eyes, we were advised to stand up. We recited the Lord’s Prayer several times a week. We received a hands-on lesson on the difference between a ring and a cocktail ring. Many of my classmates had old-fashioned names too. In addition to the requisite Karens, Nancys, and Pattys in my grade, there was a Virginia, a Marion, a Frances, a Mary, and a Marguerite (who told me once she would be my friend but couldn’t be seen with me in the school building. I was overjoyed; that was more than I had gotten from anyone else). I remember an Alma a few years ahead of us and an Eleanor behind us. Our mothers did not work. At least not when we were in Lower School.

I know this doesn’t sound like fun. It wasn’t. My best times were when I could read by myself at home in my bedroom. I read both hungrily and lazily. I read books that were “hard” and I read volume after volume of Peanuts collections. There was no Facebook/Instagram/Snapchat offering photographic proof of other people’s good times; this had to be intuited. When my classmates were, I suspected, seeing one another and having fun together, I listened to 45s over and over on my little record player.

I also enjoyed yelling at my brothers whenever they crossed my threshold.

Get out of my room! Get out of my room!

Wait a second! At home, I was Lucy — bossy and smart. At school I was Charlie Brown — pathetic and ineffectual. Now we’re getting somewhere.

At home, I was Lucy — bossy and smart. At school I was Charlie Brown — pathetic and ineffectual.

Lucy was the warrior queen of the Peanuts tribe. She was feared. She got her way. She seemed untouched by the sickening desire to be popular, a disease that hasn’t exactly gone away. The seven stations on Broadcast television reinforced the urgency of popularity. Every family show pummeled that message home — whether it was learning that the boy who was bullied by the cool kids was actually … kind of cool himself — or when someone’s big sister loaned her little sibling an outfit that made her the hit of the sock-hop.

As one of the taller students in the third grade, I had fully expected to be cast in a male part in “The Wonderful World of Peanuts.” But I was cast as Lucy in the most emotionally challenging scene in the play. The one where Lucy was alone with Schroeder. If I had be one of the three Lucys, couldn’t I be “Therapy 5 cents please” Lucy? Karen and I didn’t have to kiss or anything, but in our little scene Lucy was to declare her love for Schroeder. This, as Karen and I both knew but never spoke of, would result in constant teasing, in perpetuity, for us both. Of the two of us, I had the worse gig, since Karen-as-Schroeder could hunch over her toy piano and ignore me.

We rehearsed. I remember nothing about rehearsals except that I sprawled on the floor, and propped myself up on my elbows, staring into the eyes of Karen/Schroeder. I don’t recall it making anyone laugh. At this point in my character work, I still had every intention of performing my Lucy in my own eyeglasses. As we say now, “the optics” were always a risk, but in the Second Grade Insect Assembly my “Butterfly dancing out of her cocoon” wore glasses, and no one said a word. In our First Grade Christmas Pageant, my Joseph wore small cat’s-eye glasses, and no one complained.

But in the dress rehearsal, less than 24 hours before curtain, Mrs. Brandt surprised me by telling me I wouldn’t be allowed to wear my glasses in performance the next day. I panicked. I was convinced I’d fall off the stage. I pictured it vividly. I’d stumble, I’d roll down the steps. Humiliation was guaranteed.

I couldn’t shake the fear that something awful and embarrassing was my destiny, but I had to commit to becoming Lucy Van Pelt. I practiced without my glasses that night. As life became blurrier, I lost mental focus too. I couldn’t see — or couldn’t see much. From a foot away, life without my glasses has always looked like something seen through a frosted bathroom window: Colorful but formless mosaics, an abstraction.

But the next day, when I stepped on stage, a funny thing happened. Not being able to see Schroeder or her tiny piano freed me from feeling like my boring, unworthy, Charlie Brownish self. Surrounded by my visual fog, I actually felt like someone else. Not me. Not the legally blind, uncool girl who had thrown up (twice) at Lenox; the awkward, bespectacled book-lover who was often the last girl picked for a team; the girl who just wanted someone — anyone — to ask her if she liked The Man from U*N*C*L*E too. All this didn’t matter anymore.

On stage I suddenly felt like an 8-year-old femme fatale, and I turned to the general vicinity of Karen Klingon’s eyes. “Schroeder, look deep into my eyes, and tell me that you love me,” I demanded. Whose voice was that? Whose conviction was that? Had I actually turned into Paula Prentiss? (She was the only actress whose name I knew.) Was that sound the audience laughing? At me or with me?

I didn’t fall.

The crowd cheered.

Reader, my success in “The Wonderful World of Peanuts” didn’t cause my head to swell. I was still asked daily about my blindness, was still reminded about barfing at chorus, and was still chosen last for volleyball. But I did think of my performance as a victory, and an unseeing Lucy led to more roles at Lenox, including an unseeing school girl (unnamed) in “The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie,” and then a legally blind Sancho Panza in “The World of Don Quixote.” (The latter might have been written by the Peanuts playwright.) I knew I’d never be Paula Prentiss. But I also decided that I didn’t have to be Charlie Brown my whole life. I could get contact lenses.

No comments:

Post a Comment