I am writing this item because this story is now gaining serious traction. soon enough it will turn into a global panic as well as the real numbers begin to emerge. The general advent of a global urban middle class will be largely universal by 2050. That is not so far away. what that means is a sharply reduced birth rate and that generally means below replacement. Thus the global population should peak at around ten billion folks. For what it happens to be worth, we already produce enough food to feed them all..

The problem is that this will be followed by a natural decline curve that is precipitous. Consider that the worse example will be China which is sertting up to decline from around 1.4 billion to just over 500,000,000 thanks in partucular to their now abandoned one child policy. The global decline is quite capable of quickly dropping say four billion from the rolls before it is possible to change policies able to stem this decline.

Assuming that you have followed me this far and are not dismissing all this out of hand, I want to show us our solutions.

The absolute first aspect that must be addressed is the direct ending of economic poverty itself through the establishment of the formal natural community of 150 souls in combination with sustainable robotic assisted agriculture and communal child rearing. Such a community will demand children as part of its natural economic expression. Even better, it secures the quality of child rearing as a communal effort and objective.

This is not a fantasy as we have many primitive examples to look to such as the Amish in particular. It all has been done forever, but never so consciously.

That will at least stabilize the global economy itself while again increasing the population. we also automatically have the tools available to completely Terraform the Earth itself by making every square mile lived in and sustainably productive. Thus we then have a real target population of 100 billion.

Then there is life extension. That is coming and we are talking about not just extending old age, but about reversing cellular age to the mid thirties. For women that clearly means also plausibly restoring fertility itself. This then provides a viable control in which those wishing to extend their lives can do so by committing to birth several children as well if that is deemed necessary. I certainly can see China wanting to do something like this and with the accepted prospect of a global population of at least 100 billion, many others will want to see this as well.

Folks, this is all going to emerge during the next two generations. Most women alive today could well be offered age reversal in exchange for more children and all that. For all this to function smoothly we do need the rule of twelve itself to also become universal as well. .

.

The Global Fertility Crash

As birthrates fall, countries will be forced to adapt or fall behind.

By Andre Tartar, Hannah Recht, and Yue Qiu

https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/2019-global-fertility-crash/

At least two children per woman—that’s what’s needed to ensure a stable population from generation to generation. In the 1960s, the fertility rate was five live births per woman. By 2017 it had fallen to 2.43, close to that critical threshold.

Population growth is vital for the world economy. It means more workers to build homes and produce goods, more consumers to buy things and spark innovation, and more citizens to pay taxes and attract trade. While the world is expected to add more than 3 billion people by 2100, according to the United Nations, that’ll likely be the high point. Falling fertility rates and aging populations will mean serious challenges that will be felt more acutely in some places than others.

While the global average fertility rate was still above the rate of replacement—technically 2.1 children per woman—in 2017, about half of all countries had already fallen below it, up from 1 in 20 just half a century ago. For places such as the U.S. and parts of Western Europe, which historically are attractive to migrants, loosening immigration policies could make up for low birthrates. In other places, more drastic policy interventions may be called for. Most of the available options place a high burden on women, who’ll be relied upon not only to bear children but also to help fill widening gaps in the workforce.

Each of the following indicators tells a part of the global fertility story: not just how many babies women have on average, but also how well women are integrated into the workforce, what slice of the income pie they receive, and their level of educational attainment. Overall:

Government attempts to manage population growth are nothing new—consider the generous paid maternal leave of the Scandinavian countries or China’s recently rescinded one-child policy, each relatively effective in achieving its stated goal—but a new sense of urgency and even desperation is creeping into the search for ways to reverse the current trends. That said, achieving robust population growth is by no means the only contributor to economic growth—in some countries too-high fertility may actually be a drag on GDP, because of higher costs. But as these indicators suggest, it can be an important tailwind.

To explore these demographic and economic shifts, Bloomberg analyzed fertility data for 200 countries and picked four that were outliers in some respect. Local reporters then interviewed one woman in each place about her economic and cultural forces that shaped her choice to have children—or not.

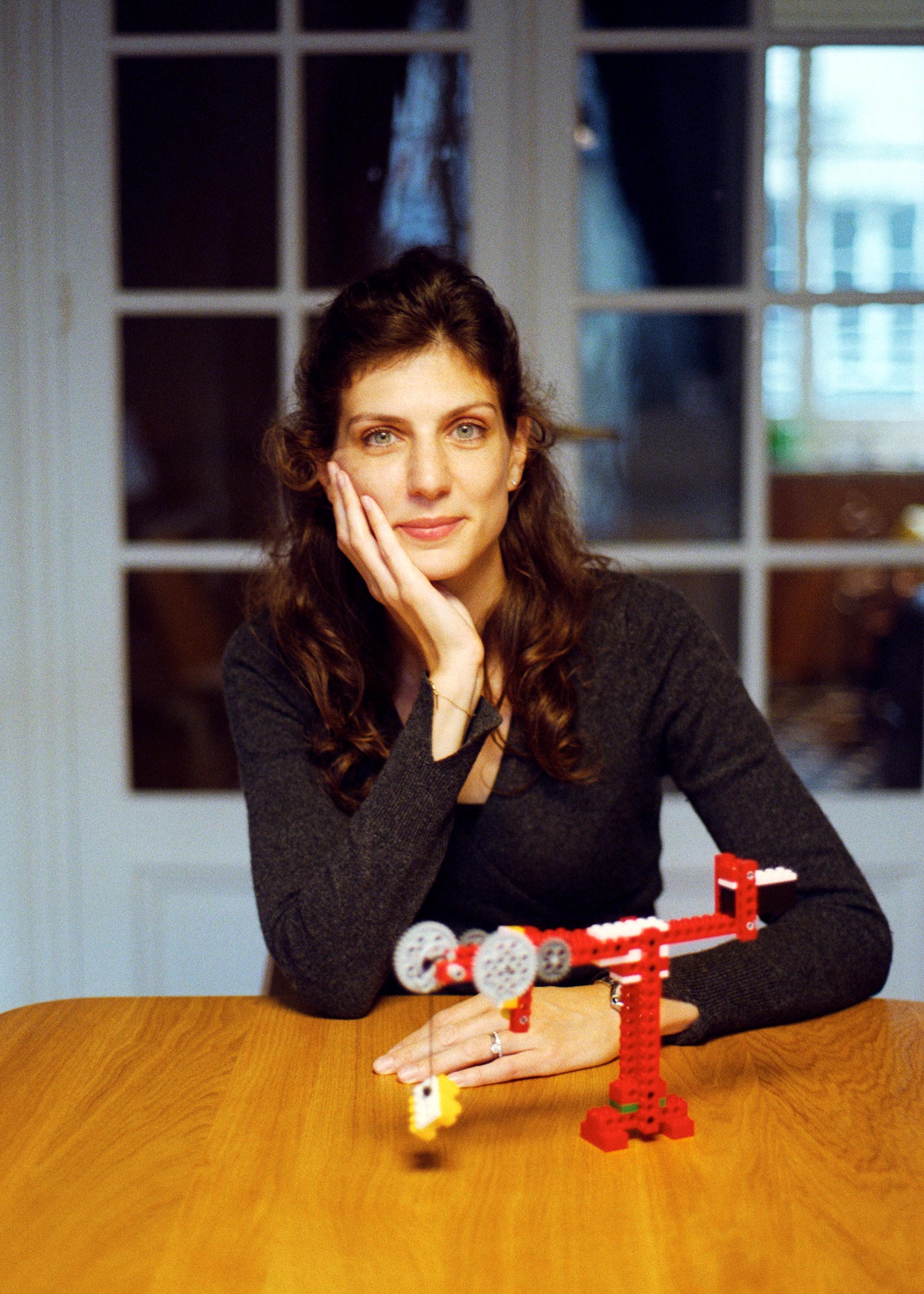

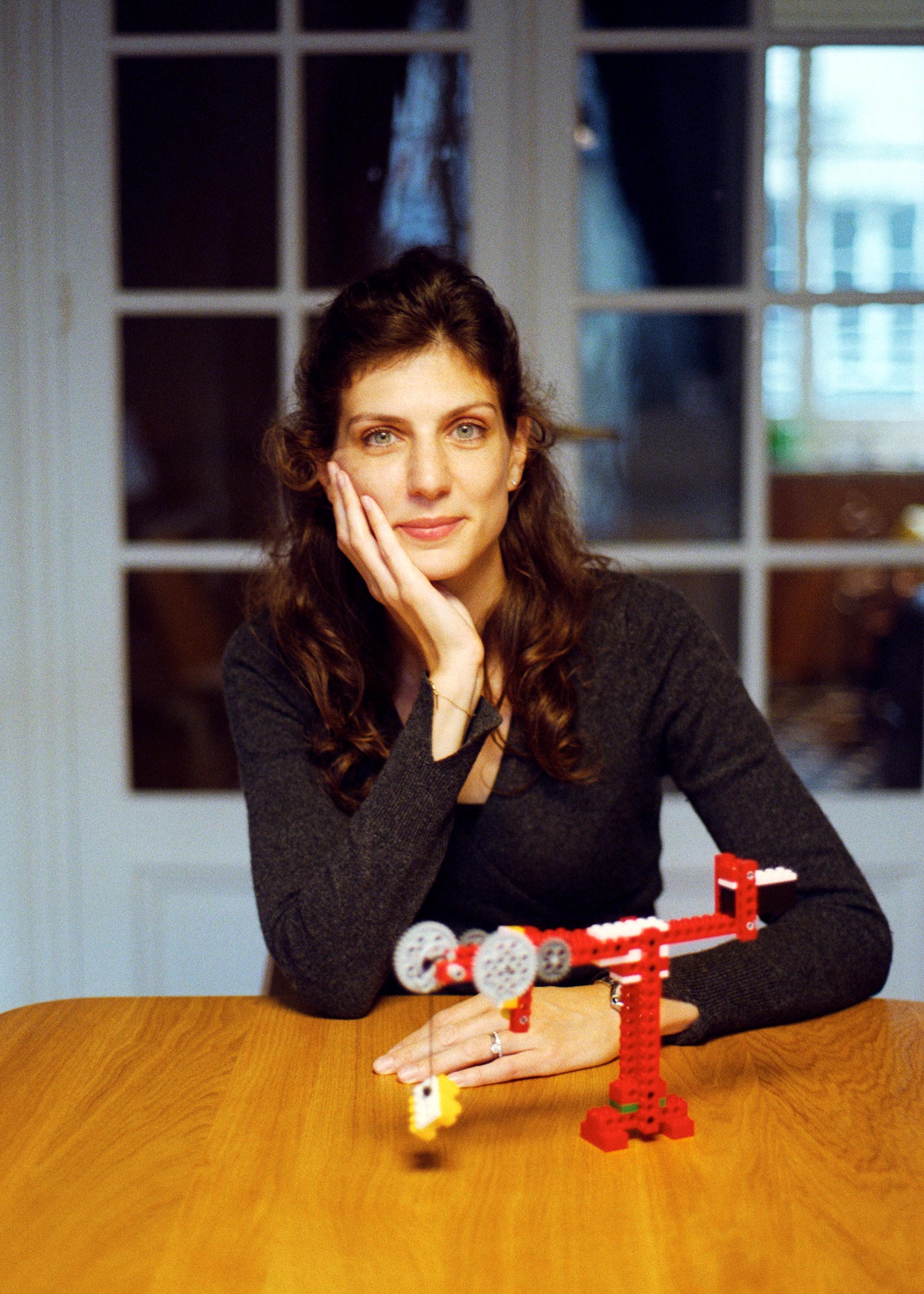

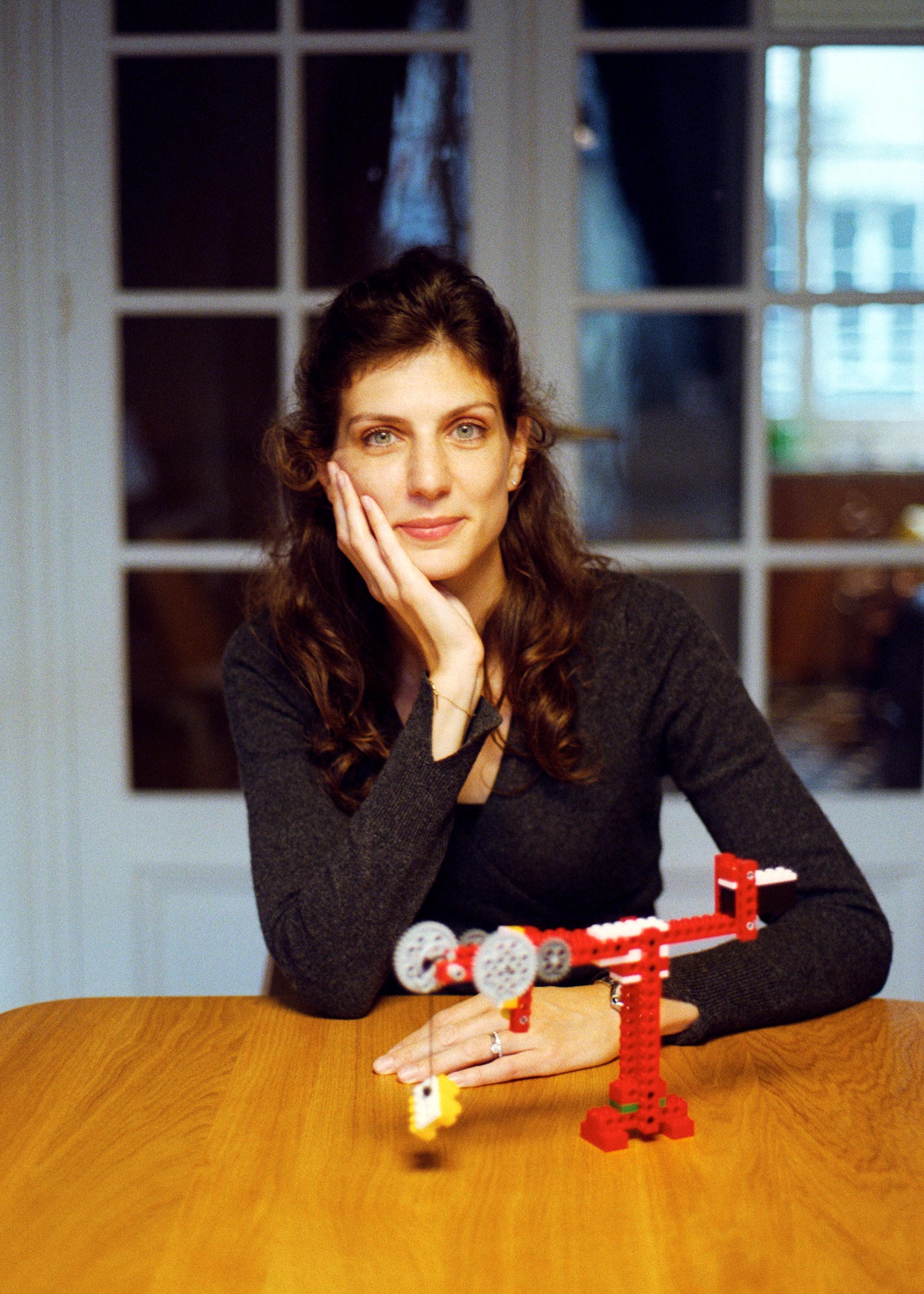

France

Women in France may have won suffrage only in 1945, but they’ve rapidly acquired rights and status. They’re now close to parity with men in income and are highly educated on average. This is due partly to generous benefits such as public day cares, called crèches, that accept babies as young as 3 months.

Celine Grislain works at the Ministry of Health in Paris, where she manages a seven-person team. She and her husband have three children, ages 5, 3, and 1. The older two attend state-run nursery school, while the youngest stays home with a nanny.

“When I became pregnant [with my first child], I had already done a job interview for a new post, so I had to tell my future employer that I’d arrive four months later than planned, but it didn’t set me back. For my second child, I had applied for a post managing a bigger team. I told my employer, but they said that didn’t affect their decision. And for the third, nobody said anything either when I told them.

“Having children forces you to be more efficient. Before having children, I would often stay late in the evenings. I find that when you manage a team, being a boss that doesn’t stay too late removes some pressure from people—it’s a routine that is quite healthy for everyone. After my third child, I went down to 80% [time, working four days a week]. As a civil servant, you have the right to part-time work when you have a child under 3, so 80% is pretty common. People try to adapt, to organize themselves, so that I don’t have too many meetings on Wednesdays [my day off], and I make an effort to compensate. I don’t hesitate to work in the evenings, I don’t hesitate to look at my emails on a Wednesday. I think everyone tries to make an effort, and that’s why it works.

Photograper: Elsa & Johanna for Bloomberg Businessweek

“With our first child, we didn’t get a place in a nursery, but we had friends who were moving so [they] didn’t need their nanny anymore. We have kept her ever since because we’ve become very close. I get a small amount of financial support for working at 80%—it’s not much, around €140 ($155) a month. There are family benefits, but they change depending on your income, and I don’t get much. There is what we call a supplement for child care, and there’s also a tax credit that helped us a lot when we were sharing a nanny. But the credit is capped, and having a nanny to ourselves makes for a big extra cost.

“It’s mainly me that does the shopping, the doctor appointments, but I’ve also got a husband who knows how to cook. I think I do a little more than him, but he does more than my dad did, and he did more than my granddad, so there’s been an improvement with each generation. And my husband supports me with my career. That counts for a lot.” —Interviewed by William Horobin, translated from French

Saudi Arabia

Women in the culturally restrictive oil-rich kingdom have among the world’s lowest rates of labor force participation and wield little economic power. As the country has gotten richer, a phenomenon that tends to lead to longer life expectancies and smaller families, the fertility rate has dipped down close to the rate of replacement.

Lubna Alkhaldi, 34, is a fashion designer and an anchor at her local TV station in Dammam, in Saudi Arabia’s Eastern Province. She’s single and makes $102,400 a year.

“In other societies, husbands may take on roles that help the wife not be a full-time [caretaker], like helping out when she’s out at work. I don’t want to be unfair to everyone—there may be exceptions—but in general it’s not the case [in Saudi Arabia].

“I am not married. It’s not an easy decision to take, not at all. Motherhood is a beautiful thing. I have moments where I wish I had a baby I could hold and play with. But I want to make and build my own family, under my conditions. I wanted to choose my husband myself, out of love. When I was at an appropriate age for marriage, this option was not available. Sometimes people said things like ‘Lubna is not beautiful enough, which is why she’s saying no,’ or ‘She’s not good enough, and she says no so she won’t be embarrassed.’

“I have a B.A. in nutrition, but I didn’t like that field. I wanted to major in media, but my dad refused to let me travel abroad to study—there were no universities here that offered that specialization at the time. I own my house, a villa. I was among the first women to drive; I bought my own car. I live alone. My neighbors don’t interfere in what I do—still, I don’t make it obvious I am alone.

Photographer: Tasneem Alsultan for Bloomberg Businessweek

“My immediate family, my mom and my four sisters, are very proud of me and very supportive. But I get calls sometimes from people who are not happy. They tell me, for instance, to cover my face. My face is my identity. I did one program once for Saudi TV on women and the economy. Now I have a program on social issues. Today, I’m filming an episode on customs and traditions.

“I work long hours every day, including today, Saturday. I am very proud of the decisions I have taken. I am very happy with myself. In our Saudi society, I am no longer at a suitable age for marriage, but I don’t consider age as an impediment. I know that when I find the right man we will accept each other, no matter what the challenges and defects—if you consider age a defect—are.” —Interviewed by Donna Abu-Nasr, translated from Arabic

China

Decades of limits on family size and a culture of women working have led to a steep decline in China’s fertility rate. A recent crackdown on gender discrimination forbids employers from asking female applicants’ marital or maternity status, a step toward keeping women in jobs as the population ages.

Summer Guan, 36, works for a state-owned company in Beijing, where she makes about $34,000 a year. She and her husband have one child.

“I was 34 years old, working for a startup tech company as the head of the marketing team, when I found out I was pregnant. It came to me as a surprise, and my first thought was: What about my job?

“Before the baby, I was a typical career woman: working late hours, leading a team, tackling difficult issues, and always delivering at work. Shortly after leaving the doctor, I sent a group message to the company’s CEO and vice president, who are both female, telling them honestly about this. They congratulated me, but just one day later the CEO told me to go on a business trip for several days. I raised the concern that my physical condition may not be fit for traveling long hours, but the CEO said, ‘Overcome it.’

“The first day back from the trip, I found the company put out a recruitment notice online with the same title and job description as mine. My health was unstable during my pregnancy, so I applied for sick leave. The company agreed, but then the human resources supervisor asked me to submit previous medical records for sick leaves, including those that I already took. I didn’t keep the records, as that was the first time they brought up such demands. Days later they sent an email informing me they would suspend my salary because I failed to provide the required documents.

“By that time, I was roughly three months pregnant. It was so hard to believe a company that I worked so diligently for would treat me this way, so I filed an arbitration suit seeking compensation for my overtime work since joining the company. Right after that, the company shut me out, suspending my work email and removing me from a work communication group, but they never dismissed me officially. By the time I wanted to quit the job, human resources refused to proceed unless I agreed not to ‘claim any fees or hurt the company’s reputation.’ I refused, so they wouldn’t let me take my belongings and refused to issue a resignation certificate, a required document in China’s job market.

“I became one of the first people to act on [China’s new anti-employment discrimination measures] and filed a lawsuit against my previous company. I see women are helpless when facing workplace discrimination. With the new [rules], women’s rights can be upheld. It also sent a signal to the companies not to infringe female employees’ rights.

“The whole incident has taken a toll on my personal life. I was a confident career woman, and financially independent, too. But now my confidence has been chipped away. I suffered from postpartum depression, and sometimes I woke up in the middle of the night crying. I blame myself for not taking good care of my child, and the regret will accompany me for my entire life.” —Interviewed by Bloomberg News, translated from Mandarin

Nigeria

With their high fertility rates, Nigeria and its sub-Saharan neighbors are expected to contribute much of the world’s net population gain over the coming decades. Feeding, educating, and employing these growing numbers will be difficult, and a gender and equal opportunity bill has been stalled in the Nigerian senate since it was introduced in 2010.

Abosede George-Ogan, 36, lives in Lagos, where she has a director-level role at the Lagos State Employment Trust Fund. She and her husband have three children: a 4-year-old girl and 2-year-old twins, a boy and a girl. George-Ogan’s annual salary is about $27,700.

“My dad was in the air force, my mom was a teacher. As a matter of fact, my mom didn’t just work, she had every type of business you can [have]. Apart from her day job, my mom sold ice blocks in the house. She sold popcorn, she had a salon, she had a garment-making fashion design place. She had a computer business at some point. She used to travel to China, Dubai, Senegal to buy stuff. Of course, Daddy works, because he wears a uniform every day and he goes out. But I remember thinking, Oh my gosh, mommy must be so rich, because she does all of these things. She’s selling that or selling this, you know?

“I got married at 31. I graduated university at 20, so for 11 years, somebody was asking every day, ‘What is going on?’ Something must be wrong if you’re not married at a certain age, you know? People worry about fertility—‘the clock is ticking’ is a popular term that you hear around here—and there’s the economic side to it. People feel, especially if you’re focused on your career and you’re thriving, are you going to buy yourself the house and the car and the, you know, lifestyle? What will your husband do? My mom got married young, and I definitely think it was her expectation for her girls.

Photographer: Adriane Ohanesian for Bloomberg Businessweek

“You would definitely have low moments. It gets to a point where, for example, if you were a person who used to go to the club, you don’t fit in there anymore. And then you start to say, Where do I fit in? Where am I going to meet this person? Should I be going outside of my normal comfort zone?

“By the time I got married, it was my decision. Yes, I was conscious of the fact that I was getting older, but it wasn’t as a result of pressure or urgency. I always wanted to have kids, no question. To be honest, now I wouldn’t change anything. Maybe the days where I felt like, Really, why am I not married? I feel like there is some good in getting married a little later—what our society calls late—because you are very clear about what marriage is. I feel like really and truly, if you were single for 10 years, you could accelerate your career to a point where when you got married, there’s no stopping you anymore.” —Interviewed by Tope Alake

The Big Picture

Population dynamics can’t be ignored, but they’re also not economic destiny.

A study last year by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development found that, for most major economies, rising productivity was a more important driver of gross domestic product growth between 2000 and 2017 on average than population growth or change in the employment rate. More than 90% of China’s potential growth in 2017 came from productivity increases, the most of any country and a few rungs ahead of the U.S. For Saudi Arabia, however, 62% came from population growth alone—and Nigeria is even more reliant than the Arab kingdom on the sheer size of its potential labor and consumer pool. France stands out for balancing increased productivity and population with higher employment, likely boosted by a healthy influx of working-age immigrants and its generous labor benefits.

Population is just one of three factors influencing national economies.

Productivity gains can make up some of the gaps as populations taper off and begin to shrink, but it's a much more challenging way to grow an economy and may not be sustainable over time: For most of the countries in the OECD’s study, the relative contribution of productivity to growth has fallen over time.

Ultimately, no country will be left untouched by demographic decline. Governments will have to think creatively about ways to manage population, whether through state-sponsored benefits or family-planning edicts or discrimination protections, or else find their own path to sustainable economic growth with ever fewer native-born workers, consumers, and entrepreneurs.

Editor: Jillian Goodman

Design Direction: Alexander Shoukas

Sources and methodology:

As birthrates fall, countries will be forced to adapt or fall behind.

By Andre Tartar, Hannah Recht, and Yue Qiu

https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/2019-global-fertility-crash/

At least two children per woman—that’s what’s needed to ensure a stable population from generation to generation. In the 1960s, the fertility rate was five live births per woman. By 2017 it had fallen to 2.43, close to that critical threshold.

Population growth is vital for the world economy. It means more workers to build homes and produce goods, more consumers to buy things and spark innovation, and more citizens to pay taxes and attract trade. While the world is expected to add more than 3 billion people by 2100, according to the United Nations, that’ll likely be the high point. Falling fertility rates and aging populations will mean serious challenges that will be felt more acutely in some places than others.

While the global average fertility rate was still above the rate of replacement—technically 2.1 children per woman—in 2017, about half of all countries had already fallen below it, up from 1 in 20 just half a century ago. For places such as the U.S. and parts of Western Europe, which historically are attractive to migrants, loosening immigration policies could make up for low birthrates. In other places, more drastic policy interventions may be called for. Most of the available options place a high burden on women, who’ll be relied upon not only to bear children but also to help fill widening gaps in the workforce.

Each of the following indicators tells a part of the global fertility story: not just how many babies women have on average, but also how well women are integrated into the workforce, what slice of the income pie they receive, and their level of educational attainment. Overall:

Government attempts to manage population growth are nothing new—consider the generous paid maternal leave of the Scandinavian countries or China’s recently rescinded one-child policy, each relatively effective in achieving its stated goal—but a new sense of urgency and even desperation is creeping into the search for ways to reverse the current trends. That said, achieving robust population growth is by no means the only contributor to economic growth—in some countries too-high fertility may actually be a drag on GDP, because of higher costs. But as these indicators suggest, it can be an important tailwind.

To explore these demographic and economic shifts, Bloomberg analyzed fertility data for 200 countries and picked four that were outliers in some respect. Local reporters then interviewed one woman in each place about her economic and cultural forces that shaped her choice to have children—or not.

France

Women in France may have won suffrage only in 1945, but they’ve rapidly acquired rights and status. They’re now close to parity with men in income and are highly educated on average. This is due partly to generous benefits such as public day cares, called crèches, that accept babies as young as 3 months.

Celine Grislain works at the Ministry of Health in Paris, where she manages a seven-person team. She and her husband have three children, ages 5, 3, and 1. The older two attend state-run nursery school, while the youngest stays home with a nanny.

“When I became pregnant [with my first child], I had already done a job interview for a new post, so I had to tell my future employer that I’d arrive four months later than planned, but it didn’t set me back. For my second child, I had applied for a post managing a bigger team. I told my employer, but they said that didn’t affect their decision. And for the third, nobody said anything either when I told them.

“Having children forces you to be more efficient. Before having children, I would often stay late in the evenings. I find that when you manage a team, being a boss that doesn’t stay too late removes some pressure from people—it’s a routine that is quite healthy for everyone. After my third child, I went down to 80% [time, working four days a week]. As a civil servant, you have the right to part-time work when you have a child under 3, so 80% is pretty common. People try to adapt, to organize themselves, so that I don’t have too many meetings on Wednesdays [my day off], and I make an effort to compensate. I don’t hesitate to work in the evenings, I don’t hesitate to look at my emails on a Wednesday. I think everyone tries to make an effort, and that’s why it works.

Photograper: Elsa & Johanna for Bloomberg Businessweek

“With our first child, we didn’t get a place in a nursery, but we had friends who were moving so [they] didn’t need their nanny anymore. We have kept her ever since because we’ve become very close. I get a small amount of financial support for working at 80%—it’s not much, around €140 ($155) a month. There are family benefits, but they change depending on your income, and I don’t get much. There is what we call a supplement for child care, and there’s also a tax credit that helped us a lot when we were sharing a nanny. But the credit is capped, and having a nanny to ourselves makes for a big extra cost.

“It’s mainly me that does the shopping, the doctor appointments, but I’ve also got a husband who knows how to cook. I think I do a little more than him, but he does more than my dad did, and he did more than my granddad, so there’s been an improvement with each generation. And my husband supports me with my career. That counts for a lot.” —Interviewed by William Horobin, translated from French

Saudi Arabia

Women in the culturally restrictive oil-rich kingdom have among the world’s lowest rates of labor force participation and wield little economic power. As the country has gotten richer, a phenomenon that tends to lead to longer life expectancies and smaller families, the fertility rate has dipped down close to the rate of replacement.

Lubna Alkhaldi, 34, is a fashion designer and an anchor at her local TV station in Dammam, in Saudi Arabia’s Eastern Province. She’s single and makes $102,400 a year.

“In other societies, husbands may take on roles that help the wife not be a full-time [caretaker], like helping out when she’s out at work. I don’t want to be unfair to everyone—there may be exceptions—but in general it’s not the case [in Saudi Arabia].

“I am not married. It’s not an easy decision to take, not at all. Motherhood is a beautiful thing. I have moments where I wish I had a baby I could hold and play with. But I want to make and build my own family, under my conditions. I wanted to choose my husband myself, out of love. When I was at an appropriate age for marriage, this option was not available. Sometimes people said things like ‘Lubna is not beautiful enough, which is why she’s saying no,’ or ‘She’s not good enough, and she says no so she won’t be embarrassed.’

“I have a B.A. in nutrition, but I didn’t like that field. I wanted to major in media, but my dad refused to let me travel abroad to study—there were no universities here that offered that specialization at the time. I own my house, a villa. I was among the first women to drive; I bought my own car. I live alone. My neighbors don’t interfere in what I do—still, I don’t make it obvious I am alone.

Photographer: Tasneem Alsultan for Bloomberg Businessweek

“My immediate family, my mom and my four sisters, are very proud of me and very supportive. But I get calls sometimes from people who are not happy. They tell me, for instance, to cover my face. My face is my identity. I did one program once for Saudi TV on women and the economy. Now I have a program on social issues. Today, I’m filming an episode on customs and traditions.

“I work long hours every day, including today, Saturday. I am very proud of the decisions I have taken. I am very happy with myself. In our Saudi society, I am no longer at a suitable age for marriage, but I don’t consider age as an impediment. I know that when I find the right man we will accept each other, no matter what the challenges and defects—if you consider age a defect—are.” —Interviewed by Donna Abu-Nasr, translated from Arabic

China

Decades of limits on family size and a culture of women working have led to a steep decline in China’s fertility rate. A recent crackdown on gender discrimination forbids employers from asking female applicants’ marital or maternity status, a step toward keeping women in jobs as the population ages.

Summer Guan, 36, works for a state-owned company in Beijing, where she makes about $34,000 a year. She and her husband have one child.

“I was 34 years old, working for a startup tech company as the head of the marketing team, when I found out I was pregnant. It came to me as a surprise, and my first thought was: What about my job?

“Before the baby, I was a typical career woman: working late hours, leading a team, tackling difficult issues, and always delivering at work. Shortly after leaving the doctor, I sent a group message to the company’s CEO and vice president, who are both female, telling them honestly about this. They congratulated me, but just one day later the CEO told me to go on a business trip for several days. I raised the concern that my physical condition may not be fit for traveling long hours, but the CEO said, ‘Overcome it.’

“The first day back from the trip, I found the company put out a recruitment notice online with the same title and job description as mine. My health was unstable during my pregnancy, so I applied for sick leave. The company agreed, but then the human resources supervisor asked me to submit previous medical records for sick leaves, including those that I already took. I didn’t keep the records, as that was the first time they brought up such demands. Days later they sent an email informing me they would suspend my salary because I failed to provide the required documents.

“By that time, I was roughly three months pregnant. It was so hard to believe a company that I worked so diligently for would treat me this way, so I filed an arbitration suit seeking compensation for my overtime work since joining the company. Right after that, the company shut me out, suspending my work email and removing me from a work communication group, but they never dismissed me officially. By the time I wanted to quit the job, human resources refused to proceed unless I agreed not to ‘claim any fees or hurt the company’s reputation.’ I refused, so they wouldn’t let me take my belongings and refused to issue a resignation certificate, a required document in China’s job market.

“I became one of the first people to act on [China’s new anti-employment discrimination measures] and filed a lawsuit against my previous company. I see women are helpless when facing workplace discrimination. With the new [rules], women’s rights can be upheld. It also sent a signal to the companies not to infringe female employees’ rights.

“The whole incident has taken a toll on my personal life. I was a confident career woman, and financially independent, too. But now my confidence has been chipped away. I suffered from postpartum depression, and sometimes I woke up in the middle of the night crying. I blame myself for not taking good care of my child, and the regret will accompany me for my entire life.” —Interviewed by Bloomberg News, translated from Mandarin

Nigeria

With their high fertility rates, Nigeria and its sub-Saharan neighbors are expected to contribute much of the world’s net population gain over the coming decades. Feeding, educating, and employing these growing numbers will be difficult, and a gender and equal opportunity bill has been stalled in the Nigerian senate since it was introduced in 2010.

Abosede George-Ogan, 36, lives in Lagos, where she has a director-level role at the Lagos State Employment Trust Fund. She and her husband have three children: a 4-year-old girl and 2-year-old twins, a boy and a girl. George-Ogan’s annual salary is about $27,700.

“My dad was in the air force, my mom was a teacher. As a matter of fact, my mom didn’t just work, she had every type of business you can [have]. Apart from her day job, my mom sold ice blocks in the house. She sold popcorn, she had a salon, she had a garment-making fashion design place. She had a computer business at some point. She used to travel to China, Dubai, Senegal to buy stuff. Of course, Daddy works, because he wears a uniform every day and he goes out. But I remember thinking, Oh my gosh, mommy must be so rich, because she does all of these things. She’s selling that or selling this, you know?

“I got married at 31. I graduated university at 20, so for 11 years, somebody was asking every day, ‘What is going on?’ Something must be wrong if you’re not married at a certain age, you know? People worry about fertility—‘the clock is ticking’ is a popular term that you hear around here—and there’s the economic side to it. People feel, especially if you’re focused on your career and you’re thriving, are you going to buy yourself the house and the car and the, you know, lifestyle? What will your husband do? My mom got married young, and I definitely think it was her expectation for her girls.

Photographer: Adriane Ohanesian for Bloomberg Businessweek

“You would definitely have low moments. It gets to a point where, for example, if you were a person who used to go to the club, you don’t fit in there anymore. And then you start to say, Where do I fit in? Where am I going to meet this person? Should I be going outside of my normal comfort zone?

“By the time I got married, it was my decision. Yes, I was conscious of the fact that I was getting older, but it wasn’t as a result of pressure or urgency. I always wanted to have kids, no question. To be honest, now I wouldn’t change anything. Maybe the days where I felt like, Really, why am I not married? I feel like there is some good in getting married a little later—what our society calls late—because you are very clear about what marriage is. I feel like really and truly, if you were single for 10 years, you could accelerate your career to a point where when you got married, there’s no stopping you anymore.” —Interviewed by Tope Alake

The Big Picture

Population dynamics can’t be ignored, but they’re also not economic destiny.

A study last year by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development found that, for most major economies, rising productivity was a more important driver of gross domestic product growth between 2000 and 2017 on average than population growth or change in the employment rate. More than 90% of China’s potential growth in 2017 came from productivity increases, the most of any country and a few rungs ahead of the U.S. For Saudi Arabia, however, 62% came from population growth alone—and Nigeria is even more reliant than the Arab kingdom on the sheer size of its potential labor and consumer pool. France stands out for balancing increased productivity and population with higher employment, likely boosted by a healthy influx of working-age immigrants and its generous labor benefits.

Population is just one of three factors influencing national economies.

Productivity gains can make up some of the gaps as populations taper off and begin to shrink, but it's a much more challenging way to grow an economy and may not be sustainable over time: For most of the countries in the OECD’s study, the relative contribution of productivity to growth has fallen over time.

Ultimately, no country will be left untouched by demographic decline. Governments will have to think creatively about ways to manage population, whether through state-sponsored benefits or family-planning edicts or discrimination protections, or else find their own path to sustainable economic growth with ever fewer native-born workers, consumers, and entrepreneurs.

Editor: Jillian Goodman

Design Direction: Alexander Shoukas

Sources and methodology:

Below are the individual sources for the various charts in this story.

○ Fertility rate: 2017 data compiled by the World Bank from various sources, including the United Nations, Eurostat, U.S. Census Bureau, the Secretariat of the Pacific Community, and various national statistical offices. Total fertility rate represents the average number of children that women in a given country will have over their lifetimes. The replacement rate is roughly 2.1 children per woman, but may differ slightly based on a country’s mortality rate.

○ Labor force participation rate: 2018 data from the International Labour Organization compiled by the World Bank.

○ Aggregate income ratio: World Economic Forum calculations of 2017 total income earned by women as a share of what men earned, estimated using data on the ratio of working women and men, their relative wages, and overall GDP by country.

○ Literacy rate: 2014 Unesco data compiled by the World Economic Forum.

The four country case studies were identified from among the world’s 25 largest economies—based on the International Monetary Fund’s purchasing power parity (PPP) measure of 2017 GDP—after reviewing the above four indicators, plus available data on educational attainment, wage equality, and statutory protections, including paid maternity leave and post-maternity job guarantees.

The OECD provided Bloomberg with its analysis of the contributions to GDP growth for 18 economies, including three of the case studies in this story: China, France, and Saudi Arabia. Respective contributions for Nigeria were calculated based on instructions provided by OECD, using the latest available data on real GDP, total employment and working-age population.

No comments:

Post a Comment