This is worth noting because it tells us what is actually possible and though rare, it informs of what we need to prepare for. These are killing conditions and today we do have access to air conditioning which will also need to shared if needed.

As with Earthquake response, it is useful to think through what you need to do. For most this is really no problem but it also tells us that those conditions will force us to abandoning much of what we normally are doing in order to seek protection.

The surprise here is the actual number of accidental deaths. these were all folks who thought it was under control. It can go from dangerous to extremely dangerous quickly just like a thunderstorm.

The Deadly 1911 Heat Wave That Drove People Insane

Natasha Frost

https://www.history.com/news/heat-wave-1911-weather-insane

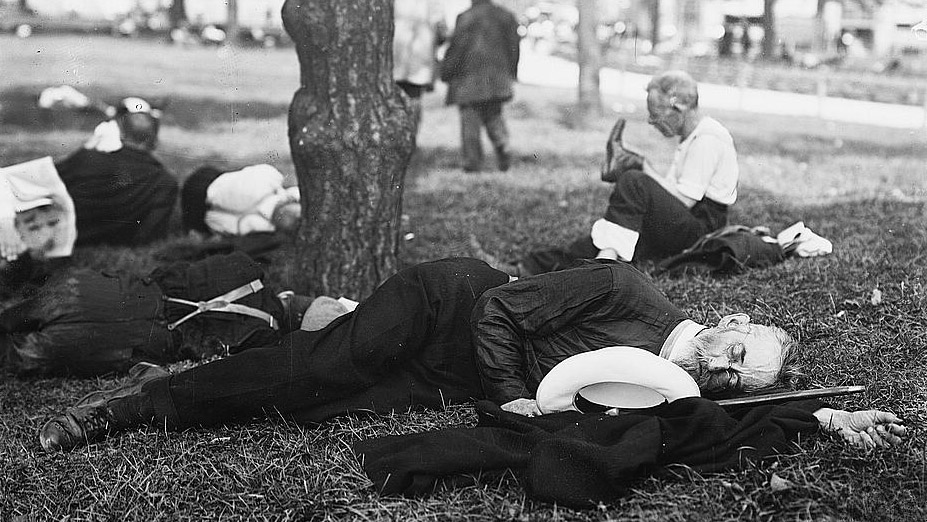

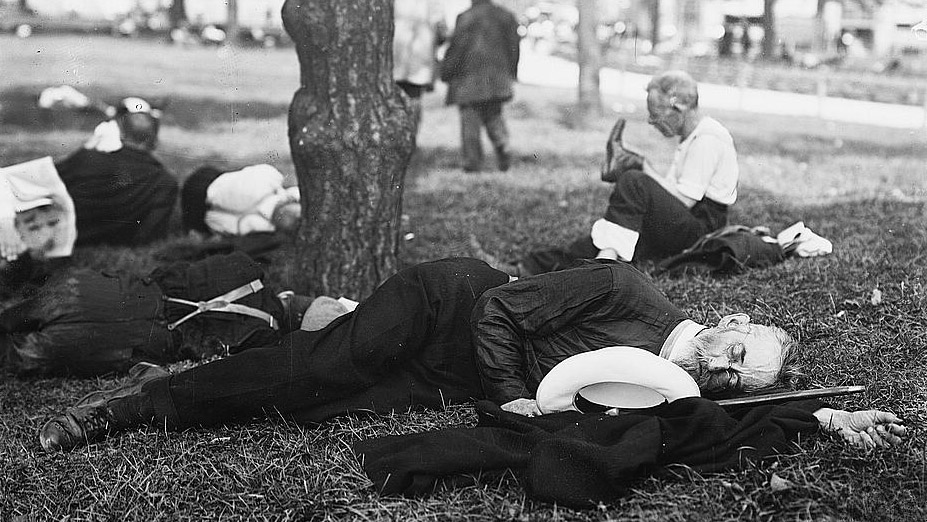

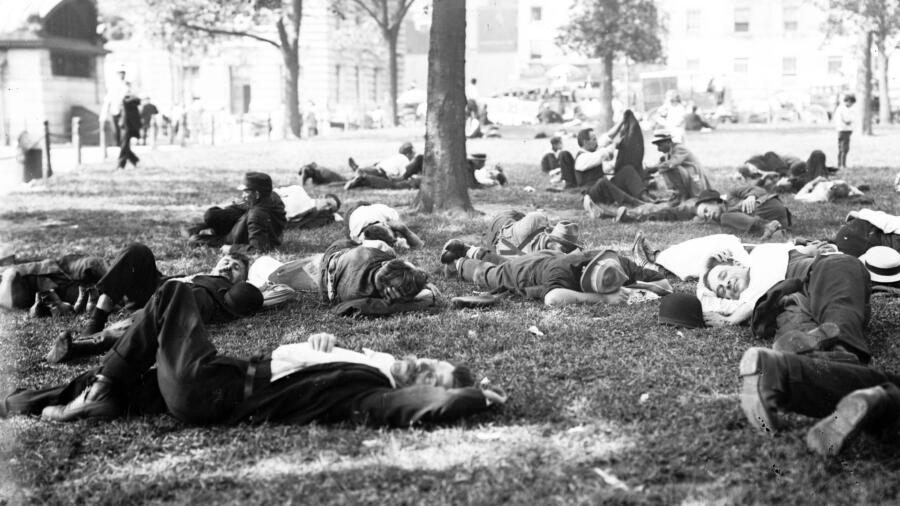

With no air conditioning, resting under the shade of a tree, like here in Battery Park, was much more desirable than crammed indoor spaces during the 1911 heat wave. (Credit: Bain News Service/The Library of Congress)

In July 1911, along the East Coast of the United States, temperatures climbed into the 90s and stayed there for days and days, killing 211 people in New York alone. At the end of Pike Street, in Lower Manhattan, a young man leapt off a pier and into the water, after hours of trying to nap in a shady corner. As he jumped, he called: “I can’t stand this any longer.” Meanwhile, up in Harlem, an overheated laborer attempted to throw himself in front of a train, and had to be wrestled into a straitjacket by police.

In an age before air conditioning or widespread use of electric fans, many struggled to cope with this multi-day deadly heat. June had been easy enough, but a sweep of hot, dry air from the southern plains suppressed any relief from the ocean breeze. In Providence, Rhode Island, temperatures rose 11 degrees in a single half hour. New York City and Philadelphia became sweltering centers of chaos, while all across New England, railway tracks buckled, mail service was suspended and people perished beneath the sun. Total death tolls are estimated to have topped 2000 in just a few weeks.

Though temperatures never quite broke 100 degrees in the first two weeks of July in New York, the city was poorly equipped to handle the heat, and the humidity that went with it. Poor ventilation and cramped living spaces exacerbated the problem, ultimately leading to the deaths of old and young alike, with children as small as two weeks old becoming overcome by the heat.

A man resting under the shade of a tree in Battery Park, 1911. (Credit: Bain News Service/The Library of Congress)

In the peaks of the wave, people abandoned their apartments for the cool grass of New York’s public spaces, napping beneath trees in Central Park or seeking shade in Battery Park. In Boston, 5,000 people chose to spend the night on Boston Common rather than risk suffocation in their own homes. Babies wailed through the night—or failed to wake up at all.

The streets were anarchic: People reportedly ran mad in the heat (one drunken fool, described by the New York Tribune as “partly crazed by the heat,” attacked a policeman with a meat cleaver), while horses collapsed and were left to rot by the side of the road.

Around July 7, when temperatures returned to ordinary levels of July sweat, the humidity remained high. It was this, reported the New York Times, that was responsible for so many of the casualties, “catching its victims in an exhausted state and killing all of them within the hours between 7 and 10 a.m.” The New York Tribune phrased it still more dramatically: “The monstrous devil that had pressed New York under his burning thumb for five days could not go without one last curse, and when the temperature dropped called humidity to its aid.”

Children licking blocks of ice to keep cool during the heat wave. (Credit: Bain News Service/The Library of Congress)

Outside of New York, however, temperatures had climbed higher still. In Boston, people struggled in 104 degree heat; in Bangor, Maine and Nashua, New Hampshire, it reached a record-breaking 106. In Woodbury, New York, a farmer left his field when the outside temperature hit 140 degrees—hot enough to melt candle wax. People didn’t just die from exhaustion or heat stroke, but from their efforts to escape the sweltering air. Some 200 people died from drowning as they dove head first into the ocean, ponds, rivers and lakes.

City authorities did what they could to handle the heat, including flushing fire hydrants to cool off streets. In Hartford, Connecticut, people rode around on free ferries and trolleys, trying to catch some kind of a breeze, while a local brewer donated water barrels to parks. Factories were closed and mail delivery was suspended as transport went haywire: boats oozed pitch and railways buckled in the heat. “The tar surface on some streets is boiling like syrup in the sun,” reported the Hartford Courant, “making things sticky for vehicles as well as pedestrians.”

A man using water from a fountain to cool his head in the intense New York City heat. (Credit: Bain News Service/The Library of Congress)

At the end of the first week, even a terrific thunderstorm did little to alleviate the discomfort. In New York, the Times reported, it was simply a few showers “accompanied by much thunder, which rumbled as early as 5:45 a.m., giving promise of big things, and then disappeared into the ocean.”

In Boston, the storm had disastrous consequences, damaging already charred property throughout the town and killing those who strayed into its path. A second thunderstorm, around the 13th, finally brought temperatures back down to manageable levels. As it did so, however, five more people died from lightning strikes. The record-breaking heat wave was over, but at still greater cost for the exhausted, grieving people of New England.

Natasha Frost

https://www.history.com/news/heat-wave-1911-weather-insane

With no air conditioning, resting under the shade of a tree, like here in Battery Park, was much more desirable than crammed indoor spaces during the 1911 heat wave. (Credit: Bain News Service/The Library of Congress)

In July 1911, along the East Coast of the United States, temperatures climbed into the 90s and stayed there for days and days, killing 211 people in New York alone. At the end of Pike Street, in Lower Manhattan, a young man leapt off a pier and into the water, after hours of trying to nap in a shady corner. As he jumped, he called: “I can’t stand this any longer.” Meanwhile, up in Harlem, an overheated laborer attempted to throw himself in front of a train, and had to be wrestled into a straitjacket by police.

In an age before air conditioning or widespread use of electric fans, many struggled to cope with this multi-day deadly heat. June had been easy enough, but a sweep of hot, dry air from the southern plains suppressed any relief from the ocean breeze. In Providence, Rhode Island, temperatures rose 11 degrees in a single half hour. New York City and Philadelphia became sweltering centers of chaos, while all across New England, railway tracks buckled, mail service was suspended and people perished beneath the sun. Total death tolls are estimated to have topped 2000 in just a few weeks.

Though temperatures never quite broke 100 degrees in the first two weeks of July in New York, the city was poorly equipped to handle the heat, and the humidity that went with it. Poor ventilation and cramped living spaces exacerbated the problem, ultimately leading to the deaths of old and young alike, with children as small as two weeks old becoming overcome by the heat.

A man resting under the shade of a tree in Battery Park, 1911. (Credit: Bain News Service/The Library of Congress)

In the peaks of the wave, people abandoned their apartments for the cool grass of New York’s public spaces, napping beneath trees in Central Park or seeking shade in Battery Park. In Boston, 5,000 people chose to spend the night on Boston Common rather than risk suffocation in their own homes. Babies wailed through the night—or failed to wake up at all.

The streets were anarchic: People reportedly ran mad in the heat (one drunken fool, described by the New York Tribune as “partly crazed by the heat,” attacked a policeman with a meat cleaver), while horses collapsed and were left to rot by the side of the road.

Around July 7, when temperatures returned to ordinary levels of July sweat, the humidity remained high. It was this, reported the New York Times, that was responsible for so many of the casualties, “catching its victims in an exhausted state and killing all of them within the hours between 7 and 10 a.m.” The New York Tribune phrased it still more dramatically: “The monstrous devil that had pressed New York under his burning thumb for five days could not go without one last curse, and when the temperature dropped called humidity to its aid.”

Children licking blocks of ice to keep cool during the heat wave. (Credit: Bain News Service/The Library of Congress)

Outside of New York, however, temperatures had climbed higher still. In Boston, people struggled in 104 degree heat; in Bangor, Maine and Nashua, New Hampshire, it reached a record-breaking 106. In Woodbury, New York, a farmer left his field when the outside temperature hit 140 degrees—hot enough to melt candle wax. People didn’t just die from exhaustion or heat stroke, but from their efforts to escape the sweltering air. Some 200 people died from drowning as they dove head first into the ocean, ponds, rivers and lakes.

City authorities did what they could to handle the heat, including flushing fire hydrants to cool off streets. In Hartford, Connecticut, people rode around on free ferries and trolleys, trying to catch some kind of a breeze, while a local brewer donated water barrels to parks. Factories were closed and mail delivery was suspended as transport went haywire: boats oozed pitch and railways buckled in the heat. “The tar surface on some streets is boiling like syrup in the sun,” reported the Hartford Courant, “making things sticky for vehicles as well as pedestrians.”

A man using water from a fountain to cool his head in the intense New York City heat. (Credit: Bain News Service/The Library of Congress)

At the end of the first week, even a terrific thunderstorm did little to alleviate the discomfort. In New York, the Times reported, it was simply a few showers “accompanied by much thunder, which rumbled as early as 5:45 a.m., giving promise of big things, and then disappeared into the ocean.”

In Boston, the storm had disastrous consequences, damaging already charred property throughout the town and killing those who strayed into its path. A second thunderstorm, around the 13th, finally brought temperatures back down to manageable levels. As it did so, however, five more people died from lightning strikes. The record-breaking heat wave was over, but at still greater cost for the exhausted, grieving people of New England.

No comments:

Post a Comment