what amazed me is that the last of the Tall ships went to the breakers just sfter WWII. They were a living memory for my parents and the whole WWII generation.

the last of the whalers were plundering hte Bering Sea as late as the 1890s as well.

At least that is mostly over as it should. we have so forgotten that before 1960, the majority of men in particular expected to live a life of physical toil with mostly a bare education. That is not so long ago.

In fact our whole working culture transitioned to power assitance. Having experienced both, I certainly am grateful. now we are transitioning to AI assisted tech working beside us to eliminate outright drudgery.

Seriously, spend just four hours picking strawberries or raspberries.

What Should We Do With an Old Sea Shant

Grappling with the complicated legacy of an unexpectedly

popular musical genre.

BY KATY KELLEHER

November 20, 2023

https://nautil.us/what-should-we-do-with-an-old-sea-shanty-447172/?

4

In an old church in Essex, Connecticut, a man with a curled gray beard that spills halfway down his red-and-white shirt takes a moment to adjust his suspenders before opening his mouth into a perfect O-shape and issuing a note so deep that the pews seem to shudder. He sings not of God or heaven or worship, but of tragedy on the water. No one joins in this ballad, though I know many of our odd congregation have the lyrics memorized. The summer air is still and warm. Tears gather in the eyes of my friends and I watch their faces surreptitiously. I’ve seen these men cry before, but not often, and never quite like this.

We went as a group to the Maritime Music Festival last June, an excursion that I suggested after spending long pandemic years in my home, listening to live recordings of folk music. Starved for physical intimacy, I found the inherent roughness of the genre comforting. I suspected my friends, most of whom I’ve known since childhood, would feel similarly. And, I should explain, I’m a romantic. Not in matters of the heart, but in matters of labor. Like so many people, I look backward with sepia-tinted binoculars. Nostalgic for lives I never (didn’t, couldn’t, wouldn’t have anyway) lived.

I forget sometimes that America was born of the water.

The age of the sail has ended, the age of the work song has largely passed, but certain genres of music persist, thanks in part to the work of activists and archivists. In early 2021, sea shanties became a viral trend, a coronavirus-infected meme that hopped platforms. Headlines followed, explainers were published, historians consulted, museum curators given a chance to speak. What was a sea shanty? Where did they come from? Why do they still matter?

In case you didn’t sing along at the time, here’s a brief primer on shanties. The word likely comes from the French chanter, meaning to sing. “Sea shanties” is redundant—all shanties are of the sea, that’s part of the definition—and within that maritime category, shanties specifically refer to work songs.

As might be gleaned from the name, work songs exist to help groups of people engage in coordinated physical labor: hauling up sails, rowing to shore, building a railroad. They function in the same way that military marching songs do and they can sound just as belligerent, though many are more lovely and haunting than the typical stomping left-left-left-right-left. Generally speaking, most of the surviving English-language shanties were formed via the process of “creolization,” taking influence from African slave songs, traditional English, Scottish, and Irish genres, popular European parlor music, and various other sources.

According to historian Stuart Frank, shanties emerged in the 1820s and 1830s and matured during the Industrial Revolution. Frank categorizes shanties into three distinct types distinguished by function. There are hauling songs (“used for pulling”) and then heaving songs (“used for pushing”) and finally ceremonial shanties, “employed for a few special purposes not necessarily related to the working ship.” Thematically, these songs vary widely. Some are about hot women in equally hot ports, some are about missing a homeland, some are about the hazards of life at sea, and some are about spotting, battling, and slaughtering whales. Some sound like strings of nonsense syllables to English-only ears but that’s because many shanties borrow heavily from other languages, and sometimes they sacrifice clear meaning for the sake of better rhythm.

To me, the most interesting work songs tend to be those that focus on the labor being performed. Singing them makes the past feel legible and alive, for although the nature of work has changed vastly, the fact of it has not. It’s still necessary for most of us to earn wages; and while we sometimes romanticize the workers of the past, we can also relate to them. Their concerns are not so dissimilar to ours. We’re all frustrated by our bosses, tired by the workday’s end, aching for home. But there’s one contemporary concern that I can’t help but insert into my understanding of shanties: I wonder about the whales.

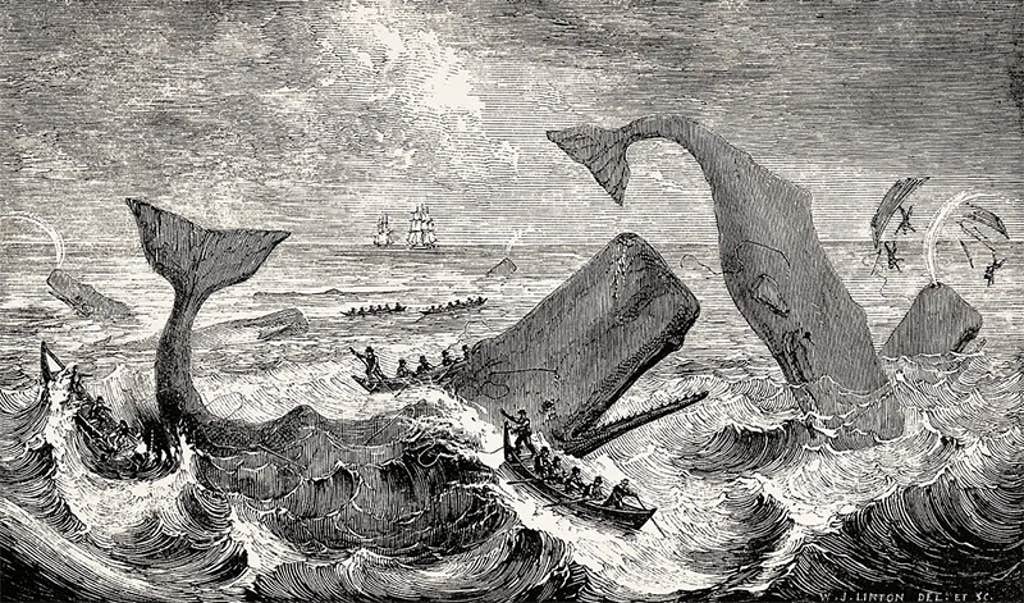

THE SLAUGHTER: In the early 18th century, as many as 2 million sperm whales swam Earth’s ocean. Today their population numbers about 800,000, up slightly from their lowest point in the latter half of the 20th century.

Illustration by Thomas Beale / rawpixel.

My friends and I expected to have a raucous, silly, good time together at the Maritime Music Festival, drinking rum, eating fried cod, and shout-singing about drunken sailors. These goals were all achieved, but we also spent more time in reverent silence than I had anticipated. During these quiet times, I found myself imagining the lives of the men who once sailed from New England into the cold Atlantic—not to mention the women and children they left behind. I forget sometimes that America was born of the water.

Historians sometimes call the period between 1450 and 1800 “The Atlantic World.” The trade routes that flowed from the east coast of North America to Europe, Africa, and South America served, per the National Museum of American History’s account of the era, to “connect the peoples and nations that rimmed the Atlantic in a web of trade, conquest, settlement, and slavery.” Maritime commerce was at the core of this world; driving up and down the east coast, you can still see the aftereffects.

The “Northeast megalopolis” that dominates the land from Portland, Maine, to Washington, D.C., is an expansion of the early coastal ports that served as anchors for the watery web. Though we don’t often associate New England with slavery, the money that came from the trade of people was crucial to building every early American state. Off the spoils of capitalism, genocide, and slavery, our northern communities grew fat like ticks. Cities bloomed and prospered; centers of industry blazed bright, lit by oil. Not petroleum, not the dark dank syrup of the Paleozoic period, but a substance even more

There’s little reason to continue to kill whales—yet we do so anyway.

It wasn’t the only option—people continued to use both candles and coal. But from the 1700s to the mid-1800s, whale oil was the preferred energy source in the United States. In 1846, American ships accounted for 735 out of the 900 whalers that sailed the globe.1 It was the fifth-largest industry in the country, one that only began to fail after the discovery of Pennsylvania’s petroleum fields in 1859.2

The legacy of this period remains with us in more ways than one might expect. New England visual style and culinary history have both been deeply shaped by sailors, whalers, and the transatlantic trade. The evidence is in our architecture, our museums, our restaurants, and even on our tables. It’s also shaped our aural culture. Although whaling songs are just one type of maritime music, they have lasted while others withered up and floated away.

The clip that kicked off ShantyTok—the favored term for this subgenre of social media video shared primarily on TikTok—featured Scottish singer Nathan Evans performing “Wellerman,” a song first recorded in the 1970s.3 Like many nautical ballads, “Wellerman” tells the story of a ship, the Billy O’Tea, and its doomed crew. It is sung from the perspective of another group of whalers awaiting the arrival of provisions, “sugar and tea and rum,” which they would receive in lieu of wages and were brought by a figure called the Wellerman.

This wasn’t an unusual setup. Exploitation was rife in whaling, which you can hear if you listen closely to the old songs. Many sailors started their outward journey in debt, and some finished it in debt, too. Frustration with working conditions was a common theme; every variation of “Across the Western Ocean,” an off-riffed shanty from the North Atlantic, contains similar complaints about “hard times,” “low grub,” and “foul winds.” Many versions of the tune also describe failing health and poor wages; quite a few even boldly lay the blame for the sailors’ suffering directly at the feet of their captain or his first mate.4

This is not the case in “Wellerman.” Here, the crew’s dissatisfaction is more obliquely expressed. Nestled within the song of waiting is a narrative of action. The lyrics are heavy with tension: not just the narrative type that comes from switching perspectives, but also the tension that arises when glorious lines fail to rise higher than brutal reality.

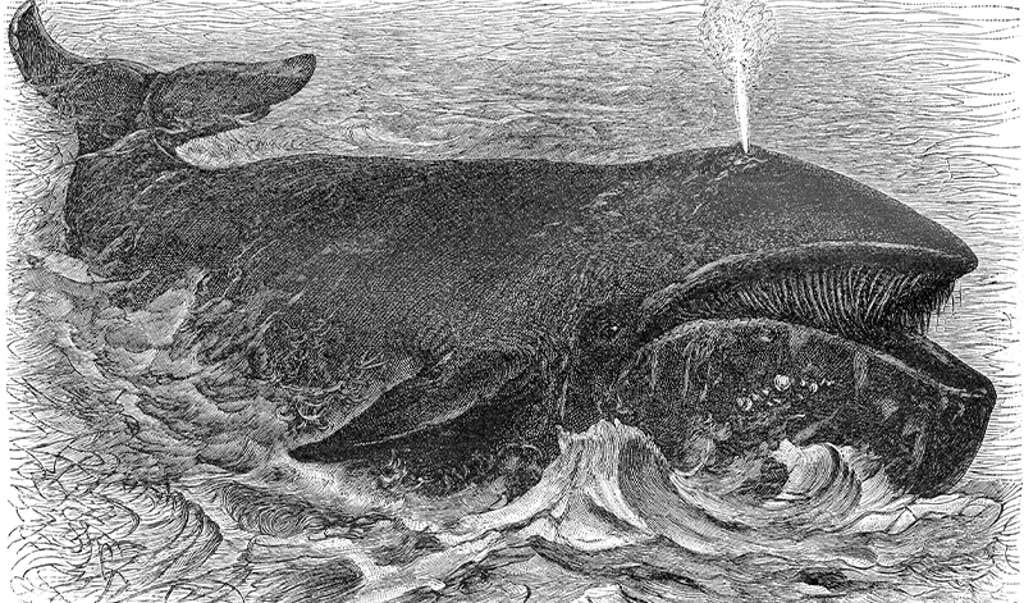

Nautilus Members enjoy an ad-free experience. Log in or Join now .UNFORTUNATE QUALITIES: Bowhead whales swim slowly and float when they die—traits that made them a favorite target of whalers. By the 1920s fewer than 3,000 bowheads survived. Illustration by Hein Nouwens / Shutterstock.

According to the legend, there was once a group of hardworking men, led by a noble captain—whose mind, we’re told, “was not of greed”—who became entangled in an epic battle with a beastly right whale. “She’d not been two weeks from shore / When down on her a right whale bore,” go the lyrics, shifting responsibility from the men to the whale, who tows the ship for “forty days or even more” as they wait for the animal to die.

It’s a simple enough story, one that starts out true to life and ends with the tall tale of an infinitely energetic whale, capable of surviving the most incredible odds. In order to get to the point where the whale is towing the ship, the men of the Billy O’Tea would have been lowered into rowboats from which they launched barbed harpoons into the whale’s side. Their ultimate goal was to pierce the lungs or heart, but first whalers focused on getting a harpoon lodged behind a flipper so they could tow the body behind their ship.

What happened to the Billy O’Tea’s crew, though, is a role reversal. Instead of dragging and dismantling the whale’s body, the whale tips over their rowboats and pulls them off course. We’re to assume that many lives were lost in addition to property: “All boats were lost, there were only four / But still that whale did go.” As far as the singers know, “the fight’s still on,” implying that maybe no one survived, maybe none of this ever happened, maybe the monstrous cetacean was as much a fable as Melville’s white devil.

Though “Wellerman” describes whalers from New Zealand, it could also have been sung of whalers in the Atlantic and the Arctic. Here, too, whales were stabbed, stabbed again, dragged, dismembered. Here, too, men sang of their conquests. Dated to the 1850s, “Wild and Ugly” described a sailor’s frustration with his captain for making them hunt dangerous sperm whales rather than the smaller, weaker bowhead whales. “All these whales are wild and ugly,” he sings, “everywhere we stray.”

“The Weary Whaling Grounds” contains a particularly arresting image of carnage: “the blood in a purple flood / from the spout-hole comes a-flying.” Hearing these lines sung feels cathartic, much in the same way that watching a Quentin Tarantino film can evoke a sense of secondhand liberation, but it’s also frightening. How easily we can slip from one register to another, how quickly bodies can become objects, lifeblood transmuted into pure, glorious color.

Our surviving nautical songs tell us surprisingly little about the oceanic world. These are deck tunes; they infrequently go underwater and for the most part are human-focused, dealing with our vices and virtues and predicaments. When whales are mentioned, the relationship between man and animal is simple. The creatures are either improbable monsters or products. When living, breathing cetaceans do appear, they are shadowy figures: not individuals with lives of their own—there are no Moby Dicks here—but rather the whale, a thing to be hunted and conquered. The anonymous, unknowable leviathan.

“The concept of ‘the whale’ is something that really grates for me,” says Philippa Brakes, a New Zealand-based behavioral ecologist and research fellow with Whale and Dolphin Conservation. “It makes as much sense as calling the great apes, including us, ‘the ape.’ ” She argues that reducing an entire order to a single word allows us to create an “artificial separation” between humanity and nature. It flattens out our many complex relationships with creatures into one single drama. In reality, Brakes says, our relationships to cetaceans have always been complex and multilayered. Sometimes they’re commodities, sometimes they’re deities, sometimes they’re both or neither.

Do whales feel transcendence when they sing, as we sometimes do?

In the contemporary world there’s little reason to continue to kill whales—yet we do so anyway, with exploding harpoons, drive hunts, and ship strikes, despite our increasing fascination with their otherworldly existence. Brakes suggests that our strong emotions about these creatures comes from our noticeable similarities. Humans and whales are both warm-blooded, have long lives, and transmit information throughout our communities. Many species of whales coordinate and cooperate. They sing.

Do whales feel transcendence when they sing, as we sometimes do? I like to imagine this possibility. Maybe their songs can be, like ours, tools for achieving their goals. The important fact is that they do have culture. We are not separate from them; we exist in the same entangled web. Much of Brakes’ work tries to illuminate the strands that bind us to aquatic creatures. “It’s about bridging the gap between human exceptionalism and the rest of the world,” she explains. “Although we’ve held a dominant position for such a long time, we’re still part of a larger biological system, whether we like it or not.” Krista Tippett, host of the On Being podcast, uses the phrase “revelations of entanglement.” The world is full of communication, information exchange, and song. We’ve been able to hear it, but we’ve ignored it for far too long.

The shanty is a relic of a different era, one that gets romanticized and sugar coated. But it’s also a reminder of what song can do. It can bridge gaps, transmit information, and even unlock a sense of deeper connection. As we finish our conversation, I suggest to Brakes that perhaps what we need is a tune for the 21st century, one that will help us direct our desires and coordinate our efforts. “We live in this particular time when anything can go viral in an instant. That could be such a tool for change,” she agrees. “Maybe that’s what we need: the perfect work song. One that can stimulate us all to take the right individual action to reduce the temperature rising above 2 degrees.”

It strikes me as deeply ironic that ShantyTok took off during a time of social upheaval and massive protests. The summer of 2020 was a moment when change felt possible, when forward momentum felt like it might carry us somewhere new. But it’s been several years, and little has changed. Money continues to matter more than life, the globe is still warming steadily, and blood continues to flow, purple and red, into the water and onto the pavement.