A life thrown away.. Yet the young are drawn in like flies to these populist drama.

The succeeding economic losses are actually massive over the missing persons potential life.

That loss is never truly recoverable as well .

My Sister Was Disappeared 43 Years Ago

A casualty of Argentina’s so-called Dirty War, Isabel haunted my childhood like a ghost. Then I started searching for her.

Courtesy of Daniel Loedel / The Atlantic

Story by Daniel Loedel

JANUARY 17, 2021

The report from the Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team included 20 photos of my half sister’s bones—nearly as many photos as I had ever seen of Isabel herself.

The ones of the bones punctured by bullets—her rib, her pelvis, her humerus—did not move me as much as those of her skull. It was so old-looking, like one of those prehistoric craniums of Homo sapiens, the nose bashed in, some of the teeth missing, that earthen coloring. The skull had lain in a common grave, untouched for more than 30 years, before being taken to a lab, where it remained officially unidentified for about another 10. The sight of it destroyed me. In all the photos I had seen, Isabel looked incredibly young, with a cherubic beauty—round cheeks, light hair, searching blue eyes. She had been murdered and disappeared by the military dictatorship in Argentina in January 1978, when she was just 22. Staring at those photos of her skeleton in March 2018, I was eight years older than she ever had been. Never before had I quite grasped how much time she hadn’t gotten to live, to age and grow old, until I saw her bones, and realized they had been aging without the rest of her.

One photo showed a bullet that had remained lodged in her skeleton the whole while. The sight would have been a comfort to many because, along with the bullet holes in her bones, it suggested that Isabel had been killed in a gunfight, not imprisoned and tortured, as most of the regime’s victims were.

I was the recipient of the report because, despite being born in New York 10 years after Isabel was killed, I was the legally designated recipient of her remains. The anthropology team had tried to reach my father and my half-brother, Enrique, around 2012, as part of its project of identifying the disappeared victims of Argentina’s so-called Dirty War—the period from 1976 to 1983 in which the U.S.-backed military dictatorship kidnapped and killed tens of thousands of supposed dissidents in the name of fighting off communism. But the team’s letters to my family went unanswered. There were valid explanations, including the vagaries of international mail, address changes, and so on. I had little doubt, though, about the main reason there was no response. My father, in particular, had long ago chosen to leave this part of the past buried.

Growing up, I almost never heard mention of Isabel. At most, she was a kind of ghost hovering in the background. A single black-and-white photo of her hung over my father’s bed, highly pixelated because it was a blowup of the yearbook photo he kept in his wallet after he moved to the U.S. For a long time I didn’t know who it was, but even as a child, I was aware that I shouldn’t ask.

Understanding came to me obliquely and incompletely. There was the story my father once told me about carrying Isabel as a young girl up the beach after she’d stepped on something and her foot had started gushing blood. He wept as I had never seen him weep before, and I intuited then that it might have been the last time he felt he had protected her. There was the trip to Uruguay in my teens, during which a cousin showed me a photo of Isabel with her boyfriend, smiling mischievously at the camera. My cousin told me that the boyfriend had been murdered along with her. The expression on her face—happy, secretive—told me that she had known joy as well as sorrow.

But no one told me what she was like, or who she’d been besides my sister. I gathered that she was rebellious, brave, idealistic. But the only attribute I comprehended with any sort of reality was: disappeared. My sister’s gone-ness, the silence around her, was so absolute that I barely dared to peek any further behind that curtain than my father did.![]() The author’s half sister Isabel (Courtesy of Daniel Loedel)

The author’s half sister Isabel (Courtesy of Daniel Loedel)

When he and I finally had an extended conversation about Isabel—whom I’d chosen somewhat flippantly as the subject for my college-application essay, as a way of conveying my own desire to do good in the world—I got the impression that she’d been killed for doing things like tagging walls and distributing political pamphlets. But Enrique later told me she was in fact one of the Dirty War’s rarer victims: She’d been in the armed resistance, living in hiding, with weapons in her home.

Even after I’d graduated from college and gone to live in Buenos Aires for a year, I did not take an interest in Isabel’s life or the circumstances of her death. Chasing after girls and partying until sunrise, I was the same age at which she’d died, with a gun presumably in her hand. When a friend, a fellow expat, suggested visiting the ESMA, a former naval academy that had served as a torture center and had recently been converted into a museum and memorial, our Argentine friend declined, saying with a shudder that it gave her the creeps: “Me da cosa”—an idiom that literally translates to, “It gives me thing.” I declined as well, without giving a reason, but thinking, It gives me nothing. Neither of them knew I had a half sister who was among the disappeared.

In March 2017, at the age of 85, my father underwent surgery for colon cancer. I believed he was going to die.

My father was a nihilist. Death was as meaningless as life, he’d always insisted, almost evangelically, and he was not afraid of it. When I was 8, he recited Macbeth’s “Out, out, brief candle!” soliloquy to me, uttering the last two words with an exuberant flourish—“Signifying nothing”—and most of the time his philosophy retained that over-the-top relish. But before his operation, we got into a heated fight over this stance, with raised voices and fists slammed into tables. It culminated when he told me more or less to shut up about life having any meaning unless I’d had a daughter whose life was cut short.

I decided, waiting in the hospital corridor, to finally look into that life. Whether it was because my father’s seemed to be ending or because, if it didn’t, I wanted to give him some degree of peace, I don’t know.

I planned a trip to Argentina and reached out to Isabel’s boyfriend’s family. I had learned that they’d set up a Facebook page honoring his memory, and when I looked at it, I saw videos of the interment ceremony they’d held for him in 2015, after the forensic anthropologists had identified his remains in 2013.

I informed my father and my brother about the possibility of doing the same, saying I could get the necessary blood test when I was there. They were uninterested. Those were just bones, not Isabel. What did it matter where they were? Isabel would have preferred to remain in a common grave with her peers, in any case. (That she was in a forensics lab at this point did not seem to make much difference.) Besides, unlike other families, they had closure about what had happened—they had always known how Isabel had died. The story, which by then I’d heard, was that Isabel’s mother, having figured out where Isabel had been in hiding, had gone to the house and seen bullet holes in the exterior; the landlady answered the door wearing a dress of Isabel’s and told her about the “terrorists” who’d been caught there some weeks earlier.

My other half sister, Bonnie, was the one who persuaded me to take the test. She didn’t like the idea of Isabel sitting on some lab shelf, she said. Bonnie, like me, was American-born and a half sibling to Isabel. But she had been 12 when Isabel was killed; she remembered her well. She remembered Isabel carrying her on her shoulders.![]() Isabel and Bonnie Loedel (Courtesy of Daniel Loedel)

Isabel and Bonnie Loedel (Courtesy of Daniel Loedel)

Still, I felt like a fraud as I pursued this pseudo-quest, and the feeling did not go away. Not as I made the appointment with the forensic anthropologists, who made their pitch for how identifying victims helped families and society alike. Not as I returned to Argentina and met Isabel’s boyfriend’s brother, and some cousins who were eager to speak openly of her after all these years. Not as I visited some of those torture centers turned memorials and, in one of them, the Ex-Olimpo, flipped through the booklets that family members had made to commemorate the victims, sweet, makeshift albums of photos and letters and expressions of gratitude. Not as I went to see the dinky house in a shady neighborhood in which Isabel had died. A scraggly watchdog was there, and it barked at me until I scurried off in fear.

The feeling of fraudulence was worsened by the fact that I’d decided that spring to write a novel inspired by Isabel, with a character based so directly on her that she shared her name. I’d attempted versions of this before: innumerable short stories fueled by the motif of “disappearance”; a floundering essay titled “Defined by Absence,” in which I tried to understand her influence on me and wound up with a largely blank page; my college-application essay, in which I discussed her fight for change and the desire it fostered in me “to have an impact”—an irony, because my father always contended that Isabel’s particular fight was foolhardy and in fact had no impact at all.

But this time the undertaking was bigger. I was re-creating my own version of Isabel, trying, in essence, to resurrect her. The plot reflected that: What began as a realistic depiction of her story evolved into the tale of a man literally searching for her ghost. A friend and former lover of hers plagued by guilt for his role in her fate descends into the warped underworld of memory and the 1970s Argentina he’d managed to escape, and there tries to bring her back to life and grant himself redemption.

Still, I wondered: Was this just some petty artistic theft in which I was engaging, plundering another person’s tragedy—another country’s—in typical American fashion? What right did I have to claim the role of Isabel’s redeemer when those closest to her wanted to leave her in the ground? And how dare I reignite this pain of theirs that I had never felt, that for me had been merely a shadow several decades removed?

My appointment with the forensic anthropologists was near the end of my trip—I’d wanted to put it off. It turned out that my blood sample, as a half sibling, would not be enough for confirmation. They would need my father’s, too. They sent me home with an ordinary-looking piece of paper with two squares, onto which he was supposed to squeeze some drops of blood.

On my return, I went over to my father’s for dinner one night. He squirmed when I pricked his finger, complaining that I would take every ounce of hemoglobin in him, but he did not object even once to taking the test.

About two months later, I got the report.

How strange it was to see the actual skeleton of the person I’d been trying to reimagine in fiction. I’d been putting all this flesh and skin on my rendition of Isabel, sewing together my own Frankensteined incarnation of her from scraps of knowledge as various as her love of roller coasters and dulce de leche and her fiery resolve for the cause, which could sometimes border on selfishness—and here she was stripped of every detail, literally down to the bone.

When I was done staring at Isabel’s skull and crying about her—for the first time—I emailed my father. Not the whole thing, of course; I couldn’t let him see those pictures. Just the news of the match and the coroner’s conclusion about the cause of death, which we already knew.

My father didn’t reply, and eventually I called him. He sounded sad, but all he said was that the report’s bureaucratic language had been difficult to understand.

There was much more bureaucratic language to deal with before we could set up the interment ceremony. The report had to be validated by judges, I had to sign things that I didn’t fully grasp, the cemetery in La Plata where Isabel’s boyfriend was interred had to make room for her in the mausoleum. Everything dragged on.

Finally, though, we settled on a date: March 28, 2019. I alerted everyone in the family. Bonnie would come, of course, she said. But Enrique wouldn’t; he had familial obligations and said he’d made his peace with it already. My father wouldn’t, either; he gave no excuse, just stated immovably that he would not go.

I shouldn’t have been, but I was surprised. Not long before, I’d caught him on Google Street View, staring at the house in which Isabel had been murdered. I’d given him the address. I should have seen it when she was living there, he’d told me, his eyes teary.

Here we must pull back the curtain, listen to what’s behind the silence. First, the cultural reasons: Although Argentina’s military dictatorship technically lasted only seven years, from 1976 to 1983, they were the bloodiest in the nation’s history, and few except the junta leaders themselves were put in prison. For years, people continued to encounter their former torturers at bus stations, their rapists in cafés. For years, the armed forces maintained power at a distance, with complete immunity. For years, there were no formal funerals for the disappeared. And for years, those who had resisted, almost all of whom were eradicated, were viewed with suspicion and blame, and those who had kept quiet, passively acceding to the junta, continued to keep quiet. There is a reason my Argentine friend was squeamish at the thought of what happened in the ESMA and didn’t want to see it.

My family’s reasons for silence overlap with their country’s, of course. They felt shame about Isabel taking up arms against the regime—many said they wished she had used peaceful methods instead, as if that would have saved her from getting killed. Most of them had abandoned their roots and the settings of their memories, and those who hadn’t still carried their own entangled traumas that they did not wish to relive, another lost relative or their own experience in a torture center or recollection of waking up in the middle of the night as a kid with a machine gun pointed in their face.![]() A woman tries to prevent detention of a young man by police during an anti-government rally in Buenos Aires during the last days of Argentina's Dirty War. A 1976 coup resulted in a seven-year military dictatorship in which tens of thousands of people were killed or "disappeared" at the hands of the military. (Horacio Villalobos / Corbis / Getty)

A woman tries to prevent detention of a young man by police during an anti-government rally in Buenos Aires during the last days of Argentina's Dirty War. A 1976 coup resulted in a seven-year military dictatorship in which tens of thousands of people were killed or "disappeared" at the hands of the military. (Horacio Villalobos / Corbis / Getty)

They felt guilt, too. The guilt of complicity, yes—many of us now lived in the country that had enabled the regime’s practices, as part of its touted war against communism—but more important, the guilt of survival. For Enrique, who escaped to the U.S. to live with my father a year before Isabel was murdered, and who spent much of the year afterward wandering the unfamiliar streets of Queens alone until dawn, I have to believe that is the core of it.

My father’s guilt is harder to pin down. There is the basic guilt of a parent unable to save his child, the child he once carried bleeding up the beach. There was his own leftism, the fondness he expressed for Che Guevara types when Isabel was at an impressionable age. Or had it been his poor relationship with Isabel—he’d left their home and divorced her mother in the ’60s—that led her to resist authority with such vehemence? Or was it, as with Enrique, simply that he’d failed to get her to the U.S., failed to die before her, succeeded in living more than 60 years longer than her?

In all of the fights we had leading up to the interment ceremony, my father never gave me a real explanation for his refusal to attend. You just can’t understand, he’d say. There is no peace to this, he’d say. No redemption. No meaning. His chance—he never expressly said at what—was long over.

I had my own guilt about Isabel, too. Not only for being her after-the-fact champion, a fraud. But for being alive myself, and for having had such a wonderful, loving father, one who, to my mother’s occasional annoyance, refused to leave me alone as a child when I cried. Someone once commented that my father was a much better parent to me than to any of his other children. The reason is obvious: I was the only one born after Isabel died.

There was also this, going back to my college essay: I did truly want to have an impact now; more than anything, I was afraid to “disappear.”

In the end, neither my father nor Enrique came to the ceremony. I had several nightmares leading up to it in which no one else showed, either, and I was alone with her bones, placing them wordlessly in a big common grave just like the one she’d been dug up from. I knew that a couple of relatives on her mother’s side in La Plata would attend, and three cousins on our side, two of whom were coming from Uruguay. Her boyfriend’s brother, the kind woman from the forensic-anthropologists team who had made all the arrangements, and me and Bonnie. It would be enough, I told myself repeatedly, feeling panicky and ashamed.

The ESMA, the former torture center, was where the forensic anthropologists now worked, and it was there that Isabel’s bones were handed over to me, in a box. Bonnie and I put the photo of her and her boyfriend on it along with a plaque bearing her name, and drove to the cemetery in La Plata. I held on to the box in the car, hugging it with weird affection in my lap; it was the closest I had ever physically been to Isabel.

Walking to the mausoleum with the box in my arms and Bonnie behind me, I realized the crowd that had gathered was much bigger than I’d anticipated. So many strangers were there—strangers to me, not to Isabel. Her boyfriend’s brother had gotten an announcement to run locally, and as a result her high-school and college friends were there, even her childhood nanny—a wizened old woman who wept with such love and gratitude that I nearly wept, too.

We gave speeches honoring Isabel, and then I took the box with her bones and placed it on the mausoleum shelf, next to her boyfriend’s box, and many others. The crypt was a memorial for victims of the regime; she would lie with her peers, after all.

I called my father after the ceremony and told him everything about it, like an excited schoolboy. He did not say he regretted missing it. But he did thank me for organizing it. He said I had given closure to the other attendees, peace, redemption, healing—all the things he did not believe he could have himself. And I knew he was saying it did not matter that he would never have those things.

Do you feel good? he asked me during that phone call, trying to partake in my excitement. Do you feel proud? Do you feel close to your sister? I told him yes, no, I don’t know. That it didn’t matter how I felt.

We were silent a minute. But it was a much richer silence than any we’d had before.

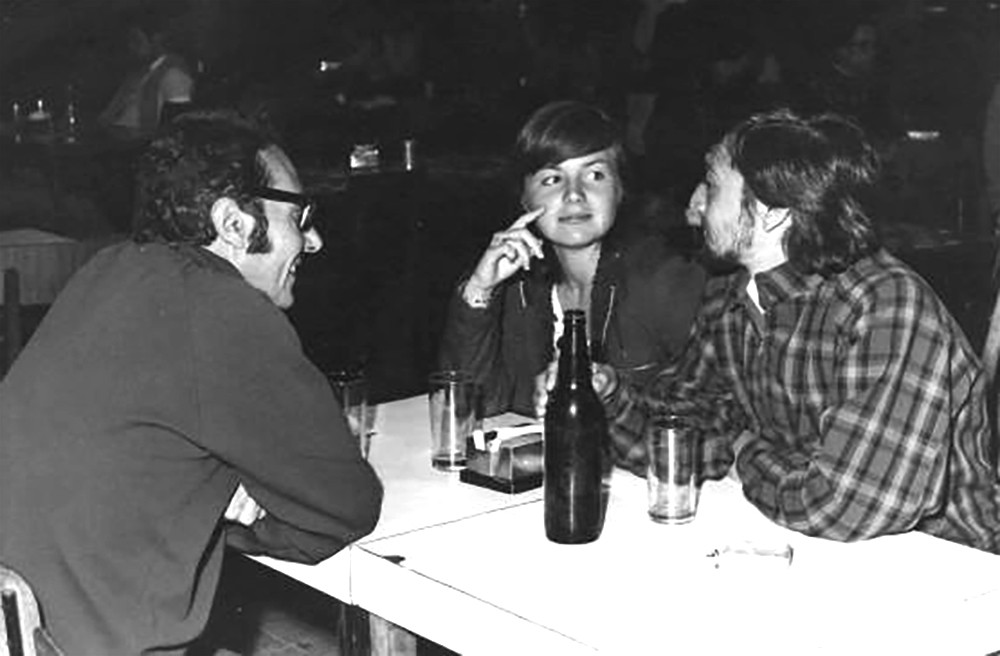

The author's father, Eduardo Loedel; Isabel Loedel; and her partner Julio DiGiacinti. (Courtesy of Daniel Loedel)

Later that year, I finished my novel. And the year after that, without much discussion of what it meant, my father took it upon himself to translate it into Spanish. That is, in a sense, to write the story of Isabel in his own words, to give his own voice to it, for the first time.

Of course, that story wasn’t solely hers now, any more than the translation was solely my father’s. My Isabel was more painting than photograph, shaded by my imagination as well as the innumerable recollections of others. The search for ghosts, the effort to prevent the dead from being entirely disappeared, is inevitably a communal one, a strange multi-generational game of telephone. And, as in that game, all you get and have to pass on is a whisper.