Without question, we have barely begun to properly exploit the food producing capacity of our trees. Even better we actually need those trees in order to enhance our open field agriculture in the best way possible.

Here is a good intro to what we can squeeze from what we already have.

I do observe that most leaves are generally bitter, yet this is a characteristic easily adjusted as well. Add fermentation and we have a lovely feed-stock to at least feed animals. In short, we have not barely begun to think it out.

And simply having massive forests of pine trees producing high quality nuts is eminently practical now. Choice species are available.

Edible Trees: Foraging for Food from Forests

By Jesse Vernon Trail

http://www.americanforests.org/magazine/article/edible-trees-foraging-food-forests/

Fall Sugar Maple (Acer saccharum). Credit: Http://www.forestwander.com via Wikimedia Commons.

Most of us know of, and greatly appreciate, the wild and

cultivated fruits, nuts and berries that come from trees. However, few

are aware of the edible yields (and great value) that several of our

trees have to offer. Aside from producing delicious snacks, such as

apples, cherries, walnuts and chestnuts, some trees provide other edible

parts: bark, leaves, twigs, seeds, pollen, roots, new growth, flowers

and, of course, sap used for syrup.

For example, did you know that the young leaves and even the seeds of

many of our maple trees are edible? Maple trees provide more than the

familiar delicious maple syrup! Also, did you know that the inner bark

and young twigs of many of our birch trees are edible? Birch trees can

also be tapped for a sweetish sap/syrup. Then, there are the immensely

valuable pines, with their edible inner bark, seeds and so much more.

Deciduous Trees

BEECH, FAGUS

American beech leaves (F. grandifolia). Credit: Louis-M.Landry

The American beech, F. grandifolia, is an

exceptional, magnificent and majestic shade tree that definitely

deserves to be grown more often in the landscape. A slow-growing native

of eastern North America, the tree can grow to about 100 feet

tall, often with a nearly equal spread. It has grayish bark and dark

green foliage that turns golden bronze in autumn. The small, edible nuts

are very tasty but not that well known. Young leaves can be cooked as a

green in spring. The inner bark, after drying and pulverizing, can be

made into bread flour, though this is probably best considered as a

survival food.

[ perfect for grafting larger nut bearing stems.]

[ perfect for grafting larger nut bearing stems.]

BIRCH, BETULA

The birch species are well known, especially the strikingly beautiful

white-barked varieties. The inner bark of birches is edible, making it

an important survival food. Many have kept from starving by knowing

this. Native peoples and pioneers dried and ground the inner bark into

flour for bread. You can also cut the bark into strips and boil like

noodles to add to soups and stews or simply eat it raw. In spring you

can drink the tree’s sap directly from the tree, or boil it down into

a slightly sweet syrup.

LINDEN, TILIA

The linden (or basswood) is often a well-shaped tall tree, with grey

fissured bark. The young leaves in spring are pleasant to eat raw or

lightly cooked. The flowers are often made into a soothing, tasty tea.

MAPLE, ACER

The sugar maple, A. saccharum, is a beautifully formed tree.

It provides us with some of the best and intense autumn foliage color,

ranging from brilliant orange to yellow to bright reds.

Sugar maples have distinctive, slightly notched, three-lobed leaves, whereas those of the black maple, A. nigrum, are more shallowly notched. The bark of the black maple is almost black in color. The five-lobed leaves of the silver maple, A. saccharinum, have narrow and deep indentations between the lobes. The undersides of its leaves are notably silvery-white in color.

The sugar maple is famous for the deliciously sweet syrup you can

make from its sap. But, few are aware that many other species of

the larger maple trees can also be tapped for an edible sap. Among these

include: the black maple, whose sap tastes almost identical to that of

the sugar maple; and the silver maple, also providing an equally

sweet-flavored sap. The syrup you can make from other maples varies

considerably in flavor and quality, but feel free to experiment. Native

peoples and pioneers drank the fresh sap from maples in spring, as

a refreshing drink.

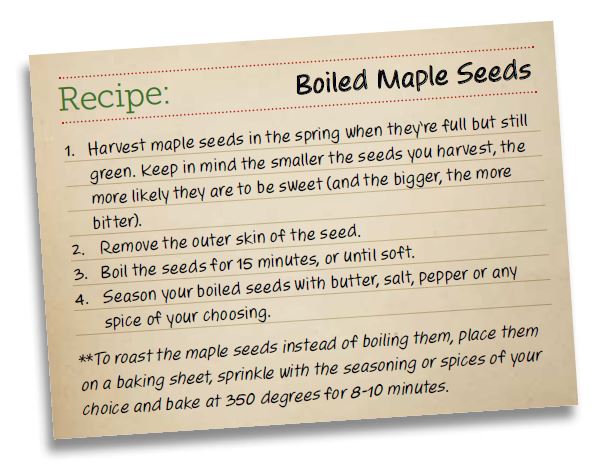

The inner bark of maples can be eaten raw or cooked — another

survival food source! Even the seeds and young leaves are edible. Native

peoples hulled the larger seeds and then boiled them.

MULBERRY, MORUS

The mulberry, M. alba and M. rubra, are

mediumsized, fruit-bearing trees, with a short trunk and a rounded

crown. The twigs, when tender in spring, are somewhat sweet, edible

either raw or boiled.

WALNUTS, JUGLANS

All Juglans species can be tapped for sweet-tasting syrup, particularly black walnut and butternut.

OAKS, QUERCUS

The oaks are mentioned here, for it is not that well known that the

acorns are edible. All acorns are good to eat, though some are less

sweet than others. Some, like red oak, Q. rubra, are bitter tasting, while others like white oak, Q. alba, sometimes have sweet nuts. The bur oak, Q. macrocarpa, often bears chestnut-like flavored acorns.

[ soaking in cold water will strip out the tannin s. Grind the acorn seeds first to do this - arclein ]

[ soaking in cold water will strip out the tannin s. Grind the acorn seeds first to do this - arclein ]

POPLAR, POPULUS

The Populus genus includes aspens and poplars. Their somewhat sweet,

starchy inner bark is edible both raw and cooked. You can also cut

this into strips and grind into flour as a carbohydrate source. Quaking

aspen, P. tremuloides, catkins can also be eaten.

[ this super common and quick growing so well worth trying. arclein ]

[ this super common and quick growing so well worth trying. arclein ]

SASSAFRAS, SASSAFRAS

The green buds and leaves of a sassafras (Sassafras albidum). Credit: Matt Jones via Flickr.

Sassafras tea (mainly from the young roots) is well known, and its

pleasantly fragrant aroma is unmistakeable. The young,

green-barked, mucilaginous twigs of this small- to medium-sized tree,

when chewed, are delicious to many. The green buds and young leaves are

also delicious. Try them in salads! Soups and stews can be thickened and

flavored with the dried leaves (but, remove the veins and hard portions

first).

SLIPPERY ELM, ULMUS RUBRA

This medium-sized tree is well known for its many herbal medicine

uses. The thick and fragrant inner bark is extremely sticky, but

provides nourishment, either raw or boiled.

WILLOW, SALIX

The inner bark of the willows can be scraped off and eaten raw,

cooked in strips like spaghetti or dried and ground into flour. Young

willow leaves are often too bitter, but can be eaten in an emergency —

it is a survival food!

Conifers (in particular, The Pine Family, Pinaceae)

The entire pine family comprises one of the most vitally important

groups of wild edibles in the world, particularly for wildlife. The

inner bark and sap is very high in vitamins C and A, plus many

other nutrients. And, when eaten raw or cooked, its bark has saved many

from starvation and scurvy. You can cut the inner bark into strips and

cook like spaghetti, or dry and ground into flour for bread and

thickening soups and stews. The sap in spring can be tapped and drunk as

a tea.

Even pine needles, when young and starchy, are rich in nutrients,

like vitamin C, and are reasonably tasty. These are not usually eaten,

but rather chewed upon for about five minutes, swallowing only the

juices. Perhaps a better alternative is to make a tea with the needles.

Pine or fir needles make a fine tea in winter.

The cones of a Korean pine (P. koraiensis). Credit: Peter GW Jones via Flickr.

Then, there are the edible cones, seeds and pollen of the Pinus

genus. The woody cones that produce seeds within their framework are

female. These are delicious when shelled and roasted. Nutritious pine

nuts are often not considered for food because they are too tiny

and hard to get at (a hammer or rock will be needed). However, there are

a few pine species that provide delectable pine nuts (seeds) that can

be as large as sunflower seeds or larger. Here is a small selection of

these: the Korean Pine, P. koraiensis; Italian Stone Pine, P. pinea; and Pinyon Pine, P. edulis.

The soft male cones and pollen are also edible, but the taste is very

strong, so is better if used in cooking. In spring many of these male

cones produce copious quantities of pollen, so much so, that you can

practically scoop it up from the golden carpet it makes on the ground.

The pine family includes genera such as: the pines, Pinus; spruces, Picea; larches, Larix; firs, Abies; and the hemlocks, Tsuga (not to be confused with the totally unrelated poison hemlock).

Certain genera of another plant family, Cupressaceae, specifically two species of arborvitaes, Thuja, cedars, also have an edible and nutritious inner bark. These are: western red cedar, T. plicata (in particular); and eastern white cedar, T. occidentalis. Native

peoples would harvest and dry it, then grind it into a powder for use

when travelling or as an emergency. On the advice of native

peoples, Jacques Cartier, a French explorer, used the eastern white

cedar to treat scurvy among his crew.

Sap, Syrups and Tapping

Properly selecting and tapping trees for syrup can be a detailed process. Credit: Alan Sheffield via Flickr.

There are a relatively surprising number of trees that can be tapped

for their sap and syrup. However, be forewarned; many of these offer a

bland, bitter or almost tasteless flavor and quality. For example, you

will find that tapping a hickory tree will result in unsatisfactory

tasting syrup. Whereas, tapping certain other nut trees, like butternut

and black walnut, will provide you with quite a fine-tasting

syrup. Also, the native peoples tapped the sycamore tree, Platanus acerifolia,

but this syrup is considered much too dark and strong flavored by most

people. The maple by far yields syrups of the best quality and taste,

and the best of these is from the sugar maple, or black maple, and

followed closely by the silver maple.

Properly selecting and tapping trees for sap can be a detailed

process, so here we will address just the basics. You can purchase the

necessary spiles and pails for sap gathering, or for better enjoyment do

it on your own.

First, in most instances, you will want to select trees that are at

least 18 inches in diameter. A rough estimate of how much finished syrup

you will get per tap is about one to two quarts, or about one gallon

of syrup per year, per tree.

Cut a V-shaped gash into the tree (an age-old method of our native

peoples), at the base of which you can drill a hole about 2 inches deep

and close with a peg. Then, when you are ready, remove the peg and

insert your spile. A spile is the means to convey the sap from the tree

trunk to your bucket or pail. This is essentially a hollow tube with a

spout end. It can be made from a wide range of materials from metal to

bamboo. One of the best is made from a sturdy, hollowed out twig or

branch of a staghorn sumac, Rhus typhina. Or, you can use the

lid from a tin can for a sort of spile. Just smooth the rough edges

first. Make a single bend in the lid and insert it into your tree tap

hole. Drive a small nail into the tree to suspend your bucket or pail

from.

Then, it’s just a matter of boiling the sap with water, and spooning

off the characteristic scum as it rises. The best ratio is around 35

parts of water to one part sap. The water evaporates over time,

leaving a clear amber syrup. Strain carefully.

For sugar, continue boiling until a test portion of the syrup forms a

very soft ball in cold water. Remove from the heat, agitate with an egg

beater and pour into dry molds. Delectable!

Jesse is an author and instructor in environment, ecology,

sustainability, horticulture and natural history. Check out his first

book, “Quiver Trees, Phantom Orchids and Rock Splitters: Remarkable

Survival Strategies of Plants”

at www.ecwpress.com/products/quiver-trees.

No comments:

Post a Comment