It is a natural conjecture, but Ireland was an anchor point for the Atlantean Global sea trade that reached everywhere and inspired mining and pyramids. All available evidence suggests a veneration of the sun in all their known culture locations. This includes the Americas in paricular.

Ireland was also culturally isolated until the advent of Christianity. It could preserve their system until Christianity arrived. Thus it provides as good a snapshot as possible along with the Inca and the Aztec. Recall also that the earliest reports out of Anatolia tell us the same story.

The overlay of later doctrines has hidden all this, but the Atlantean world dominated through at least a thousand years everywhere during a time in which the non civilized lacked real mobility and posed little threat.

Baal worship is solar and is likely central to the Atlanteans. There has also been an overlay of slander folded into what we know so much can not be trusted there. Nothing so universal could actually sustain aberrations for long..

Was Prayer to the Ancient Solar Gods enough to Change the Renowned Irish Weather?

20 April, 2018 - 19:02

lizleafloor

https://www.ancient-origins.net/human-origins-religions/prayer-ancient-solar-gods-enough-change-renowned-irish-weather-009928

Ireland’s

history is rich in dramatic myth and mysterious legends. The

significance of the natural world, and most importantly the sun, was

obvious in the daily lives of the pre-Christian Irish.

Solar gods are found around the world, but, was the solar symbolism

strong in the damper, colder climates because it was (and remains) so

physically welcoming? Did the ancients of Ireland worship the sun gods

to try and improve the well-known foggy Irish weather in the hope for

more time in the blessed sun?

As Above, So Below

The brilliance and warmth of the sun was replicated on earth with

fires – sometimes loud, roaring fires that could be seen from afar.

These bonfires were likely not just a way to keep warm or illuminate the

night sky, but also served as a conduit between those on the ground and

the gods of the sun – and weather – in the sky, who, by their physical

manifestations on earth such as thunder, lightning, fog, rain, now,

clouds, and even eclipses, seemed very much in charge!

Irish sun gods, as in other mythologies, are usually portrayed as

strong and successful during the summer but will lose out to forces of

winter when their radiance and power is on the downswing. They are often

depicted with shining, golden hair, and fly across the sky in

horse-drawn chariots, shooting arrows of light at their quarry. They are

friends or helpers to mankind, and champions against darkness and

demons of the night.

The Mysterious Origins and the Birth of Celtic Solar Gods

Modern archaeologists and historians continue to piece together the

prehistoric puzzle of ancient sites, ancient gods, and solar worship of

the Celtic world. How did worship of the solar gods come to be in a land

with a reputation of seeing so little? A complication in the quest for

answers, says writer and researcher of prehistoric sites of Ireland,

David Halpin, is that the solar gods and goddesses we are familiar with

today came after many of the solar-aligned sites were already

constructed. Halpin says that, unfortunately, after Ireland’s ancient

monuments were constructed, something happened, and the original

builders seemed to have disappeared. When people arrived years later,

they likely associated their own gods with these places. That leaves

many questions unanswered about the genesis of the solar gods – and the

creation of the incredible monuments found across the landscape.

That being said, Halpin notes there are many sites in Ireland which

begin with the word Bal/Baal/Bel (such as the Baltray standing stones,

or Beltany Tops stone circle) which have sunrise and sunset alignments,

and names to suggest they were sites originally dedicated to a sun god.

Belenus/Bel is a sun god often associated with the Baal of the

Fertile Crescent (the region in the Middle East which curves from the

Persian Gulf, through modern-day southern Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Jordan,

Israel and northern Egypt) and Anatolia. In Margaret Anne Cusack’s

examination of sun worship in An Illustrated History of Ireland , she too connects the name Bel, still present today in the Celtic Beltane, to a Phoenician origin.

With the coming of St. Patrick, a missionary credited with converting

Ireland to Christianity in the AD 400s, old gods, solar gods and sun

worship was denounced, and quashed.

St. Patrick is recorded to have said of the sun, “All who adore him

shall unhappily fall into eternal punishment. Woe to its unhappy

worshippers, for punishment awaits them. But we believe in and adore the

true Sun, Christ!”

It was not a complete transition, as belief in the old gods and

elements of solar and nature worship in Ireland can still be seen to

this day.

Gods and Goddesses

In Irish, the sun is given a feminine name, Grian, even as there are

both male and female deities connected with the sun in today’s Celtic

mythology. Perhaps originally there were only solar goddesses, and the

male gods were later attributed as sun gods by their identification with

the Roman Apollo, god of sun, light, and knowledge.

Grian is the winter sun, and her sister or dual nature is Áine, the

summer sun. Áine is the goddess of wealth, with power over crops and

animals, and she is sometimes represented by a red horse.

Followers,

even as recently as 1879, would hold rites in honor of Áine involving

fire and blessings at the the hill of Knockainey ( Cnoc Áine ), County Limerick.

Brighid appears as a member of the Tuatha Dé Danann , a supernatural race containing the main gods of pre-Christian Ireland.

The Tuatha Dé Danann as depicted in John Duncan's "Riders of the Sidhe" (1911). ( Public Domain )

She is a ‘triple goddess’ associated with an early spring equinox,

light, and fire. It is believed she may be a continuation of an

Indo-European dawn goddess. As many of the stone circles across the

country have an alignment at this time of the year, it suggests the

sites may have a female association. Good weather, and an early spring,

would serve the people well, so Brighid’s festival day, Imbolc is

traditionally a time for foretelling or forecasting the weather.

Brighid is celebrated with fire at a festival. (Mike Wright/ CC BY-ND-2.0 )

Other female Celtic gods bear solar traits, such as the British

Sulis, who was worshipped as a life-giving mother at the thermal spring

of Bath. For being a sun-god, her followers seemed to have dealt in the

dark, as about 130 curse tablets wishing misery upon foes, and addressed

to the powerful lady, were found at the sacred spring. Offerings like

money or clothing were left to Sulis at the baths, and her popularity as

an agent of change for worshippers continues among Wicca and Pagan

communities.

Gilt bronze head from the cult statue of Sulis Minerva from the Temple at Bath. (Hchc2009/ CC BY-SA 4.0 )

A skilled and youthful warrior, Lugh (Lug) is also king and savior.

He is sometimes believed to be a lightning/thunder god, or sun god, and

so powerful by nature that mountains are named after him. A member of

the Tuatha Dé Danann , he is linked to many famous legendary

figures, including his son, the ultimate Irish warrior hero Cú Chulainn.

His solar-god status seems to be a Victorian-era connection, as his

name derives from the Proto-Indo-European words “flashing light”. Lugh

was worshiped throughout the Celtic world and was popular among all

classes of people from farmers to kings.

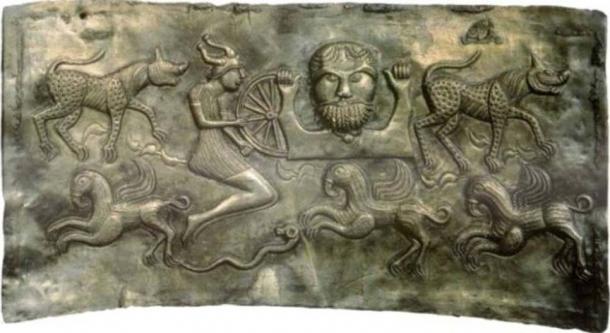

Belenus, the ‘Fair Shining One’, or ‘Shining God’, was a

widely-worshipped ancient solar deity.

Associated with the horse and the

wheel, he rides across the sky in a wild, horse-drawn chariot.

Solar Doorways and Fires for the Gods

Older than the Egyptian pyramids of Giza, older than Stonehenge, Ireland’s Newgrange ( Sí an Bhrú )

has prehistoric roots and a fascinating mythology. The massive monument

in County Meath, and seated near the River Boyne, dates to 3200 BC. It

is identified as a passage tomb; an earthen mound with a long passageway

and chambers, with a stone circle ringing it.

Newgrange at a distance. County Meath, Ireland. (Jimmy Harris/ CC BY 2.0 )

Journalist and astronomer Anthony Murphy told Ancient Origins that

Newgrange contained both cremated and uncremated remains, and today’s

archaeologists, while not prepared to change the description of the site

from ‘passage tomb,’ acknowledge the monument likely had many different

purposes. Rather than simply being a tomb, it is felt that solar

worship could have taken place there, and there’s easy proof to that.

When the sun rises on the shortest day each year, winter solstice,

the illuminating beams shine directly down the long passage, and fill

the inner chamber with light, brilliantly revealing the swirling

carvings on the walls of the chamber – most notably a triple spiral. The

sunlight pours in through a clever roofbox, a purpose-made opening

above the main entrance. Newgrange is one of the very few passage tombs

to feature this special roofbox.

A shaft of light at the Newgrange Passage Tomb (Dentp/ CC BY-SA 4.0 )

Newgrange and the surrounding Boyne monuments in nearby Knowth and

Dowth all feature solar alignments, showing that these beliefs were

strongly-enough held to create adept and amazing astronomical devices

and places of worship. An impressive site, it is imbued with millennia

of folklore. In some Irish myths, the monuments were gates or portals to

lands of the gods, and this is where Cú Chulainn was born.

The Spreading Flames of Protection and Worship

In Meath, a hotbed of prehistoric ritual, and not far from the famous

Royal Hill of Tara are ancient sites of Hill of Uisneach, and Tlachtga

(Hill of Ward).

The Hill of Uisneach is believed in legend to be the site of the

first great Beltane fire to be lit in all of Ireland. Beltane, (held

commonly on May 1, halfway between the spring equinox and the summer

solstice), is one of the four Gaelic seasonal festivals.

World Heritage Ireland writes: “To usher in the first dawn of summer

in May, the Uisneach hearth burned biggest and brightest of all; visible

to over a quarter of Ireland. Hearths were extinguished in every Irish

home and fireplace in the country, in anticipation of a new flame from

Uisneach’s Bealtaine fire. It must have been an extraordinary sight,

with the country plunged into utter darkness ahead of this sacred

festival. Using the flame from Uisneach, fires were then ignited on the

other sacred hills of Ireland. When lit, they created a unique ‘fire

eye’ over the island, ushering in an entire summer of sunshine.”

The bonfire lit to welcome Beltane morning. Edinburgh 2008. ( Public Domain )

Uisneach is steeped in solar mythology, as it is said to be the location where Lugh met his end.

Dagda, leader of the Tuatha Dé Danann was believed to live

at Uisneach and stabled his ‘solar horses’ at the site. Interestingly, a

wheel-shaped enclosure was uncovered here, which concealed two

underground cavities. One was in the shape of a divine mare being

pursued by a galloping stallion.

Winter is Coming

Tlachtga was a powerful druid in Irish mythology, associated with the

Hill of Ward, County Meath, a center of Celtic religious worship over

two thousand years ago. Tlachtga’s father, Mug Ruith was said to fly

across the sky in a flying machine, roth rámach . Such feats, and a very long lifespan, signaled him to be a sun god.

The major ceremony held at Tlachtga was the annual lighting of the

winter fires at Samhain (November 1). This Great Fire Festival signaled

the onset of winter, and these energetic blazes on the hill would

reassure that the approaching time of darkness would be overcome. The

warmth and light of the fire must have felt like a powerful physical

connection to a solar god, and a bolstering of hope in uncertain times

of darkness and cold, wet winds.

A ritual bonfire demonstrates the ancient Celtic way of life. (Martyn Pattison / Beltain Festival at Butser Ancient Farm / CC BY-SA 2.0 )

Because prehistoric dedication to solar gods and worshiping of the

sun is simply, as 19th-century historical writer James Bonwick notes,

“the reverent bowing to the material author of all earthly life,” we

cannot condemn those who admired the sky; those who created such

memorable, shining gods, and the awe-inspiring monuments and megaliths

of ancient Ireland. Indeed, if it made a difference in the island’s

renowned changeable weather, so the better.

The Druidess, oil on canvas, by French painter Alexandre Cabanel (1823–1890) ( Public Domain )

--

Top image: Solar gods were worshiped in prehistoric Ireland. (Public Domain/Deriv)

By Liz Leafloor

No comments:

Post a Comment