The numbers racket is largely gone now in the face of real lottery competition, except that the direct competition can provide a much better payout and that keeps it all alive. Quick research though shows it was going strong until 2000 at least and i would not count it out.

Trust the government to make something like this illegal. Why bother??? It took a particular type to run the numbers, just as it takes a particular type to sell securities as well. All that is also the glue that activates a community of sorts and help to manage hopes and dreams.

The better course is to simply allow it to run along.

The drug trade produces real harm that has to be managed. there we have learned that criminalization actually expanded the industry. Here it is hard to see any harm when worse odds are legal. Even licensing is barely needed as no one is going to pay off on failure and this is an acceptable risk. In our world of legal gambling, let us all have our bookies and number runners and be done with it.

It is low level and addicts will simply out themselves as usual and be banned.

.

How My Mom Paid For My College Tuition By Running The Numbers

Trust the government to make something like this illegal. Why bother??? It took a particular type to run the numbers, just as it takes a particular type to sell securities as well. All that is also the glue that activates a community of sorts and help to manage hopes and dreams.

The better course is to simply allow it to run along.

The drug trade produces real harm that has to be managed. there we have learned that criminalization actually expanded the industry. Here it is hard to see any harm when worse odds are legal. Even licensing is barely needed as no one is going to pay off on failure and this is an acceptable risk. In our world of legal gambling, let us all have our bookies and number runners and be done with it.

It is low level and addicts will simply out themselves as usual and be banned.

.

How My Mom Paid For My College Tuition By Running The Numbers

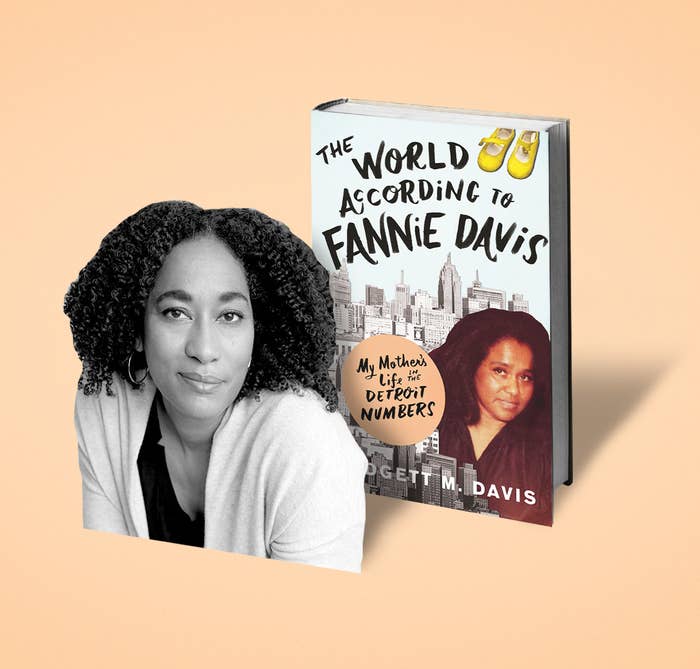

Read this excerpt from BuzzFeed Book Club’s October nonfiction pick The World According to Fannie Davis: My Mother’s Life in the Detroit Numbers.

Bridgett M. Davis

Posted on September 18, 2019, at 10:22 a.m. ET

https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/bridgettdavis/the-world-according-to-fannie-davis-bridgett-m-davis

On a morning like most, I sit beside Mama at the dining room table, eating my bowl of Sugar Frosted Flakes and watching her work. She’s on the telephone, its receiver in the crook of her neck as she records her customer’s three-digit bets in a spiral notebook, repeating each one. The crystal chandelier blazes above.

“Five-four-two for a quarter. Six-nine-three straight for fifty cents. Is this both races, Miss Queenie? Detroit and Pontiac? Okay. Three-eight-eight straight for a quarter. Uh-huh. Four-seven-five straight for fifty cents. One-ten boxed for a dollar.” Mama writes the numbers 110, draws a box around them, hesitates. “You know, I got customers been playing one-ten all week. Yeah, it’s a fancy number. Oh did you? What’d you dream? He was a hunchback? Is that what The Red Devil dream book say it play for? Now that I didn’t know. I know theater plays for one ten. Well, I can take it for a dollar, but since it’s a fancy, I can’t take it for more than that. You understand. What else, Miss Queenie? Six-eight-four for fifty cents boxed, uh-huh. Nine-seven-two straight for a dollar.”

I find comfort in Mama’s voice, in the familiar, rhythmic recitation of numbers. I bring the bowl to my lips and drink the last of the sweetened milk before I rise and kiss Mama’s forehead. She mouths “Bye-bye” as I join my sister Rita, who’s waiting on the porch; together we walk three long blocks to Winterhalter Elementary and Junior High School, passing by the lush Russell Woods Park. I’m a first grader.

In class, I wait in line to show my teacher, Miss Miller, my assignment. We’ve had to color paper petals, cut them out, and paste them onto a picture of a flower. I like mine, as I’ve glued each one just at the base, so that the petals now reach out, into a pop-up flower. Miss Miller looks over my work, gives it one star instead of two, and stops me before I can return to my seat.

“You sure do have a lot of shoes,” she says. Last week, she asked what my father did for a living, and because I knew never to disclose the family business I said, “He doesn’t work.” She asked: “Well, what does your mother do?” I froze. “I’m not sure,” I lied. I knew my mother was in the Numbers, but I also knew not to tell that to anyone. I worried that my vague answer was the wrong one, but I didn’t know a better response. No one had told me yet what I should say.

I knew my mother was in the Numbers, but I also knew not to tell that to anyone.

Now with Miss Miller staring at me I look down at my feet, which are clad in—I still remember—light blue patent leather slip-ons with lace-trimmed buckles. A favorite pair bought to match a brocade ensemble I’ve just worn for Easter. I nod, not knowing what else to do.

“Before you sit down, I want you to name every pair of shoes you have,” she insists. “Go ahead.” There’s no lightness in her voice.

Anxious, I go through a mental inventory of the shoes that line the built-in rack in my bedroom closet. I manage to recall ten pairs in various colors and styles: the black-and-white polka-dotted ones with a bow tie; the buckled ruby-red ones, the salmon-pink lace-ups. ..

“Ten pairs is an awful lot,” says Miss Miller. Her blue eyes fix on me with something I can’t name, but which I’d now call disdain, and she orders me to take my seat.

I can feel my classmates staring at me as I return to my table. Is it wrong to have so many pairs of shoes? Did my mother get them in a bad way?

The next day in class, Miss Miller calls me back to her desk. I can smell the hairspray in her teased blond bouffant. “You didn’t mention you had white shoes,” she snaps.

Indeed, I’m wearing a white version of the same pair I wore the previous day. I feel as though I’ve been caught in a lie, and I know I’ve disappointed my teacher. I worry that I’ll get in trouble. At school, or worse, at home.

“I’m sorry,” I whisper. Miss Miller shakes her head in disgust and dismisses me with a wave of her hand. I return to my desk, trying hard not to look down at my shoes. I am ashamed of them. That evening, I tell Mama what happened. But I wait until after she’s finished taking her customers’ bets and before the day’s winning numbers come out. I’ve already learned that the best time to tell Mama difficult news, something that could get you in trouble, is during that brief, expectant pause in the day. That’s when Mama is least distracted, and still in a good mood.

She listens, and when I confess I forgot to tell Miss Miller about the eleventh pair of shoes, her dark eyes flash with anger. I fear a spanking.

“That’s none of her damn business!” she says. “Who does she think she is?” Before I can feel relief that she’s not mad at me, Mama says, “Get your coat and let’s go.” I do as I’m told. Mama throws on her soft blue leather coat, the color of the Periwinkle crayon in my Crayola box, and together we slide into her new Buick Riviera; are we headed back to school to confront Miss Miller? Thank God no, as Mama heads south, away from Winterhalter Elementary; she soon turns onto Second Avenue, drives to the corner of Lothrop, and parks in front of the New Center building. There sits Saks Fifth Avenue.

We enter through regal double doors and I instantly fall in love with the store’s marble floors, brass elevators, and bright chandeliers. I feel lucky just being here. Mama takes my hand and leads me to the children’s shoe department, where an array of options spreads before us. She points to a pair of yellow patent leather shoes. “Those are pretty,” she says.

Perhaps the saleswoman looks at us askance, given how rare it must have been to see black people inside Detroit’s upscale shops in the sixties, but I don’t remember. What I do remember is how nonchalantly Mama opens her wallet, pulls out a hundred-dollar bill, and pays for the shoes, while the saleswoman looks at her the way Miss Miller looked at me.

When we get home, Mama says, “You’re going to wear these to school tomorrow. And you better tell that damn teacher of yours that you actually have a dozen pairs of shoes, you hear me?” The next day, I wear my brand-new shoes with a matching yellow knit dress. Nervous as I walk up to my teacher’s desk, I announce: “Miss Miller, I have twelve pairs of shoes.” She looks down at my feet and then levels those blue eyes at my face. “Sit down.”

Fannie Davis left Jim Crow Nashville for Detroit in the mid ’50s with an ailing husband and three small children, and figured out how to “make a way out of no way” by building a thriving lottery business that gave her a shot at the American dream.

Miss Miller never says another word to me. I feel her rejection but I’m also relieved; I no longer have to worry about what I wear to school, or feel bad about my nice things. I feel both protected and indulged by Mama. Growing up, that’s how it was for me, and my three older sisters and brother. We lived well thanks to Mama and her Numbers, which inured us from judgment. My mother’s message to black and white folks alike was clear: It’s nobody’s business what I do for my children, nor how I manage to do it. The fact that Mama gave us an unapologetically good life by taking others’ bets on three-digit numbers, collecting their money when they didn’t win, paying their hits when they did, and profiting from the difference, is the secret I’ve carried with me throughout my life. I’ve come to see it as her triumphant Great Migration tale: Fannie Davis left Jim Crow Nashville for Detroit in the mid ’50s with an ailing husband and three small children, and figured out how to “make a way out of no way” by building a thriving lottery business that gave her a shot at the American dream. Her ingenuity and talent and dogged pursuit of happiness made possible our beautiful home, brimming refrigerator, and quality education.

Our job as her children was twofold: to take advantage of every opportunity she created, and to keep safe the family secret. The word illegal was never spoken, but the Numbers were by their nature and design an underground enterprise. We understood this. So my siblings and I followed her edict: Keep your head up and your mouth shut. Be proud and be private.

But as I grew older, our family secret became the paradox of my life. I idolized my mother and loved being her daughter, was especially grateful for the example she’d set. As an adult, I wanted to share with the world her generous nature and keen parenting skills and sharp business know-how. But of course the bravest, badass part of her life had to be kept hush-hush. I considered writing a thinly veiled fictional story, but even that felt too risky. And writing about my mother without mentioning the Numbers would be fruitless. I know because I tried and it didn’t work. Mama and her Numbers were inextricably intertwined. So, I kept quiet.

After Mama died in 1992, my sister Rita briefly took over running the business; but she eventually closed it down and our family’s life in Numbers ended, and with it, the threat of exposure disappeared. For the next two decades, I told no one but my husband what my mother had done for a living. The family secret, a handed-down order, was well in place by the time I was born. It was all I’d known my entire life. I am hardwired not to tell. I can still hear Mama’s voice, hear her warning: “No good can come from running your mouth.”

I believed her. And I didn’t want to betray Mama’s trust, nor dishonor her legacy. I worried that people would judge her, judge us, for her livelihood. Besides, as long as I kept her secret, abided by her rule, I kept her alive in my memory. Telling would be odd, might trigger a betrayal that led to forgetting. I grappled with that odd dissonance for a long time, proud of my mother but unable to brag about her.

I grappled with that odd dissonance for a long time, proud of my mother but unable to brag about her.

Over time, as I began to understand the depth of my loss, my own feelings shifted, and I wanted to tell Mama’s story; this desire grew into a smoldering, yearning urge that got harder and harder to suppress. I felt cheated. As dynamic and trailblazing as she was, I couldn’t brag about her the way friends bragged about their own mothers going back to school to get a PhD, or surviving as divorced single moms or joining the Peace Corps at fifty. Now it was killing me to keep her life’s work a secret, and I compensated by talking about her incessantly, quoting her pithy sayings whenever an opportunity presented itself. I made sure those who hadn’t met her learned via my constant bragging how exceptional she was. If asked, I told people my mother had been “in real estate,” that she managed properties she owned, that her livelihood came from collecting rent—a half-truth. (Little did I know that “being in real estate” was code for being a number runner.)

As more years passed, I began to feel remiss for not telling, guilty of omitting such a crucial fact about my mother’s life. I talked about her less and less because of that guilt, and that saddened me, as I knew that my mother’s work had transformed our family’s lives, kept us going. It felt disrespectful, really, to keep quiet, as though I was dishonoring Mama with my silence. I was who I was because my mother chose to be a number runner, and my own children didn’t even know who their grandmother had been, what she’d accomplished with her life. A secret, good or bad, weighs on you.

And there was this new fear: If I didn’t tell, would I forget what the Numbers were? Grappling with these mixed emotions, for years I topped my New Year’s resolution list with the same goal: “Tell Mama’s story.” But I still couldn’t get past the habit of withholding, or the fear of revelation.

Finally, in the way in which we draw from public figures’ mythic lives for personal inspiration, I convinced myself that if patriarch Joseph P. Kennedy Sr. could allegedly use his early years as a bootlegger to launch his family’s fortune, actions that brought him no recrimination since alcohol became legal anyway, then Mama’s work was analogous. She too engaged in a business practice that eventually became legal.

And so I took a big, scary step: I flew to Detroit, sat at the dining room table across from my aunt Florence, my mother’s remaining sister, who was celebrating her eightieth birthday that year, and nervously asked the one person whose permission I most needed: Would it be okay with her if I wrote about Fannie’s life as a number runner? My aunt’s answer surprised me. “Honey, I’ll help you tell it,” she said. “’Cause what your mama did was unheard of, what she created was something else and folks should know.” And then she smiled. “She made sure you didn’t have to worry about no life in Numbers, so I know you don’t really understand too much. I’ll explain it to you.”

I laughed with relief. She was right. I didn’t understand the intricacies of the Numbers business. Having Aunt Florence’s blessing and her know-how freed me. I started by digging through an old brass trunk filled with my mother’s possessions that I’d kept in storage in Manhattan for many years. I hadn’t looked through this trunk since Mama’s death. Inside, I found a manila envelope filled with nearly a dozen letters that my sister Rita, four years older and the closest sibling to me in age, had written to God. They were composed on pages clearly ripped from the spiral notebooks once ubiquitous in our home, used to record customers’ bets, bills, and payouts. In one letter, my then twelve-year-old sister wrote:

Dear God,

Please don’t let 543 come out tonight. And please take away Mama’s headaches.

Your loving servant, Rita

In another letter, she simply wrote:

Dear God,

Please stop me from worrying.

Thank you, Rita

I’d known that Rita wrote letters to God and stuffed them into the family Bible when we were growing up, but I’d never actually seen one. Reading those letters, all of equal plea, written in a child’s hand, blew open the honed narrative about my mother that I’d burnished over the years. With her number running, she’d pulled off an amazing feat worthy of recognition. But the truth was more complicated, and stark: Mama’s livelihood was risky business, and my sister articulated the stress we all felt from living with that risk. Rita also understood that given the secret nature of our lives, she could only confide in God.

Back then Rita understood what I did not. To maintain our comfort, Mama fought steadily against the threats of fierce competition and wipeouts, but also against exposure and police busts—and thanks to the cash business she was in, armed robberies and break-ins. Rita knew before I did that Mama carried a pistol in her pocketbook, kept another one in her bedroom. Still a child, and the baby of the family, I knew just enough to keep our secret safe; but my sister, a preteen, knew enough to worry about our safety.

Mama’s livelihood was risky business, and my sister articulated the stress we all felt from living with that risk.

And while it was important to keep our secret, it wasn’t at the forefront of my young life. That word secret is so loaded, suggests its country cousin, shame; but I wasn’t ashamed of anything because our family secret wasn’t dark, and my mother acted neither apologetic nor embarrassed. Secrecy was my normal, part of what it meant to be the child of a particular kind of small business owner: you help out, you keep quiet and you either go into the family business one day, or vow to do something else with your life.

Also, while I knew to preserve our secret, I didn’t fully appreciate what could happen if it got out. Yes, Mama could get busted, but I didn’t process what that meant: that our good life would end. No one in our family ever talked about it, but we knew. Mama’s was a cash business and plenty of money was always literally in our midst, yet my siblings and I understood viscerally that our middle-class prosperity was tenuous, always under threat, because Mama’s livelihood was based on a win-or-lose daily gamble. Nowhere was that threat more evident than in our household’s nightly ritual: as dusk fell and we all waited for the day’s winning numbers to come out, a tense silence moved through our home like a nervous prayer. And once it was past 7 p.m. and we knew those three-digit combinations, we took our cues from Mama. Either she looked relieved, or she looked worried. Either she’d been lucky that day, or her customers had been. If she found a big hit by one of her customers, the energy in our household shifted to the solemn yet brisk activity of gathering and counting money, oftentimes large sums of it. Yet Mama never resented her customers’ wins. “People play numbers to hit,” she used to say. “So you can’t be mad when they do. Business is business.”

Each time my mother had a large payout, I didn’t realize she could be wiped out. Despite the “good spell” versus “rough patch” nature of her work, Mama never conveyed a sense of fear or instability. She was a domestic magician with incredible sleight of hand. She made our family’s life appear stable and secure. And so I might’ve been anxious beyond my own understanding, but in my day-to-day world, I believed there was nothing to worry about. I now know that risks were everywhere, coming from different sources, reverberating inward. How hard it must have been to shield us from the vagaries of the business, all run from our home, in full view, where the phones and the doorbell rang constantly and the work of running the Numbers sometimes continued until bedtime. It was risky for Mama to send that “how dare you” message to my first-grade teacher. Doing so could’ve invited Miss Miller’s wrath and retaliation. The year was 1967, mere weeks before Detroit’s uprising, its infamous “race riot.” Racial tensions ran high. Miss Miller could’ve reported to authorities her suspicions about our family’s income. I now think of the risk Mama took that day as a small revolutionary act, just one of many.

My mother gave us a good life at great expense. I thought I knew her skills as a number runner, that she used her facility with numbers, good judge of character, winning personality, and dose of good luck to build and maintain her business for three decades. But I had no idea just how much of a gambler she was, or the kind of psychological work it took to keep our world afloat.

Scariest of all is this: the only way for me to tell Mama’s story is to defy her, by running my mouth. ●

No comments:

Post a Comment