What this maps is the last of the legal slave trade which dragged on into the late nineteenth century. Turns out that the illegal slave trade is sadly alive and well. What actually killed the slave trade was the steady global rise of fiat mony and public supported credit which made slavery too costly.

A proper global financial safety net should completely elimknate most of the remaining illegal slavery or at least prevent parents selling of children. We are still not there but the trend is intact.

Understand that the prime agency for classical slavery has never been understood. It centered on the ocean shipping industry needing a handy source of income. A slave could be captured in one port and then sold in another port, securing the individual against simple escape.

Understand that the prime agency for classical slavery has never been understood. It centered on the ocean shipping industry needing a handy source of income. A slave could be captured in one port and then sold in another port, securing the individual against simple escape.

Now ask a question? just how did these guys make money? You had seasonal plantation crops and minerals. What did they do the rest of the time? We hear about the late slavevships, but what about any other ship? You meet an agent in boston, then sail to a local harbor to pick up a string of captives before sailing for the Bahamas.

All this exclusive to the captain. And no one says a thing. Understand that the indian population collapsed in the americas over two centuries and not just to supply the mines of the DON but also to produce sugar.

Obviously expeditions would harvest any small communities and bring the captives back to the coast. And everyone kept quiet because the govenor was dealing in good faith even then. Stories about mass pandemics were just that and occured rarely and otherwise left no witnesses. our historic events left survivors and witnesses. slave events left a black hole of information. .

The end of self-delusion? Challenging slavery’s heritage in Spain and Catalonia

Adrià Enríquez Àlvaro18 February 2022

5 min read

Photo: Maria Rosa Ferre, Statue of Antonio López y López, Barcelona (CC BY-SA 2.0; cropped image)

History, memory and local heritage are often not compatible. Consider the good number of coastal towns – especially in Andalusia, Catalonia and the Basque Country – from which merchants sailed forth in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries to make their fortune in Spain’s colonies. Such men were celebrated, upon their return, for their investment in railroads, urban, industrial and health infrastructure improvements and artistic movements such as the Catalan Art Nouveau. While scholars know that a great portion of this capital was gained through the institution of slavery, there has been a disgraceful silence about this in official discourse and popular memory. Narratives about Catalan and Spanish participation in the slave trade, long neglected, are now gradually starting to emerge. The examples of three Catalan municipalities – Barcelona, Vilanova i la Geltrú and Sitges – can shed light on a potential change in public discourse in Spain more generally.

Spanish and Catalan participation in the slave trade

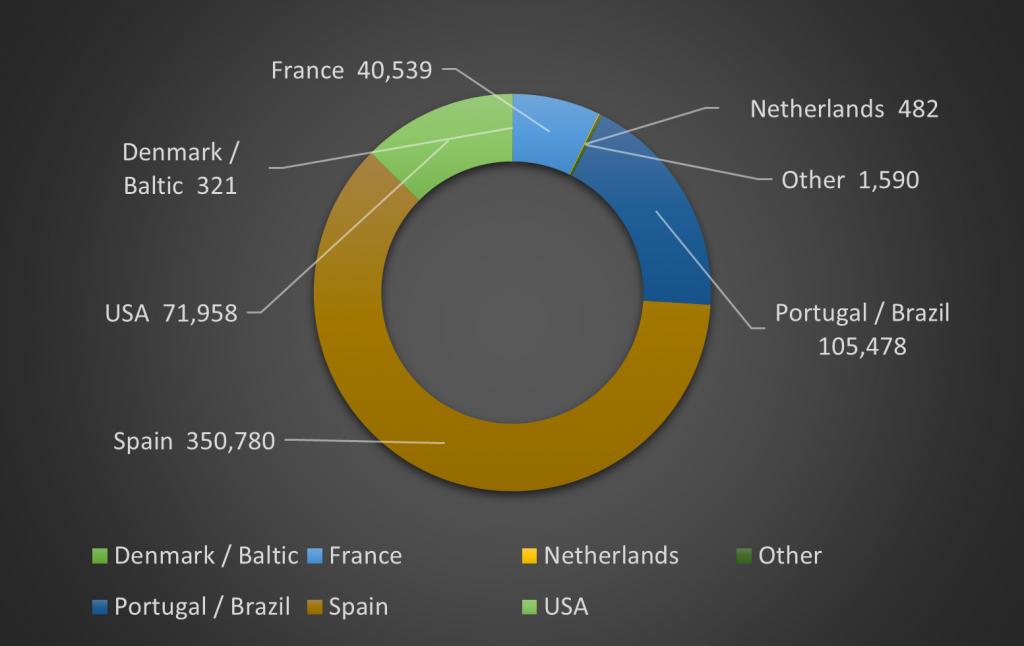

In 1817 Spain signed a treaty with the United Kingdom that abolished the transatlantic slave trade. However, as can be seen in Figure 1, the arrival of new slaves to Spanish America, especially Cuba and Puerto Rico, continued until very late in the nineteenth century. ‘Spanish America’ here is defined as all territories that were part of the Spanish Crown before and after independence. In the period after the trade was abolished, Cuba alone took in more than 550,000 slaves who had been shipped illegally. Most of the enslaved people were used as labour on sugar plantations, where they suffered extremely violent treatment and survived on average less than 10 years after arrival. Cuba abolished slavery only in 1886; it was the last colony to do so.

Figure 1: Total number of African slaves disembarked in Spanish America since 1789. The reference point of 1789 is used because that year Charles IV completely liberalised the slave trade in Spain. Data from The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database (accessed January 2022).

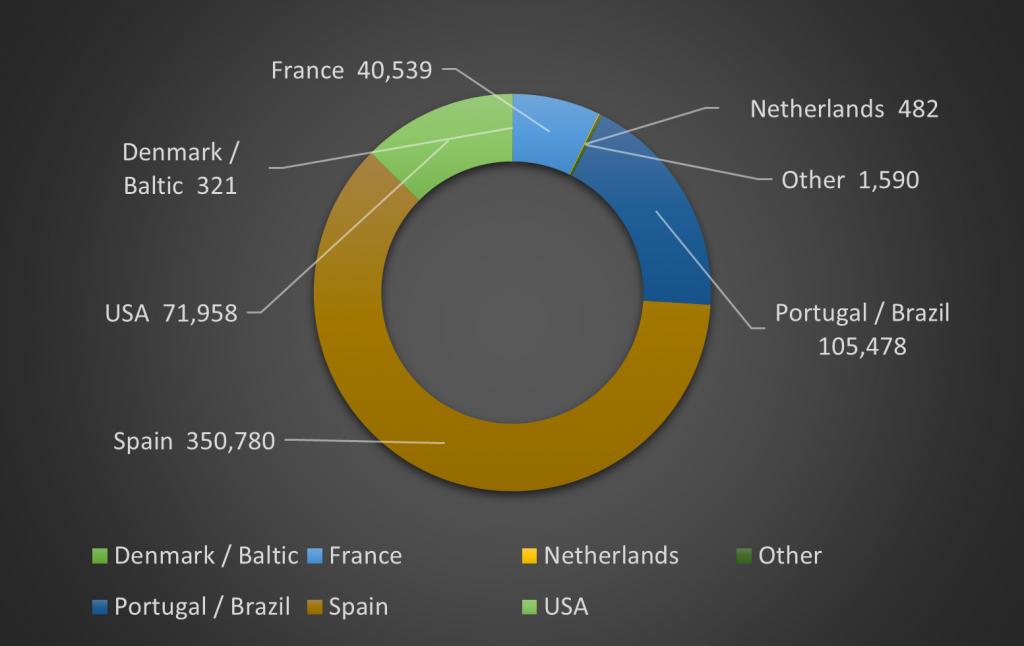

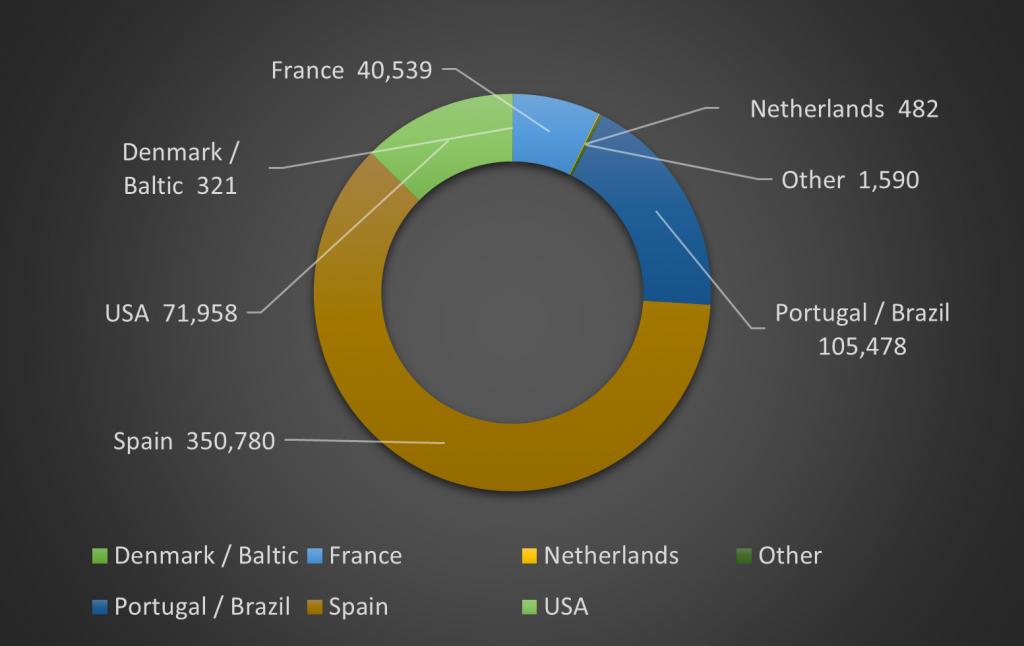

After the abolition of the slave trade by the UK and the USA, most of the transatlantic slave traders that arrived in Cuba were Spanish based, as seen in Figure 2. Although the trade officially was abolished, the purchase of enslaved people in Africa by Spanish and Catalan traffickers continued, and in fact increased. Systemic corruption of civil servants and authorities in Cuba allowed the massive introduction of new African slaves. Furthermore, Catalan participation in the illegal slave trade was crucial in the colonial system of the Caribbean Spanish Empire, which provided a continuous labour force to different plantations and production systems held by different Spanish agents. Profits from enslavement and exploitation of African populations were the reality in the colonies. The Spanish state’s official moral stance against the slave trade was a facade.

Figure 2: Number of slaves disembarked in Cuba between 1817 and the last slave ship arrival in 1866, by flag/nationality of carrying ship. Data from The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database (accessed January 2022).

Official memory and popular pressure

As mentioned above, many Catalan towns commemorate merchants who made their fortunes ‘in the Americas’. They are honoured with street names, statues, museums, guided tours and even special holidays. Usually, not a single word is lost on the origin of much of their wealth: Cuba in the nineteenth century was the world’s most profitable colony, thanks to its sugar, rum, coffee and tobacco production based on slave labour. After the long silence, however, some local developments today perhaps indicate a new type of memory in Catalonia, of the thousands of enslaved Africans who sustained the colonial world.

In March 2018, a statue of the Marquis of Comillas, Antonio López y López, was removed from public display in Barcelona. One of the city’s wealthiest residents of the time, Antonio López built his fortune in the 1830s and 1840s introducing slaves from the illegal transatlantic trade to the legal slave market in Cuba using his fleet. The city council decided to take this action after several demonstrations by Afro-descendant and Latin American populations against Spain’s colonial past. Since then, new public history activities have started to be held in the city, relating to slavery and memory.

In October 2020, the city council of Vilanova i la Geltrú inaugurated a memorial programme to reflect on the town’s relationship with slavery in America. An initial study on memory, history and heritage identified public locations that were connected with slavery as an institution. Further initiatives will propose a possible renaming of streets, the contextualisation of public places and monuments, a new official discourse on the colonial past and new educational programmes on the history of the city. The trigger for this new awareness of the past was a political action in 2016 that included defacing the main statue of the city – the merchant Josep Tomàs Ventosa i Soler – with red paint.

In January 2022, the municipality of Sitges held a conference on slavery’s legacy in several Catalan towns, including itself. While the actions taken by neighbouring Vilanova had already influenced Sitges to start its own memorial programme and consider changing some street names, popular pressure increased in June 2020 after the assassination of George Floyd. A demonstration organised by the town’s Afro-descendant community in front of the statue of Facundo Bacardí – one of the world’s best-known rum producers, who was born in Sitges – honoured the Black Lives Matter movement and criticised the racism that the community experiences daily in Spain.

An end to self-delusion?

While the actions taken by different localities in Catalonia following popular pressure might begin to change the official treatment of history and heritage, Spain’s colonial and slavery past remains unnoticed for most of the population. Public historical discourse in Spain has neglected slavery while exoticising colonial America as a space of social mobility and enrichment. More public history and disclosure work is needed.

Without fully facing its past, Spain will have difficulty recognising the racial discrimination that continues to exist. Today’s amnesia must be corrected to honour the lives of the enslaved and their descendants. Acknowledging the violence that they suffered and recovering their rights to be remembered can be a good start toward greater awareness of the colonial system and its social effects that persist until today.

No comments:

Post a Comment