I do not know what is out there, but centuries of documents need to be curated and electronically copied using AI tech in order to shift out real grains to be better investigated.

most are held in old estates and maintenance is far from assured. Of course the technology for reaching back in time to capture such output is coming along as well and that ends the problem of lost writings.

We are not there yet, but we can scour our old libraries in the now.

The 420-year-search for Shakespeare's lost play

7th November 2023, 05:00 PST

Share

By Zaria GorvettFeatures correspondent@ZariaGorvett

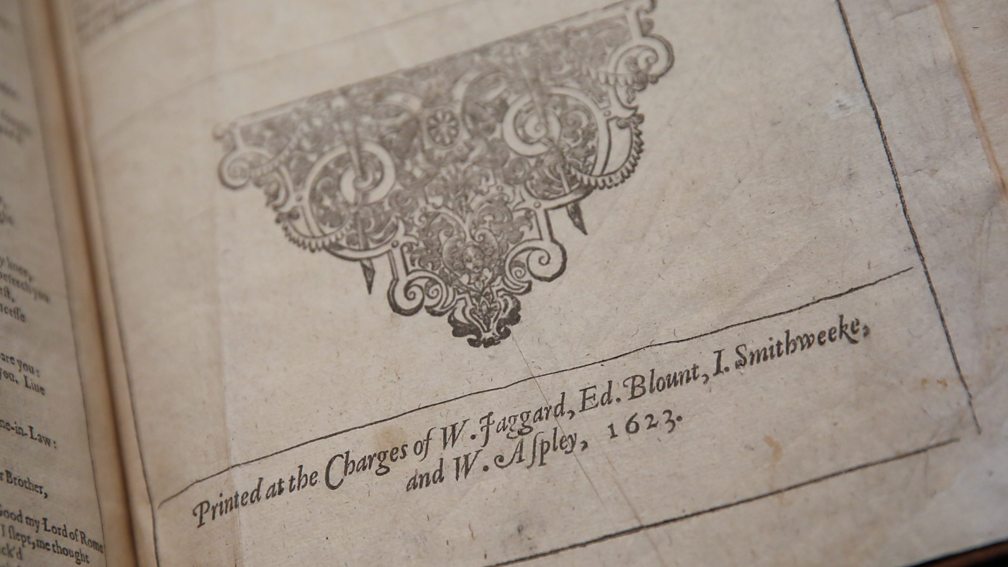

Getty ImagesThe First Folio established canon and is held responsible for preserving Shakespeare’s legacy (Credit: Getty Images)

https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20231107-the-420-year-search-for-shakespeares-lost-play

To celebrate the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare's First Folio, BBC Future investigates a mysterious vanishing – a play that hasn't been seen for centuries.

In 1953, Solomon Pottesman held what appeared to be an ordinary, albeit very old, manuscript in his hands. As he carefully undid the wrappings on "Certaine sermons", which was published in 1637, two leaves of tattered parchment fell out.

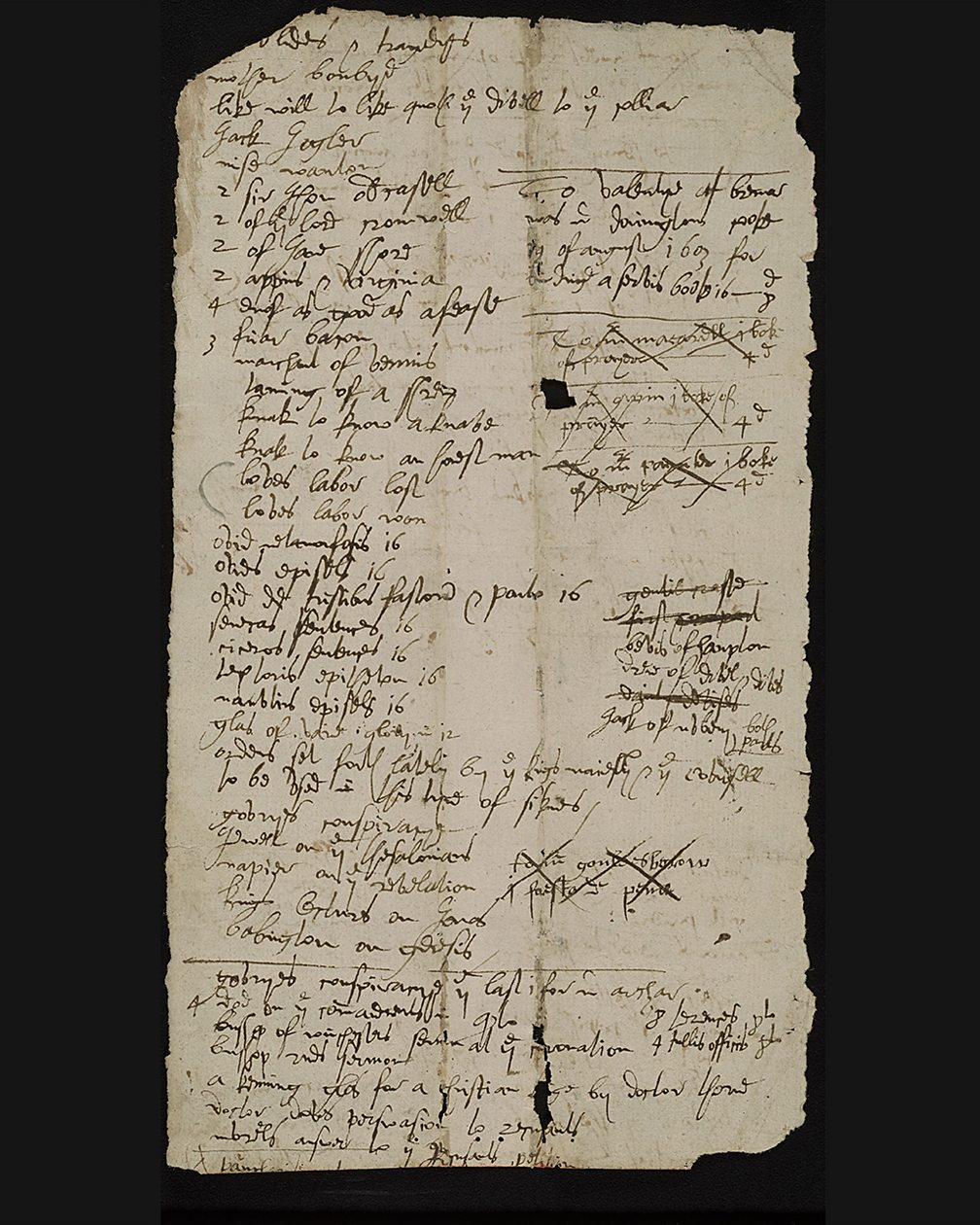

Pottesman, an eccentric and prolific book collector known in the trade as "Inky", immediately knew that something exciting was afoot. The yellowed pages were scribbled from edge to edge with florid, archaic handwriting – rows of book titles, with crossings out and lines drawn across whole sections, as though the writer were making an informal list. On closer inspection, that is exactly what it turned out to be: a casual inventory of works for sale by a stationery shop in Elizabethan London. Though sheer luck, these venerable notes had ended up fortifying the spine of a volume of religious lectures, where they remained for over three centuries.

"This [paper] was just junk," says Cait Coker, curator of rare books and manuscripts at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. "And then someone else would have used it, not thinking about it whatsoever, and that would have been the bones of a new book." But the frayed pages don't just provide a window to the mind of an Elizabethan bookseller. They also hint at a literary mystery – one that has been gripping academics for generations. Around halfway down the list, it reads: "… Loves labor lost… Loves labor won [sic]". This is peculiar, because while the former item is a popular play by William Shakespeare, performed in theatres across the globe to this day, the latter is totally unknown. In fact, it's not supposed to have ever existed.

How did this enigmatic work end up being sold by a bookshop? Could it really be possible that a play by the man widely considered to be the greatest ever dramatist and writer in the English language, had gone missing? This is a story of antique manuscripts, scattered hints, heated debates, accidental discoveries – and the lingering secrets of William Shakespeare.

"This [list] was something that was never meant to survive – it was someone's daily note," says Coker. "And it's the crazy random happenstance of it ending up in a book that survives for hundreds of years, and then the person who is taking it apart in the 1950s doing the double take to look closely and recognise what this piece of paper is," she says.

University of Illinois at Urbana-ChampaignLove's Labour's Won has been missing since it was mentioned in 1603 (Credit: The Rare Book & Manuscript Library, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign)

A precarious situation

On 25 March 1616, Shakespeare signed an important legal document. Though it explained that he was "in perfect health & memorie, god be praysed", he was making his last will. Among a number of oddly specific bequests – including that his wife Anne Hathaway should have their "second best" bed – he left money for his closest companions to buy rings in his memory. One month later, he was dead.

Two of these friends would later prove central to the preservation of Shakespeare's legacy: John Heminge and Henry Condell, his colleagues at the acting company The King's Men. Though Shakespeare's plays were already popular when he died – enough so that he had bitter rivals – it's thought that if it weren't for the actions of these comrades, many of his works may have vanished forever.

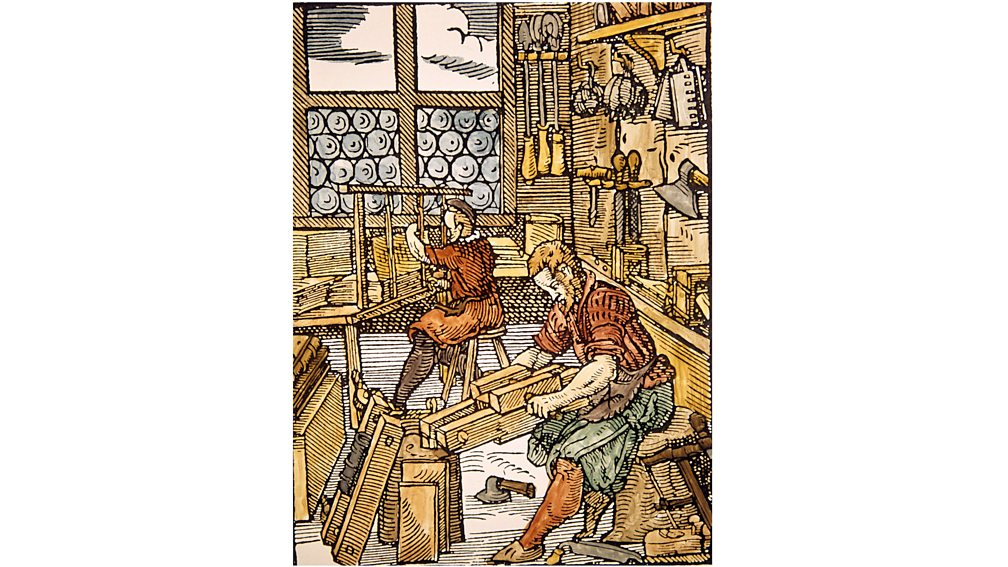

In the Elizabethan era, plays ran the gauntlet of numerous existential threats. For one thing, paper was expensive; so much so that any written manuscript, including a playscript by a literary genius, could eventually end up being recycled for an entirely different purpose. This remained true for centuries. In the book Elizabethan Handwriting, 1500-1650: A Manual, the authors relate the story of an 18th-Century antiquarian who stored a pile of precious manuscripts in his kitchen, only to discover later that many had been used by the cook to line baking dishes.

In fact, despite Shakespeare's fame and influence, the only remaining samples of his handwriting, other than his signatures, are notes on a single collaborative work The Booke of Sir Thomas Moore. And though by the time he died around half of Shakespeare's plays had been published, this was no guarantee of survival. The works were issued as "quartos" – a kind of manuscript made of simple folded paper, often compared to the modern paperback.

These relatively cheap books were notoriously disposable. They were easily damaged or lost, sometimes contained pirated material, and often didn't even mention their author by name. "They're not really in a form that you would say, 'Oh, these are for keeps – these are to look back on in 20 years' time,'" says Emma Smith, professor of Shakespeare studies at the University of Oxford.

Getty ImagesEven plays that had been published as quartos before the First Folio have been preserved by it – each version could vary by hundreds of lines (Credit: Getty Images)

In all, an estimated 3,000 Elizabethan plays have gone missing.

For Shakespeare, the turning point came in November 1623, when Heminge and Condell released his First Folio. This comprehensive tome documented "Mr William Shakespeare's Comedies, Histories & Tragedies, published according to True Originall Copies." It included 36 plays, 18 of which had never appeared in print before – works that they had painstakingly pieced together using their exclusive access to original prompt books, scripts and notes. Without this intervention, All's Well That Ends Well, The Taming of the Shrew, and Macbeth would have disappeared centuries ago. (To celebrate the 400th anniversary of the First Folio, read more from the BBC about the impact Shakespeare has had on our everyday language.)

But there were notable absences.

A handful of clues

As it happens, Love's Labour's Won is not the only Shakespearian play thought to have vanished.

In May 1613, Shakespeare's colleague Heminge (sometimes spelt Heminges) received "twentie powndes" from the Treasurer of the Chamber to King James I. It was for "presentinge sixe severall playes" – one of which was listed as "Cardenno". Then just two months later, the same title appears in the treasurer's records again – this time they've been asked to perform it in front of a visiting duke.

Fast-forward to 1653, and another bookseller's list comes into the picture: among several plays that they are publishing is The History of Cardenio – a play by John Fletcher and William Shakespeare. "And that's quite plausible, because we already know that Shakespeare collaborated with John Fletcher on two other plays," says Gary Taylor, professor of English at Florida State University. However, the play then vanishes from the record – and this is where its history becomes murkier.

Seventy-four years on, in 1727, and there's a new play premiering at the Covent Garden Playhouse in London. It has an original name, but according to printed editions, "Double Falsehood" was revised and adapted from a play by Shakespeare. There's even a neat story to explain how this happened: the author managed to acquire three early manuscripts of The History of Cardenio, which were reportedly stored at the theatre where it was performed. Alas, a fire destroyed the building and its library in 1808, so this has never been corroborated.

AlamyIn Elizabethan times, paper was often more valuable than what was written on it – and this included the words of Shakespeare (Credit: Alamy)

The plot of The History of Cardenio remains largely unknown to this day. Based on the title and fashions of the Elizabethan era, many experts believe it borrowed heavily from the Spanish novel Don Quixote – which was first translated into English just a year before Shakespeare's performance in front of King James I. But for centuries, there has been one nagging question on the minds of those who have studied this lost play: is Double Falsehood really based on Shakespeare – or is it an imposter?

Taylor explains that while some material was clearly added in the 18th Century, other parts of this work seem older or more obviously Shakespearean. One example is the line "Not but itself can be in parallel", which Taylor believes is simply too absurd to have been written by anyone other than the Bard himself. Armed with a comprehensive knowledge of these subtleties, Taylor has devoted 20 years of his career to attempting to reconstruct Shakespeare's version as closely as possible – simply splicing out any material that doesn't seem right.

Though Taylor predicts that most of the original play is no longer available to us, it has experienced a kind of afterlife in its many reincarnations. His version of the play was performed in 2012, hundreds of years after it vanished.

However, in the case of Love's Labour's Won, the losses are on another scale altogether.

A deep void

There are very few known facts about Shakespeare's most mysterious play – primarily, who wrote it and its title. What the plot was, who the characters were, whether there were songs involved or a shocking twist at the end… these things are entirely blank. "It's a sort of wide open, you know, it's like a big vacuum," says Taylor.

Though Love's Labour's Won has only gained traction as a possible lost play since the 1950s, the title was first mentioned many centuries earlier. In 1598, a clergyman and schoolmaster – who was born just a year before Shakespeare – included it on his list of recommended comedies.

Getty ImagesThe portrait of Shakespeare in the First Folio is thought to be a good likeness, since it was approved by two of his closest friends (Credit: Getty Images)

Based on this information, it's thought that Love's Labour's Won was written in the mid-1590s. This, in turn, would mean the play was most likely staged at The Theatre – a playhouse in Elizabethan-east-London's "suburbs of sin" which preceded the famous Globe Theatre, built by Shakespeare's acting company.

Finally, though it's not known for certain, many experts believe that Love's Labour's Won would make a logical sequel to Love's Labour's Lost – a comedy about four young men who swear off women, only to accidentally fall in love.

"It's important for us to remember that Shakespeare's generation, that's the beginning of the modern entertainment industry as a commercial entity," says Taylor. Many concepts that are familiar to us now – such as the idea of sequels to popular pieces of drama – have their roots in the theatre business of late-16th-Century England.

There were already many sequels around at the time, which often had little to do with the original except the title. The stationer selling Love's Labour's Won also had plays by other authors on his list, including two which seem to be related. It's not known who wrote "A Knack to Know a Knave" or "A Knack to Know an Honest Man", but the former – performed in 1593 – was extremely popular. The latter appeared just a year later, and though it had little in common with its predecessor, it is thought to have attempted to capitalise on this success (though that time it didn't work.)

In Taylor's view, the disappearance of certain plays says little about their quality. "I don't think it means that they're inferior in any way," he says. In fact, one idea is that printed copies of Love's Labour's Won may have been so well liked that they were read to pieces. Meanwhile, the repeat performances of The History of Cardenio at King James I's royal court hints that it was a theatrical triumph, he says.

AlamyShakespeare worked for the theatre company The King's Men, previously known as the Lord Chamberlain's Men (Credit: Alamy)

However, there are other ideas.

In the aftermath of Pottesman's discovery of parchment referencing Love's Labour's Won, academics began a fierce debate over its implications. And though most agreed that it likely represented a lost work, at the other end of the spectrum, some suggested that the play may be a mere phantom – it never existed, and found its way into our imaginations by pure accident. In one scenario, the title was coined as an alternative for the comedy Much Ado About Nothing – perhaps because of the neat way the play's plot arc fitted the title, or because of the pleasant symmetry of having a sequel to Love's Labour's Lost.

But if Love's Labour's Won did once exist – and if it was indeed printed – is it possible that it might turn up one day?

A surprising discovery

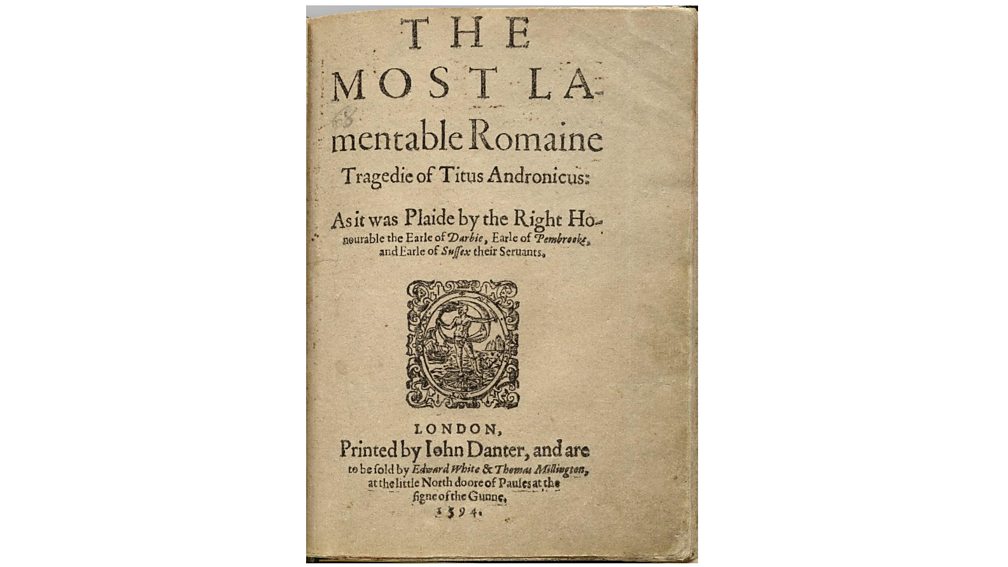

At the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington DC is a handsome black book. With a leather cover and gold detailing, if you open its covers there's a surprise: the text is wrapped up in two 18th-Century adverts for lottery tickets. This unusual volume is the only known copy of the first edition of Shakespeare's bloodiest play, Titus Andronicus.

For centuries, this play, published in 1594 – and introduced on the title page as "The most lamentable Romaine tragedie of Titus Andronicus" – was thought to be lost. That was until one day in 1904, when a postal clerk in Malmö, Sweden, saw a newspaper article about the sale of an early English Bible which had fetched a considerable sum of money. He immediately thought of the battered old family heirloom in his library, a quarto of Titus Andronicus which just so happened to have been bound – long after it was published – into a pair of old lottery adverts. Eventually, he sold the book. The first ever published work by Shakespeare had been rediscovered.

AlamyThere are 14 deaths in Shakespeare’s play Titus Andronicus, which was partially rediscovered in 1904 (Credit: Alamy)

It is serendipitous breakthroughs like this that give Taylor hope for Love's Labour's Won – if one rare Shakespeare book could still be lurking in someone's house undiscovered, hundreds of years after it was published, it might happen again. In fact, he suggests that it's not at all unlikely.

"We're constantly finding new stuff in, you know, in private collections. Libraries that haven't been fully catalogued," says Taylor. Take the recent discovery of a Tudor warrant book in the British National Archives, which has revealed grisly instructions for Anne Boleyn's execution. Taylor points out that she's one of the most written-about people of all time – who, he says, has been called not only Anne of 1,000 Days but Anne of 1,000 Books – and yet, new documents and evidence is still being uncovered.

"If Love's Labour's Won was printed, it's very extraordinary that we haven't found any copy of it yet. So that's most definitely one to look out for," says Smith.

Taylor, Smith and Coker all fully expect that one day in the future, someone, somewhere, will stumble upon a tattered old book – perhaps in a dark, forgotten corner of a museum, or a mysterious trunk in an attic. They will stoop down, blow the dust off its well-worn pages, and read the following words: "Love's Labour's Won, a comedy by Willam Shakespeare". Until then, we can only wait.

--

No comments:

Post a Comment