Understanding That each soul choses his life experiences before entering this life experience makes the whole implied problem go away.

That is never taught though.

The story of Job is a powerful teaching tool. Many of the individual parts of the Bible are equally important as teaching tools and are often this subtle as well.

Many have studied these words and have been led to devout faith.

The Impatience of Job

The story is perfect for our harrowing times. But we’ve been reading it all wrong.

MARCH 13, 20227:00 PM

Photo illustration by Natalie Matthews-Ramo/Slate. Images by ImagineGolf/Getty Images Plus and Unsplash.

https://slate.com/human-interest/2022/03/job-torah-story-despair-alternative-war-democracy-climate-apocalypse.html?

No one has ever known quite what to make of Job.

The title character of the Book of Job is a confounding figure for Christians, Muslims, Jews, and those of any faith who have tried to incorporate the story over millennia. The tale goes like this: Job is a perfectly righteous and God-fearing man whose good deeds have brought him prosperity—children, an estate, good health. But then God enters a wager with a member of the Heavenly Host, haSatan (“the Adversary”), who claims he can make even goodly Job curse the deity. Soon, Job’s servants are killed. His children are killed. He is afflicted with painful boils, finding only mild relief when he gouges them with a potsherd. His life is a waking nightmare. But he refuses to curse God for what has befallen him.

That is, until he debates three of his pious friends, telling them that the logic of religion no longer makes sense to him. If God rewards good and punishes evil, how can one explain what’s happened to him, and to the countless others in creation who suffer for no discernible reason?

The friends say over and over that there must be some sin that Job or his family committed, for God is both morally good and fully omnipotent. With each passive-aggressive accusation from one of his ostensible comrades, Job inches closer and closer to outright blasphemy.

Then the story takes a strange and mysterious turn that consumes religious scholars still.

These days, countless people are experiencing agony on par with that of the biblical Job: An awful war is carrying with it a terrifying nuclear threat; a plague rages; liberal democracy seems to barely cling to life; and, as we corrupt the climate on which our species depends, legions die drowning, burning, or running. If there is a God who loves humanity, He’s showing it in the most mysterious of ways.

Religious people who wait for a messiah may soothe themselves by believing that divine intervention can bring about an end to mortal horrors, and that the pious will eventually ascend to a state of eternal existence. But for secular types—including agnostic Jews like me—who find themselves concerned about the state of the world, both reform and revolt seem impossible routes out of all of humanity’s messes. If it all keeps getting worse, what’s the point of anything? It’s hard to measure pessimism, but there are indications that it’s on the rise, at least in America: Polls suggest pessimistic views have exploded in the past 20 years, and, even before COVID, nearly a third of Americans believed an apocalyptic event would occur in their lifetime.

Lucky for us, there’s an ancient text that offers guidance on how to navigate the pain that lies before us, and how to start rebuilding in the ruins. It’s called the Book of Job. We just haven’t been reading it right.

The most vexing part of Job’s story—after his servants and children die, after the boils, after the debates—comes when Job challenges God to explain Himself in the mode of an ancient Near Eastern lawsuit. The deity appears and, though He declines to explain why He does anything (He prefers to boast of His vast power and inscrutable planning), He praises Job for speaking “in honesty” and condemns the Scripture-quoting pals for not doing the same.

Job then utters a few enigmatic lines of Hebrew that scholars have struggled to translate for millennia: “al kayn em’as / v’nikham’ti al afar v’eyfer.”

The King James Version gives those lines as “Wherefore I abhor myself / and repent in dust and ashes.” Historically, most other versions stab at something similar—though, as we will see, modern scholarship suggests some very different alternatives.

Whatever Job says, it seems to work: In an abrupt epilogue, we see Job restored to his former comfort and glory. Many analysts think the happy ending was added to an initial core text that lacked such comfort. But even if you accept it as part of the story, it’s unsettlingly cryptic. We are not told why Job is rewarded, whether his reward was divinely given, or what scars the episode has left upon him. We are merely told that he’s materially back to something resembling what he had before.

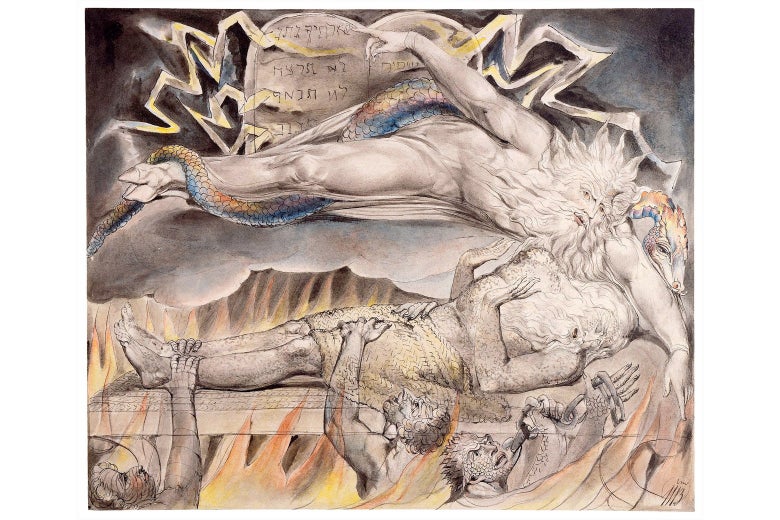

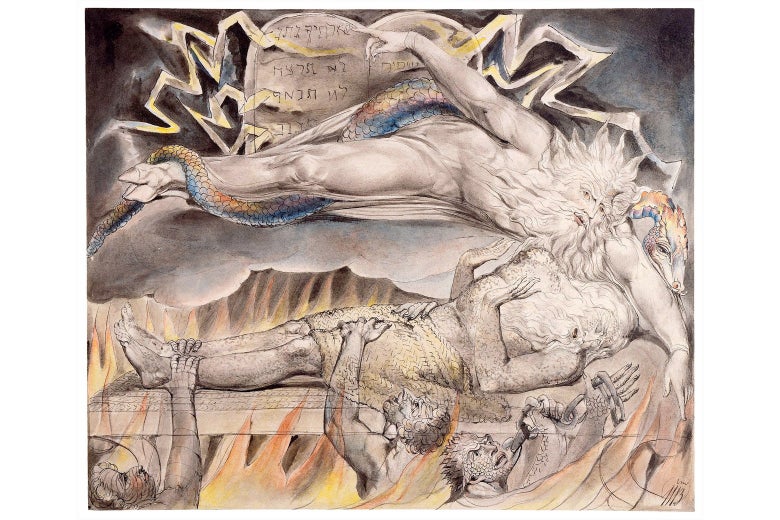

Job’s Evil Dreams, from the Butts set, 1805–06. William Blake/Wikipedia

If no one ever knew what to make of Job, Jews were first among them. Rabbis of the Talmud wrung their hands and tugged their beards over his story. They feuded over who he was, where he fit in the biblical narrative, and what lessons we were to derive from his tale. Though Jews have suffered throughout our history, our traditional texts emphasize that suffering is a punishment from God, not an invigorating step toward spiritual clarity in the Christian mode. As documented in Mark Larrimore’s The Book of Job: A Biography, the rabbis who wrote the Talmud and started formalizing the liturgy in the early part of the first millennium C.E. threw up their hands in defeat to an extent, not knowing what to do with this alarming character, fascinating though he may be.

Early Christians, on the other hand, embraced the Job story as a tale about the redemptive and edifying power of pain in the struggle to cleanse oneself of sin—a core tenet of the Christian faith. Telling someone they had the “patience of Job” was high praise.

But early Christians also connected the Book of Job to another pillar of their system: the apocalypse. The most influential pre-modern Christian writer on Job, the sixth century’s Pope Gregory I, argued that the character’s lamentations should make us excited about the end of days. Won’t it be lovely when this awful, fallen world will finally be destroyed and Jesus can bring about an age of delight for the deserving?

With all due respect to the rabbis and popes of old, I think they were all wrong about Job. And I’m not alone.

I didn’t know about any of this stuff until half a decade ago. When it came to God, I was—and remain—agnostic, and I also had virtually no background with the Bible. Opening up a copy of the Good Book never brought anything but confusion and boredom. I had a vague notion that Job was a story about a guy who suffered (my introduction to him came from his mention in the Smashing Pumpkins’ ’90s hit “Bullet With Butterfly Wings”), but that was about it.

Atheism is, as it turns out, no impediment to the power of the Joban text. It’s a work of ancient poetry as beautiful and enlightening to a secular reader as The Odyssey or Journey to the West.

If you’re skeptical, believe me—I was with you. I was raised as a Jew in the Reform movement, the biggest Jewish religious tendency in America and one attractively lax in doctrine. I went to a Sunday school program at my local synagogue, where I learned some basic Hebrew and had a bar mitzvah ceremony at age 13. I dropped out of organized Jewish life as a teenager. With the exception of a free 18-day trip to Israel in college, I spent nearly 20 years of my life hardly ever thinking about being Jewish.

But a weird thing happened to me, and many Jewish Americans, after Donald Trump’s election. The siren that sounded most clearly in my head was a warning about bigotry against Muslims. Trump’s clear-cut advocacy for official action against them on the basis of religion and ethnicity weighed on me most heavily among his campaign’s evils. How could I not fight against ethno-religious hatred? Wasn’t I a Jew?

I resolved to understand who Jews were to Muslims now. In 2017, I took a two-week solo trip to Israel and the West Bank, sometimes traveling with guides (mostly Palestinian, a few Israelis), sometimes on my own. I’ve written elsewhere about the details of that voyage, but suffice it to say that it was one of the major turning points in my life. The building and maintenance of Israel had been central to every Jewish institution I’d been a part of, as well as to my own family’s history. Abruptly and painfully, I got a glimpse of the moral cost. Nothing is quite the same for a Jew who speaks frankly with a Palestinian about the death and displacement of the region’s Arab population that made—and make—the Zionist movement’s goals realizable. What remained of my old Jewish identity was burned down. Rather than wallow in its ashes, I felt compelled to build a new one.

There’s something revolutionary in the mysterious final words Job lobs at God, something that was buried in mistranslation.

I realize I am far from the only Jewish millennial who has seen truths about Israel and decided to run headlong into making political statements with the prefix “as a Jew.” Indeed, this has become a tendency so common in recent years as to become a cliché. And, as it turned out, newfound identification, education, and outrage still didn’t make me feel empowered to meaningfully improve any lives, let alone my own. Though I learned everything I could about Israel and the Palestinians, I found neither solace nor a path to justice. On the contrary, I mostly found reasons to lose faith in the future: All the wisest experts could offer was an admission that there were no good options—and that the worst of them were the most likely to come true.

By the end of 2017, what felt like an ongoing societal collapse compounded various personal problems and led to the most abysmal depression of my life. Despair called; it was quite hard to find a reason to keep going. Screw it, I thought. Let’s see if God has anything to offer.

I started going to synagogue. I started studying the Hebrew Bible—the Torah—first in English and then in halting Hebrew.

I started reading Job.

The first time I read it all the way through in English, I could barely make out what was happening in the plot. That’s not surprising. If modern scholarship is right, the ancient scribes may have accidentally placed sections of the text out of order in the canonical version; even they, it seems, were thrown off by Job’s notoriously obscure verbiage. But as anyone who’s read it in any tongue can tell you, that doesn’t stop you from being awed by its imagery and immediacy.

These lines from the 28th chapter struck me in particular, as they had many before me:

But whence does wisdom come

And what is the site of understanding?

It is hidden from the eyes of the living

Concealed from the birds of the sky

Even though I’d later learn the passage was likely put in the wrong place, the words stirred me. I knew that, many centuries ago, there was a poet who understood what it was like to feel completely lost.

Edward L. Greenstein’s astounding recent translation taught me that Job’s suffering is only half the story. It’s not even the most important half. Greenstein’s version does not rob readers of the comfort that comes from sympathizing with Job. But it also exhorts us to rebellion against power and received wisdom.

Greenstein points out that a huge portion of what looks like Job praising God throughout the text may be meant as the opposite: Job sarcastically riffing on existing Bible passages, using God’s words to point out how much He has to answer for. Most importantly, Greenstein argues, there’s something revolutionary in the mysterious final words Job lobs at God, something that was buried in mistranslation.

In the professor’s eyes, various words were misunderstood, and the “dust and ashes” phrase was intended as a direct quote from a source no less venerable than Abraham, in the Genesis story of Sodom and Gomorrah. In that one, Abraham has the audacity to argue with God on behalf of the people whom He will smite; however, Abraham is deferential, referring to himself, a mortal human, as afar v’eyfer—dust and ashes. It is the only other time the phrase appears in the Hebrew Bible.

So, Greenstein says, Job’s final words to God should be read as follows:

That is why I am fed up:

I take pity on “dust and ashes” [humanity]!

Remember, for this statement, God praises Job’s honesty.

The deity does not give any logic for mortal suffering. Indeed, He denounces Job’s friends who say there is any logic that a human could understand. God is not praising Job’s ability to suffer and repent. He’s praising him for speaking the truth about how awful life is.

Maybe the moral of Job is this: If God won’t create just circumstances, then we have to. As we do, Job’s honesty—in the face of both a harsh, collapsing world and the kinds of ignorant devotion that worsen it—must be our guiding force.

The Talmudic rabbis offered a dizzying array of guesses about when Job took place. Maybe the titular figure was a contemporary of Abraham? Or Moses? Or King David? Some post-Talmudic interpreters have even said we should read the story as the final part of the biblical narrative—the exclamation point ending the age of humanity in which God spoke to us. I love this notion. Perhaps Job made an argument so airtight that God, embarrassed, ceased talking to humans altogether.

Be that as it may, when God rebukes Job, He speaks at length about the horrifying majesty of the natural world He created. He says that humanity lives in fear of the beasts and the seasons—a relatable sentiment today, to be sure. But it is also a privilege to witness it at all, the text implies: We have been given life and consciousness. We can experience creation. Even if our joys are few, we get to have them. Even if our pains are many, well, we get to have them, too.

That’s the other lesson of Job, the implicit one: This is all we’ve got, and it has to be worth it. Crucially, Job doesn’t kill himself. He curses the day he was born, but he doesn’t bring about the day of his death. He chooses to believe that continued existence is preferable to its opposite.

In the face of all that appears to be in front of the world today, amid all the calamities we are hurtling toward or already enduring, I’ve found no choice but to share Job’s outraged honesty. Job provides a framework for why it’s worth it to keep going.

Absent the book’s likely tacked-on epilogue, the Book of Job teaches that there is no final victory, no ultimate divine deliverance. As I think about how to respond to the concurrent cataclysms threatening the nation and the globe, I at least want to be Job—not a person with divine patience, but one who cares so much for his fellow mortals that he will spit acidic truth into the face of the Lord to the very end.

What’s the alternative? Giving up? Waiting for oblivion? Such an attitude is its own kind of submissive patience. It’s understandable—but when things inevitably get even darker than they are today, it will be about as useful as waiting for God to save the day. What Job has given me is not exactly hope. But it’s something.

No comments:

Post a Comment