Somewhere along the way we let most children down badly in terms of reading. Reading must be done first for pleasure. The rest comes later. Some of this is done in the school but it really needs to be booked into the evening routine in which perhaps the child is encouraged to read a favorite book on his own for pleasure before bedtime.

The iphone has filled in a lot of the historic gap but encourages frenetic browsing and we have all forgotten how to read for pleasure and contemplative meditation as well. That truly needs to also be encouraged.

Technology has actually made us all real readers and writers. It is called practice. Is it possible that the decline in television viewership is because the population of stupid people has declined? What if it is true that the MSM is catering only to a deficient sector of their audience and has completely lost the majority of their potential audience? They are serving up political propaganda and soap opera. ..

The real take home is that tailored intelligent entertainment product is the real future of all Mass Media. Suppose we create historic dramas curated by historians? That has started sort off on PBS.

I review articles mostly about science to provide my readers a key background piece. Inter lacing that with an active discussion of the screen is a viable approach. Would it also be entertaining? How about interactive commentary as well?

We are doing better and will do a lot better as the Holodec finally kicks in.

How do you turn kids into bookworms? All 10 children's laureates share their tips

Michael Morpurgo, Quentin Blake, Julia Donaldson and more reveal the books that inspired them and how to keep children interested in a world of digital distractions

Sat 11 May 2019 08.00 BST Last modified on Sat 11 May 2019 09.38 BST

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2019/may/11/how-do-you-turn-kids-into-bookworms-all-10-childrens-laureates-share-their-tips?

It began in front of a log fire after a convivial dinner with friends and neighbours, Ted and Carol Hughes. I was grumbling about the lack of attention and credit generally given in the adult world to children’s books. Hughes, poet laureate at the time, said something like: “A fine children’s book is as important and worthwhile as any kind of literature, and maybe more so. Read and love a great story or poem when you’re young and the chances are that you’ll become a reader for life, and maybe a writer or an artist. Something should be done.”

“You’re the poet laureate,” I ventured, “maybe we should have a children’s laureate?”

It was a throwaway line. Then he said: “Why not? Let’s do it.” So the laureate story began, and took shape.

Quentin Blake was crowned our first children’s laureate on 10 May 1999. He set the standard, and in his two years brought the art of illustration of children’s books to the public eye in a way never done before. The first chapter was a stunning beginning and each of the nine since has taken the children’s laureate story in a different direction, always exciting, surprising, and enlightening. Each of the laureates has given fresh inspiration to so many thousands of readers, raising ever greater awareness of the importance of children’s literature in our culture and in our society. And like all the best stories, no one knows where the next chapter might lead us, and like the best books, we never want them to end. Michael Morpurgo

Quentin Blake

(Children’s laureate from 1999 – 2001)

I remember the book that almost stopped me reading was Oliver Twist, which I was given to read when I was too young. Fortunately I came back to Dickens later, when I thought it was absolutely amazing. I have since read all the books, some of them twice. A simpler story is a book that I illustrated, by my friend John Yeoman, called Featherbrains. It tells the story of two chickens who escape from a battery farm and are introduced to the wide world through the wisdom of a friendly jackdaw.

Anne Fine

Like almost everyone else my age, I was turned into a reader by Enid Blyton. I also adored Anthony Buckeridge’s books about Jennings and his prep school. But Richmal Crompton’s William was my favourite character. I had almost all of the 39 books, and he became my imaginary brother and the perfect companion: lippy, irrepressible, and inventive to an almost pathological degree.

Children have never been famed for taking sensible advice, but are superb at following a poor example. So if a parent spends most of their own time peering at screens, they can scarcely expect anything different from their offspring. Add to this the fact that all studies show that children who are read to every night do better in school – even in maths. Maybe you can’t dump your phone, but at least give them that one half-hour in the day totally uninterrupted. And start young.

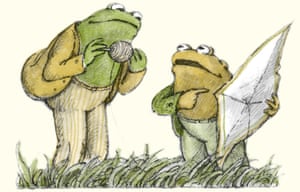

The Frog and Toad books by Arnold Lobel have turned so many into passionate readers. Young children adore these wry, intelligent and gentle stories. Frog is patient and modest. Toad is not. But together they face the problems all children recognise: ice creams that melt too fast, lost buttons, failure of will power, and all the myriad misunderstandings, anxieties and triumphs of small busy lives. No adult I know ever tires of reading these books aloud. (I’ve seen grown men reduced to tears of laughter by some of Frog and Toad’s confusions.) Bedtime reading fosters security, intimacy and understanding. The library makes it cheap, and it’s already easy. What’s not to like?

Michael Morpurgo

It’s not always possible for parents to make time for reading so it needs to start with school. I know it’s something I’ve talked about before but just half an hour at the end of the school day, every day, as story time, so that listening to stories becomes a habit, books become a habit and a moment of quiet to share a story that the teacher loves.

Reading is not a medicine. There isn’t one book that works for every child because every child is different. Treasure Island was the first real book that I read for myself – it was a huge inspiration. I identified with Jim Hawkins completely, and lived this book as I read it. Robert Louis Stevenson became a hero of mine, and Treasure Island was the beginning of a long voyage into stories.

Advertisement

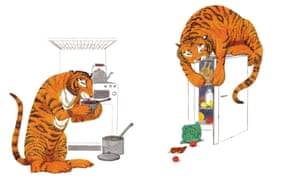

For very young children I’d choose Judith Kerr’s The Tiger Who Came to Tea and for older readers, The Man Who Planted Trees by Jean Giono. It’s a book for children from 8 to 80. I love the humanity of this story and how one man’s efforts can change the future for so many. It’s a real message of hope.

Jacqueline Wilson

(2005 – 2007)

When I was a little girl my mum was always telling me to get my head out of my book and do something useful. Teachers at school hoiked me out of cosy reading corners and told me to run about in the playground. Consequently reading became ever more desirable! It’s tempting therefore to suggest that we tell children nowadays to stop reading at once – but I’m not sure this would really work.

Reading aloud to small children is a way to get them to associate a book with fun and pleasure and attention. Most toddlers love to cuddle up on a lap and point at the pictures and join in with a well-loved text. When children can read for themselves, it’s still a delight to read an exciting long challenging book they wouldn’t want to tackle alone.

Where the Wild Things Are by Maurice Sendak is a starter book that will please every small child and have them joining in their own wild rumpus. Hopefully reading will continue to be a never-ending magical adventure.

Michael Rosen

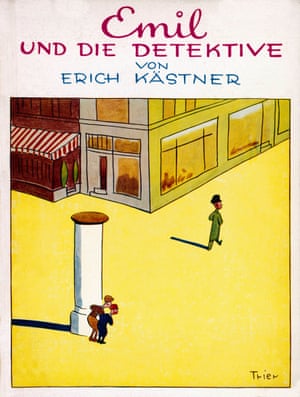

Facebook Twitter Pinterest Wit and tension … Emil and the Detectives by Erich Kästner. Photograph: Chronicle/Alamy

I fell in love with Emil and the Detectives by Erich Kästner. Emil’s mother sends him to Berlin with some money for his aunt and grandmother, but the money is stolen by a stranger on the train … for its inventiveness, wit and tension it became my favourite book as a child, and one that I went on to teach as an adult.

One key barrier is the overprescriptive and narrow testing regime in primary schools. It inhibits teachers from reading with children in a relaxed open-ended way. The test questions are too narrow, too yes-no. The way forward is for schools to try to spend as much time implementing a wide ranging, fully inclusive reading for pleasure programme. It must involve the whole school community including parents, grandparents and carers – a cultural in-school and out-of-school policy.

Browsing and choosing are vital and necessary starters – it teaches us about how reading can be part of our lives and how it can matter. As a starter, I would recommend The Gruffalo by Julia Donaldson. It’s about the triumph of wit and cunning over adversity and danger. It’s funny and it’s got real tension and it gets better and better on each rereading, and there is so much to look at with Axel Scheffler’s pictures, as well as the perfect rhythm and rhyme that Julia has written.

Anthony Browne

(2009 – 2011)

When I was a child, comic books were a big influence and I remember one in particular – a comic strip in book form – called Fudge in Toffee Town. It was child‑friendly surrealism: Toffee Town was made out of sweets and the rivers were lemonade. I thought it was wonderful, particularly coming out of wartime rationing.

Talking and listening and laughing with children are some of the most important ways to spend time together, and a book can be as engaging as a toy or a screen if they are part of a shared experience. Most picture books can produce fascinating conversations between adult and child if approached in an interesting and interested way. Look together at the pictures and talk about the expressions on characters’ faces, their body language or position on the page in relation to others. It can be a bit like “people watching” in real life – what sort of a place do they live in? Are they happy or sad? Are there any clues in the picture? These are merely my suggestions as a writer, illustrator and parent but, of course, there are no rules.

Julia Donaldson

(2011 – 2013)

I was given The Book of a Thousand Poems when I was five years old. It was a big, fat book and I loved reading, learning and reciting the poems together with my father. It also inspired me to begin making up some of my own.

Once children have learned to read, bedtime stories can sometimes become a thing of the past. I think this is a shame. With library closures and so little review space given to children’s books it can be hard for them to find books they might enjoy and to acquire the habit of reading for themselves. Reading aloud to children of any age can be hugely enjoyable for all concerned, so I think a serial story at bedtime is a good idea. (And if you leave it on a cliffhanger, maybe there will be a torch under the bedclothes.)

We used to record ourselves reading our children’s favourites, so they could listen to them in the car. If this seems a tall order, there are lots of great audio editions out there. My recommendation is Millions by Frank Cottrell-Boyce. It’s about two brothers who discover a bag full of money that they have to spend in just a couple of days.

Facebook Twitter Pinterest The Gruffalo by Julia Donaldson, illustrated by Axel Scheffler. Photograph: Julia Donaldson

Malorie Blackman

(2013 – 2015)

From a very early age, I instinctively felt the value of stories. The Silver Chair by CS Lewis is about the power of believing in yourself no matter what, even when others are ridiculing you. This was a message I desperately needed to hear at the time – and it’s one that has stayed with me to this day.

If we want children to learn, to grow by understanding and having empathy for others, to thrive, then we must encourage them to read for pleasure. Let your children see you reading. Read to them. Let them read to you. Don’t criticise what they are reading or how long it may take them. As a child, if I read a wonderful paragraph or page in a book, I’d read it over and over again, savouring the words, the meaning. Part of the beauty of reading for pleasure is the way that the story moves at the pace of the reader. Don’t laugh at or ridicule children’s reading choices. Encourage them to read more of what they like as well as suggesting other books just waiting to be read and loved.

My recommendation to inspire older children to pick up a book would be V for Vendetta by Alan Moore, illustrated by David Lloyd. Reading for pleasure opens so many doors in a world that seems to increasingly seek to close them. Books and love are made for sharing.

Chris Riddell

Advertisement

(2015 – 2017)

The greatest barrier to children’s literacy is the lack of a librarian in a school. They are there to guide, to advise, to recommend – they are the gatekeepers to new worlds and initiate an introduction to new friends on the page. During my time as laureate I was determined to highlight their work and was lucky enough to witness first-hand the positive effect a librarian has on the pupils in the classroom. Their knowledge is absolutely fundamental to reading for pleasure.

With funding cuts and budget pressures, there is a risk of librarians becoming an endangered species and that would be a tragedy for our children. It is essential that the government recognise the skills that librarians give to the community they serve, not just in schools but in public libraries as well – giving everyone, from every background, access to books. My school librarian recommended JD Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye to me when I was a teenager – without it I’m not sure I’d be where I am today.

Lauren Child

Facebook Twitter Pinterest ‘The character that stayed with me’ … Pippi Longstocking. Photograph: Lauren Child

The pressure on schools to achieve certain things means there isn’t much time for reading or even just to unwind. There isn’t time in the day to just sit and talk about books and stories. Children need to get into the habit of hearing stories and of having books around them. They need to be confident in spaces where books are a familiar thing and to have opportunities to engage with books and look at illustrations. That could be through libraries or having books in the classroom, or authors and illustrators coming into schools regularly.

Advertisement

When we were young, my parents always took us to galleries and I know that made us comfortable with the language of looking at pictures. People often talk about the one book they discovered as a child that made them a reader. For me, the biggest influence was Pippi Longstocking. She was a character that I loved and has stayed with me ever since.

Illustration: Owen Gatley/The Guardian

No comments:

Post a Comment