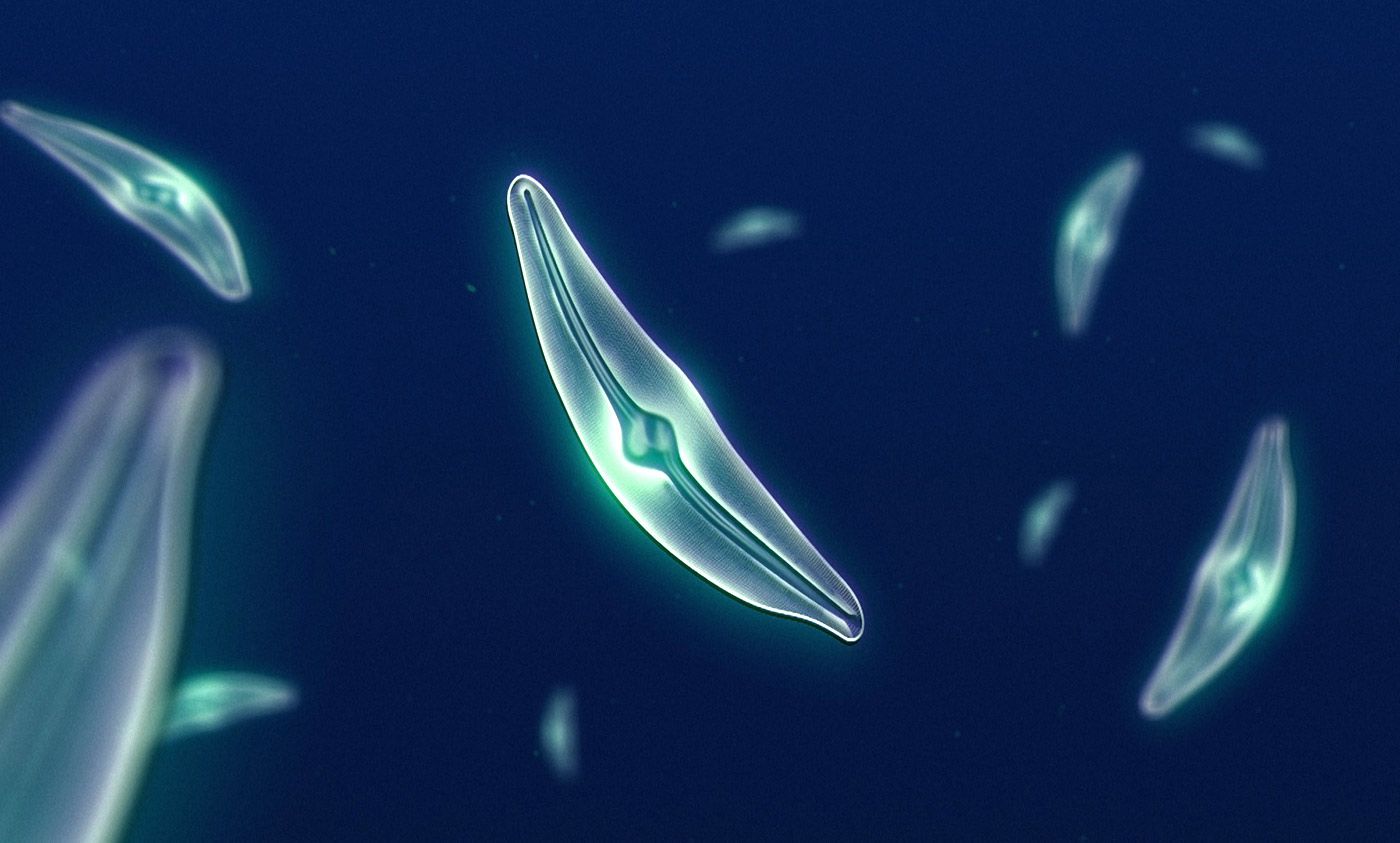

Diatoms. Photo courtesy NASA

https://aeon.co/ideas/there-are-more-microbial-species-on-earth-than-stars-in-the-sky?

https://aeon.co/ideas/there-are-more-microbial-species-on-earth-than-stars-in-the-sky?

For centuries, humans have endeavoured to discover and describe the

sum of Earth’s biological diversity. Scientists and naturalists have

catalogued species from all continents and oceans, from the depths of

Earth’s crust to the highest mountains, and from the most remote jungles

to our most populated cities. This grand effort sheds light on the

forms and behaviours that evolution has made possible, while serving as

the foundation for understanding the common descent of life. Until

recently, our planet was thought to be inhabited by nearly 10 million

species (107). Though no small number, this estimate is based almost solely on species that can be seen with the naked eye.

What about smaller species such as bacteria, archaea, protists and fungi? Collectively, these microbial taxa are the most abundant, widespread and longest-evolving forms of life on the planet.

What is their contribution to global biodiversity? When microorganisms are taken into account, recent studies suggest that Earth might be home to a staggering 1 trillion (1012) species. If true, then the grand effort to discover Earth’s biodiversity has only come within a 1,000th of 1 per cent of all species on the planet.

Estimating microbial diversity even in the most ordinary of habitats presents a unique set of challenges. For more than a century, scientists identified microbial species by first culturing them on Petri dishes and then characterising cellular properties, along with aspects of their physiology such as thermal tolerances, the substrates they consume, or the enzymes they produce. Such approaches dramatically underestimate diversity, not only because it is difficult to grow the vast majority of microorganisms, but also because unrelated microbial species can perform similar functions and are unlikely to be distinguished by their appearance.

During the mid-1990s, a growing number of microbiologists began to abandon cultivation techniques in favour of identifying organisms by directly sequencing nucleic acids – DNA – from ocean water, leaf surfaces, wetland sediments, and even the biofilms inside of showerheads. Over the past decade, these methods have been dramatically refined so that millions of individual microbes can be sampled at once. With this high-throughput approach, we have learned that a single gramme of agricultural soil can routinely contain more than 10,000 species. Similarly, we know that nearly 10 trillion (1013) bacterial cells make up a human’s microbiome. These microbes not only aid in their host’s digestion and nutrition, but also represent an extension of its immune system. Looking beyond ourselves, microbes are found in Earth’s crust, its atmosphere, and the full depth of its oceans and ice caps. In total, the estimated number of microbial cells on Earth hovers around a nonillion (1030), a number that outstrips imagination and exceeds the estimated number of stars in the Universe. Naturally, this begs the question of how many species might actually exist.

What about smaller species such as bacteria, archaea, protists and fungi? Collectively, these microbial taxa are the most abundant, widespread and longest-evolving forms of life on the planet.

What is their contribution to global biodiversity? When microorganisms are taken into account, recent studies suggest that Earth might be home to a staggering 1 trillion (1012) species. If true, then the grand effort to discover Earth’s biodiversity has only come within a 1,000th of 1 per cent of all species on the planet.

Estimating microbial diversity even in the most ordinary of habitats presents a unique set of challenges. For more than a century, scientists identified microbial species by first culturing them on Petri dishes and then characterising cellular properties, along with aspects of their physiology such as thermal tolerances, the substrates they consume, or the enzymes they produce. Such approaches dramatically underestimate diversity, not only because it is difficult to grow the vast majority of microorganisms, but also because unrelated microbial species can perform similar functions and are unlikely to be distinguished by their appearance.

During the mid-1990s, a growing number of microbiologists began to abandon cultivation techniques in favour of identifying organisms by directly sequencing nucleic acids – DNA – from ocean water, leaf surfaces, wetland sediments, and even the biofilms inside of showerheads. Over the past decade, these methods have been dramatically refined so that millions of individual microbes can be sampled at once. With this high-throughput approach, we have learned that a single gramme of agricultural soil can routinely contain more than 10,000 species. Similarly, we know that nearly 10 trillion (1013) bacterial cells make up a human’s microbiome. These microbes not only aid in their host’s digestion and nutrition, but also represent an extension of its immune system. Looking beyond ourselves, microbes are found in Earth’s crust, its atmosphere, and the full depth of its oceans and ice caps. In total, the estimated number of microbial cells on Earth hovers around a nonillion (1030), a number that outstrips imagination and exceeds the estimated number of stars in the Universe. Naturally, this begs the question of how many species might actually exist.

Long lists of species have been made for nearly every ecosystem on Earth, with nearly 20,000 plant and animal species discovered

each year. Many of these species happen to be beetles, but reports of

rodents, fish, reptiles and even primates are not uncommon. While

exciting to biologists and the public alike, new plant and animal

species contribute only around 2 per cent per year to the total number

of species, a sign that we might be approaching a near-complete census

of those organisms on the planet.

In sharp contrast, deep lineages

containing untold species are being described at a rapid rate in the

microbial world. A few years ago, from a single aquifer in Colorado,

scientists found

35 new bacterial phyla; a phylum is a broad group containing thousands,

tens of thousands or, for microbes, even millions of related species.

The phyla discovered in that one aquifer amounted to 15 per cent of all

previously recognised bacterial phyla on Earth. To put this in context,

humans belong to the phylum Chordata, but so do more than 65,000 other

species of animals that possess a notochord (or skeletal rod), including

mammals, fish, amphibians, reptiles, birds and tunicates. Such findings

suggest that we are at the tip of the iceberg in terms of describing

diversity of the microbial biosphere.

Ideally, there should be

agreement on what constitutes a species if we are to achieve an estimate

of global biodiversity. For plants and animals, a species is generally

defined as a group of organisms that are able to mate and produce viable

offspring. This definition, unfortunately, is not very useful for

classifying microbial species because they reproduce asexually.

(Microorganisms can transfer genes among closely related

individuals through processes known as ‘horizontal gene transfer’, which

is akin to the recombination that occurs in sexually reproducing

organisms.)

Nevertheless, there are ways of categorising organisms

based on shared ancestry, which can be inferred from genetic data. The

most commonly used technique for delineating microbial taxa involves

comparisons of ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene sequences. This gene is

involved in building ribosomes, the molecular machines that are required

for protein synthesis among all forms of life. By comparing the

similarities among sequences, scientists can identify groups of taxa

without needing to grow them or painstakingly characterise their

physiology or cellular structure. Of the many caveats associated with

this rRNA-based classification of microbial taxa is the fact that it

likely underestimates the true number of species. If so, then the recent

prediction that Earth might be home to as many as 1012 species could, in fact, be a conservative estimate, despite its incredible magnitude.

Knowing

the number of microbial species on Earth could have practical

implications that improve our quality of life. The prospect of yet-to-be

harnessed biodiversity might spur development of alternative fuels to

meet growing energy demands, new crops to feed our rapidly growing

population, and medicines to fight emerging infectious diseases. But

perhaps there is a more basic reason for wanting to know how many

species we share the planet with. Since the predawn of civilisation, the

survival of our species depended on trials and errors with plants,

animals and microbes that we attempted to harvest, domesticate or avoid

all together. Our interest in biodiversity also reflects an intrinsic

curiosity about the natural world and our place within it. Whether to

admire, protect, transform or exploit, humans have never sought to be

wholly ignorant of the species that inhabit Earth.

I have longed believed primordial microbes are the ORIGIN of all dis-ease. I am in the process of scientifically proving that theory. It is fascinating.

ReplyDeleteDr, James Chappell