None of this can truly change until we master the resolution of poverty itself. That must include the natural availability of the four hour shift directly tied to Community needs. Education itself needs to stop been a mere warehouse and a directed experience aimed at optimizing results.

Yet way more important, we need to correctly support the agricultural enterprise with robots. Grass must be cut back and machetes can be operated by robots as easily as kids. Our problem is that it is either or. That is going to change out over the next generation.

Yet for all the complaining in this article, this has been the superior alternative to the past. Recall surplus children were sold directly into the slave trade as happens today in SE Asia and elsewhere.

Children need to expect to work or contribute safely and also master their schoolwork as all those American farm boys and girls of our past.. .

.

From bean to bar

In Ivory Coast, Switzerland, Belgium and the Netherlands, chocolate makers are on a mission to keep children out of cocoa production

By John Aglionby and Ralph Atkins

https://ig.ft.com/special-reports/child-labour/

The farmers

Cocoa pods: key ingredient of a bar of chocolate

Bledgi Yode has lost count of how often he was injured as a child working on his family’s cocoa farm. The two-hectare holding is in the village of Ziguédia, 15km up a dirt track, south-west of the city of Daloa in central Ivory Coast.

“We started working in the fields aged six or seven and were digging and using machetes from when we were eight,” says the subsistence farmer, now 58. He mimes slashing grass with a long blade as he walks among cocoa trees laden with ripening pods. “We often hurt ourselves but we had no choice. My father said we wouldn’t eat if we didn’t work in the plantation.”

Three decades later, in the late 1990s, Mr Yode, treated his eldest son, Ange, exactly the same. “Like me, he went to school but he also had to work in the fields,” Mr Yode says. “It was the way things were done.”

Cocoa pods: key ingredient of a bar of chocolate

Bledgi Yode has lost count of how often he was injured as a child working on his family’s cocoa farm. The two-hectare holding is in the village of Ziguédia, 15km up a dirt track, south-west of the city of Daloa in central Ivory Coast.

“We started working in the fields aged six or seven and were digging and using machetes from when we were eight,” says the subsistence farmer, now 58. He mimes slashing grass with a long blade as he walks among cocoa trees laden with ripening pods. “We often hurt ourselves but we had no choice. My father said we wouldn’t eat if we didn’t work in the plantation.”

Three decades later, in the late 1990s, Mr Yode, treated his eldest son, Ange, exactly the same. “Like me, he went to school but he also had to work in the fields,” Mr Yode says. “It was the way things were done.”

Family business: farmer Bledgi Yode

For much of Mr Yode’s life, child

labour was standard practice in Ivory Coast and neighbouring Ghana, the

world’s two largest cocoa producers, which together account for some 60

per cent of global supply. But working practices are starting to change

for Mr Yode’s family of 11 children. His youngest son, 10-year-old

Jean-Luc, has escaped the most arduous physical labour. “He comes and

watches us men work and does things like fetch drinking water, but he

does not do hazardous work,” Mr Yode says.

Change arrived in Ziguédia seven years ago, Mr Yode says, when the Ivory Coast government started to crack down on the use of child labour. Its campaign initially prosecuted employers of child labour and child traffickers, but then, after limited success, switched to encouragement as much as penalty. In 2015, for example, laws were passed that made schooling until the age of 16 both compulsory and free.

Change arrived in Ziguédia seven years ago, Mr Yode says, when the Ivory Coast government started to crack down on the use of child labour. Its campaign initially prosecuted employers of child labour and child traffickers, but then, after limited success, switched to encouragement as much as penalty. In 2015, for example, laws were passed that made schooling until the age of 16 both compulsory and free.

The changes happened partly because

of consumer pressure from the cocoa beans’ end users: the people who

buy chocolate bars. In order to please their customers, international

chocolate companies such as Nestlé, Barry Callebaut and Mars partnered

with local cocoa farmers’ co-operatives and certification agencies such

as Fairtrade and Rainforest Alliance to try to eliminate child labour

from their supply chains.

These alliances sought to educate adults about children’s rights, and build and improve schools and health facilities. Some schemes included women’s empowerment programmes and providing children with birth certificates. The latter are still a rarity across much of west Africa, and children without them are denied many legal rights.

These alliances sought to educate adults about children’s rights, and build and improve schools and health facilities. Some schemes included women’s empowerment programmes and providing children with birth certificates. The latter are still a rarity across much of west Africa, and children without them are denied many legal rights.

Education matters: outside a primary school in Bognonzra, east of Daloa

“We have to address the issue in a global manner, holistically, not just through one aspect,” says Amany Konan, a senior official in Ivory Coast’s Office of the First Lady, which is leading the fight against child exploitation. “It’s about education but also [addressing] poverty and lack of social infrastructure.”

Pierre Laporte, Ivory Coast country director at the World Bank, applauds the Ivorian government for its reform agenda but says farming practices are unlikely to change significantly in the foreseeable future. One challenge is that fluctuating prices put pressure on farmers. The government-guaranteed farm-gate price in 2017-18 is 700 CFA francs ($1.27) per kilogramme, 400 francs down on the previous year, following one of the most dramatic slumps in global prices in recent years.

Mr Konan says the government’s goal is to eliminate the worst forms of child labour by 2025. He admits, however, that this will happen only if current programmes are “rapidly accelerated and broadened”. He adds: “It will be a multigenerational challenge. We will have to keep doing follow-up work for years.”

The International Labour Organization defines child labour as work that deprives children of their childhood, potential and dignity, interferes with schooling and is harmful to their physical and mental development. Activities such as lifting heavy loads or working with dangerous tools or chemicals are considered among the worst forms.

In west Africa, child labour has been perpetuated by the way cocoa is grown — on small plots of a few hectares each. The majority of the 900,000 cocoa farmers in Ivory Coast, who between them have almost 4m children, struggle to earn enough to stay above the poverty line. Sometimes child labour is the farmers’ only option.

Three years ago, Ecojad, a Daloa-based cocoa farmers’ co-operative with financial backing from Tony’s Chocolonely, a Dutch chocolate-maker, began paying farmers in Ziguédia a premium for their beans if they did not use child labour. Tony’s Chocolonely promises consumers “slavery-free chocolate”.

Some of the money was in cash and some arrived through community projects. These have included new toilets at a local school, a pump in the village so people no longer have to walk miles for water, and two programmes to provide women with greater income.

On a tour of supplier farms and co-operatives in Ivory Coast, Henk Jan Beltman, chief executive of Tony’s Chocolonely, is clearly delighted about the progress so far. But he stresses in a meeting with two dozen villagers in Blaisekro, about 50km east of Daloa, that everyone has to play their part. “My responsibility is to build the brand and yours is to develop the village,” he says. “The co-operative’s role is to make sure the children go to school. If we work together we will have [a] long-term impact.”

Listening and learning, left to right: Henk Jan Beltman, Korotoum Doumbia, a cocoa sector consultant, and Alphonse Zaha Silue, of Kapatchiva cocoa co-operative, tour a primary school in Blaisekro village

Mr Beltman admits he cannot guarantee that every chocolate bar his company sells is 100 per cent child-labour free. The numbers of farmers involved, often in remote locations, makes ensuring full compliance impossible, and on-the-ground definitions of what constitutes child labour can be a matter of individual judgment.

“If a child is used to carrying a machete, who are we to block it?” asks Mr Beltman. “As long as a child’s education and development are not hindered, I’m not against children doing some work.”

“The projects really do make a difference,” says Bakayoko Gondo, the headteacher of the primary school in Ziguédia. “Now we have latrines, the children are happy and they’re healthier.”

Bakayoko Gondo, headteacher of the primary school in Ziguédia

School attendance has risen 15 per cent

since the smart stone building with a corrugated iron roof was

completed last year, he adds.

Programmes such as those in Ziguédia, however, make only a small

difference overall. Tony’s Chocolonely will buy about 7,600 tons of

beans from Ivory Coast in 2018, which is less than 0.5 per cent of the

country’s total production of 1.8m tons.

Nestlé, one of the world’s biggest chocolate companies, highlighted

the scale of the challenge in a report it published in 2017, five years

after the company started to focus on the problem. The report

said that of 40,728 children aged five to 17 who were monitored at

48,496 producers, 7,002 were undertaking work they should not have been

doing.

Nevertheless, despite the work of

the company, NGOs and co-operatives, 49 per cent of the children

interviewed last year by the International Cocoa Initiative in a

separate survey of a representative sample of 1,056 were found to be

engaged in child labour. The ICI is an umbrella body that works with

governments, companies, co-operatives and NGOs to promote child

protection in the industry.

Christiane Kabron, who runs the ICI’s Daloa office, agrees that its work has just begun. “It will require a great effort by everyone for a long time to get to the end,” she says.

Christiane Kabron, who runs the ICI’s Daloa office, agrees that its work has just begun. “It will require a great effort by everyone for a long time to get to the end,” she says.

Bledgi Yode: children belong in schools, not in the fields

Mr Yode, who receives the Tony’s

Chocolonely premium for his harvest, accepts he will suffer as a result

of falling prices, not least because scarce government resources will be

stretched even more thinly. But he will continue to refuse to put any

children of his who are still aged under 18, to work. “We have to keep

moving forward and that means keeping our children in school,” he says.

Chocolate companies have long

associated themselves with charitable initiatives. In the US, Hershey

has a history of supporting educational and community initiatives. The

UK confectioner Rowntree, now part of Switzerland’s Nestlé, was founded

by a Quaker philanthropist who championed social reform, as were fellow

British chocolatiers Cadbury (now owned by Mondelez International) and

JS Fry.

Barry Callebaut is following a similar path. Just over half its

shares are owned on behalf of the Jacobs Foundation, which promotes

child and youth development and was set up in 1989 by Klaus Jacobs, a

member of the German-Swiss coffee family. “Over 50 per cent of our

dividend goes into education so, at the heart of the company, there is a

sense of responsibility,” says Mr De Saint-Affrique.

Pressure on chocolate companies to eradicate child labour has been

growing since at least the start of the century. In 2001, the industry

agreed the so-called Harkin-Engel Protocol, named after two US

politicians, with the aim of eradicating the worst forms of child labour

in the production of cocoa. The International Cocoa Initiative was

formed under the protocol’s auspices in 2002.

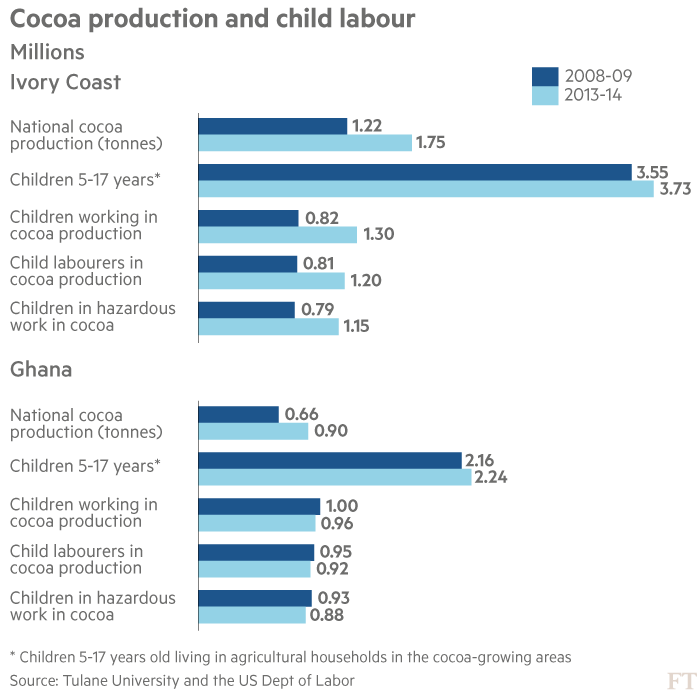

So far, however, such top-down approaches have not proved very

effective. “Industry, governments, social partners, the UN — we all have

unfortunately not got the traction that we need to really eliminate

child labour,” says Benjamin Smith, a technical specialist on child

labour at the International Labour Organization in Geneva. “The numbers

are not going in the right direction.”

Part of the problem, Mr Smith says, was the initial focus by the

industry on certification — labelling beans that were produced without

child labour. “That was always a ‘mission impossible’,” he says. The

certification process was hard to monitor and subject to manipulation.

“A lot of energy and resources went into certification, which could have

been more profitably invested in the root causes.”

Out of school:

boys sit alongside men at work on cocoa pods in Ivory Coast

Today, however, Mr Smith detects renewed determination by companies to tackle underlying problems. “The industry is experimenting and learning. Resources are being increased. There has been a major push in the past few years,” he says. “Consumers do have a role. It is important to get out the idea that the incomes that farmers receive, in many cases, are not adequate to really eliminate child labour.”

Like Tony’s Chocolonely, Barry Callebaut uses the Child Labour Monitoring and Remediation System (CLMRS), which was developed by the ICI for people to collect and track data on labour abuses via a mobile app. A progress report published last December showed that just 3.2 per cent of the 340 farmer groups in the Ivory Coast from which Barry Callebaut sources its beans had adopted the CLMRS. Some 247 cases of the worst forms of child labour were identified in 2016-17.

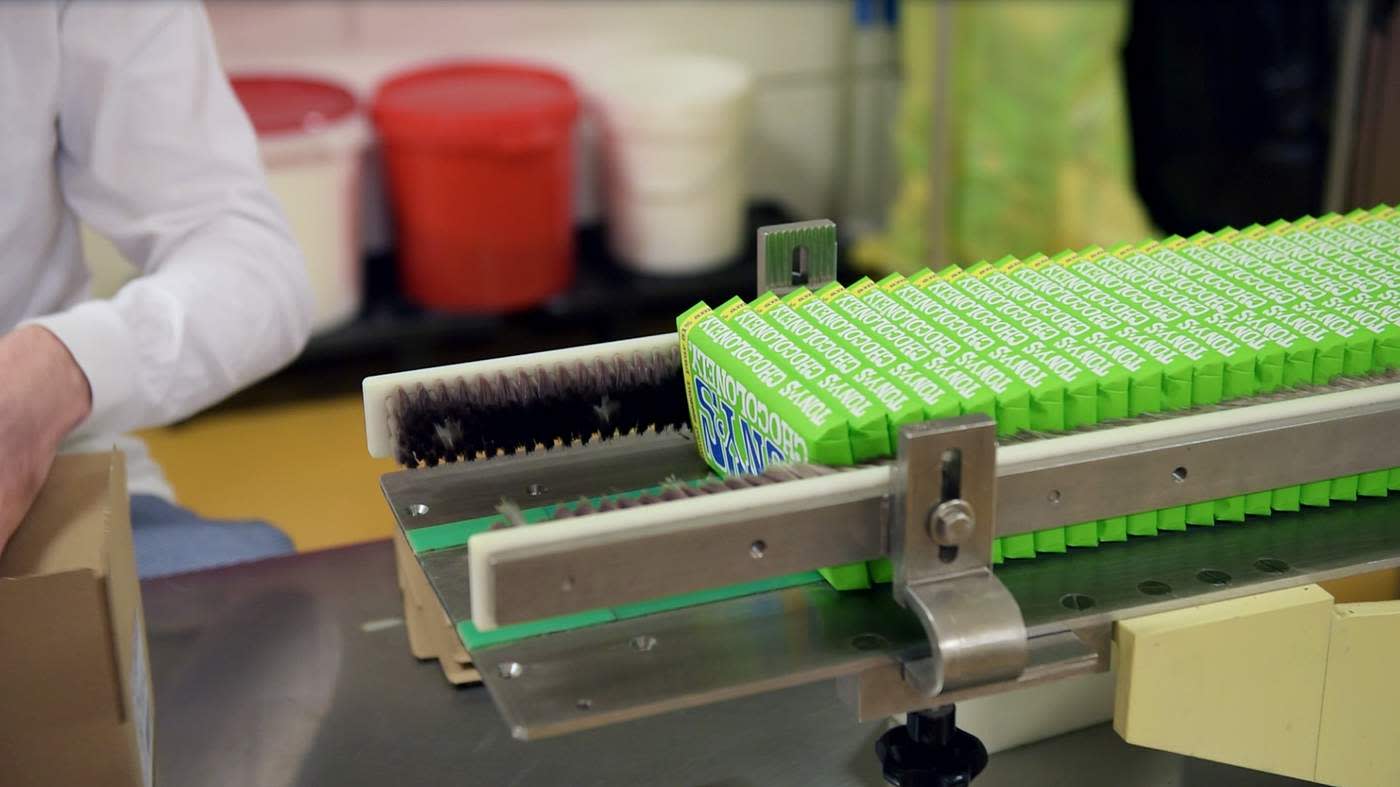

Bold by design: a strong identity was essential to help the brand stand out

In 2005, the two men decided to produce

chocolate bars themselves, using only ingredients they could ensure, as

far as possible, were produced without child labour. “Journalism as

marketing was basically my business model,” recalls Mr Dekkers. “I

started a company, not to sell as much chocolate as possible — of

course, that is necessary — but to change something in the minds of

people.”

The founders hoped that sales of their chocolate bars would help stamp out child labour in the wider industry — an ambitious task. Cocoa beans are just one of many ingredients that Tony’s needs to ensure is ethically sourced — from sugar to flavourings such as cinnamon and cardamom. They also needed to consider the materials in the chocolate bars’ packaging.

The founders hoped that sales of their chocolate bars would help stamp out child labour in the wider industry — an ambitious task. Cocoa beans are just one of many ingredients that Tony’s needs to ensure is ethically sourced — from sugar to flavourings such as cinnamon and cardamom. They also needed to consider the materials in the chocolate bars’ packaging.

Based in a renovated red-brick

19th-century gasworks not far from the centre of Amsterdam, Tony’s head

office has the air of a technology start-up, with its young, casually

dressed staff, flexible work practices and a whimsical tone to its brand

identity and communications.

Staff are known as “Tonys” and sign off emails with the salutation “Best choco greetings”. Every six months a ballot decides where they sit in the office. Colleagues in the same department are forbidden to sit together, to encourage integration and idea-sharing.

Staff are known as “Tonys” and sign off emails with the salutation “Best choco greetings”. Every six months a ballot decides where they sit in the office. Colleagues in the same department are forbidden to sit together, to encourage integration and idea-sharing.

Melting pot: employees from different departments are mixed together

“It’s a little bit of the Willy Wonka

feel,” says Mr Beltman, dubbed in Tony’s Chocolonely-speak as “chief

chocolate officer”. He adds: “We’re in your face, full on, full flavour…

10 per cent of people buy [our chocolate] because we have a purpose; 90

per cent buy us for the fact that we’re a fun company, with tasty

chocolate and a cool brand.”

Mr Beltman, who previously worked

for Heineken, the Dutch beer company, and Innocent, the UK

smoothie-maker, became the majority shareholder in Tony’s in 2011,

paying €382,500 for his stake. Tony’s now claims a market share of

almost 17 per cent in the Netherlands. Mr Beltman insists the business

model is scalable. “I’m naive and arrogant, but if we can do it and

become the number one chocolate [bar] company in the Netherlands, why

can’t others do it too?” he says.

Mr Beltman reckons Tony’s is still in its “entrepreneurial phase”. It is aiming for 50 per cent revenue growth, to reach about €67m in the financial year ending this September. With Tony’s products already available in the US, it plans to carry out feasibility studies in the UK before launching its products there, probably starting in specialist food shops. Tony’s sells online, in supermarkets and at airports, but “we’re crap at opening stores”, says Mr Beltman. The company has opened a store next to its headquarters to help gauge consumer tastes directly.

Mr Beltman reckons Tony’s is still in its “entrepreneurial phase”. It is aiming for 50 per cent revenue growth, to reach about €67m in the financial year ending this September. With Tony’s products already available in the US, it plans to carry out feasibility studies in the UK before launching its products there, probably starting in specialist food shops. Tony’s sells online, in supermarkets and at airports, but “we’re crap at opening stores”, says Mr Beltman. The company has opened a store next to its headquarters to help gauge consumer tastes directly.

Ultimately, his ambition is to sell the

business to a big chocolate-maker. “If we can sell it to a chocolate

multinational [and] have an impact from the inside out, that’s my

dream.” This is because Tony’s remains half-company, half-campaign. It

wants to prove that child labour-free production is a viable business

strategy. It was certified as a B Corp — a designation that demands

greater accountability for broad social and environmental standards — in

2013. “What we want to do is to have [an] impact in mainstream

chocolate,” Mr Beltman says. This means that “everything we do has to be

scalable”.

With this in mind, Tony’s has

chosen to work with the world’s biggest chocolate-makers, and is part of

the ICI. Board members include Hershey, Mars, Mondelez, Nestlé, Barry

Callebaut and Cargill, the agricultural commodities trader.

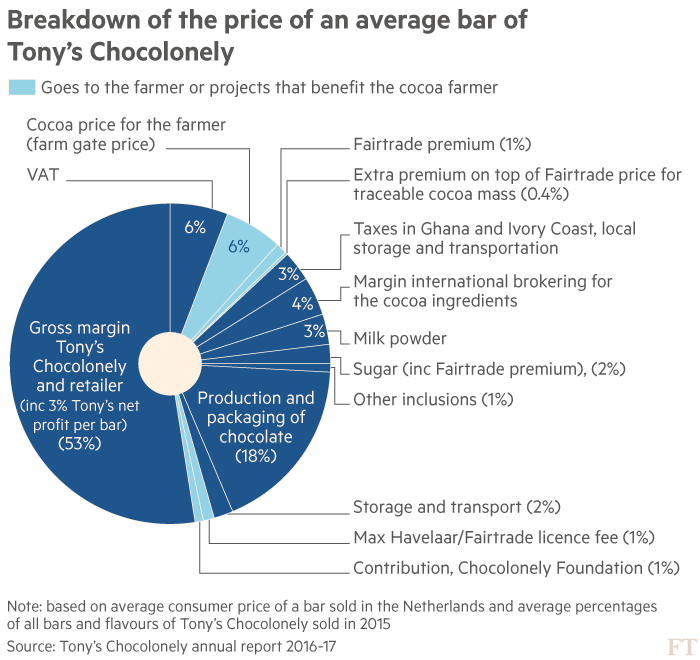

The strategy is straightforward: Tony’s pays above the market price for its beans, adding $200 per tonne to qualify for the Fairtrade label, plus a “Tony premium” of at least $175 a tonne. It also agrees long-term contracts of at least five years, so the farmer can invest in production facilities, and offers help in boosting quality and productivity. These extra costs, Tony’s reckons, make its chocolate 15-20 per cent more expensive than competitors’. A 180g Tony’s bar usually sells for between €2.75 (in supermarkets) and €3.05.

The strategy is straightforward: Tony’s pays above the market price for its beans, adding $200 per tonne to qualify for the Fairtrade label, plus a “Tony premium” of at least $175 a tonne. It also agrees long-term contracts of at least five years, so the farmer can invest in production facilities, and offers help in boosting quality and productivity. These extra costs, Tony’s reckons, make its chocolate 15-20 per cent more expensive than competitors’. A 180g Tony’s bar usually sells for between €2.75 (in supermarkets) and €3.05.

On their way: the bars will go on sale through supermarkets, specialist shops and online

Bigger rivals admire Tony’s enthusiasm

but say the steps the company has taken are already commonplace. “I love

their passion, their single reason for being,” says an executive at one

of the biggest global chocolate companies. “But all these things are

becoming standard. You have to do it — it is not a competitive

advantage.”

At Barry Callebaut, Mr De Saint-Affrique points out that there is a potential shortcut to guaranteeing child labour-free chocolate. His company could simply source all its cocoa beans from regions outside Africa where child labour is less of an issue. But that would mean abandoning farmers like Mr Yode in Ziguédia, who are now becoming financially stable enough to keep the next generation out of child labour thanks to the co-operative schemes.

“You could suddenly say that you are sustainable, and you wouldn’t have changed anything,” Mr De Saint-Affrique reflects. “Actually, you’d have changed the world of small farmers in Africa for the worse.”

At Barry Callebaut, Mr De Saint-Affrique points out that there is a potential shortcut to guaranteeing child labour-free chocolate. His company could simply source all its cocoa beans from regions outside Africa where child labour is less of an issue. But that would mean abandoning farmers like Mr Yode in Ziguédia, who are now becoming financially stable enough to keep the next generation out of child labour thanks to the co-operative schemes.

“You could suddenly say that you are sustainable, and you wouldn’t have changed anything,” Mr De Saint-Affrique reflects. “Actually, you’d have changed the world of small farmers in Africa for the worse.”

No comments:

Post a Comment