Anger is temporary madness: the Stoics knew how to curb it

Massimo Pigliucci is professor of philosophy at City College and at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York. His latest book is How to Be a Stoic: Ancient Wisdom for Modern Living (2017). He lives in New York.

Was Seneca right to believe that anger is a temporary madness?

https://aeon.co/ideas/anger-is-temporary-madness-heres-how-to-avoid-the-triggers

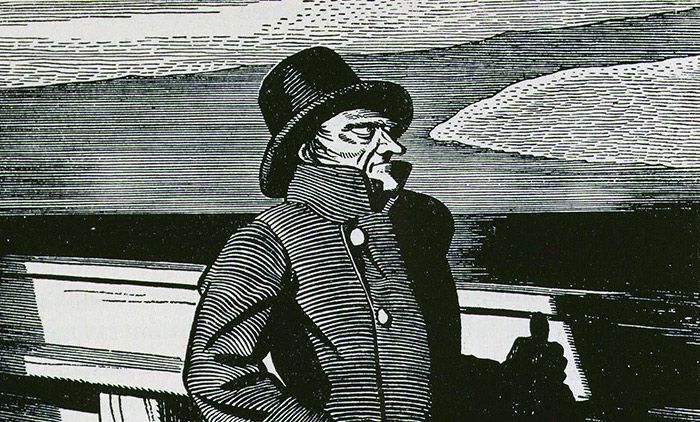

Rockwell Kent's illustration of Captain Ahab from the 1937 edition of Moby Dick.

People get angry for all sorts of reasons, from the trivial ones (someone cut me off on the highway) to the really serious ones (people keep dying in Syria and nobody is doing anything about it). But, mostly, anger arises for trivial reasons. That’s why the American Psychological Association has a section of its website devoted to anger management. Interestingly, it reads very much like one of the oldest treatises on the subject, On Anger, written by the Stoic philosopher Lucius Annaeus Seneca back in the first century CE.

Seneca thought that anger is a temporary madness, and that even when justified, we should never act on the basis of it because, though ‘other vices affect our judgment, anger affects our sanity: others come in mild attacks and grow unnoticed, but men’s minds plunge abruptly into anger. … Its intensity is in no way regulated by its origin: for it rises to the greatest heights from the most trivial beginnings.’

The perfect modern milieu for anger management is the internet. If you have a Twitter or Facebook account, or write, read or comment on a blog, you know what I mean. Heck, Twitter anger has been brought up to new heights (or lows, depending on your point of view) by the current president of the United States, Donald Trump.

I too write quite a bit on online forums. It’s part of my job as an educator, as well as, I think, my duty as a member of the human polis. The conversations I have with people from all over the world tend to be cordial and mutually instructive, but occasionally it gets nasty. A prominent author who recently disagreed with me on a technical matter quickly labelled me as belonging to a ‘department of bullshit’. Ouch! How is it possible not to get offended by this sort of thing, especially when it’s coming not from an anonymous troll, but from a famous guy with more than 200,000 followers? By implementing the advice of another Stoic philosopher, the second-century slave-turned-teacher Epictetus, who admonished his students in this way: ‘Remember that it is we who torment, we who make difficulties for ourselves – that is, our opinions do. What, for instance, does it mean to be insulted? Stand by a rock and insult it, and what have you accomplished? If someone responds to insult like a rock, what has the abuser gained with his invective?’

Indeed. Of course, to develop the attitude of a rock toward insults takes time and practice, but I’m getting better at it. So what did I do in response to the above-mentioned rant? I behaved like a rock. I simply ignored it, focusing my energy instead on answering genuine questions from others, doing my best to engage them in constructive conversations. As a result, said prominent author, I’m told, is livid with rage, while I retained my serenity.

Now, some people say that anger is the right response to certain circumstances, in reaction to injustice, for instance, and that – in moderation – it can be a motivating force for action. But Seneca would respond that to talk of moderate anger is to talk of flying pigs: there simply isn’t such a thing in the Universe. As for motivation, the Stoic take is that we are moved to action by positive emotions, such as a sense of indignation at having witnessed an injustice, or a desire to make the world a better place for everyone. Anger just isn’t necessary, and in fact it usually gets in the way.

The philosopher Martha Nussbaum gave a famous modern example of this in her Aeon essay on Nelson Mandela. As she tells the story, when Mandela was sent to prison – for 27 years – by the Apartheid government of South Africa, he was very, very angry. And for good reasons: not only was a grave injustice being perpetrated against him personally, but against his people more generally. Yet, at some point Mandela realised that nurturing his anger, and insisting in thinking of his political opponents as sub-human monsters, would lead nowhere. He needed to overcome that destructive emotion, to reach out to the other side, to build trust, if not friendship. He befriended his own guard, and eventually his gamble paid off: he was able to oversee one of those peaceful transitions to a better society that are unfortunately very rare in history.

Interestingly, one of the pivotal moments in his transformation came when a fellow prisoner smuggled in and circulated among the inmates a copy of a book by yet another Stoic philosopher: the Meditations of Marcus Aurelius. Marcus thought that if people are doing wrong, what you need to do instead is to ‘teach them then, and show them without being angry’. Which is exactly what Mandela did so effectively.

So, here is my modern Stoic guide to anger management, inspired by Seneca’s advice:

Engage in preemptive meditation: think about what situations trigger your anger, and decide ahead of time how to deal with them.

Check anger as soon as you feel its symptoms. Don’t wait, or it will get out of control.

Associate with serene people, as much as possible; avoid irritable or angry ones. Moods are infective.

Play a musical instrument, or purposefully engage in whatever activity relaxes your mind. A relaxed mind does not get angry.

Seek environments with pleasing, not irritating, colours. Manipulating external circumstances actually has an effect on our moods.

Don’t engage in discussions when you are tired, you will be more prone to irritation, which can then escalate into anger.

Don’t start discussions when you are thirsty or hungry, for the same reason.

Deploy self-deprecating humour, our main weapon against the unpredictability of the Universe, and the predictable nastiness of some of our fellow human beings.

Practise cognitive distancing – what Seneca calls ‘delaying’ your response – by going for a walk, or retire to the bathroom, anything that will allow you a breather from a tense situation.

Change your body to change your mind: deliberately slow down your steps, lower the tone of your voice, impose on your body the demeanour of a calm person.

Above all, be charitable toward others as a path to good living. Seneca’s advice on anger has stood the test of time, and we would all do well to heed it.

No comments:

Post a Comment