This is actually the BIG project for all humanity that as we enter our true futures, that we all will be engaged in setting up and seeing through. The challenge though is to establish secure Refugio on continental lands.

Evgery island represnts a rat removal project before you try anything. Most certainly introduction of the passenger pigeon needs rat protection.

So it will not be quick but it will be ineviotable as we master the necessary husbandry. The wild is always in need of husbandry to avoid excessive dead zones. Think blow downs to see things halted for decades.

'Rewilding' Movement Aims to Restore Land to the Way It Was 11,000 Years Ago

Jan 20, 2017 12:52 PM ET

http://www.seeker.com/rewilding-movement-aims-to-restore-the-land-to-the-way-it-was-11000-ye-2203488102.html?sf52017151=1

What was Earth like before humans dominated the planet? Ecologists are creating pristine spaces to find out.

Rob Brewster has worked in environmental management for nearly two decades. Over the years, on Friday evenings, he would sit with colleagues and assess the week's work. Brewster said he repeatedly heard stories about "apathetic public servants" and other people who felt, "too small to make a change, so I'm just going to enjoy my time on the planet and not care anymore."

Frustrated by this grim view for the future, Brewster decided to shake things up in his homeland of Australia. "It just became obvious that we have to change the message and say, 'No! I don't accept a worse environment,'" he said. "I'll only accept a healthier more biodiverse Australia, and I'm going to tell everyone about this better, more exciting future, and breed enthusiasm for creating a rich, more interesting environment that we inevitably share with our wildlife. That led us to create Rewilding Australia."

The organization is one of several efforts across the globe to restore areas of land to an uncultivated state. The process sometimes involves the reintroduction of species that have seen steep population declines, or been driven out or completely exterminated.

In Australia, there have been notable successes with two meat-loving marsupials, the Tasmanian devil and the quoll. Tasmanian Devil Facial Tumor Disease has devastated wild populations of these animals over the past 20 years. Captive breeding, island introductions and population augmentation programs that return healthy devils to the wild "mean that the future is looking brighter for the species," Brewster said.

Quoll. Credit: Wikimedia CommonsThe flagship project of Rewilding Australia is the reintroduction of eastern quolls to the mainland, and it's gaining pace. Feral cats and foxes have contributed to the decline of this and other smaller animals across Australia in recent years. But with the assistance of the local government, funding partners and more, Brewster said, the species has been successfully reintroduced.

Work to strengthen populations of existing endangered animals is something that few environmentalists would question. After all, as Phil Seddon, a professor of zoology at the University of Otago, told Seeker, reintroductions "have taken place for decades, conservation introductions are growing in number, and the idea of rewilding has already taken hold in Europe."

"De-ex," Seddon said, "is the new frontier."

Giant Cattle, Woolly Mammoths

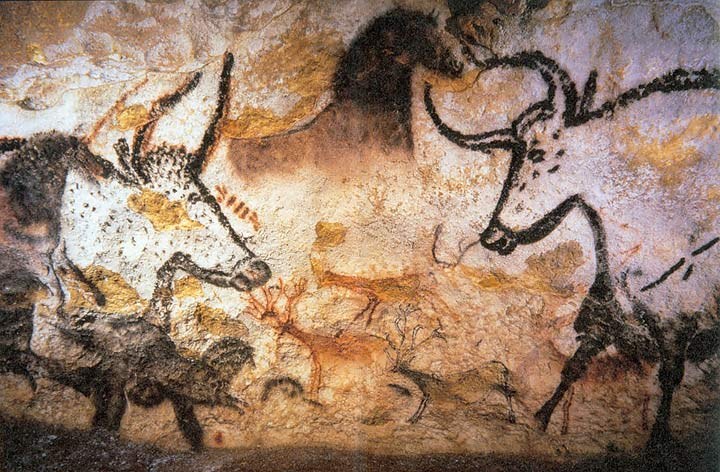

A de-extinction project is currently underway in Europe to bring back giant wild cattle, known as aurochs, which died out in 1627. Standing up to 6 feet tall and weighing 1,500–3,000 pounds, aurochs were the ancestors of today's domestic cattle.

Aurochs depicted in a cave painting at Lascaux, France. Credit: Wikimedia CommonsRewilding

Europe and the Taurus Foundation have established five breeding sites for the Tauros program, which is primarily crossbreeding Iberian and Podolian breeds of cattle in order to achieve mammals with auroch-like properties. The resulting cattle, called Tauros, are now located in Portugal, Spain, Croatia, Romania and the Netherlands.

"In the near and more distant future, herds of Tauros will live as wild cattle and will contribute to the sustainable conservation of Europe's open landscapes and biodiversity," Ronald Goderie of the foundation and his colleagues wrote in a recent report.

Progress is also being made to bring back the woolly mammoth, which disappeared from its primary range around 10,000 years ago (with isolated populations surviving on two islands until 5,600–4,000 years ago), and the passenger pigeon, which died out around 1900.

The Harvard Woolly Mammoth Revival team, led by George Church, is currently using genetic engineering to copy and paste DNA from the mammoth genome into living elephant cell cultures. Mutations for mammoth blood, fat and hair development have already been engineered into the elephant cell lines utilizing the genetic editing technology known as CRISPR.

Much work remains, but "the ultimate goal of woolly mammoth revival is to produce new mammoths that are capable of repopulating the vast tracts of tundra and boreal forest in Eurasia and North America," according to the project. "The goal is not to make perfect copies of extinct woolly mammoths, but to focus on the mammoth adaptations needed for Asian elephants to live in the cold climate of the tundra."

Church and his team explain that there are three primary reasons for bringing back the woolly mammoth: The work offers clues to large mammal conservation; ancient DNA holds secrets that affect modern biology and medicine; and mammoths are thought to have maintained grasslands, which could insulate permafrost and sequester climate change-associated atmospheric carbon.

Debate Over Conservation Benchmarks

The Harvard project and others have looked to the pre-Pleistocene era, more than 11,700 years ago, for inspiration. At that time, mammoths existed in habitats with abundant herds of antelope, deer, cattle, horses and other animals before climate change, human impacts or some combination of the two led to the herds vanishing.

Dutch forest ecologist Frans Vera, however, has indicated that the pre-Neolithic period (around 8,000 to 5000 years ago) could serve as a benchmark for current conservation, given that parts of Europe were likely in a relatively pristine or natural state then.

Kathy Hodder of Bournemouth University led an exploration of Vera's proposal, attempting to determine if the pre-Neolithic period could serve as a template for modern nature conservation. Hodder and her team wrote: "It would seem reasonable to assume that no one really believes that past landscapes can be restored exactly, but that invaluable lessons may be learned by looking back, and that we can strive towards, but never reach, a future natural state.The outcomes of such efforts are by definition uncertain and unpredictable, and none of us will live long enough to see the outcome of these attempts."

Benefits Could Exceed Risks, So Long as There's an Easy Out

Seddon warned that there are risks in moving plants and animals around.

"A reintroduction involves putting organisms back where they used to be, so in some ways is the most conservative and least risky type of conservation translocation," he said. "However, when we start moving species outside their indigenous range, to protect them from threats or to perform certain ecological functions, then there is a much higher level of uncertainty — uncertainty over whether it will work, or whether there might be unforeseen consequences.

"The potential for 'even worse problems' is certainly there and that is why no translocation should be undertaken lightly and importantly there should be an 'exit strategy' — can you reverse it by taking the released plants or animals back out of the release site if there are problems?"

Brewster admitted that, with the human population at over 7 billion and rising, defining nature is now is complicated, given that our species has influenced virtually every ecosystem on the planet. Australian biologist Tim Low even coined the term "new nature," to describe today's environment.

Brewster remains undaunted by the challenges. He he still derives joy and wonderment from "seeing a Tasmanian devil slowly moving through a forest, or looking under a rock ledge to see a quoll looking back at you.

"While rewilding looks back in time to learn about those lost ecosystem connections we can restore, we have to work with the environmental constraints we now have in our environment — invasive species, people seeking resources, farms, cities, roads and a warming climate — and we need to help to manage ecosystems to maintain ecosystem function and connections that are so important for biodiversity to flourish."

Photo: Tasmanian devil. Credit Thinkstock

No comments:

Post a Comment