In the meantime we are excited by the discoveries of Flores Island and overlook the fact that a similarly sized population lives in Northern Australia and is alive and well thank you.

We live in the great age on inter human hybridization, which is very much to our general benefit and is also ongoing. Unique sub populations are naturally absorbed into the larger commons over a rather short time period.

We are told of a simple atrocity, yet hundreds live on. The potential for thousands living on in the forest is also there. Probably not but active interfacing is certainly likely. .

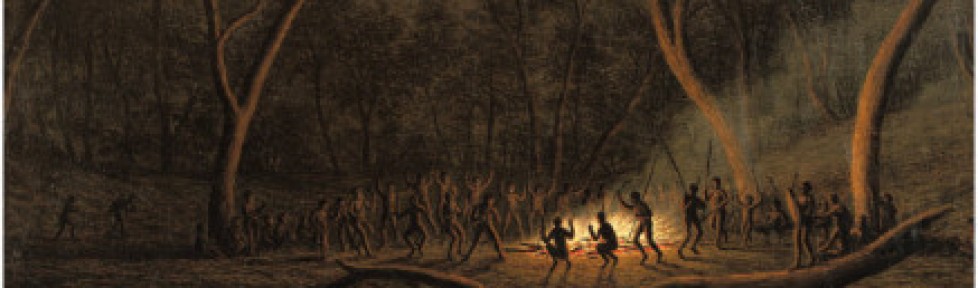

The Little People of Kuranda

Friday, 17 June 2016

http://nexusilluminati.blogspot.ca/2016/06/the-little-people-of-kuranda.html

Today’s post is about a little known tribe of Little People that still exists today in Far North Queensland, Australia.

In the 1400’s and 1500’s, Dutch and Portuguese sailors sighting the Western Australian coastline noted “tall natives in warfare chasing and killing hordes of “little” native peoples”.

Yet, since then, the Australian pygmies have been totally obliterated from public memory.

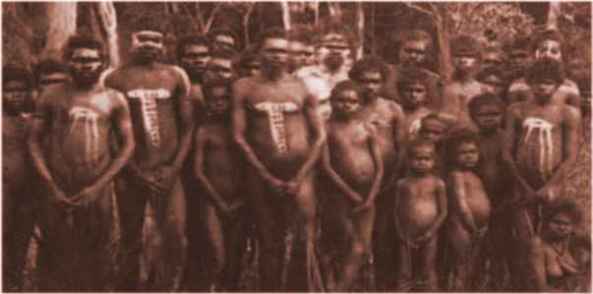

The Encyclopedia of Aboriginal Australia (1994), published by the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, today does its best to disguise these people. It lists some of their tribes, including the Djabuganjdji, Mbarbaram (Barbaram) and Yidinjdji (Indindji), but does not mention a word about their stature. Only its entry “Rainforest Region” records the existence of “small, curly-haired people with languages which have distinctive features”, but the accompanying photograph of Yidinjdji tribesmen taken in 1893 does not give any scale or point of comparison to show that these adult males were only about 140 centimeters (four feet six inches) tall.

Joseph Birdsell, height 186 centimetres (six feet one inch), with twenty-four-year-old male of the Kongkandji tribe, height 140 centimetres (four feet six inches). The photograph was taken at Mona Mona Mission, near Kuranda, North Queensland, in 1938.

The Little People are still alive and well in the forests around Kuranda, which any Djabagay or Bulawai will confirm, their survival due to the fact that they cannot be seen by the whitefella.

Kuranda Primary School has the lowest average height amongst Original peoples in any school in the whole of Australia.

Watch this video from 23m15s for more evidence: : https://www.youtube.com/watch?t=1242&v=fisLWLggrcM

A June 1861 report describes the first colonial encounter with this remote tribe :

“… their strange speech came forward in very soft tones… almost a whisper… a most unusual observance… took to conversation in (known) tongues… they commenced to converse with each other not using language… communication was in hand gestures and tongue “clicking”… tried to communicate with their hand signals… could not take to their unclear meanings… spoke again in (Mary River) Ka’bi language… response came forward finally… learnt that the ancient ones of Dha’muri… taught their ancestors the sign language… found all of this most unusual… able to record that these people were not in size a large clan group only numbering near one hundred and were scattered in the forests… they gave signals to follow them to an area on the shoreline… took to amazement on witnessing a stone structure of columns and an archway of great age… a state of collapse near four ceremonial rings… stonework lay on the ground and in the waters… the name Dha’muri was mentioned… took to quick artistry of the scene and the writings on the pinnacles… made contact with the remaining clan at a place called War’pbunga… the Place of the Frogs…”

What eventually happened to the Cairns rainforest people?

The following (edited) report of June 1864 tells of the “little people’s” shocking demise:

“… awoke to the sound of much gunfire… came across a most despicable act of humanity… as if a great war had been fought… bloodied native corpses covering the grounds and in the stream waters… recognised these were the Dhi’lumi little peoples of … previous acquaintances… peppered with gunshot… his woman bearing signs of harsh raping… throat slashed… their daughter and son… killed part decapitated and hanging over a tree branch – the son less his manly wares… slaughter appears to have been immediate without warning… cooking fires were still burning… their shantys and possessions lay strewn about the ground… utter disgust that these shy, ancient and good people had been shot to their deaths… Who could have done such an evil and dastardly deed?”

“… viewed the bloody scene with much contempt… none had survived. This last group of the Dhi’lumi were all quite dead… 43 members of the clan as I had counted… five old men and eleven other males were shot… their scrotums cut away… five old women and six young women… staked, tied down and then brutalised… signs of virginity lost or rampant bodily attacked then shot in the head… found six young boys and six young girls of the near ages of 9 to 12 years… brutalised in a most cruel manner similar to their mothers… blood seeping from their front and rear orifices. Bastards! Bastards! … The last were found in the tall water bushes of the stream… 4 young babies (2 boys and 2 girls)… their small throats cut open to dye the waters and left to die… lone act with the small children emptied my churning stomach of its full contents. What manner of animal could do such atrocities to another human being?”

The settlement at Yarrabah still exists at Cape Grafton. After 1897 it was not confined to the local people but accommodated Aborigines from all over North Queensland. The missionaries deliberately disrupted traditional tribal betrothals so that a fair amount of inter-marriage took place. It ceased to be a mission in 1960 when it was taken over by the Queensland Government. In 1986 it became a self-governing Aboriginal community but by then a large number of residents had left.

Mona Mona mission continued until 1962 when it was closed down. Its residents were dispersed to other Aboriginal reserves and into the general population. Some former residents now living at Kuranda want the original mission land returned to them.

Today, there are 14,700 Aboriginal people living in the Cairns region. We presume a good proportion of them must be descendants of the original Kongkandji, Barbaram, Indindji and Djabuganjdji tribes.

The first extended contact between Europeans and Australian pygmies occurred in the 1890s at Yarrabah, an Anglican church mission to Aborigines established in 1892 at Cape Grafton, just south of Cairns. The three main tribes in the region were the Kongkandji (Gungganydji), Indindji and Barbaram, whose territories covered, respectively, the coastal area around Cape Grafton, the eastern slopes of the Atherton Tableland from Lake Barrine south to Gordonvale, and the Great Dividing Range behind Cairns. All of them shared the same very short physical stature, as well as similar languages and culture.

In the mission’s first five years, about 150 Kongkandji periodically visited to receive rations but only a small number remained there permanently. After the Queensland Government passed its Aboriginal Protection Act in 1897, which forced Aborigines to be legally confined to reserves and missions, Yarrabah grew to a settlement of 150 residents drawn not only from the three local tribes but also from people all over North Queensland who bore no physical or cultural resemblance to the Cape Grafton Aborigines. Outside the mission, however, no one paid these people any special attention until an Adelaide researcher came across them in the late 1930s.

In 1938, Norman Tindale, an entomologist and anthropologist at the South Australian Museum, was going through a package of old photographs of Aborigines from the Warburton Mission sent him by a friend in Western Australia. One of the photographs of a group of men and women was labeled “Aborigines of north-west Australia”. The Warburton Mission was on the edge of the Gibson Desert, but the background of the photograph was clearly tropical jungle. It showed a wet weather hut thatched with what Tindale, a keen naturalist, recognized as the broad leaves of the wild banana tree. He could also tell that, if these were banana leaves, the people by comparison were very small. He made some enquiries and soon found that the only remaining stands of this plant were in the tropical rainforests on the eastern slopes of the Atherton Tableland in North Queensland.

At the time, Tindale and the American academic, Joseph Birdsell, were engaged in the most extensive project ever mounted in Australian physical anthropology to measure a large sample of Aborigines according to their weight, stature and a number of other bodily characteristics. They found the prospect of discovering a group in the Queensland rainforests so at variance with the norm, irresistible.

They also knew that, since the nineteenth century, there had been a number of theories about the origins of the Aborigines and the migration of ancient peoples to the Australian continent. In 1927, in his book, Environment and Race, the controversial Sydney geographer, Griffith Taylor, had speculated that several waves of Aboriginal migrants had swept before them an even older “Negrito” race. Maybe these rainforest people held the key to the story.

As soon as they could, Tindale and Birdsell drove from Adelaide to Cairns in search of the people in the photograph. They eventually found six hundred of them from twelve different tribal groups living on and around two missions, Yarrabah at Cape Grafton and Mona Mona at Kuranda on the Atherton Tableland. Some of them had only come in from the rainforest within the previous six years and spoke only their native tongue. They said there was still one family living a completely nomadic, hunter-gatherer life in the mountains behind Cardwell.

Tindale and Birdsell examined and measured 52 adults and children at Cape Grafton and 95 at Kuranda. Most adult males were between 140 and 150 centimeters tall (four feet six inches to five feet). The women were shorter by 15 to 30 centimeters (six to twelve inches). Tindale and Birdsell concluded they were not just small but were radically unlike any other Aborigines in Australia. They named them Barrineans, after nearby Lake Barrine. Tindale later said:

Their small size, tightly curled hair, child-like faces, peculiarities in their tooth dimensions and their blood groupings showed that they were different from other Australian Aborigines and had a strong strain of Negrito in them. Their faces bore unmistakable resemblances to those of the now extinct Tasmanians, as shown by photographs and plaster casts of the last of those people.

By 1963, when Tindale wrote these words in his book, Aboriginal Australians, the Barrinean pygmies were no longer an unknown people consigned to the oblivion of distant mission stations. Nor were they mere physical curiosities. They had become the centerpiece of what was then a widely influential explanation of the origins of human settlement on this continent.

No comments:

Post a Comment