It took a thousand years for the name to travel across Asia. That tells us how fast real knowledge traveled during the stone age. and we neded to know that because it was important.

Nothing really stood still or was blocked from transmission if it was important.

all this means is that silk provided an independent currency for global trade forever and could even act as a natural mirror for price comparisons.

A silken web

From its mythic beginnings in a Chinese garden, the story of silk is a window into how weaving has shaped human history

Some say that history begins with writing; we say that history begins with clothing. In the beginning, there was clothing made from skins that early humans removed from animals, processed, and then tailored to fit the human body; this technique is still used in the Arctic. Next came textiles. The first weavers would weave textiles in the shape of animal hides or raise the nap of the fabric’s surface to mimic the appearance of fur, making the fabric warmer and more comfortable.

The shift from skin clothing to textiles is recorded in our earliest literature, such as in the Babylonian Epic of Gilgamesh, where Enkidu, a wild man living on the Mesopotamian steppe, is transformed into a civilised being by the priestess Shamhat through sex, food and clothing. Judaism, Christianity and Islam all begin their accounts of their origins with a dressing scene. A naked Adam and Eve, eating from the forbidden tree, must flee the Garden of Eden. They clothe themselves and undertake a new way of life based on agriculture and animal husbandry. The earliest textile imprints in clay are some 30,000 years old, much older than agriculture, pottery or metallurgy.

Persian Carpet Dealer on the Street (1888) by Osman Hamdi Bey (1842-1910). Nationalgalerie der Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Berlin. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons

In the 21st century, the Silk Roads have re-emerged as the catch-all name for a highly politicised infrastructure project across Asia. The name Silk Roads comes from the origin and spread of sericulture – the practice of making silk fibres – in which Chinese women have played a special role. The discovery of silk fibres is attributed to the Empress Ling Shih, known as Lei Zhu. Legend says a silk cocoon fell into her cup and began to unravel in the hot tea water while she sat under a mulberry tree. Another legend tells that it was a Chinese princess who brought sericulture out of China to the Kingdom of Khotan by hiding silkworm eggs in her hair when she was sent to marry the Khotanese king.

In Modern Chinese, sī (絲, ‘silk, thread, string’) is commonly reconstructed as Middle Chinese *si. Linguists believe that the word journied via nomadic tribes in western China who also adapted the Mongolian word sirkeg (‘silk fabric’) and the Manchu sirge or sirhe (‘silk thread, silk floss from a cocoon’). The Greek noun sērikón and Latin sēricum come from the same Chinese root. The English word silk, Old Norse silki and Scandinavian silke – transferred into Finnish and Karelian as silkki, Lithuanian šilkas, and Old Russian šĭlkŭ – all have the same origin in Chinese. It took approximately one millennium for the word ‘silk’ to travel from China to northern Europe via Central Asia and Iran: 10,000 kilometres in 1,000 years.

In ancient Asia, silk was valuable and coveted, even by the powerful. It is said that in the year 1 BCE, China paid off invaders from the north with 30,000 bolts of silk, 7,680 kg of silk floss and 370 pieces of clothing. Among the less powerful, textiles possessed even greater value. We know from 3rd- and 4th-century Kroraina kingdom legal documents (from Chinese Turkistan, present-day Xinjiang province) that the theft of ‘two jackets’ could occasion a crime and that ‘two belts’ were significant enough to appear in wills.

Silk became the symbol of an extravagance and decadence

The classical Greek and Roman world thought of India as the site of great textiles and garments. The Romans marvelled at Indian saffron (Crocus indicus), a precious spice and dye plant yielding a bright yellow. Indigo was among the most valuable commodities traded from Asia. Diocletian’s Edict of Maximum Prices of 301 CE tells us that one Roman pound of raw silk cost the same as nine years’ wages of a smith.

In Rome, silk became the symbol of an extravagance and decadence that some saw as corrupt and anti-Roman. Cleopatra was also said to wear quite inappropriate clothing of Chinese origin, revealing her breasts and therefore also her vanity, and indicating loose morals and greed. The Roman emperor Elagabalus was described contemptuously by his contemporary Herodian, who wrote that the ruler refused to wear traditional Roman clothes because they were made of inferior textiles. Only silk ‘met with his approval’.

The Roman poet Horace dismissed women who wore silk, arguing that its lightness meant that ‘you may see her, almost as if naked … you may measure her whole form with your eye.’

The technology behind silk had long been a historical puzzle. The recent archaeological discovery of a 2nd-century BCE Han dynasty burial chamber of a woman in Chengdu has now solved it. Her grave contained a miniature weaving workshop with wooden models of doll-sized weavers operating pattern looms with an integrated multi-shaft mechanism and a treadle and pedal to power the loom. Europeans wouldn’t devise the treadle loom, which enhances power, precision and efficiency, for another millennium.

This technology, known as weft-faced compound tabby, also emerged in the border city of Dura-Europos in Syria and in Masada in Israel, dating to the 70s CE. We can, however, be confident that the technique known as taqueté was first woven with wool fibre in the Levant. From there, it spread east, and the Persians and others turned it into a weft-faced compound twill called samite. Samites became the most expensive and prestigious commodity on the western Silk Roads right up until the Arab conquests. They were highly valued international commodities, traded all the way to Scandinavia.

In Norway in 834 CE, two women were buried in the large Oseberg Viking ship, loaded with silk textiles, including more than 110 silk samite pieces cut into narrow, decorative strips. Most of the Oseberg silk strips are of Central Asian origin and they were probably several generations old when they were buried. The old Norse sagas speak of exquisite fabrics that were perhaps samites, even calling them guðvefr, literally ‘God-woven’.

These samite strips could have come to Scandinavia via close contact with the Rus communities settled along the Russian rivers, who could negotiate favourable conditions of trade with Byzantium. We know from historical sources that if a Rus merchant lost a slave in Greek territory, he would be entitled to compensation in the form of two pieces of silk. However, Byzantia also set a maximum purchase allowance for the Rus, and the maximum price for silk was 50 bezants. These silks that the Rus were trading in Byzantium, and then again with the Scandinavians, came from the Syrian cities of Antioch, Aleppo and Damascus.

Most early medieval silks in Europe are Byzantine, not Chinese. The Scandinavians also exported fur products to Asia that fuelled luxury consumption in Byzantium and eastwards, including coats, but also trimmings for hats and boots, and hems for kaftans and collars. The combination of fur and silk remained popular in prestige clothing to the Renaissance kings of Europe, and still exists in royal ermine robes.

Under the Muslim dynasties of the Umayyads (661-750), the Abbasids (750-1258), the Ilkhanids (1256-1335) and the Mamluks (1250-1517), diplomatic clothing gifts evolved into robes of honour. In Arabic, these are called khilʿa or tashrīf, and they are precious garments that a ruler would bestow upon his elites. They would then wear them to show loyalty. Silk gift-giving worked in both directions, it seems, and a caliph might receive hundreds of garments from one of his subjects.

A huge textile industry, private as well as royal, flourished in Baghdad in the 9th to 10th centuries, employing at least 4,000 people in silk and cotton manufacturing alone. Precious dyes, such as kermes from Armenia, offered opportunities for exclusive designs of bright-red fabric. Early Islamic scholars praise Central Asia not only for its silk but also for its wool, linen, fur and especially fine cotton. The 10th century also saw the spread of Islam, and the advance of trade networks lead to a renaissance in West African weaving and textile production.

The Rules and Regulations of the Abbasid Court state that, in the year 977 CE, the wealthy Adud al-Dawla sent the caliph gifts of 500 garments in a full range of qualities, from the finest to the coarsest – an excellent example of ‘silken diplomacy’. The Abbasid dynasty invested in palace textile workshops producing sophisticated patterns and techniques, such as the renowned tirāz. Originally a Persian loan-word, the term tirāz eventually became used for exquisite decorated or embroidered fabrics with in-woven inscriptions of the name of the ruler or praising Allah.

The silk tapestry roundel unites symbolic and aesthetic concepts from both the Islamic and Chinese realms

The purpose of tirāz textiles, at least to begin with, may have been a form of tax or tribute that was paid by provinces in Central Asia to honour new rulers when they took power. The term also came to be the name for a workshop where such exquisite fabrics with inscriptions were produced. The author Ibn Khaldūn, who wrote in the 14th century, dedicated a whole chapter to tirāz textiles in his book Muqaddimah:

Royal garments are embroidered with such a tirāz, in order to increase the prestige of the ruler or the person of lower rank who wears such a garment, or in order to increase the prestige of those whom the ruler distinguishes by bestowing upon them his own garment …

A 14th-century silk and metal-thread slit tapestry roundel. At its centre, an elegant ruler is seated on his throne, clad in a blue and gold robe or kaftan girded by a golden belt. He has a beard and a Persian-style crown, and is flanked by two seated noblemen, both wearing kaftans; on the right side is a Mongol prince or general, under whose foot is a blue tortoise, a typical Chinese symbol of longevity and endurance. Behind the throned ruler stand two guards wearing the same helmet-like hats. The medallion is decorated with an outer band of good wishes woven in Arabic golden letters, and inner bands of animals and imaginary creatures. Photo by Pernille Klemp, courtesy of David’s Collection, Copenhagen/Wikimedia Commons

The Abbasid rule ended in 1258 when Baghdad was conquered by the Mongols under the command of Hulegu, a grandson of Chinggis Khan. Hulegu took the title of Il-Khan to signal that he was subordinate to the Great Mongol Khans of China. One of his successors is portrayed in a silk tapestry roundel, uniting symbolic and aesthetic concepts from both the Islamic and Chinese realms (see image above). The depicted figures – Mongols, Persians and Arabs – manifest the union of ethnic and political groups in an idealised image of the Pax Mongolica. The technical features of this tapestry, made using a gold thread with a cotton core, suggest it may have been made in a cotton-growing region yet woven by Chinese weavers. The Mongols are famous for many things; it is less well known that they were great patrons of arts, crafts and textiles. The Ilkhanid dynasty ruled for some generations until it collapsed around 1335.

European imports of silks from China and Central Asia rose steadily in the Middle Ages. In 1099, after the capture of Jerusalem by the knights of the First Crusade, they increased again. The creation of Christian states in the Holy Land opened new trade routes, which facilitated the rise of the Italian city-states. The westward expansion of the Mongol Empire under Chinggis Khan and his successors also helped augment the power of these Italian trading centres. Great quantities of raw silk coming into Italy helped stimulate creative and technological progress in Europe, generating new techniques and patterns as well as new technologies. The lampas or woven fabrics especially fuelled innovation in patterning and the introduction of the treadle loom in medieval Europe.

While China was an important source of silk and other goods, South Asia had long been part of exchange networks linking the Indian Ocean world with the Gulf, Africa, Europe, and South-East and East Asia. Economic and political shocks from the 14th century led to surging prices for silk in European markets. The value of silk thread per ounce approached the price of gold.

In the early 15th century, the Chinese white mulberry (Morus alba) began to be successfully cultivated in Europe, in particular in Lombardy in Italy. We should not think of European silk cultivation and silk weaving only as a short business venture or a mere adjunct to Chinese or Asian dominance. Italy remained a leading global producer over several centuries, first of silk fabrics and then of silk threads, maintaining its position as the world’s second largest exporter of silk threads after China into the 1930s. To this day, Italian capacity and expertise in silk production survives.

The most famous legend tells of two monks who smuggled silkworm eggs to Europe

New silk institutions also emerged. In Valencia in Spain, between 1482 and 1533, the ‘Silk Exchange’ was erected to regulate and promote the city’s trade. It served as a financial centre, a courthouse for arbitration to solve commercial conflicts, and a prison for defaulting silk merchants.

The Hall of Columns in the Lonja de la Seda or ‘Silk Exchange’ in Valencia, built 1482-1533. A UNESCO World Heritage Site of cultural significance, its impressive pillars are shaped like z-spun threads. Photo Trevor Huxham/Flickr

Many legends arose around silk, primarily because of its value, with the technology of sericulture and silk production jealously guarded in China for millennia. Perhaps the most famous legend tells of two monks who smuggled silkworm eggs to Europe, thus breaking the production monopoly and revealing how silk was made.

In the second half of the 17th century, Paris became the centre of European textile production, design and technique. This included the emergence of a luxury shopping environment of boutiques and fashion houses. Fashion magazines such as Le Mercure galant reported on style and new trends from the royal court. The largest Parisian fashion houses, such as the Gaultier family business, supplied the wardrobes of the royal family and the nobility, and held shares in the French East India Company. King Louis XIV and his minister Jean-Baptiste Colbert invested in fashion and textile production as an important innovative sector to showcase France’s greatness.

Illegal imports of foreign textiles and luxury copies posed a challenge for French trade and domestic production. French consumers had a large desire for foreign textiles, and colourful, cheap fabrics flooded the market. Illicit products from Asia arrived via trading posts in the Philippines and Mexico, putting pressure on European fabrics and fashionable goods in terms of price and quality. King Louis XIV of France and his grandson, Philip V of Spain, sent Jean de Monségur, an industrial and commercial spy, on a mission to Mexico City to collect intelligence on the legal and illegal trade between India, China and Europe. His detailed intelligence report addressed the trade in textiles, clothing and fashion. With great concern, he wrote:

[T]he Chinese have got hold of our patterns and designs, which they have utilised well and can today produce quality goods, although not everything that comes from over there can match the European standard … The times are over when one could assume that the Chinese are clumsy, without talent or trade talent, or that their goods are not in demand.

Monségur also noted that Chinese silks were highly competitive because of their lower prices. In Mexico, even commoners wore Chinese silk clothing.

When the victorious Mongols conquered new land, they selected artisans, especially weavers, and saved their lives because they were crucial to the expanding empire’s needs and ambitions. These skilled craftspeople were then ordered to settle where the empire needed them, hence the large-scale forced movements of textile workers within the Mongol Empire.

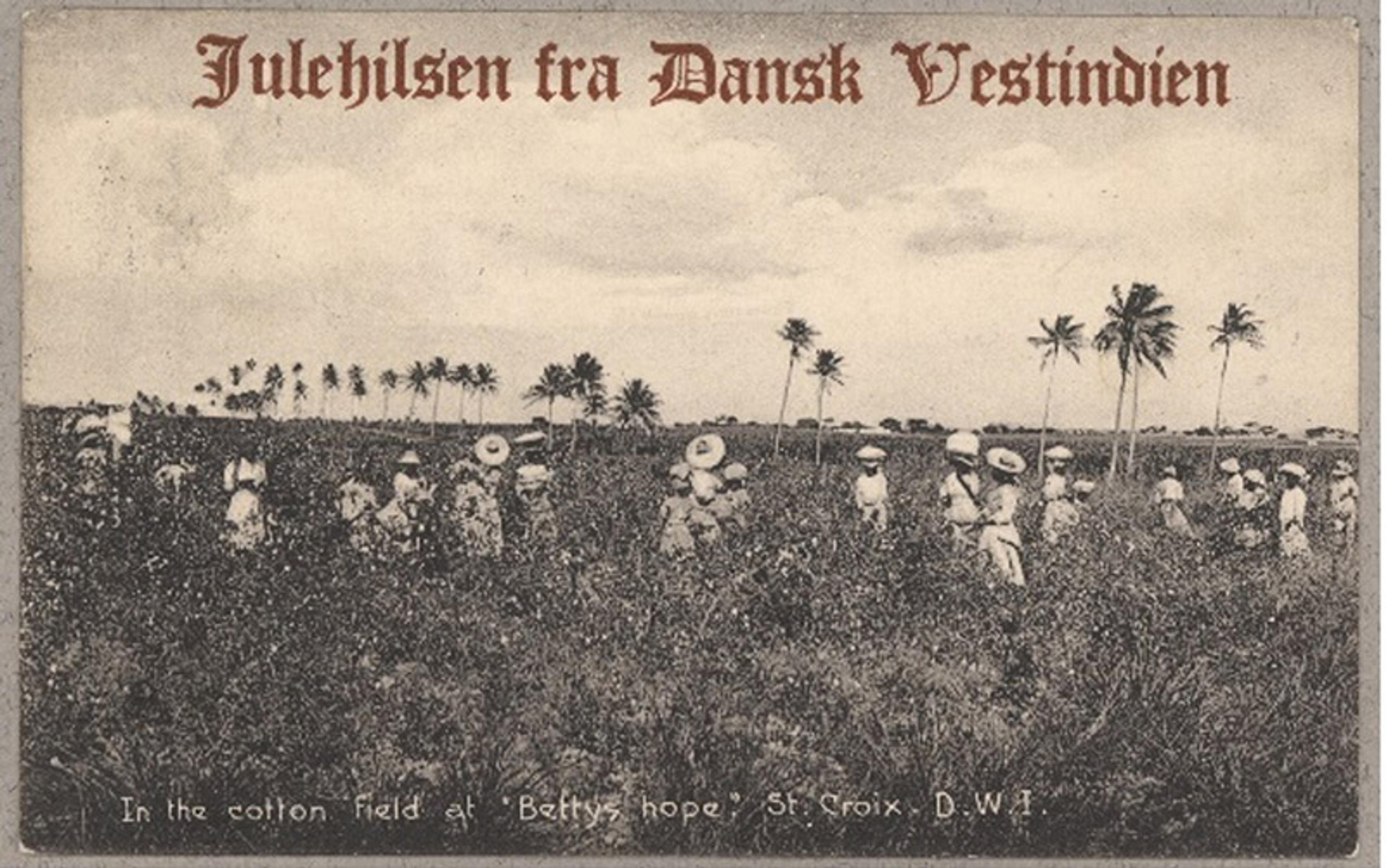

Beginning in the 15th century, the colonisation of the Americas brought about the largest forced textile labour movement in history. It forcibly displaced some 13 million people, transporting them from West Africa to the Caribbean and North America. Coerced labour was central in the establishment and development of a textile industry heavily dependent on cotton and indigo. Even today, cotton harvesting is very labour intensive: every year from September to October, millions of workers pick cotton in Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Pakistan, India, the United States and China. Cotton pledges have been signed by textile and fashion companies committed to banning forced labour in the cotton harvests, yet the massive need for labour and the low price of cotton are obstacles to these efforts.

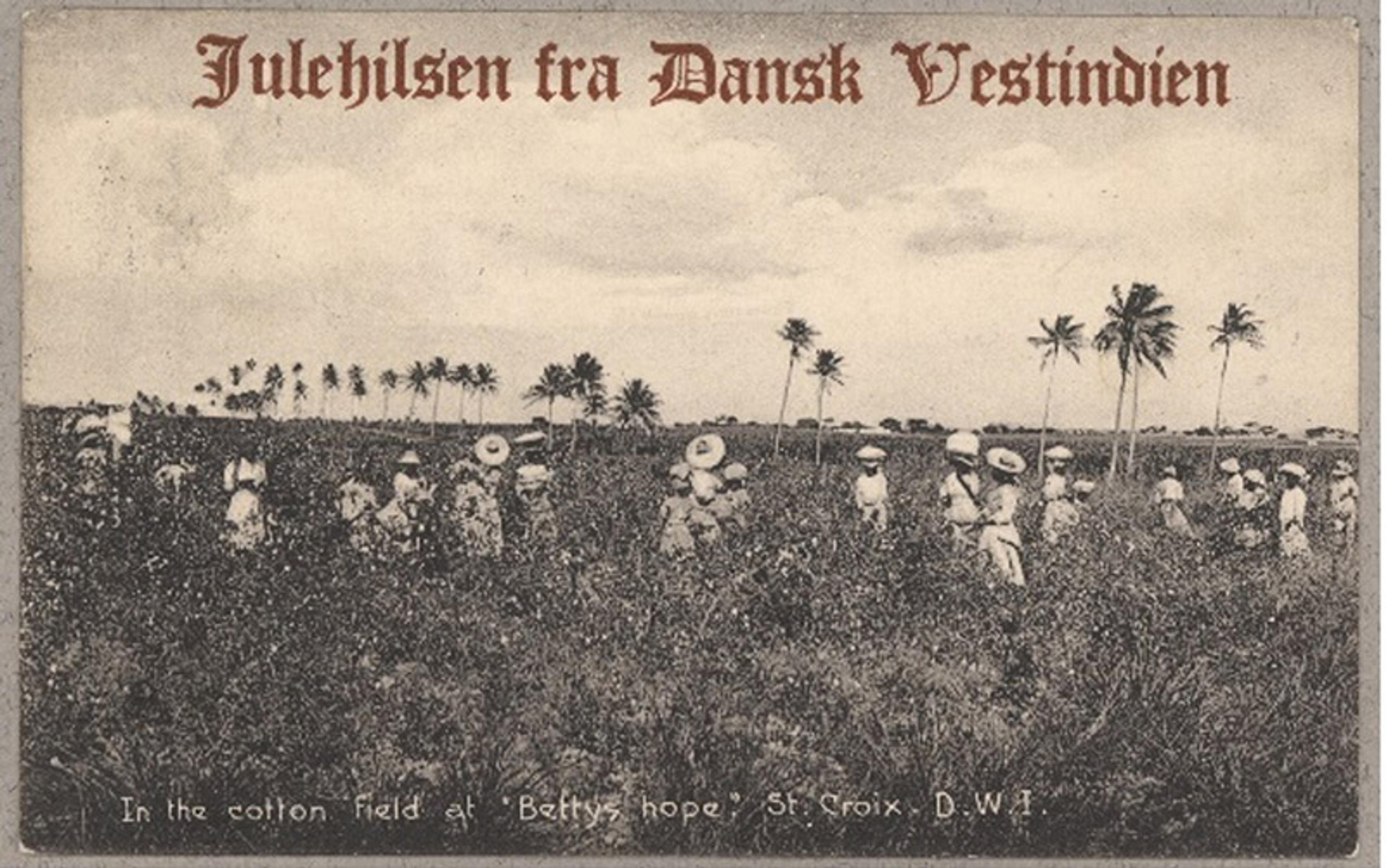

‘Christmas greetings from the Danish West Indies’: postcard from the cotton plantation Bettys Hope on the island of Saint Croix, a Danish colony until 1917 and today part of the US Virgin Islands. Courtesy of the Royal Danish Library, Copenhagen

Some 60 per cent of the 40 million people employed by the garment industry today are in the Asia-Pacific region. Working conditions and pay levels are often poor, in part because of the pressure to lower production costs. Implications for the health and safety of workers are often terrible: for example, when the poorly constructed Rana Plaza complex in Bangladesh collapsed in 2013, more than 1,100 garment workers lost their lives.

Everyone knows that clothing can symbolise power, legacy, glory, as well as ethnic or national identity and aspirations. In male power-dressing, we observe over time how clothing emphasises the ruler’s head, shoulders and torso, and a belt highlights bodily strength. Jewellery, weapons and other royal insignia serve as garnish. The choice of simple clothes, preferred by many Left-wing leaders, also projects meanings – and the source of their power.

The last emir of Bukhara, Alim Khan (1880-1944), dressed in a deep-blue silk robe. Photo by Sergei Prokudin-Gorskii. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons

Among the elite in many parts of Eurasia, Western dress practices became symbolic of a progressive mindset. In the late 17th century, Peter the Great imposed Western clothing on the civil administration of Russia. In Meiji-era Japan, the ruler and his family adopted full Western attire. The Japanese emperor would wear the sebiro, the Japanese term for ‘suit’ derived from Savile Row, the London street that was home to the finest gentlemen’s tailors.

Emperor Meiji in 1873, dressed in Western military parade uniform and with an admiral’s hat. Photo by Uchida Kuichi (内田九一) (1844-75). Albumen silver print from glass negative with applied colour. Courtesy of The Met Museum, New York

In the early 20th century, clothing became so accessible and cheap that rulers could demand that their subjects dress in a certain way and adapt their clothing to the ruler’s politics. They wanted the general population to mirror the rulers’ values, political beliefs and ambitions. For example, in 1925, the Greek dictator Theodoros Pangalos imposed a law stipulating that women’s dresses should not rise more than 30 cm from the ground. The same year, Ataturk’s Hat Law was passed in Turkey, another historical example of clothing regulations being used as a political instrument to orient, redress or change the mentality of an entire society. Wearing a Western hat and abandoning the traditional Ottoman and Islamic headgear of the turban and fez became a political act of adherence to the Kemalist republic. Men’s headgear became a potent symbol of ideology, and the ‘wrong’ hat was penalised with fines and, occasionally, even with capital punishment.

At the Yalta Conference in February 1945, Winston Churchill wears a civilian double-breasted wool coat, Franklin D Roosevelt, a civilian suit under a cape with tresses and a fur collar, and Stalin, a double-breasted Soviet uniform whose design mirrors both earlier Tsarist and 20th-century European uniforms. A Persian carpet from western Iran forms a connection between them all. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia

In the 20th century, military uniform design and cut followed those of the country’s allies and ambitions. We can see this in the military uniforms used across Eurasia during the Cold War, with a ‘communist’ style in countries allied with the Soviet Union or China, versus the ‘capitalist’ NATO styles used by the West’s allies.

Throughout the world, rulers have tried to control people by regulating their clothing

It is notable that textile metaphors gained currency to represent both the reign of the Cold War, with its ‘Iron Curtain’, and the period’s historic end in 1989, with the ‘Velvet Revolution’ in Czechoslovakia. The expressions play on both the softness of fabric (velvet) and its capacity to cover and conceal (curtain). In popular culture, it was denim and blue jeans that caught the imagination of young people in the East, as symbols of youth and of political and moral freedom. The name ‘denim’ comes from the French city of Nîmes in Occitanie, a major producer of blue dye from woad (Isatis tinctoria) and synonymous with workers’ blue cotton cloth. The word ‘jeans’ connects to the French name of Gênes and the Italian city of Genova, from where such coarse fabrics were exported.

Throughout history, and throughout the world, rulers have tried to control people by regulating their clothing. Regulations can be prescriptive or proscriptive, and carry gendered and social meanings and ramifications. Dress codes – from the military to school uniforms – indicate political and social alignment, to visually express unity, loyalty and adherence. Meanwhile, bans, prohibitions or censure of the dress practices of certain individuals or groups aim to exclude. When the Chinese emperor Zhu Yuanzhang, the founder of the Ming dynasty, took the throne in 1368, he banned the former regime’s style of clothing, branding it ‘barbaric’, and ordered a return to the clothing style of the Han dynasty.

Clothing regulations can be social or legal, and across Eurasia many have attempted to regulate how people dress to enforce an ideal, or to protect national production from foreign imports. Sumptuary laws (from Latin sumptus, meaning ‘expense’) could regulate both manufacturing and trade, as well as national moral economies that would influence consumption patterns and values. They represented social, gendered and racial hierarchies, and expressed them visually. Many regulated the use of jewellery and the practices surrounding feasts or funerals. The main objective was always directed at dress practices, with greater significance given to fabrics, fibres, weave and decoration than to cuts and tailoring. In Lima, Peru – in Spanish colonial America – sumptuary laws stipulated that women of African or mixed African and European descent were prohibited from wearing woollen cloth, silks or lace – though forbidden luxury fabrics often simply reappeared as cheaper copies, and trade labels were faked.

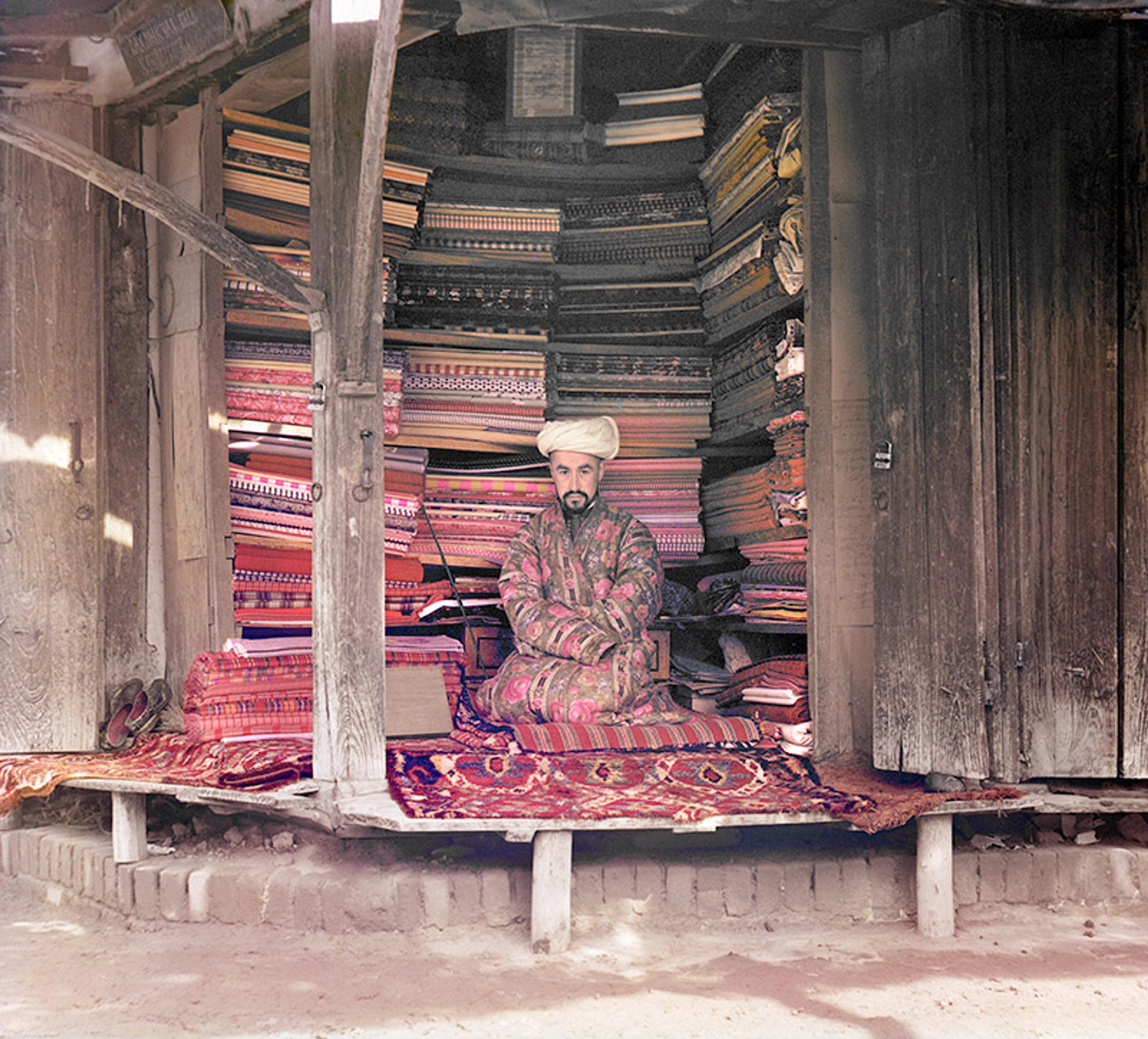

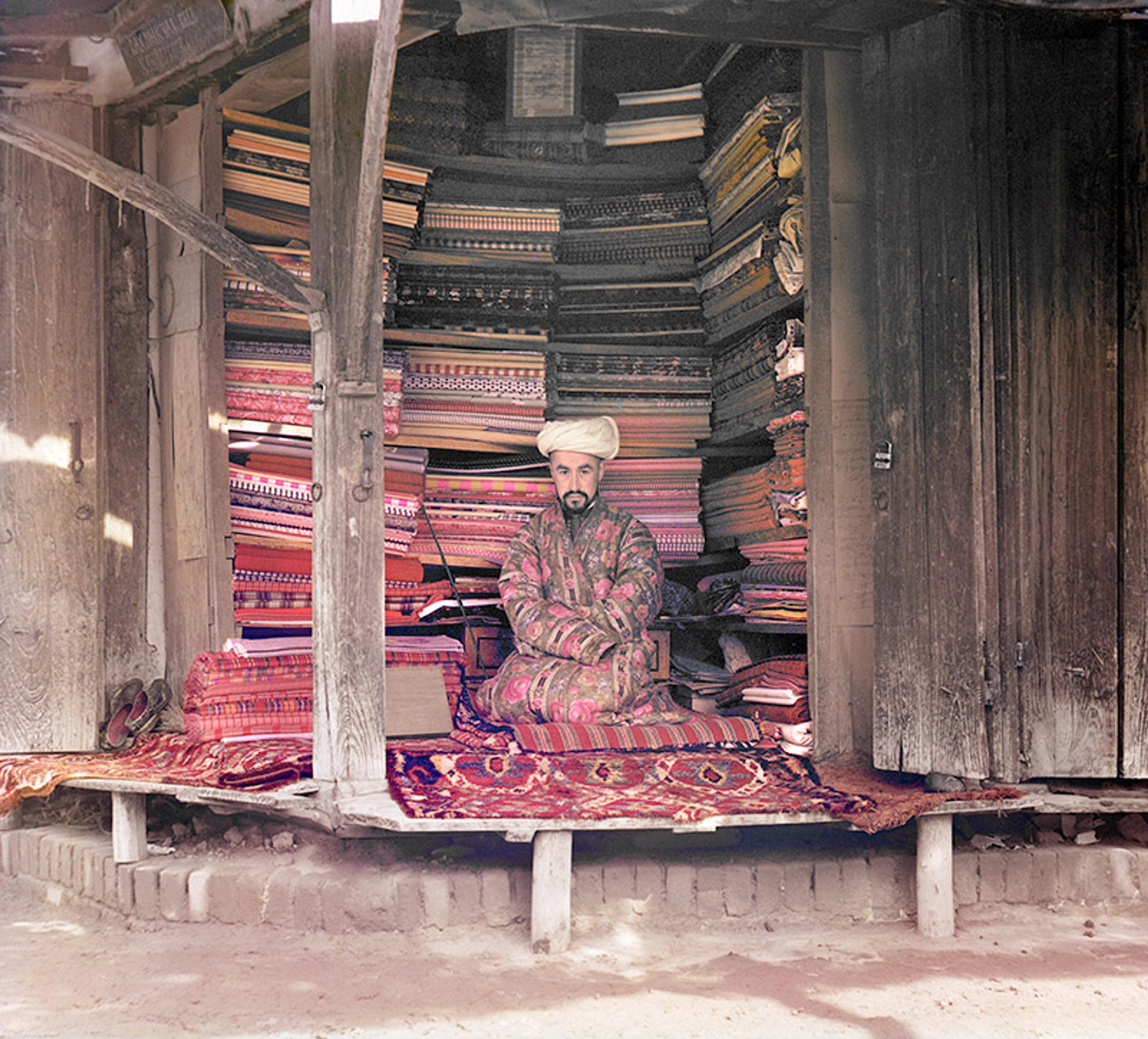

Fabric merchant in Samarkand, photographed between 1905 and 1915 by Sergei Prokudin-Gorskii. The merchant’s goods include striped silks, printed cotton, wool fabrics, and carpets. He wears a white turban and a silk kaftan adorned with Chinese-inspired floral motifs. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress

As globalisation intensified, it brought about technological breakthroughs in transport, communication and trade, through which dress has become more standardised, with many rich and diverse clothing cultures of the world diminished. Fortunately, the early 20th-century photographers Albert Kahn and Sergei Prokudin-Gorskii captured the clothing of many glorious local traditions of Central Asia. Today, we can see some of these local costumes only in tourist shows and museums.

Not surprisingly, we know much more about the textiles and clothing of the elite than about the attire of ordinary people on the Silk Roads. Archaeology can help. The Chehrābād tunic belonged to a salt-mine worker, perhaps trapped and killed when the mine collapsed around 400 CE. It was woven of monochrome cotton cut and sewn into a knee-length tunic with long sleeves. Perhaps the tailor knew the body size of the worker or about his hard toil in the salt mines, since gussets were inserted in the armpit areas and at the hips to provide him with greater freedom of movement. Weaving mistakes occur in many places, as if woven in a hurry, or maybe because this was, after all, a work outfit.

The history of textile production has always been linked to cheap labour. Shepherding, sericulture, and cotton and flax cultivation require many hands, time, constant tending, efficiency, and standardised tools and techniques. The mechanisation of the clothing industry and of textile production therefore produced dramatic change. Richard Arkwright’s inventions in the 18th century were put into industrial-scale production when the English entrepreneur introduced the spinning frame, adapted it to use waterpower, and patented a rotary carding engine. Arkwright’s achievement was to combine power, machinery, semi-skilled labour and a new raw material, cotton, to create mass-produced yarn.

European ladies wore fashionable, soft pashmina shawls with Iranian and Central Asian paisley patterns

The French city of Lyon took advantage of geographical advantages that helped it become the centre of a silk ‘tiger economy’. The hill of Croix-Rousse housed factories, with every street filled with the clamorous sounds of mechanical looms. With its 30,000 canuts (the nickname for Lyon’s silk workers), this industrious district turned Lyon into a major hub for textile production, especially silk-weaving, providing garments for the royal court and the nobility of Europe.

In the social world of the rising 18th- and 19th-century Western bourgeoisie, we find many products of the Silk Roads, both in textiles and designs. Ladies wore fashionable, soft pashmina shawls with Iranian and Central Asian paisley patterns – a style that had travelled from representing the bonds between Britain and its empire in Asia. Young and fashionable women in European royal families would inspire others to wear these colourful soft shawls as a new accessory. One of the most iconic ‘influencers’ was Empress Joséphine of France who integrated pashmina fabrics and paisley patterns into her wardrobe.

Portrait of Empress Joséphine (c1808-9) by Antoine-Jean Gros. Courtesy of the Musée Masséna, Nice/Wikipedia

Women of the Spanish Empire would wear the mantón de Manila, also known as the Spanish shawl, which takes its name from Manila in the Philippines, from where it was traded eastwards over the Pacific into the Spanish Empire of the Americas. Originally, it was a silk garment adorned with embroidery, and woven in Southern China, which was traded from the late 16th century via Manila and the Spanish-American colonies, then further into Europe via Spain.

Russian girls in a rural area 500 km north of Moscow, photographed by Sergei Prokudin-Gorskii in 1909. Industrially woven, colourful printed fabrics were accessible even in remote villages, and likely used, re-used, sewn and mended. At this time, dyes were chemically bonded and developed from the industrial competition between Germany, France and the UK in the race to patent new synthetic dyes. Courtesy of the Library of Congress

In An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (1776), Adam Smith wrote that trade was not only mutually beneficial to trade partners but to society as a whole. To illustrate his argument, he explored the competitive advantages of cloth compared with wheat. Textile production was to Smith a sign of economic dynamism. It was only following the French Revolution that clothing regulations were abolished and the nation’s citizens could dress as they wished: ‘Everyone is free to wear whatever clothing and accessories of his sex that he finds pleasing.’ However, the very same decree stipulated the obligation to visibly wear the cocarde knot of red, white and blue ribbons, emblematic of the French Revolution. It was implicitly asserted that clothing should be gender-appropriate and respect earlier dress regulations.

Two Germans with particular textile histories would revolutionise the political landscape of the 19th century. Friedrich Engels was the scion of the family behind the cotton company Baumwollspinnerei Ermen & Engels in western Germany, and he settled in the English city of Manchester, a leading centre for global cotton trade and manufacture. Karl Marx was greatly influenced by his close friend Engels and by the textile industry in particular. In Das Kapital (1867), Marx illustrated his arguments about the working classes by referring to the Lumpenproletariat – or the ‘proletariat of rags’ – and by using the example of an overcoat as an allegory for the measure of labour, resources, technology and the uneven rewards of capitalism.

In the 20th century, political transformations and new economic conditions and ideologies have negatively impacted artisanal weaving and other kinds of traditional crafts globally. Much intangible textile craft culture has been lost; new technologies have made handicrafts obsolete or very expensive; urbanisation has standardised fashion; and people no longer want to carry out what is seen as tedious textile work.

The word ‘text’ comes from Latin texere (‘to weave’), and a text – morphologically and etymologically – indicates a woven entity. We can therefore say that history starts not with writing but with clothing. Before history, there was nudity, at least in the Abrahamic tradition; clothing thus marks the beginning of history and society. The representation of nudity as part of a wild and pre-civilised life mirrors the European colonial perspective of the naked human as ‘wild’.

Across the world today, there are two main ways to dress: gendered into male and female, and stylistically into clothing tailored to fit the body, or draped/wrapped around it like the Roman toga or the Indian sari. Fitted clothing dominates globally, especially after the Second World War, with blue jeans and T-shirts now ubiquitous across all continents.

Today, a T-shirt on sale in any shop around the world is the result of a finely meshed web of global collaboration, trade and politics. From cotton fields in Texas or Turkmenistan, to spinning mills in China, garment factories in Southeast Asia, printers in the West, and second-hand clothing markets in Africa, a T-shirt travels thousands of kilometres around the world in its lifetime. On average, a Swede purchases nine T-shirts annually, and even if they are made to last 25 to 30 washes, consumers tend to discard them before. Greenpeace found that Europeans and North Americans, on average, hold on to their clothes for only three years. Some garments last only for one season, either because they fall out of fashion, or because the quality of the fabric, tailoring and stitching is so poor that the clothes simply fall apart.

This is the impact of fast fashion that has taken hold since the beginning of the 21st century: for millennia, clothing had always been expensive, worth repairing and maintaining, and made to last. Along with the acceleration of consumption came falling prices and an ever-narrowing margin for profit. The fast-fashion business model requires seamless global trade, inexpensive long-distance transportation, cheap flexible labour and plentiful natural resources. That equation is changing in a world that is warming and where trade barriers are coming up. The future of fabrics, textiles and clothing is bound up in the great themes of the present – and the future.

Reich Experimental Blood Test – Blood Disintegration

Reich Experimental Blood Test – Blood Disintegration

Reich Experimental Blood Test – Blood Disintegration

Reich Experimental Blood Test – Blood Disintegration

Scanning & Transmission Electron Microscopy Reveals Graphene Oxide in CoV-19 Vaccines

Scanning & Transmission Electron Microscopy Reveals Graphene Oxide in CoV-19 Vaccines

Scanning & Transmission Electron Microscopy Reveals Graphene Oxide in CoV-19 Vaccines

Scanning & Transmission Electron Microscopy Reveals Graphene Oxide in CoV-19 Vaccines

.jpg?width=3840&quality=75&format=auto)